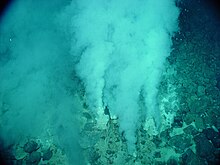

海底热泉(hydrothermal vent)亦作海底热液系统(Submarine Hydrothermal System)[1],是从海底喷出经由地热加热过的水及其裂缝喷发口。通常发现于火山活动频发、大陆板块移动的地区及海盆、热点附近。常见陆地类型为温泉、火山喷气孔和间歇泉。在海底常会形成海底烟柱,相对于同样深度的其他海底地区,海底热泉附近通常生物更为繁盛,它们倚靠分解热泉中流出的矿物质为食。化能合成细菌和古生菌形成了此处食物链的最底层,支持着多样化生物,包括巨型管虫、一些蛤蜊和节肢动物的生存。活跃的海底热泉还被认为存在于木星的卫星木卫二上,火星上可能还有古代的深海热泉。[2]

物理性质

编辑在中洋脊(例如东太平洋海隆和大西洋洋中脊)的海底热泉最为典型,此处大陆板块分离,并不断生成新的陆块。

相对于此深度通常大约2°C的环境水,海底热泉中喷出的水之温度可高达60至464°C。[3][4]同时由于此深度极高的液体静压力,海底热泉可能会成为超临界流体。其在218标准大气压下在纯水中的临界点是375 °C。在水下3,000米的深度,压力超过300标准大气压(海水密度超过淡水),因此在407 °C处成为超临界流体 ,拥有介于气体和液体之间的性质。[3][4]

姊妹峰(Sister Peak,4°48′S 12°22′W / 4.800°S 12.367°W,海拔-2996米)、虾场(Shrimp Farm)和墨菲斯托(Mephisto,4°48′S 12°23′W / 4.800°S 12.383°W,海拔-3047米)是三座拥有海底烟柱的深海热泉,坐落于阿森松岛附近的大西洋洋中脊,可能自2002年地震之后就开始活跃了。[3][4]其水体有相变发生。2008年,其中一个被测到水温超过464 °C。这种热力学条件已经超过了海水应有的临界点,这是第一个在洋中脊发现的岩浆-热水交互作用现象。[3][4]

最初的海底烟囱是由矿物质硬石膏沉积形成的。铜、铁、锌的硫化物矿物填塞其缝隙,减少孔洞。曾有记录显示海底烟囱可以快到每日增长30公分,到60米左右垮掉。[5][6]2007年4月的调查显示,斐济附近的海底热泉口有丰富的溶解铁。[7]

黑色和白色海底烟柱

编辑一些深海热泉会形成圆柱形的烟囱,其主要成分是热泉中的矿物。当超高温的热泉接触冰冷的海水时,矿物质沉淀析出变成烟囱的一部分,其中有些高达60米。[8]

黑色海底烟柱是一类极深的深海热泉,它们包含云雾状黑色物质,通常富含硫化物。黑色的海底烟柱首次在东太平洋海隆被发现于1977年,发现人是斯克里普斯海洋研究所的科学家,使用了伍兹霍尔海洋研究所的阿尔文号深潜器。现在黑色海底烟柱存在于大西洋和太平洋地区平均2100米深的水下。最北部的五个黑色烟柱被称为洛基城堡,[9]2008年,它们由卑尔根大学的科学家发现于格林兰岛和挪威之间北纬73°N的地点。这些黑色烟柱也发现于版块活动不那么活跃的地区。[10]

白色海底烟柱的颜色较偏酸性黑色海底烟柱更浅,富含钡、钙和硅元素会导致这种情况发生。它们的温度也较低,会持续形成柠檬酸循环。这里偏碱性水体和微观结构被认为是生命起源的温床。[11]

生物

编辑一般认为生物存活必须依靠阳光,但是许多深海生物能只依靠海地的沉积物为生。深海热泉为这些生物提供了栖身之所,海底热泉附近的水体富含矿物质及细菌。因此其附近通常会聚集著端足类和桡足类生物,更大型的生物还有鱼类、甲壳纲生物、管蠕虫和章鱼。

巨型管虫可长达2.4米,是深海热泉附近最重要的生物之一。它们没有嘴和消化道,依靠它们自身组织中的细菌生产的养分为生,每盎司管蠕虫组织中约有2850亿细菌。管蠕虫红色的羽状组织中含有血红蛋白。血红蛋白和硫化氢结合,并且转移到生活在管状蠕虫体内的细菌。细菌回报给管蠕虫含有碳化合物的养分。

其他生活在此地的奇特生物还有鳞足蜗牛,其非常奇特的足部附有铁化物和有机材料形成的起保护作用的鳞片。可在80 °C(176 °F)高温下存活的庞贝虫也发现于此地。

1993年,已知有超过100种腹足类生物聚集在深海热泉附近。[12]超过300个新物种在热液喷口被发现,[13]其中不乏在地理上分开的热液喷口地区被发现的“姐妹物种”。据信在北美洲板块覆盖原先的洋中脊时,东太平洋地区曾有一个单一的、生物地理独立的海底热泉生物群。[14]

在墨西哥海岸附近2,500米深处海底发现有光养细菌存在,在此深度并无阳光。这些绿菌门的细菌依靠黑色海底烟柱发出的微光来进行光合作用,这是世界首次发现不使用阳光进行光合作用的生物。[15]

探索

编辑1949年,一个深海调查项目探测到红海中心有不寻常的热水反应。后来发现这些热水来自于一个活跃的海床裂缝。[16]

1977年,一个由俄勒冈州立大学的杰克·科利斯领导的海洋地质学家团队在东太平洋海隆的加拉帕格斯裂谷海底热泉附近发现了一个化能合成生态系统。1979年,生物学家们再次回到这里利用伍兹霍尔海洋研究所的DSV Alvin号深海潜艇来探测裂谷,亲眼目睹了海底热泉生物群落。同年,彼得·朗斯代尔发表了第一篇关于海底热泉生物群落的科学论文。[17]

2005年,一家叫做Neptune Resources NL的海洋探测公司开始了对新西兰专属经济区克尔玛德克岛弧进行海底块状硫化物矿床探索。2007年4月,哥斯达黎加附近的美杜莎深海热泉田也开始了探索工作。[18]2010年,开曼海沟的皮卡尔德(Piccard site,18°33′N 81°43′W / 18.550°N 81.717°W,深度5,000米(16,000英尺))被伍兹霍尔海洋研究所和NASA喷气推进实验室的科学家发现。该深海热泉带长达110千米,也是世界上已知最深的深海热泉。[19]

2020年5月28日,中国科学院海洋研究所声称其旗下的“科学”号科考船在深海热液区首次观测到气态水存在[20]。

开发

编辑因为有丰富的海底块状硫化物矿床,深海热泉成为了海底开发的一个重要地区。澳大利亚昆士兰的伊萨山就是著名的开发地之一。[21]开发这些地区被认为极有经济价值。[22]

保护

编辑同时关于保护深海热泉的话题由来已久,在过去的20年中时常变成激烈话题。[25]实际上需要指出的是,目前为止对深海热泉造成了破坏的还包括那些探索此地的科学家们。[26][27]虽然有多次企图规范科学家们考察行为的国际公约,不过现在仍没有旨在保护深海热泉的国际公约。[28]

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ 博客來-海底熱液地質學. [2014-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-29).

- ^ Paine, M. Mars Explorers to Benefit from Australian Research. Space.com. 2001-05-15. (原始内容存档于2006-02-21) (英语).

- ^ 跳转到: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Haase, K. M.; et al.. Young volcanism and related hydrothermal activity at 5°S on the slow-spreading southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems. 2007, 8 (11): Q11002. Bibcode:2007GGG.....811002H. doi:10.1029/2006GC001509.

- ^ 跳转到: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Haase, K. M.; et al.. Fluid compositions and mineralogy of precipitates from Mid Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vents at 4°48'S. PANGAEA. 2009. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.727454.

- ^ Tivey, M. K. How to Build a Black Smoker Chimney: The Formation of Mineral Deposits At Mid-Ocean Ridges. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 1 December 1998 [2006-07-07]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-05).

- ^ 尼克·连恩. 生命的跃升:40亿年演化史上最重要的10个关键

- ^ Tracking Ocean Iron. Chemical & Engineering News. 2008, 86 (35): 62. doi:10.1021/cen-v086n003.p062.

- ^ Perkins, S. New type of hydrothermal vent looms large. Science News. 2001, 160 (2): 21. JSTOR 4012715. doi:10.2307/4012715.

- ^ Boiling Hot Water Found in Frigid Arctic Sea. LiveScience. 24 July 2008 [2008-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2011-01-01).

- ^ Scientists Break Record By Finding Northernmost Hydrothermal Vent Field. Science Daily. 24 July 2008 [2008-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-16).

- ^ Lane, N. Life Ascending: the 10 great inventions of evolution. Profile Books. 2010. ISBN 978-0393338669.

- ^ Sysoev, A. V.; Kantor, Yu. I. Two new species of Phymorhynchus (Gastropoda, Conoidea, Conidae) from the hydrothermal vents (PDF). Ruthenica. 1995, 5: 17–26 [2013-04-21]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-08-08).

- ^ Botos, S. Life on a hydrothermal vent. Hydrothermal Vent Communities. [2013-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2018-01-04).

- ^ Van Dover, C. L. Hot Topics: Biogeography of deep-sea hydrothermal vent faunas. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. [2013-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2012-04-04).

- ^ Beatty, J.T.; et al.. An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005, 102 (26): 9306–10. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9306B. PMC 1166624 . PMID 15967984. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503674102.

- ^ Degens, E. T. Hot Brines and Recent Heavy Metal Deposits in the Red Sea. Springer-Verlag. 1969.

- ^ Lonsdale, P. Clustering of suspension-feeding macrobenthos near abyssal hydrothermal vents at oceanic spreading centers. Deep Sea Research. 1977, 24 (9): 857. Bibcode:1977DSR....24..857L. doi:10.1016/0146-6291(77)90478-7.

- ^ New undersea vent suggests snake-headed mythology (新闻稿). EurekAlert!. 18 April 2007 [2007-04-18]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-24).

- ^ German, C. R.; et al.. Diverse styles of submarine venting on the ultraslow spreading Mid-Cayman Rise (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010, 107 (32): 14020–5 [2010-12-31]. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10714020G. PMC 2922602 . PMID 20660317. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009205107. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-03-03). 简明摘要 – SciGuru (11 October 2010).

- ^ 中国科学院海洋研究所 首次在深海热液区发现气态水. [2020-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-20).

- ^ Perkins, W. G. Mount Isa silica dolomite and copper orebodies; the result of a syntectonic hydrothermal alteration system. Economic Geology. 1984, 79 (4): 601. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.79.4.601.

- ^ The dawn of deep ocean mining. The All I Need. 2006 [2013-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-03).

- ^ Birney, K.; et al.. Potential Deep-Sea Mining of Seafloor Massive Sulfides: A case study in Papua New Guinea (PDF). University of California, Santa Barbara, B. [2013-04-21]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-09-23).

- ^ Treasures from the deep. Chemistry World (Royal Society of Chemistry). January 2007 [2013-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2016-06-04).

- ^ Devey, C.W.; Fisher, C.R.; Scott, S. Responsible Science at Hydrothermal Vents (PDF). Oceanography. 2007, 20 (1): 162–72. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2007.90. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-23).

- ^ Johnson, M. Oceans need protection from scientists too. Nature. 2005, 433 (7022): 105. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..105J. PMID 15650716. doi:10.1038/433105a.

- ^ Johnson, M. Deepsea vents should be world heritage sites. MPA News. 2005, 6: 10 [2013-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-18).

- ^ Tyler, P.; German, C.; Tunnicliff, V. Biologists do not pose a threat to deep-sea vents. Nature. 2005, 434 (7029): 18. Bibcode:2005Natur.434...18T. PMID 15744272. doi:10.1038/434018b.

扩展阅读

编辑- Van Dover CL, Humphris SE, Fornari D, Cavanaugh CM, Collier R, Goffredi SK, Hashimoto J, Lilley MD, Reysenbach AL, Shank TM, Von Damm KL, Banta A, Gallant RM, Gotz D, Green D, Hall J, Harmer TL, Hurtado LA, Johnson P, McKiness ZP, Meredith C, Olson E, Pan IL, Turnipseed M, Won Y, Young CR 3rd, Vrijenhoek RC. Biogeography and ecological setting of Indian Ocean hydrothermal vents. Science. 2001, 294 (5543): 818–23. Bibcode:2001Sci...294..818V. PMID 11557843. doi:10.1126/science.1064574.

- Van Dover, Cindy Lee. The Ecology of Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents. Princeton University Press. 2000. ISBN 0-691-04929-7.

- Beatty JT, Overmann J, Lince MT, Manske AK, Lang AS, Blankenship RE, Van Dover CL, Martinson TA, Plumley FG. An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005, 102 (26): 9306–10. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9306B. PMC 1166624 . PMID 15967984. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503674102.

- Glyn Ford and Jonathan Simnett, Silver from the Sea, September/October 1982, Volume 33, Number 5, Saudi Aramco World Accessed 17 October 2005

- Ballard, Robert D., 2000, The Eternal Darkness, Princeton University Press.

- http://www.botos.com/marine/vents01.html#body_4 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Anaerobic respiration on tellurate and other metalloids in bacteria from hydrothermal vent fields in the eastern pacific ocean (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Andrea Koschinsky, Dieter Garbe-Schönberg, Sylvia Sander, Katja Schmidt, Hans-Hermann Gennerich and Harald Strauss. Hydrothermal venting at pressure-temperature conditions above the critical point of seawater, 5°S on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geology. August 2008, 36 (8): 615–618 [18 June 2010]. doi:10.1130/G24726A.1. (原始内容存档于2010-06-25).

- Catherine Brahic. Found: The hottest water on Earth. New Scientist. 4 August 2008 [18 June 2010]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-12).

- Josh Hill. 'Extreme Water' Found at Atlantic Ocean Abyss. The Daily Galaxy. 5 August 2008 [18 June 2010]. (原始内容存档于2017-11-07).

外部链接

编辑- Ocean Explorer (www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov) (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) - Public outreach site for explorations sponsored by the Office of Ocean Exploration.

- Hydrothermal Vents Video (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) - The Smithsonian Institution's Ocean Portal

- Vent geochemistry (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- a good overview of hydrothermal vent biology, published in 2006 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) (PDF)

- Images of Hydrothermal Vents in Indian Ocean- Released by National Science Foundation (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- How to Build a Hydrothermal Vent Chimney (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer YouTube Channel (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)