环境问题

环境问题(英语:Environmental issues)指的是对生态系统功能所造成的破坏。[1]此外,这些问题或由人类所造成(参见人类对环境的影响),[2]也可能是自然界本身所产生。当受损的生态系统无法恢复时,会被认为是严重问题,如果预测注定要崩溃,则被认为是属于灾难性的。

环境保护是为环境和人类的利益而在个人、组织或政府层面上进行保护自然环境的措施。环境保护主义是一种社会运动,也是种环境运动,透过倡导、立法、教育和行动主义的手段来解决这类问题。[3]

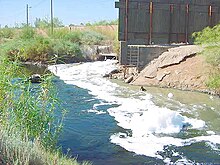

人类造成环境破坏是个全球性、持续存在的问题。[4]水污染会为海洋生物带来问题。[5]大多数学者认为根据地球限度理论,人类依据永续性的方式生活,地球生态系统可容纳的人口高峰将落在90-100亿之间。[6][7][8]大部分的环境问题是由世界上最富有的人群因过度消费所造成。[9][10][11]联合国环境署在2021年发布名为《与自然和平共处(Making Peace With Nature)》报告中提出,如果各方努力实现永续发展目标,如污染、气候变化和生物多样性丧失等主要危机将可解决。[12]

类型

编辑目前的主要环境问题包括有气候变化、污染、环境退化和资源枯竭。保育运动人士发起游说以保护濒危物种和任何具有生态价值的自然区域。联合国把国际环境问题归纳有三个具有关键性,称为地球三重危机:气候变化、污染和生物多样性丧失。[13]

人类影响

编辑人类对环境的影响(英语:Human impact on the environment,或称为人为影响(英语:anthropogenic impact))指的是人类直接或间接对生态环境、[14]生态系统、生物多样性和自然资源[15][16]所造成的改变。人类改变环境以适应自身建成环境的需求已产生严重的影响,[17][18]包括有气候变化、[14][19]环境退化[14](如海洋酸化[14][20])、大规模物种灭绝和生物多样性丧失、[21][22][23][24]生态危机以及生态崩溃。造成这类规模扩及全球的环境损害(直接或间接所产生)的人类活动包括有人口增长、[25][26]过度消费、过度开发、污染和森林砍伐。其中有些问题,包括有气候变化和生物多样性丧失,已被认为是危及人类生存的全球灾难危机。[27][28]

环境退化

编辑本节摘自环境退化。

环境退化是指因空气、水和土壤等的品质恶化,造成资源枯竭而发生环境恶化、生态系统遭破坏、栖息地破坏、野生动物灭绝,以及环境污染。任何被认为对环境有害,或是不良的变化或干扰均可定义为环境退化。[29]

环境问题可定义为任何人类活动对环境(包括其生物和物理特征)造成的负面影响。一些导致人们担忧的主要环境挑战包括空气污染、水污染、自然环境污染、垃圾污染等。[30]

环境退化是联合国处理威胁、挑战和变化高级别小组针对全球面临的十大威胁正式提出警告的其中之一。联合国降低灾难风险办公室将环境退化定义为"环境满足社会和生态目标及需求的能力降低"。[31]环境退化有多种类型,当发生栖息地破坏或自然资源耗尽时,环境就会退化。解决此一问题的方式包括环境保护和环境资源管理。由于管理不善而发生的环境退化也会导致环境冲突(社区组织起而对抗造成环境管理不善的机构)。

环境冲突

编辑本节摘自环境冲突。

环境冲突或生态分配冲突(ecological distribution conflict,EDC)是由于环境退化或环境资源分配不均而引发的社会冲突。[32][33][34]截至2020年4月,专门登载全球环境冲突事件的网站《环境正义地图集》就记录有3,100起事件,并强调另有更多冲突并未列入其中。[32]参与这类冲突的各方包括当地受到影响的社区、州、公司和投资者,以及社会或环境运动团体,[35][36]典型的事件是环境捍卫者在保护他们的家园免受资源剥夺或危险废弃物弃置的影响。[32]资源开采和危险废物弃置活动常造成资源稀缺(例如过度捕捞或森林砍伐)、污染环境,并导致人类和自然的生存空间退化,最终导致冲突。[37]环境冲突的一个特例是林业冲突(或称森林冲突),此种冲突"被广泛视为不同利益团体之间,针对与森林政策和森林资源利用有关的价值观和问题,所发生不同强度的斗争"。[38]全球在过去几十年里有越来越多的此类事件发生。[39]

环境冲突常集中在环境正义议题、原住民权利、农民权利或对依赖海洋为生社区的威胁。[32]地方冲突越来越受环境正义运动跨国网络的影响。[32][40]

环境冲突可能会让应对自然灾害变得复杂或加剧现有冲突 - 特别是在地缘政治争端或社区人民被迫流离失所,变成环境难民的情况下。[41][34][42]

社会环境冲突、环境冲突或生态分配冲突(EDC)等名词有时可互换使用。对这些冲突的研究涉及生态经济学、政治生态学和环境正义等领域。

成本

编辑气候变化经济分析(英语:Economic analysis of climate change)叙述如何应用经济思维、工具和技术来估算气候变化造成损害的程度和分布,还为大至涵盖全球,小至只包括家庭于缓解和调适的政策和方法提供资讯。这个主题还包括替代经济方法,例如生态经济学和去增长。在气候变化影响、调适和缓解之间的权衡取舍,透过成本效益分析予以分辨。针对气候变化进行成本效益分析,使用的是综合评估模型(integrated assessment models,IAM),这类模型将自然科学、社会科学和经济学的各个方面予以结合运用。气候变化对经济的整体影响不易估计,但确会随着气温升高后而增加。[43]

气候变化影响可作为一种经济成本来衡量。[44]:936-941这对市场影响而言特别适合,因其牵涉到市场活动,会直接影响到国内生产毛额(GDP) 。然而所产生的非市场影响(例如对人类健康和生态系统的影响)则难以货币形式表达(货币化)。因此对气候变化作经济分析具有挑战性,主要这是种长期问题,且在国家内部和国家之间存在重大的分配问题。此外,它还涉及气候变化造成的物理损害、人类应对和未来社会经济发展方面均有不确定性。行动

编辑环境正义

编辑本节摘自环境正义。

环境正义(或称生态正义(eco-justice))是一种针对环境不公的社会运动,当贫穷或边缘化社区受到危险废弃物、资源开采和他们无法从中受益的土地利用的伤害时,就会引发这种运动。[45]目前已有数百项针对此种运动的研究,报告中显示全球环境危害并非以均匀方式分布。[46]

环境运动于1980年代从美国开始。这种运动深受美国民权运动的影响,议题聚焦于富裕国家内部的环境种族主义。该运动后来扩大到把性别、国际环境不公以及发生于边缘群体的不平等现象都包括在内。当此类运动在富裕国家取得某种程度的成功,对于环境问题的注意力又转移到全球南方(Global South,参见南北分歧)如资源剥夺主义或全球废弃物交易)的议题,导致环境正义运动变得更为全球化,其中有些已由联合国予以阐明。此运动与原住民土地权和健康环境权运动发生重叠。[34]

环境正义运动的目标是帮助边缘社区能自主做出影响其生活环境的决策。全球环境正义运动源自地方环境冲突,其中环境捍卫者经常就此与资源开采或其他产业的跨国公司发生对抗行动。而地方性的冲突越来越受到跨国环境正义网络的影响。[32][47]

研究环境正义学者创作大量跨学科社会科学文献,其中有些可增进政治生态学、环境法学以及正义和永续性的内涵。[45][48]

环境法

编辑本节摘自环境法。

环境法是用于保护环境的法律,[49]是规范人类如何与环境互动的法律、法规、协议和普通法的总和,[50]其中包括环境法规、有关森林、矿物或渔业等自然资源管理的法律,以及环境影响评估等相关主题。环境法被视为一种法律体系,涉及保护生物(包括人类)免受人类活动立即或最终对其或其物种造成直接或间接,或是对其依赖的媒介及栖息地的伤害。[51]

环境影响评估

编辑本节摘自环境影响评估。

环境影响评估(Environmental Impact assessment,EIA)是在决定推动拟议行动之前对计划、政策、计划或实际项目的环境后果所进行的评估。在这种情况下,所谓"环境影响评估"一词通常用于个人或公司要执行的项目,而"策略性环境评估(strategic environmental assessment,SEA)"一词则适用于国家机关经常提出的政策、计划和方案。[52][53]EIA是管理环境的工具,是项目审批和决策中包含的元素。[54]环境影响评估可能会受到有关公众参与和决策行政程序的管辖,也可能受到司法的审查。

评估的目的是确保决策者在决定是否进行项目时将环境影响列入考虑。国际环境影响评估协会(IAIA)将环境影响评估定义为"在做出重大决定和承诺之前,先识别、预测、评估和减轻开发提案所具有生物物理、社会和其他相关影响的程序"。[55]评估的独特之处在于其并未要求项目达到预定的环境结果,而是要求决策者在过程中考虑环境价值,并根据详细的环境研究和公众对潜在环境影响的评论来证明这些决策的合理性。[56]

环保运动

编辑本节摘自环保运动。

环保运动(有时称为生态运动)是一项社会运动,目的在保护自然界免受有害环境行为的影响,以创造绿色生活。[57]环保人士主张透过改变公共政策和个人行为改变来公正和永续地管理资源和环境。[58]此运动认为人类是生态系统的参与者(而非敌人),其重点是生态、健康和人权。

环保运动是一种国际运动,以一系列环保组织(包含企业与草根组织)为代表,各国的情况各不相同。由于参与者众多、信仰各异,且因强烈,以及偶尔的投机性质,运动中倡导的目标并非完全一致。从最广泛的意义上讲,此运动包括普通公民、专业人士、拥抱环保主义的宗教信仰者、政治家、科学家、非营利组织以及某些个人倡导者。

环境组织

编辑环境问题由政府组织在区域、国家或国际上的不同的层面予以处理。

最大的国际机构是联合国环境署(成立于1972年)。国际自然保护联盟汇集有83个国家、108个政府机构、766个非政府组织、81个国际组织,以及来自世界各国约1万名专家、科学家。[59]国际性非政府组织则例如有绿色和平组织、地球之友和世界自然基金会。各国政府制定环境政策并执行环境法,但其中的执行力度各不相同。

影片与其他流行文化

编辑有越来越多涉及环境问题的影片被制作,特别是针对气候变化与衍生的全球变暖及其他问题。

电影《不愿面对的真相》(美国前副总统艾尔·高尔于2006年推出的电影)提起大西洋经向翻转环流(AMOC)可能会停止,以及当北极冰盖融化而导致进入北大西洋的淡水流量增加,对欧洲气温的影响。

电影《明天过后》和名为《冰(Ice)》的英国电视剧都以夸张的场景来探讨与AMOC停止的相关后果。

美国科幻小说作者金·史丹利·罗宾逊的作品《降温五十度》是他的《首都科学》系列中的第二部作品,描述温盐环流停止,以及人类通过向海洋中添加大量盐来尽力恢复此环流的故事。

在军事科幻小说家伊恩道格拉斯的《星际医护兵(Star Corpsman)》 系列小说中,AMOC的停止引发早期盛冰期,到22世纪中叶,加拿大大部分地区和北欧均因此遭到冰雪覆盖。

参见

编辑问题

- 环境问题列表 (包括缓解与保育行动)

特定问题

参考文献

编辑- ^ Jhariya et al. 2022. ([//web.archive.org/web/20230217143622/https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128229767/natural-resources-conservation-and-advances-for-sustainability 页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) "Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability" Chapter 7.5 ISBN 978-0-12-822976-7

- ^ Human Impacts on the Environment. education.nationalgeographic.org. [2023-05-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-30) (英语).

- ^ Eccleston, Charles H. (2010). Global Environmental Policy: Concepts, Principles, and Practice (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Chapter 7. ISBN 978-1439847664.

- ^ McNeill, Z. Zane. Humans Destroying Ecosystems: How to Measure Our Impact on the Environment. 2022-09-07 [2023-05-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-09) (美国英语).

- ^ Marine Pollution. education.nationalgeographic.org. [2023-05-06]. (原始内容存档于2024-01-08) (英语).

- ^ Alberro, Heather. Why we should be wary of blaming 'overpopulation' for the climate crisis. The Conversation. [2020-12-31]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-20) (英语).

- ^ David Attenborough's claim that humans have overrun the planet is his most popular comment. www.newstatesman.com. 2020-11-04 [2021-08-03]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-03) (英语).

- ^ Dominic Lawson: The population timebomb is a myth The doom-sayers are becoming more fashionable just as experts are coming to the view it has all been one giant false alarm. The Independent (UK). 2011-01-18 [2011-11-30]. (原始内容存档于2011-10-13).

- ^ Nässén, Jonas; Andersson, David; Larsson, Jörgen; Holmberg, John. Explaining the Variation in Greenhouse Gas Emissions Between Households: Socioeconomic, Motivational, and Physical Factors. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 2015, 19 (3): 480–489 [2023-10-10]. ISSN 1530-9290. S2CID 154132383. doi:10.1111/jiec.12168. (原始内容存档于2024-02-18) (英语).

- ^ Moser, Stephanie; Kleinhückelkotten, Silke. Good Intents, but Low Impacts: Diverging Importance of Motivational and Socioeconomic Determinants Explaining Pro-Environmental Behavior, Energy Use, and Carbon Footprint. Environment and Behavior. 2017-06-09, 50 (6): 626–656 [2023-10-10]. ISSN 0013-9165. S2CID 149413363. doi:10.1177/0013916517710685. (原始内容存档于2022-11-03).

- ^ Lynch, Michael J.; Long, Michael A.; Stretesky, Paul B.; Barrett, Kimberly L. Measuring the Ecological Impact of the Wealthy: Excessive Consumption, Ecological Disorganization, Green Crime, and Justice. Social Currents. 2019-05-15, 6 (4): 377–395 [2023-10-10]. ISSN 2329-4965. S2CID 181366798. doi:10.1177/2329496519847491. (原始内容存档于2022-11-03).

- ^ Environment, U. N. Making Peace With Nature. UNEP - UN Environment Programme. 2021-02-11 [2022-02-18]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-19) (英语).

- ^ SDGs will address 'three planetary crises' harming life on Earth. UN News. 2021-04-27 [2022-02-18]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-26) (英语).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Climate Science Special Report – Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4), Volume I, Executive Summary. U.S. Global Change Research Program: 1–470. [2017-12-02]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-14).

This assessment concludes, based on extensive evidence, that it is extremely likely that human activities, especially emissions of greenhouse gases, are the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century. For the warming over the last century, there is no convincing alternative explanation supported by the extent of the observational evidence. In addition to warming, many other aspects of global climate are changing, primarily in response to human activities. Thousands of studies conducted by researchers around the world have documented changes in surface, atmospheric, and oceanic temperatures; melting glaciers; diminishing snow cover; shrinking sea ice; rising sea levels; ocean acidification; and increasing atmospheric water vapor.

- ^ Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. and Ferry, P.A. Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land. Biology Letters. 2010, 6 (4): 544–547. PMC 2936204 . PMID 20106856. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024.

- ^ Hawksworth, David L.; Bull, Alan T. Biodiversity and Conservation in Europe. Springer. 2008: 3390. ISBN 978-1402068645.

- ^ Stockton, Nick. The Biggest Threat to the Earth? We Have Too Many Kids. Wired.com. 2015-04-22 [2017-11-24]. (原始内容存档于2019-12-18).

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R. World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency. BioScience. 2019-11-05 [2019-11-08]. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278 . (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

Still increasing by roughly 80 million people per year, or more than 200,000 per day (figure 1a–b), the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity. There are proven and effective policies that strengthen human rights while lowering fertility rates and lessening the impacts of population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss. These policies make family-planning services available to all people, remove barriers to their access and achieve full gender equity, including primary and secondary education as a global norm for all, especially girls and young women (Bongaarts and O’Neill 2018).

- ^ Cook, John. Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters. 2016-04-13, 11 (4): 048002. Bibcode:2016ERL....11d8002C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002 .

The consensus that humans are causing recent global warming is shared by 90%–100% of publishing climate scientists according to six independent studies

- ^ Increased Ocean Acidity. Epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 30 August 2016 [2017-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2011-06-23).

Carbon dioxide is added to the atmosphere whenever people burn fossil fuels. Oceans play an important role in keeping the Earth's carbon cycle in balance. As the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere rises, the oceans absorb a lot of it. In the ocean, carbon dioxide reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid. This causes the acidity of seawater to increase.

- ^ Leakey, Richard and Roger Lewin, 1996, The Sixth Extinction : Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind, Anchor, ISBN 0-385-46809-1

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Barnosky, Anthony D.; Garcia, Andrés; Pringle, Robert M.; Palmer, Todd M. Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Science Advances. 2015, 1 (5): e1400253. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0253C. PMC 4640606 . PMID 26601195. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253.

- ^ Pimm, S. L.; Jenkins, C. N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T. M.; Gittleman, J. L.; Joppa, L. N.; Raven, P. H.; Roberts, C. M.; Sexton, J. O. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection (PDF). Science. 2014-05-30, 344 (6187): 1246752 [2016-12-15]. PMID 24876501. S2CID 206552746. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-01-07).

The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption.

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R; Dirzo, Rodolfo. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. PNAS. 2017-05-23, 114 (30): E6089–E6096. PMC 5544311 . PMID 28696295. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704949114 .

Much less frequently mentioned are, however, the ultimate drivers of those immediate causes of biotic destruction, namely, human overpopulation and continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich. These drivers, all of which trace to the fiction that perpetual growth can occur on a finite planet, are themselves increasing rapidly.

- ^ Crist, Eileen; Ripple, William J.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Rees, William E.; Wolf, Christopher. Scientists' warning on population (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 2022, 845: 157166 [2022-12-28]. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.845o7166C. PMID 35803428. S2CID 250387801. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157166. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-11-12).

- ^ Nordström, Jonas; Shogren, Jason F.; Thunström, Linda. Do parents counter-balance the carbon emissions of their children?. PLOS One. 2020-04-15, 15 (4): e0231105. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1531105N. PMC 7159189 . PMID 32294098. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231105 .

It is well understood that adding to the population increases CO2 emissions.

- ^ New Climate Risk Classification Created to Account for Potential "Existential" Threats. Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scripps Institution of Oceanography. 2017-09-14 [2017-11-24]. (原始内容存档于2017-09-15).

A new study evaluating models of future climate scenarios has led to the creation of the new risk categories "catastrophic" and "unknown" to characterize the range of threats posed by rapid global warming. Researchers propose that unknown risks imply existential threats to the survival of humanity.

- ^ Torres, Phil. Biodiversity loss: An existential risk comparable to climate change. Thebulletin.org. Taylor & Francis. 2016-04-11 [2017-11-24]. (原始内容存档于2016-04-13).

- ^ Johnson, D.L., S.H. Ambrose, T.J. Bassett, M.L. Bowen, D.E. Crummey, J.S. Isaacson, D.N. Johnson, P. Lamb, M. Saul, and A.E. Winter-Nelson. 1997. Meanings of environmental terms. Journal of Environmental Quality 26: 581–589.

- ^ Types of Environmental Issues. [2023-12-18]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-08).

- ^ ISDR : Terminology. The International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. 2004-03-31 [2010-06-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-03).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 Scheidel, Arnim; Del Bene, Daniela; Liu, Juan; Navas, Grettel; Mingorría, Sara; Demaria, Federico; Avila, Sofía; Roy, Brototi; Ertör, Irmak; Temper, Leah; Martínez-Alier, Joan. Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview. Global Environmental Change. 2020-07-01, 63: 102104. ISSN 0959-3780. PMC 7418451 . PMID 32801483. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104 (英语).

- ^ Lee, James R. What is a field and why does it grow? Is there a field of environmental conflict?. Environmental Conflict and Cooperation. Routledge. 2019-06-12: 69–75. ISBN 978-1-351-13924-3. S2CID 198051009. doi:10.4324/9781351139243-9.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Libiszewski, Stephan. What is an Environmental Conflict? (PDF). Journal of Peace Research. 1991, 28 (4): 407–422 [2023-12-18]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-03-25).

- ^ Cardoso, Andrea. Behind the life cycle of coal: Socio-environmental liabilities of coal mining in Cesar, Colombia. Ecological Economics. December 2015, 120: 71–82. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.004.

- ^ Orta-Martínez, Martí; Finer, Matt. Oil frontiers and indigenous resistance in the Peruvian Amazon. Ecological Economics. December 2010, 70 (2): 207–218. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.022 (英语).

- ^ Hellström, Eeva. Conflict cultures: qualitative comparative analysis of environmental conflicts in forestry. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Society of Forest Science [and] Finnish Forest Research Institute. 2001. ISBN 951-40-1777-3. OCLC 47207066.

- ^ Hellström, Eeva. Conflict cultures: qualitative comparative analysis of environmental conflicts in forestry. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Society of Forest Science [and] Finnish Forest Research Institute. 2001. ISBN 951-40-1777-3. OCLC 47207066.

- ^ Mola-Yudego, Blas; Gritten, David. Determining forest conflict hotspots according to academic and environmental groups. Forest Policy and Economics. October 2010, 12 (8): 575–580. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2010.07.004 (英语).

- ^ Martinez Alier, Joan; Temper, Leah; Del Bene, Daniela; Scheidel, Arnim. Is there a global environmental justice movement?. Journal of Peasant Studies. 2016, 43 (3): 731–755. S2CID 156535916. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198.

- ^ Environment, Conflict and Peacebuilding. International Institute for Sustainable Development. [2022-02-18]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-08) (英语).

- ^ Mason, Simon; Spillman, Kurt R. Environmental Conflicts and Regional Conflict Management. WELFARE ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT – Volume II. EOLSS Publications. 2009-11-17. ISBN 978-1-84826-010-8 (英语).

- ^ Luomi, Mari. Global Climate Change Governance: The search for effectiveness and universality (报告). International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). 2020. JSTOR resrep29269.

- ^ Smith, J. B.; et al. 19. Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis (PDF). McCarthy, J. J.; et al (编). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. 2001: 913–970 [2022-01-19]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-01-22).

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Schlosberg, David. (2007) Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Malin, Stephanie. Environmental justice and natural resource extraction: intersections of power, equity and access. Environmental Sociology. 2019-06-25, 5 (2): 109–116. S2CID 198588483. doi:10.1080/23251042.2019.1608420 .

- ^ Martinez Alier, Joan; Temper, Leah; Del Bene, Daniela; Scheidel, Arnim. Is there a global environmental justice movement?. Journal of Peasant Studies. 2016, 43 (3): 731–755. S2CID 156535916. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198.

- ^ Miller, G. Tyler Jr. Environmental Science: Working With the Earth 9th. Pacific Grove, California: Brooks/Cole. 2003: G5. ISBN 0-534-42039-7.

- ^ Phillipe Sands (2003) Principles of International Environmental Law. 2nd Edition. p. xxi Available at [1] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Accessed 2020-02-19

- ^ What is Environmental Law? | Becoming an Environmental Lawyer. [2023-06-28]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-24) (美国英语).

- ^ ENVIRONMENTAL LAW I (PDF). NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, SCHOOL OF LAW. [2023-11-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-03-30).

- ^ MacKinnon, A. J., Duinker, P. N., Walker, T. R. (2018). The Application of Science in Environmental Impact Assessment. Routledge.

- ^ Eccleston, Charles H. (2011). Environmental Impact Assessment: A Guide to Best Professional Practices (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Chapter 5. ISBN 978-1439828731

- ^ Caves, R. W. Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. 2004: 227.

- ^ Principle of Environmental Impact Assessment Best Practice (PDF). International Association for Impact Assessment. 1999 [2020-09-15]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-05-07).

- ^ Holder, J., (2004), Environmental Assessment: The Regulation of Decision Making, Oxford University Press, New York; For a comparative discussion of the elements of various domestic EIA systems, see Christopher Wood Environmental Impact Assessment: A Comparative Review (2 ed, Prentice Hall, Harlow, 2002).

- ^ McCormick, John. Reclaiming Paradise: The Global Environmental Movement. Indiana University Press. 1991 [2023-04-08]. ISBN 978-0-253-20660-2. (原始内容存档于2023-04-08) (英语).

- ^ Hawkins, Catherine A. Sustainability, human rights, and environmental justice: Critical connections for contemporary social work. Critical Social Work. 2010, 11 (3) [8 April 2023]. ISSN 1543-9372. S2CID 211405454. doi:10.22329/csw.v11i3.5833 . (原始内容存档于2023-03-05) (英语).

- ^ About. IUCN. 2014-12-03 [2017-05-20]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-15) (英语).

引用作品

编辑- Chapin, F. Stuart; Matson, Pamela A.; Vitousek, Peter. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. Springer Science+Business Media. 2011-09-02 [2022-10-04]. ISBN 978-1-4419-9504-9 (英语).

- Hawksworth, David L.; Bull, Alan T. Biodiversity and Conservation in Europe. Springer. 2008: 3390. ISBN 978-1402068645.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Ferry, P.A. Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land. Biology Letters. 2010, 6 (4): 544–547. PMC 2936204 . PMID 20106856. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024.

- Steffen, Will; Sanderson, Regina Angelina; Tyson, Peter D.; Jäger, Jill; Matson, Pamela A.; Moore III, Berrien; Oldfield, Frank; Richardson, Katherine; Schellnhuber, Hans-Joachim. Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure. Springer Science+Business Media. 2006-01-27 [2022-10-04]. ISBN 978-3-540-26607-5 (英语).