腹主动脉瘤

腹主动脉瘤(英语:abdominal aortic aneurysm, AAA[1]),为腹主动脉局部扩大,其横径大于3公分或超过正常横径之50%[2]。除非腹主动脉瘤破裂,否则通常无症状[2]。偶尔造成腹部、背部、腿部等处疼痛[3],较大的腹主动脉瘤,有时甚至可借由腹部触诊感觉到搏动。破裂时可能造成腹部或背部疼痛、低血压、或短暂失去意识[2][4]。

| 腹主动脉瘤 / Abdominal aortic aneurysm | |

|---|---|

| |

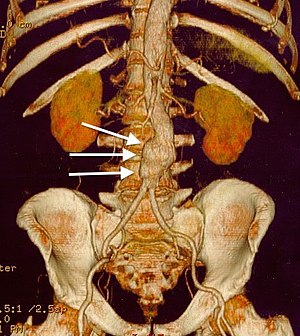

| 腹主动脉瘤的电脑断层重建影像(白色箭头处) | |

| 类型 | 主动脉瘤、疾病 |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 血管外科 |

| ICD-11 | BD50.4 |

| ICD-10 | I71.3, I71.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 441.3, 441.4 |

| OMIM | 100070 |

| DiseasesDB | 792 |

| MedlinePlus | 000162 |

| eMedicine | med/3443 emerg/27 radio/1 |

| MeSH | D017544 |

腹主动脉瘤大部分发生在50岁以上,尤其男性以及具有家族史的病患[2]。其他危险因子包括抽烟、高血压、以及心血管疾病[5]。基因方面如马凡氏症候群及橡皮人症候群,可能增加罹病风险。腹主动脉瘤为最常见的动脉瘤[6],大约85%位在肾脏以下的主动脉,其余则在肾脏同高或以上的位置[2]。在美国,建议65岁至75岁且抽烟的男性,接受超声波筛检[7]。在英国,则建议所有65岁以上男性应接受筛检[2]。澳洲则没有筛检准则。一旦发现腹主动脉瘤后,需要定期作超声波检查[8]。

戒烟或不吸烟为预防此疾病的最佳方法。其他则包含治疗高血压、减少高胆固醇的现象、避免体重过重。当腹主动脉瘤横径,在男性超过5.5公分,在女性超过5公分,则建议接受手术[2]。其他修补手术的适应症包括有症状及大小快速增加[3]。修补可借由开腹手术或血管内动脉瘤修补[2]。比起开腹手术,血管内动脉瘤修补虽然有以下好处:短期内死亡风险较低、住院时间较短;但必要时仍需要接受开腹手术[2][9][10]。长期来看,两者的预后情况没有很大的差别[11],除了EVAR可能要重复开刀的可能性较高[12]。

腹主动脉瘤影响约2%至8%的65岁以上男性,而男性的疾病发生率是女性的四倍。若动脉瘤横径小于5.5公分,隔年的破裂风险小于1%;横径在5.5至7公分之间者,则为10%;大于7公分更高达33%。破裂后的死亡率是85%至90%[2]。1990年,腹主动脉瘤造成10万人死亡,而在2013年,更造成15万2千人死亡。在2009年的美国,腹主动脉瘤则造成1万至1万8千人死亡[6]。

参考资料

编辑- ^ Logan, Carolynn M.; Rice, M. Katherine. Logan's Medical and Scientific Abbreviations. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. 1987: 3. ISBN 0-397-54589-4.

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 Kent KC. Clinical practice. Abdominal aortic aneurysms.. The New England Journal of Medicine. 27 November 2014, 371 (22): 2101–8. PMID 25427112. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1401430.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Upchurch GR, Schaub TA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am Fam Physician. 2006, 73 (7): 1198–204. PMID 16623206.

- ^ Spangler R, Van Pham T, Khoujah D, Martinez JP. Abdominal emergencies in the geriatric patient.. International journal of emergency medicine. 2014, 7 (1): 43. PMID 25635203. doi:10.1186/preaccept-3303381914150346.

- ^ Wittels K. Aortic emergencies.. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. November 2011, 29 (4): 789–800, vii. PMID 22040707. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.09.015.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Aortic Aneurysm Fact Sheet. cdc.gov. July 22, 2014 [3 February 2015]. (原始内容存档于2017-05-02).

- ^ Cinà CS, Devereaux PJ. Review: population-based screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm reduces cause-specific mortality in older men. ACP J. Club. 2005, 143 (1): 11 [2015-04-12]. PMID 15989299. (原始内容存档于2016-03-03).

- ^ Robinson, D; Mees, B; Verhagen, H; Chuen, J. Aortic aneurysms - screening, surveillance and referral.. Australian family physician. June 2013, 42 (6): 364–9. PMID 23781541.

- ^ Thomas DM, Hulten EA, Ellis ST, Anderson DM, Anderson N, McRae F, Malik JA, Villines TC, Slim AM. Open versus Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in the Elective and Emergent Setting in a Pooled Population of 37,781 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.. ISRN cardiology. 2014, 2014: 149243. PMID 25006502. doi:10.1155/2014/149243.

- ^ Biancari F, Catania A, D'Andrea V. Elective endovascular vs. open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients aged 80 years and older: systematic review and meta-analysis.. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. November 2011, 42 (5): 571–6. PMID 21820922. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.07.011.

- ^ Paravastu SC, Jayarajasingam R, Cottam R, Palfreyman SJ, Michaels JA, Thomas SM. Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm.. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 23 January 2014, 1: CD004178. PMID 24453068. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004178.pub2.

- ^ Ilyas S, Shaida N, Thakor AS, Winterbottom A, Cousins C. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) follow-up imaging: the assessment and treatment of common postoperative complications.. Clinical radiology. February 2015, 70 (2): 183–196. PMID 25443774. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2014.09.010.