大冠鹫

大冠鹫(学名:Spilornis cheela)又名冠蛇雕、冕蛇雕、食蛇雕,粤语俗称食蛇鹰,是一种中大型猛禽,属于鹰科一员。分布于热带亚洲的森林栖地中。在它广泛分布的印度次大陆、东南亚和东亚范围内,存在显著的变异,一些权威机构更倾向于将其数个亚种视为完全独立的物种。[2] 过去,包括菲律宾蛇雕(S. holospila)、安达曼蛇雕(S. elgini)和南尼科巴蛇雕(S. klossi)在内的数个物种被视为大冠鹫的亚种。所有复合种内的成员均拥有看似庞大的头部,头后部的长羽毛赋予它们鬃毛和冠状的外观。脸部裸露且呈黄色,与蜡膜相连,而强健的脚则无羽毛覆盖且有厚重的鳞片。它们以宽广的翅膀和尾巴飞越森林树冠,翼和尾上有宽阔的白色与黑色条纹。它们经常发出响亮、刺耳且熟悉的两或三音节叫声。它们经常以蛇为食,因此得名,并与短趾雕属(Circaetus)一起归类于蛇雕亚科。

| 大冠鹫 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 指名亚种,摄于印度奈尼塔尔 | |

| 亚种melanotis叫声 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 脊索动物门 Chordata |

| 纲: | 鸟纲 Aves |

| 目: | 鹰形目 Accipitriformes |

| 科: | 鹰科 Accipitridae |

| 属: | 蛇雕属 Spilornis |

| 种: | 大冠鹫 S. cheela

|

| 二名法 | |

| Spilornis cheela Latham, 1790

| |

描述

编辑雅拉国家公园、斯里兰卡

大冠鹫身长约55至75公分,翼展约150至170公分,成鸟背面和后颈为黑褐色,胸部和腹部和翼下为淡褐色,胸腹有白色斑点,停栖时可见明显冠羽,在高空时翼开展保持以浅V字型翱翔,尾巴和翼下后缘为黑色有一条白色横带。

这种中大型的深褐色雕体型壮硕,翼圆短而尾巴短。其短小的黑白扇形枕冠使其脖子显得粗壮。裸露的脸部皮肤和脚皆为黄色。腹部带有白色和黄褐色斑点。当站立时,翼尖不及尾尖。飞行时,宽阔的桨状翅膀呈浅V形。尾部和飞行羽毛的下方为黑色,带有宽广的白色条纹。幼鸟头部显示大量白色。[3][4] 跗跖部无羽毛覆盖,且被六角形鳞片覆盖。上喙无向下弯曲的尖端。[5]

大小

编辑这种蛇雕的各个亚种之间表现出非同寻常的尺寸变异。成年大冠鹫的总长度可变动于41至75 cm(16至30英寸),翼展可变动于89至169 cm(2英尺11英寸至5英尺7英寸)。[6][7][8] 最大的比例出现在指名种S. c. cheela中,雄鸟的翼弦长度为468至510 mm(18.4至20.1英寸),雌鸟为482至532 mm(19.0至20.9英寸),尾长为295至315 mm(11.6至12.4英寸),跗跖长度为100至115 mm(3.9至4.5英寸)。相比之下,可能最小的亚种S. c. minimus,雄鸟的翼弦长度为257至291 mm(10.1至11.5英寸),雌鸟为288至304 mm(11.3至12.0英寸),尾长约191 mm(7.5英寸),跗跖长度约76 mm(3.0英寸)。[8] 体重的报告比较零星,但估计不同亚种之间的体重可能相差三倍之多。[8][9] 在非常小的亚种如S. c. asturinus中,雄鸟的体重被发现为420 g(15 oz),雌鸟为565 g(19.9 oz)。[8] 在S. c. palawanesis中,雄鸟体重为688 g(24.3 oz),雌鸟为853 g(30.1 oz)。[10] 来自婆罗洲的大冠鹫,如S. c. pallidus,可能介于625、1,130 g(22.0、39.9 oz)之间。[8][11] 大陆形式通常较大,但一个相对较小的大陆亚种S. c. burmanicus的体重被报导为900 g(32 oz)。[12] 在S. c. hoya亚种中,体重更高,平均1,207 g(42.6 oz)。与此同时,同一亚种中的8只雄性平均体重为1,539 g(54.3 oz),6只雌性平均体重为1,824 g(64.3 oz)。[13][14] 在某些情况下,大冠鹫的估计体重可达约2,300 g(81 oz)。[15]

分类

编辑西表岛、冲绳

大冠鹫与短趾雕属(Circaetus)的蛇雕同属于蛇雕亚科。[16]

指名亚种的喉部为黑色,而印度半岛的形式则为棕色。随着纬度的变化,存在着由北向南体型逐渐减少的渐变性变化。[3] 小岛屿的种群通常比亚洲大陆/大岛屿的种群小,这是一种称为岛屿侏儒化的现象。[2][17] 在热带亚洲广泛的分布范围内,已提出21个亚种:[2]

- S. c. batu 来自苏门答腊南部和巴图,

- S. c. bido 来自爪哇和巴厘岛,

- S. c. burmanicus 分布于印度支那大部分地区,

- S. c. hoya 来自台湾,

- S. c. malayensis 来自泰国-马来半岛和苏门答腊北部,

- S. c. melanotis 分布于印度半岛,

- S. c. palawanensis 来自巴拉望,

- S. c. pallidus 来自婆罗洲北部,

- S. c. richmondi 来自婆罗洲南部,

- S. c. ricketti 分布于越南北部和中国南部,

- S. c. rutherfordi 来自海南岛,以及

- S. c. spilogaster 来自斯里兰卡。

其余亚种均限于小岛屿:

- S. c. abbotti(锡默卢蛇雕)来自锡默卢岛,

- S. c. asturinus(尼亚斯蛇雕)来自尼亚斯岛,

- S. c. baweanus(巴威蛇雕)来自巴威,

- S. c. davisoni 分布于安达曼群岛,

- S. c. minimus(中央尼科巴蛇雕)来自尼科巴群岛中部,

- S. c. natunensis(纳土纳蛇雕)来自纳土纳群岛,

- S. c. perplexus(琉球蛇雕)来自琉球,以及

- S. c. sipora(明打威蛇雕)来自明打威群岛。

最后七个(括号内为英文名称)有时被视为独立的物种。[2] 虽然大冠鹫整体上分布广泛且相对常见,但有些仅限于小岛屿的种群被认为数量相对较少,可能仅有数百只。[2]

分布

编辑大冠鹫分布很广,在东亚、南亚、东南亚都有发现,从喜马拉雅山到印度和斯里兰卡到中国南方和台湾及中南半岛、菲律宾、印度尼西亚,筑巢在森林近水边的树冠,鸟巢以树枝条构成,且一巢只生一个蛋。

行为与生态

编辑大冠鹫是一种爬行动物捕食者,经常在森林上空猎食,通常靠近湿润的草地,[21]捕食蛇和蜥蜴。它也被观察到捕食鸟类、两栖类、哺乳类、鱼类、白蚁和大型蚯蚓。[22][23] 它主要出现在低矮山丘和平原上有茂密植被的地区。此物种为留鸟,但在其分布区的某些地方,只在夏季出现。[3][24]

其叫声具有独特的Kluee-wip-wip特征,第一音符高且逐渐升高。它们经常在早晨晚些时候从它们的栖息处发出叫声,并在早晨随着热气流升空。[3] 在台湾南部,雄性比雌性有较大的活动范围。雄性的活动范围平均为16.7平方公里,而雌性约为7平方公里。[25] 当受到惊吓时,它们会竖起冠羽,使头部显得庞大且被颈毛环绕。[5] 它们有时会跟随地上的蛇。[26] 它们栖息在树叶繁茂的树木内部。[27] 在台湾对该物种进行的无线电追踪研究发现,这些鸟类一天中的98%时间都在栖息,通常在早晨觅食。它们似乎使用等待的方式来觅食。[28]

繁殖季节始于冬末,当时它们开始求偶并建立领域。它们在初夏产卵。旧巢在印度经常被修复和重复使用,但在槟城的研究发现它们每年都会建造新巢。[29] 在印度的一项研究中发现,大多数巢位于河边的树木上。巢是一个建在高树上的大平台。雌雄鸟会共同筑巢,但只有雌鸟负责孵卵。雌鸟觅食时,雄鸟负责守护。在印度中部,毛榄仁(Terminalia tomentosa)经常被使用,而在印度南部,毗黎勒(Terminalia bellirica)和阔叶黄檀(Dalbergia latifolia)经常被使用。[22] 在槟城,筑巢的树木通常很大且与其他树木隔离,为鸟类进出提供了充足的空间。巢内铺有从附近采集的绿叶,这些绿叶是倒置放在巢底的。[26][29] 一般每次产一颗蛋,但有时会产两颗蛋,每季仅成功抚育一只雏鸟。如果蛋遗失,约两到七周后会再产一颗蛋。蛋约在41天后孵化,幼鸟约两个月后离巢。亲鸟会保护巢穴。[5][30][31][32]

在大冠鹫的肠道中发现了多种内寄生线虫,包括Madelinema angelae。[33][34] 在台湾一只野生鸟类中观察到了由禽痘病毒感染引起的面部疣状病变。[35] 从该物种中还描述了多种体外寄生的羽虱,包括Kurodaia cheelae。[36] 在槟城,发现苍背山雀(Parus cinereus ambiguus)倾向于在靠近大冠鹫巢的地方筑巢,可能是因为雕能驱赶如乌鸦等掠食者而带来安全保障。它们还被发现会造访雕的巢,收集死去哺乳动物猎物遗留下来的毛皮。[29]

影音档

编辑外部链接

编辑参考资料

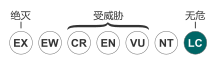

编辑- ^ Spilornis cheela. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. [1 October 2016]. 数据库资料包含说明此物种被编入无危级别的原因

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Ferguson-Lees, James & Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-8026-1

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Rasmussen, P.C.; Anderton, J.C. Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. 2005: 92–93.

- ^ Blanford, W.T. The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume 3. London: Taylor and Francis. 1895: 357–360.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Ali, S.; Ripley, S.D. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan 1 Second. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 1978: 329–334.

- ^ Clark, W.S., J. S. Marks, and G. M. Kirwan (2020). Crested Serpent-Eagle (Spilornis cheela), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- ^ Grewal, B., Pfister, O., & Harvey, B. (2002). A Photographic Guide to the Birds of India: And the Indian Subcontinent, Including Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka & the Maldives. Princeton University Press.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2001. ISBN 0-618-12762-3.

- ^ Dunning, John B. Jr. (编). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses 2nd. CRC Press. 2008. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- ^ Gamauf, A., Preleuthner, M., & Winkler, H. (1998). Philippine birds of prey: interrelations among habitat, morphology, and behavior. The Auk, 115(3), 713-726.

- ^ Artuti, A. K., Sari, M., Retnaningtyas, R. W., & Listyorini, D. (2020, November). A phylogenetic analysis of Crested Serpent Eagle (Spilornis cheela) based on cytochrome-c oxydase subunit I (COI): a stepping stone towards genetic conservation of raptors in Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 590, No. 1, p. 012008). IOP Publishing.

- ^ Brown, L. & Amadon, D. (1986) Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World. The Wellfleet Press. ISBN 978-1555214722.

- ^ Tsai, P. Y., Ko, C. J., Hsieh, C., Su, Y. T., Lu, Y. J., Lin, R. S., & Tuanmu, M. N. (2020). A trait dataset for Taiwan's breeding birds. Biodiversity data journal, 8.

- ^ Chou, T. C., Walther, B. A., & Lee, P. F. (2012). Spacing pattern of the Crested Serpent-eagle (spilornis cheela hoya) in Southern Taiwan. Taiwania, 57(1), 1-13.

- ^ Unwin, M., & Tipling, D. (2018). The Empire of the Eagle: An Illustrated Natural History. Yale University Press.

- ^ Lerner, H.R.L.; Mindell, D.P. Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2005, 37 (2): 327–46. PMID 15925523. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.010.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Mayr, E.; Cottrell, G.W. (编). Check-List of Birds of the World. Volume 1 Second. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. 1979: 311–315.

- ^ Nijman, V. The endemic Bawean Serpent-eagle Spilornis baweanus: habitat use, abundance and conservation. Bird Conservation International. 2006, 16 (2): 131–143. doi:10.1017/S0959270906000219 .

- ^ Oberholser, H.C. The birds of the Natuna Islands. Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 1923, 159: 18–21.

- ^ Sclater, W.L. Descriptions of new hawks. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 1918, 38 (245): 37–41.

- ^ Ueta, M.; Minton, J.S. Habitat preference of Crested Serpent Eagles in Southern Japan (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 1996, 30 (2): 99–100.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Gokula, V. Breeding ecology of the crested serpent eagle Spilornis cheela (Latham, 1790) (Aves: Accipitriformes: Accipitridae) in Kolli Hills, Tamil Nadu, India. Taprobanica. 2012, 4 (2): 77–82. doi:10.4038/tapro.v4i2.5059 .

- ^ Crested Serpent-Eagle | the Peregrine Fund.

- ^ Purandare, K. Attempt by the crested Serpent Eagle Spilornis cheela to seize the Indian cobra Naja naja. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 2002, 99 (2): 299.

- ^ Chou, T.; Walther, B.A.; Pei-Fen Lee. Spacing Pattern of the Crested Serpent Eagle (Spilornis cheela hoya) in Southern Taiwan (PDF). Taiwania. 2012, 57 (1): 1–13 [2013-02-05]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-12-03).

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Naoroji, R. K.; Monga, S.G. Observations on the Crested Serpent Eagle (Spilornis cheela) in Rajpipla forests – South Gujarat. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1983, 80 (2): 273–285.

- ^ Baker, E.C.S. Some notes on tame Serpent Eagles. The Avicultural Magazine. 1914, 5 (5): 154–159.

- ^ Chia-hong, L. Diurnal activity pattern of Crested Serpent Eagles Spilornis cheela hoya in Kenting, southern Taiwan (学位论文). Taiwan: Graduate Institute of Environment and Ecology. 2010. (原始内容存档于2012-04-02) (Chinese).

- ^ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Cairns, J. The serpent eagles Spilornis cheela of Penang Island, Malaya. Ibis. 1968, 110 (4): 569–571. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1968.tb00064.x.

- ^ Daly, W. M. The southern Indian harrier eagle. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1895, 9 (4): 487.

- ^ Osman, S.M. The Crested Serpent Eagle. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1972, 69 (3): 461–468.

- ^ Hume, A.O. The nests and eggs of Indian birds. Volume 3. London: R.H. Porter. 1890: 152–154.

- ^ Schmidt, G.D.; Kuntz, R.E. Nematode Parasites of Oceanica. XI. Madelinema angelae gen. et sp. n., and Inglisonema mawsonae sp. n. (Heterakoidea: Inglisonematidae) from birds. Journal of Parasitology. 1971, 57 (3): 479–484. JSTOR 3277897. PMID 5104559. doi:10.2307/3277897.

- ^ Yoshino, T.; Shingake, T.; Onuma, M.; Kinjo, T.; Yanai, T.; Fukushi, H.; Kuwana, T.; Asakawa, M. Parasitic helminths and arthropods of the Crested Serpent Eagle Spilornis cheela perplexus Swann, 1922 from the Yaeyama. Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. 2010, 41 (1): 55–61. doi:10.3312/jyio.41.55 .

- ^ Chen C.C., Pei, K.J., Lee, F.R., Tzeng, M.P., Chang, T.C. Avian pox infection in a free-living crested serpent eagle (Spilornis cheela) in southern Taiwan. Avian Dis. 2011, 55 (1): 143–146. PMID 21500652. S2CID 956795. doi:10.1637/9510-082610-Case.1.

- ^ Price, R.D.; Beer, J.R. The Genus Kurodaia (Mallophaga: Menoponidae) from the Falconiformes, with Elevation of the Subgenus Falcomenopon to Generic Rank. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1963, 56 (3): 379–385. doi:10.1093/aesa/56.3.379.

延伸阅读

编辑- BirdLife International. Spilornis cheela. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009. [11 December 2009]. 数据库资料包含解释为何此物种为最低关注

- Birds of India by Grimmett, Inskipp and Inskipp, ISBN 0-691-04910-6