梭狀回

梭狀回(Fusiform gyrus)是顳葉與枕葉一部分,也被稱作枕顳外側回(lateral occipitotemporal gyrus),與枕顳內側回(舌回、海馬旁回)相對應。[1][2][3] 結構上,梭狀回在布羅德曼分區系統為37區,其外側與內側被淺的「梭狀回中間溝(mid-fusiform sulcus)」分開。[4][5][6][7]

| 梭狀回 | |

|---|---|

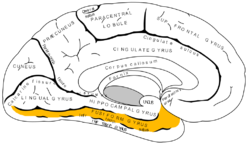

左大腦半球的內側面(梭狀回示意為橙色) | |

右大腦半球的內側面(梭狀回示意為底部的淺綠色) | |

| 標識字符 | |

| 拉丁文 | gyrus fusiformis |

| NeuroNames | 139 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1641 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.227 |

| TA2 | 5500 |

| FMA | FMA:61908 |

| 格雷氏 | p.824 |

| 《神經解剖學術語》 [在維基數據上編輯] | |

結構

編輯梭狀回與下方的顳下回之間有枕顳溝(occipitotemporal sulcus)相隔開,與上方的海馬旁回、舌回之間有側副裂隔開[1][2][8]。

功能

編輯科學界對梭狀回功能有下述比較一致的認識:

研究表明,梭狀回與臉盲症,即面部辨識能力缺乏症,直接相關。[9]梭狀回中負責人臉認知的部分稱為梭狀回面孔區(fusiform face area, FFA)。梭狀回面孔區可以對不是臉的視覺形象產生像臉的認知,著名的例子如火星上的利比亞山與塞東尼亞區。如果梭狀回面孔區被破壞,就會失去辨識人臉的能力,就連最親密的家人也無法認出來。眼睛負責感知視覺信息,經過視皮層處理後,再由梭狀回辨析,找出生物特徵,藉此來分辨不同的人。梭狀回面孔區中的內梭狀回在接收到人臉信息時被激活,而且在害羞的人與善於社交的人的內梭狀回表現不同。一項研究證實查看陌生人的圖像時,害羞的成年人內梭狀回活化的程度比善於社交的成年人顯着地少。[10]除此之外,另一項研究指出觀看到吸引人的臉孔時內梭狀回活化的程度會更高,主因為美麗的容貌喚起廣泛的神經網絡,包括知覺、獎勵、決策等迴路。[11]

梭狀體異常與威廉氏症候群相關。[12] 梭狀體也與表情的認知有關。[13]自閉症的人在看到人臉時,其梭狀體很少甚至沒有興奮活動。[14]

梭狀回面孔區增加活動程度可產生人臉幻覺,可能是真實人臉或者卡通人臉。這見於邦納症候群, 睡前幻覺、 大腦腳性幻覺症、藥物導致的幻覺等。[15]

有研究表明,汽車專家在辨識汽車圖片時、鳥類專家在辨識鳥的圖片時,梭狀回面孔區的活動程度很高。因此,提出了這樣的問題:梭狀回面孔區在辨識人臉時被激活,是因為人類進化的結果還是該受試者具有辨識人臉的專業知識?心理學家用一類物體稱為greebles來檢驗上述兩個衝突的假設。[16] 當受試者初次看到greebles,其梭狀回面孔區的興奮程度遠低於看到人臉的時候。受試者熟悉了greebles或者說變成了greeble專家,其梭狀回面孔區在看到人連與greeble的興奮程度相當。類似地,自閉症兒童在與人臉識別相同部位產生受損的對象識別。[17] 後續研究表明自閉症患者的梭狀回面孔區具有很低的神經元密度。[18]這產生如下問題:較少的神經元導致了不良的人臉認知,還是自閉症患者很少的人臉感知導致了神經元數量的下降?[19]更簡單的問題是:人臉是每個人都具有專業識別知識的對象? -

有證據表明梭狀回面孔區中負責人臉識別的區域的功能是進化而得。其他研究發現了人腦中專門負責識別所處環境與身體的區域。[20][21] 對漢字識別的研究表明,對應的梭狀回面孔區中具有很高興奮的區域與響應人臉識別的區域不同。[22]這意味着梭狀回面孔區中的特定區域進化成專責人臉識別功能。

在具有字形→顏色聯覺症的人當中,發現了梭狀回的活動。[23]

MIT的一項研究表明,左、右梭狀回在認知中具有不同的角色,隨後二者又會互聯。左梭狀回負責識別類似於人臉的視覺對象的特徵,而右梭狀回負責確定這些被識別出來的類似人臉的視覺對象是否真是人臉。[24]

圖片

編輯-

梭狀回動畫

-

梭狀回下面觀

-

梭狀回的腹面觀(自底向上)示意圖

-

梭狀回的腹面觀(自底向上)

參考文獻

編輯- ^ 1.0 1.1 Fusiform gyrus. 華盛頓大學. [2021-05-31]. (原始內容存檔於2021-06-03) (英語).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Loh, Daniel. Fusiform gyrus. Radiopaedia. [2021-05-31]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-04) (美國英語).

- ^ Nature Neuroscience, vol7, 2004

- ^ Weiner et al. The mid-fusiform sulcus: A landmark identifying both cyotarchitectonic and functional divisions of human ventral temporal cortex. NeuroImage. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.068

- ^ Weiner & Grill-Spector, Sparsely-distributed organization of face and limb activations in human ventral temporal cortex. NeuroImage. 2010 Oct 1;52(4):1559-73. Epub 2010 May 10.

- ^ Nasr el al. Scene-selective cortical regions in human and nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2011 Sep 28;31(39):13771-85.

- ^ Gyrus. The free dictionary. [2013-06-19]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-20).

- ^ Gaillard, Frank. Medial occipitotemporal gyrus. Radiopaedia. [2021-05-31]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-05) (美國英語).

- ^ McCarthy, G et al. Face-specific processing in the fuman fusform gyrus.J. Cognitive Neuroscicence. 9, 605-610(1997).

- ^ Beaton, E. A., Schmidt, L. A., Schulkin, J., Antony, M. M., Swinson, R. P. & Hall, G. B. Different fusiform activity to stranger and personally familiar faces in shy and social adults. Social Neuroscience. 2009, 4 (4): 308–316. PMID 19322727. doi:10.1080/17470910902801021.

- ^ Chatterjee, A., Thomas, A., Smith, S. E., & Aguirre, G. K. The neural response to facial attractiveness. Neuropsychology. 2009, 23 (2): 135–143. PMID 19254086. doi:10.1037/a0014430.

- ^ A. L. Reiss, et al. Preliminary Evidence Of Abnormal White Matter Related To The Fusiform Gyrus In Williams Syndrome: A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography Study.Genes, Brain & Behavior 11.1, 62-68(2012)

- ^ Radua, Joaquim; Phillips, Mary L.; Russell, Tamara; Lawrence, Natalia; Marshall, Nicolette; Kalidindi, Sridevi; El-Hage, Wissam; McDonald, Colm; Giampietro, Vincent. Neural response to specific components of fearful faces in healthy and schizophrenic adults. NeuroImage. 2010, 49 (1): 939–946. PMID 19699306. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.030.

- ^ Carter, Rita. The Human Brain Book. : 241.

- ^ Jan Dirk Blom. A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer, 2010, p. 187. ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0

- ^ Gauthier, I; Behrmann M Tarr MJ. Can Face Recognition Really be Dissociated from Object Recognition?. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1999, 11 (4): 349–70. PMID 10471845. doi:10.1162/089892999563472.

- ^ Scherf, S; Behrmann M Minshew N Luna B. Atypical Development of Face and Greeble Recognition in Autism. Journal of Child Psychiatry. April 2008, 49 (8): 838–47. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01903.x.

- ^ van Kooten, IA; Palmen SJ; von Cappeln P; Steinbusch HW; Korr H; Heinsen H; Hof PR; van Engeland H; Schmitz C. Neurons in the Fusiform Gyrus are Fewer and Smaller in Autism. Brain. April 2008, 131 (4): 987–99. doi:10.1093/brain/awn033.

- ^ Gazzaniga, Michael. Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the Mind. New York City: W.W. Norton Company Inc. 2014: 247. ISBN 978-0393603170.

- ^ Epstein, Russell; Kanwisher, Nancy. A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Nature. April 1998, 392 (6676): 598–601. PMID 9560155. doi:10.1038/33402.

- ^ Downing, Paul; Yuhong Jiang; Miles Shuman; Nancy Kanwisher. A Cortical Area Selective for Visual Processing of the Human Body. Science. September 2001, 293 (5539): 2470–2473. PMID 11577239. doi:10.1126/science.1063414.

- ^ Fu, S; Chunliang F; Shichun G; Yuejia L; Raja P. Barton, Jason Jeremy Sinclair , 編. Neural Adaptation Provides Evidence for Categorical Differences in Processing of Faces and Chinese Characters: an ERP Study of the N170. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (7): e41103. PMC 3404057 . PMID 22911750. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041103.

- ^ Imaging of connectivity in the synaesthetic brain « Neurophilosophy. [2014-03-17]. (原始內容存檔於2014-03-17).

- ^ Trafton, A. "How does our brain know what is a face and what’s not?" MIT News. [2014-03-17]. (原始內容存檔於2014-03-17).

外部連結

編輯- Location (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) at mattababy.org

- "VS Ramachandran on your mind" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) at ted.com

- "Oliver Sacks: What hallucination reveals about our minds" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) at ted.com

- NIF Search - Fusiform Gyrus[失效連結] via the Neuroscience Information Framework