北极理事会

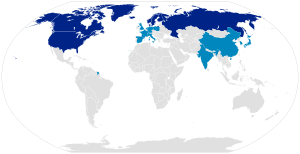

北极理事会(英语:The Arctic Council、俄语:Арктический совет),又译为北极议会、北极委员会、北极协会,是一个高层次国际论坛,关注邻近北极的政府和原住民所面对的问题。总部设于挪威特罗姆瑟。目前组织有八个成员国,分别为:加拿大、美国、俄罗斯、冰岛、挪威、丹麦、瑞典、芬兰。[1]

| |

成员国

观察员国

| |

| 成立时间 | 1996年9月19日 |

|---|---|

| 创始地 | 渥太华 |

| 类型 | 政府间组织 |

| 总部 | 挪威特罗姆瑟(自2012年) |

会员 | |

| 目标 | 论坛性质,推进各环北极国家的合作与互动,同时涉及北极圈内的本土民族 |

| 网站 | arctic-council.org |

历史

编辑创立北极理事会的第一步是在1991年由八个邻近北极的政府所签署的北极环境保护策略。在1996年,《渥太华宣言》[2]标志着理事会的成立,[3]成为北极国家政府之间合作的论坛,涉及北极土著民族事务、可持续发展和环境保护。[4][5]北极理事会还从事气候变迁、化石燃料和北极航船的研究。[6][7][5][8]

2011年,理事会成员国通过北极搜索和营救协定,成为该组织第一份有法律效力的协议。[9][10][5][7]

2022年3月3日,因2022年俄罗斯入侵乌克兰事件,除俄罗斯以外的7个成员国紧急通过视讯会议,宣布在俄罗斯作为理事会主席国期间,不参加剩余会议。[11][12]2022年6月8日,这7国发表另一份声明,将在没有俄罗斯参与的情况下,逐步恢复基于该理事会此前提出的项目和议定书的工作。[13][14]

会籍

编辑成员

编辑按照规定,只有有部分领土位于北极圈内的国家方可成为正式成员,现在北极理事会的成员有:[15]

观察员

编辑北极理事会设置观察员席,对非北极国家开放,由每两年举办一次的部长会议所决定。2011年,理事会公布观察员的加入资格,当中包括需要承认北极国家在北极地区的主权和治权,认可建设北冰洋法律框架(例如海洋法)。[5]观察员无投票权。截至2021年,共有13个非北极国家获观察员地位。[16]观察员通常会受邀参加理事会的绝大部分会议,虽然部分非北极国家希望能够加入一些深部的内部活动,但观察员并非一定能够参加某些项目和任务。

- 1998年加入:

- 2000年加入:

- 2006年加入

- 2013年5月15日,在瑞典北部城市基律纳召开的北极理事会第八次部长级会议上,以下国家加入:[17]

- 2017年5月11日,在美国阿拉斯加州费尔班克斯召开的第十次部长级会议上,以下国家加入:[18]

待定观察员

编辑待定观察员为已经通过大部分参加条件的候选国。2013年基律纳大会上,欧盟提出了加入要求。但由于部分欧盟国家禁止猎杀海豹,故请求暂未被通过。[19]

目前的待定观察员有

待定观察员和永久观察员的分别是,永久观察员会自动获邀出席所有会议(虽然它们未必会全部参与),待定观察员出席每一次会议都需要批准(虽然批准已属例行形式)。

北极原住民族参与组织

编辑在八个正式成员国当中,有七个拥有数量可观的原住民族,冰岛是唯一没有原住民族居住的成员国。所有北极原住民族组织均可获永久参与员地位,[5]但需满足以下任一条件:代表世居在多于一个北极国家的某一原著民族,或代表某一北极国家内,两个或多于两个以上的世居原住民族。原住民族参与组织的数量需要在任何时候都小于正式成员国的数量。原住民族参与组织能够参加理事会的一切活动。

截至2021年,共有六个北极原住民族参与组织:

- 阿留申国际协会:代表俄罗斯和美国阿拉斯加内的阿留申人(约有1万5000人)[22]

- 北极阿萨巴斯卡议会:代表加拿大内(西北地区和育空)和美国阿拉斯加内使用阿萨巴斯卡人(约有4万5000人)[23]

- 哥威迅国际议会:代表加拿大内(西北地区和育空)和美国阿拉斯加内的哥威迅人(约有9000人)[24]

- 因纽特北极圈议会:代表加拿大、格陵兰岛、俄罗斯楚科奇自治区和美国阿拉斯加内的因纽特人(约有18万人)[25]

- 俄罗斯北方原住民族协会:代表居住在俄罗斯西伯利亚、远东地区和极北地区的北方原住民(约有25万人)[26]

- 萨米理事会:代表芬兰、挪威、瑞典和俄罗斯内的萨米人(约有10万人)[27]

以上组织由北极理事会原住民秘书处管理。[28]

观察组织

编辑北极理事会同时也对政府间组织、议会间组织和非政府组织开放,并对其授予观察组织地位。[29]目前有以下观察组织:极地区议员会议[30]、国际自然保护联盟、国际红十字会、北欧理事会、北方论坛[31]、联合国开发计划署、联合国环境署、世界驯鹿牧民协会[32]、北极大学、世界自然基金会北极规划小组。

行政

编辑会议

编辑北极理事会每六个月在主席国家召开一次资深北极官员会议。资深北极官员是八个成员国的高层代表,通常为外交官或其他高阶外交部官员。会议同时邀请六个原住民族组织及观察员的代表。

在两年任期结束之前,轮任主席会召开部长级会议,对其任内的工作作到任总结。与会者一般为成员八个成员国的外交部、北方事务部或环境部部长。

每次部长级会议都有以当地城市为名的宣言。该宣言会归纳理事会过去的成就和对未来的展望,一般会涵盖气候改变、可持续发展、北极监督和评估、北极永久生物污染物及其他污染物等主要议题,还有六个工作小组的工作总结。

以下为过去各部长级会议列表:

| 日期 | 城市 | 国家 |

|---|---|---|

| 1998年9月17至18日 | 伊魁特 | 加拿大 |

| 2000年10月13日 | 乌特恰维克 | 美国 |

| 2002年10月10日 | 伊纳里 | 芬兰 |

| 2004年11月24日 | 雷克雅维克 | 冰岛 |

| 2006年10月26日 | 萨列哈尔德 | 俄罗斯 |

| 2009年4月29日 | 特罗姆瑟 | 挪威 |

| 2011年5月12日 | 努克 | 丹麦格陵兰岛 |

| 2013年5月15日 | 基律纳 | 瑞典 |

| 2015年4月24日 | 伊魁特 | 加拿大 |

| 2017年5月10至11日 | 费尔班克斯 | 美国 |

| 2019年5月7日 | 罗瓦涅米 | 芬兰 |

| 2021年5月19至20日 | 雷克雅维克 | 冰岛 |

轮任主席国

编辑理事会每两年更换一次主席国。[33]目前主席国为俄罗斯,其任期至2023年。[34]

以下为理事会历史上的轮任主席国:

- 加拿大(1996-1998年)[35]

- 美国(1998-2000年)[36]

- 芬兰(2000-2002年)[37]

- 冰岛(2002-2004年)[38]

- 俄罗斯(2004-2006年)[39]

- 挪威(2006-2009年)[40]

- 丹麦(2009-2011年)[41][42]

- 瑞典(2011-2013年)[43][44]

- 加拿大(2013-2015年)[45]

- 美国(2015-2017年)[46]

- 芬兰(2017-2019年)[47][48]

- 冰岛(2019-2021年)

- 俄罗斯(2021-2023年)

- 挪威(2023-2025年)

秘书处

编辑每任主席国负责理事会秘书处的运行。秘书处负责处理理事会的行政事务,其职责包括,组织半年会议、管理议会网站以及分发报告和文件。由于三个北欧国家挪威、丹麦和瑞典达成一致意见共享秘书处,[49]挪威北极学院曾于2007年至2013年连续六年间承担秘书处工作,工作人员亦来自以上三国。

部分成员国希望建立常设秘书处,但美国自北极理事会成立开始就一直否决这建议。最终在2012年,理事会决定在挪威特罗姆瑟设立常任秘书处。[50][5]

北极理事会原住民秘书处

编辑对于六个原住民组织而言,若每次理事会召开会议都派出代表与会(尤其会议地点会在各北极城市间变动),将会对其组成较大的财政负担。为解决其囧景,同时鼓励原住民组织积极参与理事会的工作,理事会对原住民秘书处提供财政支持。[51]

工作小组

编辑北极理事会的实际工作是由辖下的六个工作小组负责

- 北极监督和评估计划[52](英文:Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme,缩写 AMAP)

- 北极理事会控污行动计划[53](英文:Arctic Contaminants Action Program,缩写 ACAP)

- 北极动植物保育[54](英文:Conservation of Arctic Flora & Fauna,缩写 CAFF)

- 紧急、预防、准备暨应变[55](英文:Emergency Prevention, Preparedness & Response,缩写 EPPR)

- 北极海洋环境保护[56][57](英文:Protection of the Arctic Marine Environmen,缩写 PAME)

- 可持续发展工作组 [58](英文:Sustainable Development Working Group,缩写 SDWG)

规划和行动计划

- 北极气候冲击评估

- 北极人类发展报告

- 北极生物多样性评估

- 环北极生物多样性监控计划

安全与地缘政治

编辑1996年北极理事会成立之际,《渥太华宣言》中有一项脚注表明“北极理事会不应涉及军事安全领域”。[59]但在2019年,美国国务卿迈克·蓬佩奥指出,当前的形势已经不同以往,北极地区成为各方力量角力的舞台,理事会需要适应该未来趋势。[60]

但总体而言,北极地区的领土争端通常相当有限。最突出的例子有围绕汉斯岛(丹麦和加拿大之间)和波弗特海(美国和加拿大之间)的争端。[61][62]

该地区的领土纷争,大多数是想争夺北冰洋下海床的专有权。由于气候变化及北冰洋浮冰及冻土加速融化,很多之前无法开采的能源和无法使用的航道如今纷纷变得有利可图。根据《联合国海洋法公约》,各国可将从测算领海宽度的基线量起,不应超过二百海里(370.4公里)内的水体宣示为专属经济区,并对该范围内的自然资源拥有专有权,但加拿大、俄罗斯以及丹麦(格陵兰岛)三国却对联合国大陆架界限委员会(UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf)提交了互相重叠的权力宣称范围。一旦大陆架界限委员会作出裁决,三国需开启谈判以分割重叠宣称的范围。[63]

- 加拿大将整条西北水道纳为自己的内海范围内,意味着加拿大能够自由控制水道上通行的船只。而美国则认为,西北水道是国际水道,任何船只在任何时候都有权通行,且加方不得关闭水道。加拿大公众对西北水道的主权问题亦相当关注,且根据民意调查,半数加国公民希望政府能够尝试去维护本国对水道的主权,而对比之下,美国则仅有10%的居民对政府有类似要求。[64]

- 以北方海路的争端则不一样。俄罗斯仅将海路上一些海峡附近的领域纳为自身的内海范围,但俄罗斯同时亦要求各商业船只需先得俄方批准,方可进入俄罗斯的专属经济区。

随着理事会逐渐接纳更多的观察员,后者亦开始表达对北极地区的兴趣。中国已经公开表示希望能够开采格陵兰岛的自然资源。[65]

在军事方面上,加拿大、丹麦、挪威和俄罗斯都纷纷加强北极地区内的军事基础设施建设。[66]

虽然各成员国间稍有冲突,但仍有人表示乐观,认为理事会可以加强地区稳定。[5]挪威海军上将哈康·布鲁恩·汉森就曾指出,“北极地区可能是全世界最稳定的地区”。北极地区亦有健全的立法和有效的执法。[67]各成员一致达成共识,只有建立良好合作关系,共同承担对北极地区的研究、航道开发等任务,才能够惠泽所有相关方。[68]

近年来,亦有部分评论称北极理事会需要开始涉足地区安全和和平方面的事务。2010年的一份问卷调查显示,大部分挪威、加拿大、芬兰、冰岛和丹麦的受访者希望将北极纳为无核武地带。[69]而俄罗斯的受访者则只有少部分有类似诉求,但当中依然有80%的受访者表示理事会需要开始领导地区的和平建设。[70]但直至2014年6月,理事会依然继续回避军事安全方面的议题。[71]

参见

编辑脚注

编辑- ^ About the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Arctic Council: Founding Documents. Arctic Council Document Archive. [2013-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-02).

- ^ Axworthy, Thomas S. Canada bypasses key players in Arctic meeting. The Toronto Star. March 29, 2010 [2013-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Savage, Luiza Ch. Why everyone wants a piece of the Arctic. Maclean's. Rogers Digital Media. May 13, 2013 [2013-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-05).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Buixadé Farré, Albert; Stephenson, Scott R.; Chen, Linling; Czub, Michael; Dai, Ying; Demchev, Denis; Efimov, Yaroslav; Graczyk, Piotr; Grythe, Henrik; Keil, Kathrin; Kivekäs, Niku; Kumar, Naresh; Liu, Nengye; Matelenok, Igor; Myksvoll, Mari; O'Leary, Derek; Olsen, Julia; Pavithran .A.P., Sachin; Petersen, Edward; Raspotnik, Andreas; Ryzhov, Ivan; Solski, Jan; Suo, Lingling; Troein, Caroline; Valeeva, Vilena; van Rijckevorsel, Jaap; Wighting, Jonathan. Commercial Arctic shipping through the Northeast Passage: Routes, resources, governance, technology, and infrastructure. Polar Geography. October 16, 2014, 37 (4): 298–324. doi:10.1080/1088937X.2014.965769 .

- ^ About the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Lawson W Brigham. Think Again: The Arctic. Foreign Policy. September–October 2021 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-13).

- ^ Brigham, L.; McCalla, R.; Cunningham, E.; Barr, W.; VanderZwaag, D.; Chircop, A.; Santos-Pedro, V.M.; MacDonald, R.; Harder, S.; Ellis, B.; Snyder, J.; Huntington, H.; Skjoldal, H.; Gold, M.; Williams, M.; Wojhan, T.; Williams, M.; Falkingham, J. Brigham, Lawson; Santos-Pedro, V.M.; Juurmaa, K. , 编. Arctic marine shipping assessment (AMSA) (PDF). Norway: Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME), Arctic Council. 2009. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于January 28, 2016).

- ^ About the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Lawson W Brigham. Think Again: The Arctic. Foreign Policy. September–October 2021 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-13).

- ^ Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation following Russia's Invasion of Ukraine. 3 March 2022 [3 March 2022]. (原始内容存档于2022-06-04).

- ^ Canada, six other states pull back from Arctic Council in protest over Ukraine. ctvnews.ca. 3 March 2022. (原始内容存档于3 March 2022).

- ^ Canada, Global Affairs. Joint statement on limited resumption of Arctic Council cooperation. www.canada.ca. 2022-06-08 [2022-07-24]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-30).

- ^ Schreiber, Melody. Arctic Council nations to resume limited cooperation — without Russia. ArcticToday. 2022-06-08 [2022-07-24]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-30) (美国英语).

- ^ About the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Observers. Arctic Council Secretariat (2021). Arctic Council. [September 15, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ 中国成为北极理事会正式观察员. [2013-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-24).

- ^ ARCTIC COUNCIL MINISTERS MEET, SIGN BINDING AGREEMENT ON SCIENCE COOPERATION, PASS CHAIRMANSHIP FROM U.S. TO FINLAND. [2020-03-10]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-12).

- ^ The EU and the Arctic Council. (原始内容存档于November 17, 2018).

- ^ Observers. Arctic Council Secretariat (2021). Arctic Council. [September 15, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Turkey raises profile to be a polar power with expeditions. Daily Sabah. May 21, 2020 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Aleut International Association. Arctic Council. [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Arctic Athabaskan Council. Arctic Council. [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Gwich'in Council International. Arctic Council. [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Gwich'in Council International. Arctic Council. [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North. Arctic Council. [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Saami Council. Arctic Council. [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ About the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Observers. Arctic Council Secretariat (2021). Arctic Council. [September 15, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-29).

- ^ Arctic Parliamentarians. Arcticparl.org. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-21).

- ^ Northern Forum. Northern Forum. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2017-11-08).

- ^ Association of World Reindeer Herders. (原始内容存档于September 28, 2007).

- ^ Troniak, Shauna. Canada as Chair of the Arctic Council. HillNotes. Library of Parliament Research Publications. May 1, 2013 [2013-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-29).

- ^ Iceland Chairs Arctic Council. [2019-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-25).

- ^ Canadian Chairmanship Program 2013–2015. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2019-11-15) (英国英语).

- ^ Secretary Tillerson Chairs 10th Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting. U.S. Department of State. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-11) (美国英语).

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03) (英国英语).

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03) (英国英语).

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03) (英国英语).

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03) (英国英语).

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03) (英国英语).

- ^ The Kingdom of Denmark. Chairmanship of the Arctic Council 2009–2011. Arctic Council. 2009-04-29 [2021-12-31]. (原始内容存档于2021-12-31) (英语).

- ^ Troniak, Shauna. Canada as Chair of the Arctic Council. HillNotes. Library of Parliament Research Publications. May 1, 2013 [2013-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-29).

- ^ Council of American Ambassadors. Council of American Ambassadors. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Category: About. The Norwegian, Danish, Swedish common objectives for their Arctic Council chairmanships 2006–2013. Arctic Council. 2011-04-07 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-27).

- ^ Secretary Tillerson Chairs 10th Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting. U.S. Department of State. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-11) (美国英语).

- ^ The Arctic Council. Arctic Council. [2020-03-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-23).

- ^ Finland's Chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2017–2019. Ministry for Foreign Affairs. [2021-12-31]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-21).

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat. Arctic Council. [2018-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03) (英国英语).

- ^ Travel of Deputy Secretary Burns to Sweden and Estonia. State.gov. 2012-05-14 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Terms, Reference and Guidelines (PDF). (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-20).

- ^ Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme. Amap.no. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2006-10-22).

- ^ Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP). Acap.arctic-council.org. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-28).

- ^ Conservation of Arctic Flora & Fauna (CAFF). Caff.is. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2006-11-26).

- ^ Emergency Prevention, Preparedness & Response. Eppr.arctic-council.org. 2013-06-04 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2007-03-11).

- ^ Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment. Pame.is. 2013-06-13 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2006-12-09).

- ^ User, Super. Oops! We couldn't find this page for you. Arctic Portal. [2021-12-31]. (原始内容存档于2022-06-01).

- ^ Sustainable Development Working Group. Portal.sdwg.org. 2013-08-27 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-14).

- ^ Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council (Ottawa, Canada, 1996). May 10, 2017 [September 17, 2021]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-04).

- ^ Dams, Ties; van Schaik, Louise; Stoetman, Adája. Presence before power: why China became a near-Arctic state (报告). Clingendael Institute: 6–19. 2020. JSTOR resrep24677.5 .

- ^ Transnational Issues CIA World Fact Book. CIA. [2012-01-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-21).

- ^ Sea Changes. (原始内容存档于June 13, 2007).

- ^ Overfield, Cornell. An Off-the-Shelf Guide to Extended Continental Shelves and the Arctic. Lawfare. [2021-08-07]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Jill Mahoney. Canadians rank Arctic sovereignty as top foreign-policy priority. The Globe and Mail. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Outsiders in the Arctic: The roar of ice cracking. The Economist. 2013-02-02 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2019-11-04).

- ^ The Arctic: Five Critical Security Challenges | ASPAmerican Security Project. Americansecurityproject.org. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-27).

- ^ Outsiders in the Arctic: The roar of ice cracking. The Economist. 2013-02-02 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2019-11-04).

- ^ Arctic politics: Cosy amid the thaw. The Economist. 2012-03-24 [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-03).

- ^ Rethinking theTop of the World: Arctic Security Public Opinion Survey (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), EKOS, January 2011

- ^ Janice Gross Stein And Thomas S. Axworthy. The Arctic Council is the best way for Canada to resolve its territorial disputes. The Globe and Mail. [2013-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21).

- ^ Berkman, Paul. Stability and Peace in the Arctic Ocean through Science Diplomacy. Science & Diplomacy. 2014-06-23, 3 (2) [2022-01-01]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-26).