叶绿体DNA

叶绿体DNA(Chloroplast DNA,cpDNA)为真核生物细胞中叶绿体内的DNA。叶绿体等质粒体中具有一独立于细胞核的基因组,且含有核糖体可转译合成自身的蛋白质[1][2],为一半自主的胞器,叶绿体DNA最早于1959年透过生化实验发现[3],并于1962年透过电子显微镜实际观测确认[4]。1986年烟草与地钱的叶绿体DNA被定序发表,为最早完成定序的叶绿体基因组[5][6],目前已有大量陆生植物与藻类的质粒体被定序发表。

基因组结构

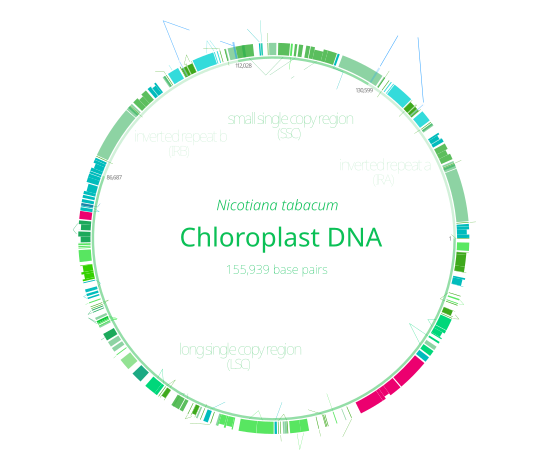

编辑叶绿体DNA为环状,长度一般介于120至170kb之间[7][8][9],分子量为8000万至1.3亿Da[10],多数植物的叶绿体包含约120个基因[11][12],大多编码光合作用所需的蛋白(包括RuBisCO的大次单元)与基因表现所需的蛋白[13],如4种rRNA、约30种tRNA、21种核糖体蛋白以及叶绿体RNA聚合酶的4个次单元[13]。绝大多数生物的叶绿体DNA均不分段,双鞭毛虫门的藻类则为罕见例外,此类生物的叶绿体DNA包括约40段质体,每个质体长2至10kb,包含1至3个基因,也有些质体不编码任何基因[14]。

多数叶绿体DNA包括两段反向重复序列(IRa与IRb),将叶绿体DNA分成大单拷贝区(LSC)与小单拷贝区(SSC)两区域[9]。反向重复序列长4至25kb,其中植物的一般在20至25kb之间[15],IRa与IRb的序列一般会因协同演化而非常近似[14]。植物叶绿体DNA的反向重复序列演化上相当保守[9][15],蓝菌基因组与灰藻和红藻的叶绿体基因组中也有与其同源的序列,显示此序列在演化上的起源很早,在叶绿体出现前即已存在[14]。有些叶绿体(豌豆与数种红藻[14])的基因组丢失了反向重复序列[15][16],紫菜属红藻叶绿体则有一个重复序列发生了倒转,使IRa与IRb变为同向排列[14]。反向重复序列可能可帮助维持叶绿体DNA的稳定[16]。

陆生植物新叶的叶绿体中一般有约100个叶绿体DNA,老叶中则仅剩15至20个[17],多包裹成拟核,一个叶绿体中常有数个拟核[10]。叶绿体DNA虽不与组蛋白结合[18],但红藻的叶绿体DNA可编码和组蛋白相似的组蛋白样叶绿体蛋白(HC)与自身结合[19]。较原始的红藻Cyanidioschyzon merolae(属温泉红藻纲)的叶绿体拟核集中在叶绿体基質的中央,绿藻与陆生植物的叶绿体拟核则均匀分布于基質中[19]。

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ Lyttleton, J. W. Isolation of ribosomes from spinach chloroplasts. Exp. Cell Res. 1962, 26 (1): 312–317. PMID 14467684. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(62)90183-0.

- ^ Heber, U. Protein synthesis in chloroplasts during photosynthesis. Nature. 1962, 195 (1): 91–92. Bibcode:1962Natur.195...91H. PMID 13905812. S2CID 4265095. doi:10.1038/195091a0.

- ^ Stocking, C. R.; Gifford, E. M. Incorporation of thymidine into chloroplasts of Spirogyra. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1959, 1 (3): 159–164. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(59)90010-5.

- ^ Ris, H.; Plaut, W. Ultrastructure of DNA-containing areas in the chloroplast of Chlamydomonas. J. Cell Biol. 1962, 13 (3): 383–91. PMC 2106071 . PMID 14492436. doi:10.1083/jcb.13.3.383.

- ^ Shinozaki, K.; Ohme, M.; Tanaka, M.; Wakasugi, T.; Hayashida, N.; Matsubayashi, T.; Zaita, N.; Chunwongse, J.; Obokata, J.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Ohto, C. The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: its gene organization and expression. The EMBO Journal. 1986, 5 (9): 2043–2049. ISSN 0261-4189. PMC 1167080 . PMID 16453699. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04464.x.

- ^ Ohyama, Kanji; Fukuzawa, Hideya; Kohchi, Takayuki; Shirai, Hiromasa; Sano, Tohru; Sano, Satoshi; Umesono, Kazuhiko; Shiki, Yasuhiko; Takeuchi, Masayuki; Chang, Zhen; Aota, Shin-ichi. Chloroplast gene organization deduced from complete sequence of liverwort Marchantia polymorpha chloroplast DNA. Nature. 1986, 322 (6079): 572–574 [2022-01-17]. Bibcode:1986Natur.322..572O. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4311952. doi:10.1038/322572a0. (原始内容存档于2022-08-02).

- ^ Dann, Leighton. Bioscience—Explained (PDF). Green DNA: BIOSCIENCE EXPLAINED. 2002 [2022-01-17]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-09-17).

- ^ Clegg MT, Gaut BS, Learn GH, Morton BR. Rates and patterns of chloroplast DNA evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994, 91 (15): 6795–801. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6795C. PMC 44285 . PMID 8041699. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.15.6795 .

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Shaw J, Lickey EB, Schilling EE, Small RL. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. American Journal of Botany. March 2007, 94 (3): 275–88. PMID 21636401. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.3.275.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Burgess, Jeremy. An introduction to plant cell development. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. 1989: 62. ISBN 978-0-521-31611-8.

- ^ Daniell, H.; Lin, C.; Yu, M.; Chang, W. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016, 17 (1): 134. PMC 4918201 . PMID 27339192. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2.

- ^ Clegg, M. T.; Gaut, B. S.; Learn, G. H.; Morton, B. R. Rates and patterns of chloroplast DNA evolution. PNAS. 1994, 91 (15): 6795–6801. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6795C. PMC 44285 . PMID 8041699. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.15.6795 .

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Berry, J. O.; Yerramsetty, P.; Zielinski, A. M.; Mure, C. M. Photosynthetic gene expression in higher plants. Photosynth. Res. 2013, 117 (1): 91–120. PMID 23839301. S2CID 16536768. doi:10.1007/s11120-013-9880-8.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Sandelius, Anna Stina. The Chloroplast: Interactions with the Environment. Springer. 2009: 18. ISBN 978-3-540-68696-5.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Kolodner R, Tewari KK. Inverted repeats in chloroplast DNA from higher plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. January 1979, 76 (1): 41–5. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76...41K. PMC 382872 . PMID 16592612. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.1.41 .

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Palmer JD, Thompson WF. Chloroplast DNA rearrangements are more frequent when a large inverted repeat sequence is lost. Cell. 1982, 29 (2): 537–50. PMID 6288261. S2CID 11571695. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90170-2.

- ^ Plant Biochemistry 3rd. Academic Press. 2005: 517. ISBN 9780120883912.

number of copies of ctDNA per chloroplast.

- ^ Biology 8th Edition Campbell & Reece. Benjamin Cummings (Pearson). 2009: 516.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Kobayashi T, Takahara M, Miyagishima SY, Kuroiwa H, Sasaki N, Ohta N, Matsuzaki M, Kuroiwa T. Detection and localization of a chloroplast-encoded HU-like protein that organizes chloroplast nucleoids. The Plant Cell. July 2002, 14 (7): 1579–89. PMC 150708 . PMID 12119376. doi:10.1105/tpc.002717.