驕傲旗

驕傲旗(英語:Pride flag)是代表LGBTQ的一部分的任何旗幟,「驕傲」一詞指的是同志驕傲的概念,這個術語與「同志旗」和「酷兒旗」經常互換使用。[1]

驕傲旗可以代表各種性取向、戀愛傾向、性別認同、酷兒文化、區域及整個LGBTQ社區,有些驕傲旗並非專門與LGBTQ相關,例如:皮革自豪之旗。代表整個LGBTQ社區的彩虹旗,是使用最廣泛的其中一種驕傲旗。

許多社區採用不同的旗幟,其中大多數都從彩虹旗中汲取靈感。這些旗幟通常由業餘設計師設計,並在網絡或附屬組織中逐漸受到關注,最終成為社區的象徵性代表,取得半官方的地位。通常這些旗幟包含多種顏色,象徵着包容相關社區的不同特性。

樣例

編輯彩虹

編輯Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow pride flag for the 1978 San Francisco Gay Freedom Day celebration.[2] The flag was designed as a "symbol of hope" and liberation, and an alternative to the symbolism of the pink triangle.[3] The flag does not depict an actual rainbow. Rather, the colors of the rainbow are displayed as horizontal stripes, with red at the top and violet at the bottom. It represents the diversity of gays and lesbians around the world. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony, and violet for spirit.[4] A copy of the original 20-by-30 foot, eight-color flag was made by Baker in 2000 and was installed in the Castro district in San Francisco.[5] Many variations on the rainbow flag exist, including ones incorporating other LGBTQ symbols like the triangle or lambda.[6] In 2018, designer Daniel Quasar created a modified version of the rainbow pride flag, incorporating elements of other flags to bring focus on inclusion and progress. This flag is known as the Progress Pride Flag. In 2021, Valentino Vecchietti of Intersex Equality Rights UK redesigned the Progress Pride Flag to incorporate the intersex flag.[7][8]

-

Original eight-stripe version designed by Gilbert Baker (1978)

-

Seven-stripe version with hot pink color removed due to a lack of fabric (1978–1979)

-

Six-stripe version with turquoise color removed and indigo color changed to royal blue (1979–present)

-

Daniel Quasar's Progress variant of the rainbow pride flag (2018–present)

-

Valentino Vecchietti's intersex-inclusive Progress Pride Flag (2021–present)

-

Double-sided Progress pride flag, including bisexual colours (2024–present)

無浪漫傾向

編輯

The aromantic pride flag consists of five horizontal stripes, which are (from top to bottom) green, light green, white, gray, and black. The flag was created by Cameron Whimsy[9] in 2014.[10] The green and light green stripes represent aromanticism and the aro-spectrum. The white stripe represents the importance and validity of non-romantic forms of love, which include friendship, platonic and aesthetic attraction, queerplatonic relationships, and family. The black and gray stripes represent the sexuality spectrum, which ranges from aro-aces (aromantic asexuals) to aromantic allosexuals.[9][10]

無性戀

編輯

The asexual pride flag consists of four horizontal stripes: black, gray, white, and purple from top to bottom.[11][12][頁碼請求] The flag was created by an Asexual Visibility and Education Network user standup in August 2010, as part of a community effort to create and choose a flag.[13][14] The black stripe represents asexuality; the gray stripe represents gray-asexuals and demisexuals; the white stripe represents allies; and the purple stripe represents community.[15][16]

雙性戀

編輯

Introduced on December 5, 1998,[17] the bisexual pride flag was designed by activist Michael Page to represent and increase the visibility of bisexual people in the LGBTQ community and society as a whole. Page chose a combination of Pantone Matching System (PMS) colors magenta (pink), lavender (purple), and royal (blue).[17] The finished rectangular flag consists of a broad pink stripe at the top, a broad stripe in blue at the bottom, and a narrow purple stripe in the center.

Page described the meaning of the colors as, "The pink color represents sexual attraction to the same sex only (gay and lesbian), the blue represents sexual attraction to the opposite sex only (straight) and the resultant overlap color purple represents sexual attraction to both sexes (bi)."[17] He also described the flag's meaning in deeper terms, stating "The key to understanding the symbolism in the Bi Pride Flag is to know that the purple pixels of color blend unnoticeably into both the pink and blue, just as in the 'real world' where bi people blend unnoticeably into both the gay/lesbian and straight communities."[17][18]

Page stated that he took the colors and overlap for the flag from the biangles symbol of bisexuality.[19][20] The blue and pink overlapping triangle symbol is the biangles symbol of bisexuality, and was designed by artist Liz Nania as she co-organized a bisexual contingent for the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987.[20][21] The design of the biangles began with the pink triangle, a Nazi concentration camp badge that later became a symbol of gay liberation representing homosexuality. The addition of a blue triangle contrasts the pink and represents heterosexuality. The two triangles overlap and form lavender, which represents the "queerness of bisexuality", referencing the Lavender Menace and 1980s and 1990s associations of lavender with queerness.[22]

男同性戀

編輯Various pride flags have been used to symbolize gay men. Rainbow flags have been used since 1978 to represent both gay men and, subsequently, the LGBTQ community as a whole. Since the 2010s, various designs have been proposed to specifically represent the gay male community.

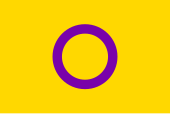

雙性人

編輯

The intersex flag was created by Morgan Carpenter of Intersex Human Rights Australia in July 2013 to create a flag "that is not derivative, but is yet firmly grounded in meaning". The organization describes the circle as "unbroken and unornamented, symbolising wholeness and completeness, and our potentialities. We are still fighting for bodily autonomy and genital integrity, and this symbolises the right to be who and how we want to be".[23][24][25]

女同性戀

編輯No single design for a lesbian-pride flag has been widely adopted.[26] However, many popular ones exist.

The labrys lesbian flag was created in 1999 by graphic designer Sean Campbell, and published in June 2000 in the Palm Springs edition of the Gay and Lesbian Times Pride issue.[26][27] The design involves a labrys, a type of double-headed axe, superimposed on the inverted black triangle, set against a violet background. Among its functions, the labrys was associated as a weapon used by the Amazons of mythology.[28][29] In the 1970s it was adopted as a symbol of empowerment by the lesbian feminist community.[30] Women considered asocial by Nazi Germany for not conforming to the Nazi ideal of a woman, which included homosexual females, were condemned to concentration camps[31] and wore an inverted black triangle badge to identify them.[32] Some lesbians reclaimed this symbol as gay men reclaimed the pink triangle (many lesbians also reclaimed the pink triangle although lesbians were not included in Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code).[32] The color violet became associated with lesbians via the poetry of Sappho.[33]

The lipstick lesbian flag was introduced by Natalie McCray in 2010 in the weblog This Lesbian Life.[34][35] The design contains a red kiss in the left corner, superimposed on seven stripes consisting of six shades of red and pink colors and a white bar in the center.[36][37] The lipstick lesbian flag represents "homosexual women who have a more feminine gender expression", but has not been widely adopted.[26] Some lesbians are against it because it does not include butch lesbians, while others have accused McCray of writing biphobic, racist, and transphobic comments on her blog.[38]

The "pink" lesbian flag was derived from the lipstick lesbian flag but with the kiss mark removed.[37] The pink flag attracted more use as a general lesbian pride flag.[39]

The "orange-pink" lesbian flag, modeled after the seven-band pink flag, was introduced on Tumblr by blogger Emily Gwen in 2018.[40][41] The colors include dark orange for "gender non-conformity", orange for "independence", light orange for "community", white for "unique relationships to womanhood", pink for "serenity and peace", dusty pink for "love and sex", and dark rose for "femininity".[41] A five-stripes version was soon derived from the 2018 colors.[42]

-

The lipstick lesbian flag was introduced in 2010 by Natalie McCray; this is a version with the kiss symbol changed.[35]

-

Pink lesbian flag with colors copied from the lipstick lesbian flag[39]

-

Orange-pink lesbian flag derived from the pink lesbian flag, circulated on social media in 2018[41]

-

Five-stripes variant of orange-pink flag[42]

非二元性別

編輯

The non-binary pride flag was created in 2014 by Kye Rowan.[44] Each stripe color represents different types of non-binary identities: yellow for people who identify outside of the gender binary, white for non-binary people with multiple genders, purple for those with a mixture of both male and female genders, and black for agender individuals.[45]

泛性戀

編輯

The pansexual pride flag was introduced in October 2010 in a Tumblr blog ("Pansexual Pride Flag").[46][47] It has three horizontal bars that are pink, yellow and blue.[46][48][49][來源可靠?] "The pink represents being attracted to women, the blue being attracted to men, and the yellow for being attracted to everyone else";[46] such as non-binary gender identities.[49][15][50][51]

跨性別

編輯

The transgender pride flag was designed by transgender woman Monica Helms in 1999.[52] It was first publicly displayed at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, US, in 2000.[53] It was flown from a large public flagpole in San Francisco's Castro District beginning November 19, 2012, in commemoration of the Transgender Day of Remembrance.[53] The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes: two light blue, two pink, with a white stripe in the center. Helms described the meaning of the flag as follows:[54]

The stripes at the top and bottom are light blue, the traditional color for baby boys. The stripes next to them are pink, the traditional color for baby girls.[53] The white stripe is for people that are nonbinary, feel that they don't have a gender.[55][56] The pattern is such that no matter which way you fly it, it is always correct, signifying us finding correctness in our lives.[53]

Philadelphia became the first county government in the United States to raise the transgender pride flag in 2015. It was raised at City Hall in honor of Philadelphia's 14th Annual Trans Health Conference, and remained next to the US and City of Philadelphia flags for the entirety of the conference. Then-Mayor Michael Nutter gave a speech in honor of the trans community's acceptance in Philadelphia.[57]

畫廊

編輯基於性取向的旗幟

編輯基於戀愛傾向的旗幟

編輯基於性別認同的旗幟

編輯其他旗幟

編輯基於區域的旗幟

編輯-

Serbia

Gay pride flag of Serbia[98]

參考資料

編輯- ^ Sobel, Ariel. The Complete Guide to Queer Pride Flags. The Advocate. June 13, 2018 [January 6, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於February 9, 2019).

- ^ Original 1978 rainbow flag designed by Gilbert Baker acquired by San Francisco's GLBT Historical Society. The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. June 17, 2021 [December 7, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於December 7, 2022).

- ^ Rainbow Flag: Origin Story. Gilbert Baker Foundation. 2018. (原始內容存檔於June 18, 2018).

- ^ Symbols of Pride of the LGBTQ Community. Carleton College. April 26, 2005 [January 23, 2012]. (原始內容存檔於February 10, 2012).

- ^ Rochman, Sue. Rainbow flap. The Advocate. June 20, 2000: 16 [August 21, 2018].

- ^ Riffenburg, Charles Edward IV. Symbols of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Movements. Queer Resources Directory. 2004 [July 25, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於July 22, 2019).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Parsons, Vic. Progress Pride flag gets 2021 redesign to better represent intersex people. PinkNews. June 7, 2021 [June 10, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-06-10).

- ^ Alao, Lola Christina; Lawrence, India. The trans and intersex-inclusive Pride flags will fly on Regent Street again soon. Time Out. June 12, 2023 [2024-10-31]. (原始內容存檔於2025-01-02).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Gillespie, Claire. 22 Different Pride Flags and What They Represent in the LGBTQ+ Community. Health.com. [July 19, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於July 19, 2020).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Queer Community Flags. [March 11, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 4, 2023).

- ^ Bilić, Bojan; Kajinić, Sanja. Intersectionality and LGBT Activist Politics: Multiple Others in Croatia and Serbia. Springer. 2016: 95–96.

- ^ Decker, Julie. The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality. Skyhorse.

- ^ The Asexuality Flag. Asexuality Archive. February 20, 2012 [September 26, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於September 17, 2021).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 The Ace and Aro Advocacy Project. Ace and Aro Journeys. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2023: 44–45.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Petronzio, Matt. A Storied Glossary of Iconic LGBT Flags and Symbols (Gallery). Mashable. June 13, 2014 [July 17, 2014]. (原始內容存檔於April 3, 2019).

- ^ Sobel, Ariel. The Complete Guide to Queer Pride Flags. The Advocate. June 13, 2018 [June 28, 2018]. (原始內容存檔於June 28, 2018).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Page, Michael. History of the Bi Pride Flag. BiFlag.com. 2001 [January 23, 2012]. (原始內容存檔於August 1, 2001).

- ^ What Exactly Is The Bisexual Pride Flag, And What Does It Mean?. November 9, 2021 [December 7, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於December 7, 2022) (英語).

- ^ History, Bi Activism, Free Graphics. BiFlag.com. 1998-12-05 [2020-04-20]. (原始內容存檔於2001-08-01).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Biangles, bisexual symbol, bi colors, bi history. Liz Nania. [2024-10-31]. (原始內容存檔於2024-04-26).

- ^ Jordahn, Sebastian. Queer x Design highlights 50 years of LGBT+ graphic design. Dezeen. 2019-10-23 [2021-06-12]. (原始內容存檔於2021-06-13).

- ^ Biangles, bisexual symbol, bi colors, bi history — Liz Nania. Liz Nania. [2022-06-26]. (原始內容存檔於2024-04-26) (美國英語).

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan. An intersex flag. Intersex Human Rights Australia. July 5, 2013 [February 17, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於July 9, 2018).

- ^ Yu, Ming. Are you male, female or intersex?. Amnesty International. July 11, 2013 [February 17, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於September 23, 2016).

- ^ Busby, Cec. Intersex advocates address findings of Senate Committee into involuntary sterilisation. Gay News Network. October 28, 2013 [January 15, 2016]. (原始內容存檔於January 15, 2016).

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Bendix, Trish. Why don't lesbians have a pride flag of our own?. AfterEllen. September 8, 2015 [June 8, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於September 9, 2015).

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Brabaw, Kasandra. A Complete Guide To All The LGBTQ+ Flags & What They Mean. Refinery29. June 19, 2019 [July 6, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於March 12, 2021).

- ^ Gay Symbols Through the Ages. The Alyson Almanac: A Treasury of Information for the Gay and Lesbian Community. Boston, Massachusetts: Alyson Publications. 1989: 99–100. ISBN 0-932870-19-8.

- ^ Murphy, Timothy F. (編). Reader's Guide to Lesbian and Gay Studies 1st. Chicago, Illinois: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. 2000: 44. ISBN 1-57958-142-0.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 Zimmerman, Bonnie (編). Symbols (by Christy Stevens). Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia . 1 (Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures) 1st. Garland Publishing. 2000: 748. ISBN 0-8153-1920-7.

- ^ Lesbians Under the Nazi Regime. Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. March 31, 2021 [January 28, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於March 25, 2022).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Elman, R. Amy. Triangles and Tribulations: The Politics of Nazi Symbols. Remember.org. [December 10, 2016]. (原始內容存檔於December 20, 2016). (Originally published as Elman, R. Amy. Triangles and Tribulations: The Politics of Nazi Symbols. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996, 30 (3): 1–11. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 8743114. doi:10.1300/J082v30n03_01.)

- ^ Prager, Sarah. Four Flowering Plants That Have Been Decidedly Queered (Sapphic Violets). JSTOR Daily. January 29, 2020 [July 19, 2020]. (原始內容存檔於February 3, 2021).

- ^ Mathers, Charlie. 18 Pride flags you might not have seen before. Gay Star News. January 1, 2018 [June 4, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於June 1, 2021). (The Mathers article shows the derivative design, but not the original flag.)

- ^ 35.0 35.1 Redwood, Soleil. A Horniman Lesbian Flag. Horniman Museum. February 26, 2020 [November 21, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於August 16, 2023).

- ^ McCray, Natalie. LLFlag. This Lesbian Life. July 2010 [June 9, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於October 11, 2016).

- ^ 37.0 37.1 Rawles, Timothy. The many flags of the LGBT community. San Diego Gay & Lesbian News. July 12, 2019 [September 3, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於July 12, 2019).

- ^ Brabaw, Kasandra. A Complete Guide To All The LGBTQ+ Flags & What They Mean. Refinery29. [January 28, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於January 28, 2023).

- ^ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Andersson, Jasmine. Pride flag guide: what the different flags look like, and what they all mean. i. July 4, 2019 [September 15, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於August 24, 2019).

- ^ Dastagir, Alia E.; Oliver, David. LGBTQ Pride flags go beyond the classic rainbow. Here's what each one means. USA Today. June 1, 2021 [June 11, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於June 1, 2021).

- ^ 41.0 41.1 41.2 LGBTQIA+ Symbols: Lesbian Flags. Old Dominion University. April 2020 [June 6, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於June 2, 2021).

- ^ 42.0 42.1 Murphy-Kasp, Paul. Pride in London: What do all the flags mean?. BBC News. July 6, 2019 [July 6, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於June 17, 2020). (video)

- ^ Variations of the Gay Pride Rainbow Flag: Rainbow flags with double Venus symbol. Flags of the World. September 5, 2020 [June 3, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於February 27, 2021).

- ^ Glass, Jess. Pride flags: All of the flags you might see at Pride and what they mean. PinkNews. June 26, 2018 [April 19, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於April 19, 2019).

- ^ Everything you never understood about being nonbinary. Gaygull. [April 19, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於October 31, 2020).

- ^ 46.0 46.1 46.2 A field guide to Pride flags. Clare Bayley. June 27, 2013 [July 17, 2014]. (原始內容存檔於July 24, 2014).

- ^ What Is The Pansexual Pride Flag, And What Does It Stand For?. November 10, 2021 [December 7, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於December 7, 2022) (英語).

- ^ Pansexual Pride Day Today. Shenandoah University. December 5, 2016 [July 17, 2014]. (原始內容存檔於August 20, 2017).

- ^ 49.0 49.1 Do You Have a Flag?. Freedom Requires Wings. November 9, 2012 [July 17, 2014]. (原始內容存檔於February 27, 2013).

- ^ Cantú Queer Center - Sexuality Resources. [July 17, 2014]. (原始內容存檔於May 17, 2017).

- ^ Gay & Lesbian Pride Symbols - Common Pride Symbols and Their Meanings. [July 17, 2014]. (原始內容存檔於September 28, 2016).

- ^ Fairyington, Stephanie. The Smithsonian's Queer Collection. The Advocate. November 12, 2014 [June 5, 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2021-04-23).

- ^ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 LOOK: Historic Transgender Flag Flies Over The Castro. HuffPost. November 20, 2012 [December 7, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於October 23, 2022) (英語).

- ^ What Is The Transgender Pride Flag, And What Does It Stand For?. November 10, 2021 [December 7, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於December 7, 2022) (英語).

- ^ Gray, Emma; Vagianos, Alanna. We Have A Navy Veteran To Thank For The Transgender Pride Flag. Huffington Post. July 27, 2017 [August 31, 2017]. (原始內容存檔於September 1, 2018).

- ^ LB, Branson. The Veteran Who Created The Trans Pride Flag Reacts To Trump's Trans Military Ban. Buzzfeed. July 26, 2017 [August 31, 2018]. (原始內容存檔於September 1, 2018).

- ^ Philadelphia Raises the Transgender Pride Flag for the First Time. The Advocate. June 4, 2015 [September 26, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於February 20, 2019).

- ^ 58.00 58.01 58.02 58.03 58.04 58.05 58.06 58.07 58.08 58.09 58.10 Barron, Victoria. Perfectly Queer: An Illustrated Introduction. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2023.

- ^ A Comprehensive Guide to Pride Flags and their Meanings. San Francisco Gay Men's Chorus. April 17, 2023 [April 22, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 22, 2023).

- ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Wilson, Amee. Queer Chameleon and Friends. Penguin Random House Australia. 2023.

- ^ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Yuko, Elizabeth. The Meaning Behind 32 LGBTQ Pride Flags. Reader's Digest. March 13, 2023 [April 22, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 17, 2023).

- ^ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 62.5 62.6 62.7 62.8 Campbell, Andy. Queer X Design: 50 Years of Signs, Symbols, Banners, Logos, and Graphic Art of LGBTQ. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. 2019: 218-221. ISBN 9780762467853.

- ^ All about the demisexual flag. LGBTQ Nation. June 30, 2022 [January 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於January 8, 2023).

- ^ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Davis, Chloe O. The Queens' English: The LGBTQIA+ Dictionary of Lingo and Colloquial Phrases. Clarkson Potter. 2021: 86-87.

- ^ LGBTQ+ Pride Flags and What They Stand For. Volvo Group. 2021 [August 17, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於August 17, 2021).

- ^ Pride Flags. Rainbow Directory. [September 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於September 27, 2021).

- ^ PRIDE FLAGS. Queer Lexicon. 22 July 2017 [16 August 2023]. (原始內容存檔於15 July 2023). 已忽略未知參數

|lang=(建議使用|language=) (幫助) - ^ Campano, Leah. What Does It Mean to Be Graysexual?. Seventeen. October 4, 2022 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於August 16, 2023).

- ^ Redwood, Soleil. A Horniman Lesbian Flag. Horniman Museum. February 26, 2020 [September 20, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於August 16, 2023).

- ^ 70.0 70.1 LGBTQIA+ Flags and Symbols. Old Dominion University. [September 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於June 19, 2021).

- ^ Murphy-Kasp, Paul. Pride in London: What do all the flags mean?. BBC News (BBC). July 6, 2019. 00:20 [July 6, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於June 17, 2020).

- ^ LGBTQ+ Pride Flags. Human Rights Campaign. [2024-06-06]. (原始內容存檔於2025-01-01) (美國英語).

- ^ Omnisexual Meaning | Understand This Sexual Orientation. Dictionary.com. August 7, 2018 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 13, 2023).

- ^ Washington-Harmon, Taylyn. What Does It Mean To Be Omnisexual?. Health.com. November 25, 2022 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 23, 2023).

- ^ Queer Community Flags. Queer Events. September 14, 2018 [June 4, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於April 4, 2023).

- ^ Pride Flags Glossary | Resource Center for Sexual & Gender Diversity. rcsgd.sa.ucsb.edu. [2024-08-01]. (原始內容存檔於2024-12-04).

- ^ Let's Discuss What It Means to Be Greyromantic. Cosmopolitan. 2022-07-26 [2024-08-01]. (原始內容存檔於2024-12-13) (美國英語).

- ^ Polyamory: What Is It and Why Does the Flag Have the Pi Symbol on It?. Rare. May 4, 2021 [September 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於September 27, 2021).

- ^ Burkett, Eric. LGBTQ Agenda: New polyamorous flag is revealed. The Bay Area Reporter. December 20, 2022 [April 22, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 6, 2023).

- ^ New Tricolor Polyamory Pride Flag. November 23, 2022 [November 27, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於November 23, 2022).

- ^ * Bigender Flag – What Does It Represent?. Symbol Sage. August 26, 2020 [May 28, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於June 1, 2021).

- bigender Meaning | Gender & Sexuality. Dictionary.com. 27 February 2019 [November 25, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於November 25, 2022) (美國英語).

- Bigender Pride Flag. Sexual Diversity. November 22, 2022 [November 25, 2022]. (原始內容存檔於November 25, 2022) (美國英語).[來源可靠?]

- ^ ralatalo. Flags of the LGBTIQ Community. OutRight Action International. September 20, 2021 [September 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於October 10, 2021).

- ^ 83.0 83.1 Pride Flags. The Gender and Sexuality Resource Center. [2024-08-01]. (原始內容存檔於2018-05-28) (英語).

- ^ 84.0 84.1 LGBTQ+ Pride Flags and What They Stand For. www.volvogroup.com. 2022-11-06 [2024-08-01]. (原始內容存檔於2021-08-17) (英語).

- ^ 31 Queer Pride Flags to Know. The Advocate. [January 7, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於January 8, 2023).

- ^ pangender Meaning | Gender & Sexuality. Dictionary.com. July 1, 2019 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 19, 2023).

- ^ Transmasculine Flag Color Codes. flagcolorcodes.com. [May 18, 2024]. (原始內容存檔於April 7, 2024).

- ^ Pride Flags. University of Northern Colorado: The Gender and Sexuality Resource Center. [April 22, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於May 28, 2018).

- ^ Canadian gay rainbow flag at Montreal gay pride parade 2017. Country Rogers Digital Media: 107.3 (CJDL FM). Published August 20, 2017. 31 May 2023 [November 29, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2024-12-07).

- ^ Saskatoon's gay pride parade on June 16, 2012. Daryl Mitchell. Published June 30, 2012. 15 June 2012 [November 29, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2024-12-07).

- ^ Canada Pride Flag. Default Store View. [November 29, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於November 29, 2021).

- ^ Chicago gay pride parade expels Star of David flags. BBC News. June 26, 2017 [September 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於September 27, 2021).

- ^ Sales, Ben. The controversy over the DC Dyke March, Jewish Pride flags and Israel, explained. Times of Israel. [September 27, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於September 27, 2021).

- ^ Owens, Ernest. Philly's Pride Flag to Get Two New Stripes: Black and Brown. Philadelphia. June 8, 2017 [May 26, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於May 24, 2019).

- ^ Deane, Ben. The Philly Pride flag, explained. The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 2021 [April 23, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於April 23, 2023).

- ^ Pride parades in Poland prove flashpoint ahead of general election. Reuters. [July 4, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於July 4, 2023).

- ^ Polish LGBT people could be prosecuted for 'desecrating a national symbol'. Pink News. July 9, 2018 [July 4, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於July 4, 2023).

- ^ Pride Parade, Trans Pride take place in Belgrade. European Western Balkans. 2015-09-20 [2023-08-04]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-27).

- ^ Government Notice 377. Government Gazette. 11 May 2012, (35313). (原始內容存檔於25 July 2014).

- ^ Grange, Helen. Coming out is risky business. Independent Online. January 31, 2011 [July 4, 2019]. (原始內容存檔於March 22, 2021).

- ^ South African Flag Revealed at MCQP. Cape Town Pride. 22 December 2010 [4 April 2011]. (原始內容存檔於9 August 2011).

- ^ Knowles, Katherine. God save the queers. PinkNews. July 21, 2006 [May 17, 2021]. (原始內容存檔於October 14, 2006).

- ^ Pink Union Jack. The Flag Shop. [November 29, 2023]. (原始內容存檔於2024-03-22).

| 這是一篇與旗幟相關的小作品。您可以透過編輯或修訂擴充其內容。 |

![Labrys lesbian flag created in 1999 by Sean Campbell[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Labrys_Lesbian_Flag.svg/100px-Labrys_Lesbian_Flag.svg.png)

![The lipstick lesbian(英語:lipstick lesbian) flag was introduced in 2010 by Natalie McCray; this is a version with the kiss symbol changed.[35]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/Lipstick_lesbian_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Lipstick_lesbian_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Pink lesbian flag with colors copied from the lipstick lesbian flag[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Lesbian_Pride_pink_flag.svg/100px-Lesbian_Pride_pink_flag.svg.png)

![Orange-pink lesbian flag derived from the pink lesbian flag, circulated on social media in 2018[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Lesbian_pride_flag_2018.svg/90px-Lesbian_pride_flag_2018.svg.png)

![Five-stripes variant of orange-pink flag[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Lesbian_Pride_Flag_2019.svg/107px-Lesbian_Pride_Flag_2019.svg.png)

![Variant of the rainbow pride flag with the double-Venus symbol[43][30]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/Lesbian_Pride_double-Venus_canton_rainbow_flag.svg/100px-Lesbian_Pride_double-Venus_canton_rainbow_flag.svg.png)

![Abrosexual[58][59][60][61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/Abrosexual_flag.svg/100px-Abrosexual_flag.svg.png)

![Asexual[62][14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Asexual_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Asexual_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Bisexual[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/Bisexual_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Bisexual_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Demisexual[63][64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/Demisexual_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Demisexual_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Gay men[65][66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Gay_Men_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Gay_Men_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Gay men (five stripes)[67]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/5-striped_New_Gay_Male_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-5-striped_New_Gay_Male_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Gray asexual/graysexual[68][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Grey_asexuality_flag.svg/100px-Grey_asexuality_flag.svg.png)

![Omnisexual[58][60][73][74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Omnisexuality_flag.svg/100px-Omnisexuality_flag.svg.png)

![Polysexual[70][62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ae/Polysexuality_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Polysexuality_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Aromantic[75][14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Aromantic_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Aromantic_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Demiromantic[61][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/Demiromantic_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Demiromantic_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Grayromantic[76][77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Gray-aromantic_Pride_Flag.png/107px-Gray-aromantic_Pride_Flag.png)

![Polyamory (design created in 1995 by Jim Evans)[78][61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Polyamory_Pride_Flag.svg/90px-Polyamory_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Polyamory (design created in 2022 by Red Howell)[79][80]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Tricolor_Polyamory_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Tricolor_Polyamory_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Agender[27][62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/Agender_pride_flag.svg/86px-Agender_pride_flag.svg.png)

![Bigender[81]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Bigender_Flag.svg/100px-Bigender_Flag.svg.png)

![Demiboy[64][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Demiboy_Flag.svg/86px-Demiboy_Flag.svg.png)

![Demigirl[64][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Demigirl_Flag.svg/86px-Demigirl_Flag.svg.png)

![Genderfluid[82][62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Genderfluidity_Pride-Flag.svg/100px-Genderfluidity_Pride-Flag.svg.png)

![Genderflux[83][84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Genderflux_Pride_Flag.png/100px-Genderflux_Pride_Flag.png)

![Genderqueer[85][62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Genderqueer_Pride_Flag.svg/100px-Genderqueer_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Maverique[83][84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3d/Maverique_flag.svg/100px-Maverique_flag.svg.png)

![Pangender[86][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Pangender_flag.svg/100px-Pangender_flag.svg.png)

![Transmasc[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Transmasc_Flag.svg/100px-Transmasc_Flag.svg.png)

![Aroace[58][60] (Aromantic-Asexual)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Aroace_flag.svg/100px-Aroace_flag.svg.png)

![Bear[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/Bear_Brotherhood_flag.svg/100px-Bear_Brotherhood_flag.svg.png)

![Intersex[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Intersex_Pride_Flag.svg/90px-Intersex_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Leather[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7e/Leather%2C_Latex%2C_and_BDSM_pride_-_Light.svg/90px-Leather%2C_Latex%2C_and_BDSM_pride_-_Light.svg.png)

![Queer[58][60]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Queer_Flag.svg/100px-Queer_Flag.svg.png)

![Two-spirit[88][58][60][61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Two-Spirit_Flag.svg/100px-Two-Spirit_Flag.svg.png)

![Canada Canadian pride Flag[89][90][91]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Canada_Pride_flag.svg/90px-Canada_Pride_flag.svg.png)

![Israel Gay Jewish Pride Flag[92][93]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/05/Gay_Pride_flag_of_Israel.svg/83px-Gay_Pride_flag_of_Israel.svg.png)

![Philadelphia, United States People of color pride flag[94][58][95]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/Philadelphia_Pride_Flag.svg/98px-Philadelphia_Pride_Flag.svg.png)

![Poland Gay pride flag of Poland[96][97]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Gay_Pride_Flag_of_Poland.svg/96px-Gay_Pride_Flag_of_Poland.svg.png)

![Serbia Gay pride flag of Serbia[98]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Pride_flag_Serbia_basic.png/90px-Pride_flag_Serbia_basic.png)

![South Africa Gay pride flag of South Africa[99][100][101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Gay_Flag_of_South_Africa.svg/90px-Gay_Flag_of_South_Africa.svg.png)

![United Kingdom Pink Union Jack[102][103]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/15/Gay_Pride_flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg/120px-Gay_Pride_flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg.png)