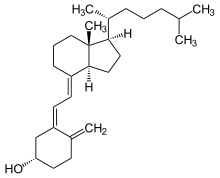

胆钙化醇

此条目需要扩充。 (2011年9月14日) |

胆钙化醇(英语:cholecalciferol) ,也称为维生素D3,或是拼写为colecalciferol,是维生素D中的一种,由皮肤暴露于紫外线时产生,它也存在于某些食物中,可作为营养补充品。[3]

| |

| |

| 临床资料 | |

|---|---|

| 读音 | /ˌkoʊləkælˈsɪfərɒl/ |

| 其他名称 | vitamin D3 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 专业药物信息 |

| 核准状况 | |

| 给药途径 | 口服给药, 肌肉注射 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 67-97-0 |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.612 |

| 化学信息 | |

| 化学式 | C27H44O |

| 摩尔质量 | 384.65 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| 熔点 | 83至86 °C(181至187 °F) |

| 沸点 | 496.4 °C(925.5 °F) |

| 水溶性 | 几乎不溶于水,易溶于乙醇、甲醇和其他一些有机溶剂。微溶于植物油。 |

| |

| |

人体皮肤于接受阳光照射后就会生成胆钙化醇,[4]然后在肝脏中转化为骨化二醇(25-羟基胆骨化醇 D),在肾脏中进一步转化为骨化三醇(1,25-二羟基胆骨化醇 D)。[4]骨化三醇最重要的功能之一是促进肠道吸收钙。[5]胆钙化醇存在于多脂鱼类、牛肝、鸡蛋和起司等食物中。[6][7]在一些国家,也会把胆钙化醇添加到植物性食品、牛奶、果汁、优格和人造奶油等产品之中。[6][7]

胆钙化醇可作为口服营养补充剂,以预防维生素D缺乏症,或作为治疗相关疾病(如佝偻病)的药物。[8][9]它也用于治疗性联遗传型低磷酸盐佝偻症、导致低血钙症的副甲状腺功能低下症和范康尼氏症候群。[9][10]维生素D补充剂可能对罹患严重肾脏病变的人无效。[11][10]摄取胆钙化醇过量会导致呕吐、便秘、肌肉无力和精神错乱,其他的风险有肾结石。[5]通常每天摄取超过40,000国际单位(1,000微克)的剂量就会导致高血钙发生。[12]对于健康的孕妇而言,每天摄取800到2,000国际单位的剂量属于安全,不会对母体或胎儿造成危害。[5]

科学家于1936发现这种营养素,将其命名为"胆钙化醇"。[13]它已被列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中。[14]它在美国于2022年最常使用处方药中排名第62,开立的处方笺数量超过1,000万张。[15][16]市面上有其通用名药物流通。[10][17][18]

医疗用途

编辑胆钙化醇(维生素D3)似乎可刺激人体I型干扰素讯号系统,以保护人体免受细菌和病毒的侵害,此点与维生素D2(麦角钙化醇)不同。

维生素D缺乏症

编辑胆钙化醇是维生素D中的一种,在皮肤中自然合成,可发挥激素原作用,之后转化为骨化三醇。此过程对于维持身体钙水平和促进骨骼健康和发育非常重要。胆钙化醇作为药物用途时,可作为营养补充剂,以预防或治疗维生素D缺乏症。一克胆钙化醇的含量有40,000,000 (40×106) 国际单位,1国际单位等于0.025微克。膳食参考摄取量(Dietary Reference Intake, DRI)之维生素D(麦角钙化醇(D2),或胆钙化醇(D3),或两者)皆已建立,建议摄取量因国家而异:

- 美国:15微克/天(600国际单位/天),适用于1岁至70岁(含)的所有个体(男性、女性、孕妇/哺乳期妇女)。对于所有70岁以上的个体,建议摄取量为20微克/天(800国际单位/天)。[19]

- 欧盟:假设在皮肤维生素D合成最少的情况下,所有1岁以上的个体15微克/天(600国际单位/天),7-11个月的婴儿10微克/天(400微克/天)。[20]

- 英国:1岁以下婴儿(包括纯母乳哺育的婴儿)的"安全摄取量"(Safety Intake,SI) 为8.5–10微克/天(340–400国际单位/天),1岁到不足4岁儿童的SI为10微克/天(400国际单位/天)。对于所有4岁及以上族群(包括孕妇/哺乳期妇女),参考营养素摄取量 (RNI) 为10微克/天(400国际单位/天)。[21]

维生素D3水平低下的情况更常见于生活在北纬地区(通常指北回归线以北的中高纬度地区)或因其他原因缺乏定期照射阳光的人,包括足不出户、体弱、年老或肥胖、肤色较深以及穿着遮盖大部分身体的衣服。[22][23]建议这些族群补充维生素D3。[23]

美国国家医学院在2010年建议维生素D的最大摄取量为4,000国际单位/天。相较于建议的每日4,000国际单位,高达10倍的剂量(40,000国际单位)经长期摄取后,才可能产生副作用。[24]患有严重维生素D缺乏症的患者需要接受负荷剂量治疗,剂量可根据实际血清25-羟基维生素D水平和体重计算。[25]

关于胆钙化醇与麦角钙化醇的相对有效性,存在互有矛盾的报导,一些研究显示前者的功效较差,而其他研究则显示两者没差异。两者的吸收、结合和失活存在差异,虽然证据通常支持胆钙化醇可提高血液中维生素D的水平,仍需要进行更多的研究以将此厘清。[26]

使用胆钙化醇治疗佝偻病的一种较不常见的方式是使用单次大剂量,称为stoss疗法(stoss为德语,与英文的shcok同义)。[27][28][29]治疗方式为一次口服或肌肉注射300,000国际单位(7,500微克)至500,000国际单位(12,500微克, 等于12.5毫克),有时则分2至4剂给药。但人们会担心使用如此大剂量是否有安全性的问题。[29]

男性循环系统中维生素D水平较低与总睾酮水平较低有关联。补充维生素D可能提高总睾固酮浓度,但仍需进行更多研究。[30]

其他疾病

编辑于2007年所进行的一项统合分析,结论是每天摄取1,000至2,000国际单位的维生素D3可在最小的风险下降低大肠癌发生率。[31]此外,于2008年发表在美国同行评审医学期刊《癌症研究》上的一项研究报告,显示在一些小鼠的饮食(这些小鼠的营养成分与新的西方饮食相似)中添加1,000国际单位胆钙化醇(连同钙),可预防结肠肿瘤发生。[32]在一项包括有36,282名妇女,为期平均7年的实验中,有18,176名每天补充400国际单位(分两次服用,每次200国际单位)胆钙化醇补充剂(附加钙),其余的服用等量的安慰剂,结果为两个群组中的大肠癌发生风险并无显著的差异。[33]

因为胆钙化醇作用非常小,不建议将其用来预防癌症。[34]虽然人体的血清胆钙化醇水平低与各种癌症、多发性硬化症、结核病、心脏病和糖尿病高发生率之间存在相关性,[35]但科学界的共识是为此过量补充胆钙化醇水平并无益处。[36]人们认为结核病可能会导致人体胆钙化醇水平降低。[37]然而两者之间的关系尚未被完全了解。[38]

生物化学

编辑结构

编辑胆钙化醇是维生素D的五种形式之一。[39]它是一种类固醇,即一种开环的类固醇分子。[40]

作用机转

编辑胆钙化醇本身没活性。它透过两次羟基化而转为活性形式:第一次在肝脏中透过细胞色素P450CYP2R1或CYP27A1羟基化,形成25-羟基胆钙化醇(骨化二醇、25-OH维生素 D3)。第二次羟基化主要发生在肾脏,透过激素CYP27B1的作用将25-OH维生素D3转化为 1,25-二羟基胆钙化醇(骨化三醇,1,25-(OH)2 维生素D3)。这些代谢物在血液中与维生素D结合蛋白结合。骨化三醇的作用由维生素D受体介导,维生素D受体是一种核受体,可调节数百种蛋白质的合成,几乎于体内的每个细胞中都有此核受体存在。[4]

生物合成

编辑点击右下角图示即可打开。

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: VitaminDSynthesis_WP1531.

7-脱氢胆固醇是胆钙化醇的前驱物。在皮肤表皮层内,7-脱氢胆固醇由波长在290至310奈米(nm)之间的紫外线光发生电循环反应,合成峰值在波长293奈米时发生。

虽然阳光中几乎不存在活性紫外线波长,但根据阳光的强度,皮肤适度暴露即可产生足够数量的胆钙化醇。一天中的时间、季节、纬度和海拔会影响阳光的强度,[41]而污染、云或玻璃都会减少紫外线暴露量。将脸部、手臂和腿部的皮肤平均每周曝露两次,每次5-30分钟可能就足够。但皮肤越黑,阳光越弱,所需暴露时间就越长。紫外线照射不会导致维生素D合成过量,皮肤会自动调节维生素D的生成与消耗,使其维持在一个相对稳定的水平。[41]

利用室内晒黑的紫外线灯光也可让皮肤产生胆钙化醇,这些紫外线灯主要产生UVA光谱中(波长为315-400奈米)的紫外线。经常使用室内晒黑服务者血液中的胆钙化醇含量较高。[41]

研究发现波长293奈米UVB发光二极管 (LED) 在不到1⁄60的时间内产生维生素D3的效率是太阳的2.4倍。(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28904394/ (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)).

根据定义,胆钙化醇和所有形式的维生素D是否都是"维生素"仍有争议,因为在维生素的定义中,该物质不能由人体合成,而必须依靠摄取。但胆钙化醇是人体在UVB辐射暴露期间所合成。[4]

工业生产

编辑胆钙化醇经由大量生产,用作维生素补充剂和将食品营养强化之用。作为药物,它被称为cholecalciferol (美国采用名称(USAN)) 或是colecalciferol (国际非专有药名(INN)、英国核准名称(BAN))。制作方式为从羊毛中的绵羊油中提取的7-脱氢胆固醇,经紫外线照射而产生。绵羊油是从剪下的羊毛经清洁过程而得。油中的胆固醇经过四步骤生成7-脱氢胆固醇,与动物皮肤中产生的方式相同。[42]

稳定性

编辑胆钙化醇对紫外线辐射非常敏感,会迅速但可逆地分解形成超固醇,后者可进一步不可逆地转化为麦角固醇。[42]

灭鼠剂

编辑啮齿动物对高剂量胆钙化醇比其他物种更为敏感,因此被用作毒饵来控制这些有害动物。[45][18]

高剂量胆钙化醇灭鼠剂的机制是它会造成"高血钙 ,将全身软组织钙化,导致肾衰竭、心脏异常、高血压、中枢神经系统抑制和消化道不适。通常在摄入后18-36小时内就会出现症状 - 包括如忧郁、食欲不振、多尿和口渴。" [17]高剂量胆钙化醇通常会在脂肪组织中迅速积聚,而缓慢释放,[46]吃下毒饵动物的死亡时间往往会因此延迟数天。[45]

负鼠已成新西兰一种重要的有害动物。该国为达控制目的,采胆钙化醇作为诱杀的活性成分。[47]负鼠的半数致死量(LD50 )为16.8毫克/公斤,但在饵料中添加碳酸钙后,[48][49]可将LD50降到9.8毫克/公斤,攻击的目标为负鼠的肾脏及心脏。[50]据报导,兔子的LD50 为4.4毫克/公斤,几乎所有摄取剂量大于15毫克/公斤的兔子都会死亡。[51]据报导,多种胆钙化醇剂量均有毒性,狗的LD50,高的可达88毫克/公斤,最低致死量(LDLo)则为2毫克/公斤。[52]

研究人员提出此种化合物对非目标物种的毒性比前几代抗凝血灭鼠剂(华法林和同类物)或溴杀灵要低,[53]且尚未有继发性中毒(通过食用中毒动物而中毒)的记录出现。[17]然而同一报告称,其他动物(例如狗和猫)误食此类灭鼠剂诱饵或其他形式的胆钙化醇时,仍有对其构成重大危险的可能。[17]

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021. Health Canada. 2022-08-03 [2024-03-25]. (原始内容存档于2024-03-25).

- ^ Regulatory Decision Summary for Vitamin D3 Oral Solution. Health Canada. 2021-02-05 [2024-03-25].

- ^ Coulston AM, Boushey C, Ferruzzi M. Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Academic Press. 2013: 818 [2016-12-29]. ISBN 9780123918840. (原始内容存档于2016-12-30).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Norman AW. From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. August 2008, 88 (2): 491S–499S. PMID 18689389. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.2.491S .

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Cholecalciferol (Professional Patient Advice) - Drugs.com. www.drugs.com. [2016-12-29]. (原始内容存档于2016-12-30).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D. ods.od.nih.gov. 11 February 2016 [30 December 2016]. (原始内容存档于31 December 2016).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D (PDF). National Academies Press. 2011 [2024-11-07]. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828. S2CID 58721779. doi:10.17226/13050. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-04-20). 已忽略未知参数

|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 69. British Medical Association. 2015: 703–704. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 World Health Organization. Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR , 编. WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. 2009. ISBN 9789241547659. hdl:10665/44053.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hamilton R. Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2015: 231. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ Aviticol 1 000 IU Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC). www.medicines.org.uk. [2016-12-29]. (原始内容存档于2016-12-30).

- ^ Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. May 1999, 69 (5): 842–56 [2024-11-07]. PMID 10232622. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842 . (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-07-03).

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR. Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006: 451 [2016-12-29]. ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5. (原始内容存档于2016-12-30) (英语).

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771 . WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ The Top 300 of 2022. ClinCalc. [2024-08-30]. (原始内容存档于2024-08-30).

- ^ Cholecalciferol Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022. ClinCalc. [2024-08-30].

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Khan SA, Schell MM. Merck Veterinary Manual - Rodenticide Poisoning: Introduction. November 2014 [10 October 2021]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-15).

Incidence of vitamin D3 toxicosis in animals is relatively less than that of anticoagulant and bromethalin toxicosis. Relay toxicosis from vitamin D3 has not been documented.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Rizor SE, Arjo WM, Bulkin S, Nolte DL. Efficacy of Cholecalciferol Baits for Pocket Gopher Control and Possible Effects on Non-Target Rodents in Pacific Northwest Forests. Vertebrate Pest Conference (2006). USDA. [2019-08-27]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-14).

0.15% cholecalciferol bait appears to have application for pocket gopher control.' Cholecalciferol can be a single high-dose toxicant or a cumulative multiple low-dose toxicant.

- ^ DRIs for Calcium and Vitamin D 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2010-12-24.

- ^ Dietary reference values for vitamin D | EFSA. 2016-10-28.

- ^ Joint explanatory note by the European Food Safety Authority and the UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition regarding dietary reference values for vitamin D (PDF).

- ^ Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, Burckhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B, Eisman JA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Josse RG, Lips P, Morales-Torres J. Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int. November 2009, 20 (11): 1807–20 [2024-11-07]. PMID 19543765. S2CID 52858668. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-0954-6. (原始内容存档于2021-10-10).

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Vitamins and minerals – Vitamin D. National Health Service. 3 August 2020 [2020-11-15]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-30).

- ^ Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. May 1999, 69 (5): 842–56. PMID 10232622. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842 .

- ^ van Groningen L, Opdenoordt S, van Sorge A, Telting D, Giesen A, de Boer H. Cholecalciferol loading dose guideline for vitamin D-deficient adults. European Journal of Endocrinology. April 2010, 162 (4): 805–11. PMID 20139241. doi:10.1530/EJE-09-0932 .

- ^ Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S, et al. Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. June 2012, 95 (6): 1357–64. PMC 3349454 . PMID 22552031. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.031070.

- ^ Shah BR, Finberg L. Single-day therapy for nutritional vitamin D-deficiency rickets: a preferred method. The Journal of Pediatrics. September 1994, 125 (3): 487–90. PMID 8071764. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)83303-7.

- ^ Chatterjee D, Swamy MK, Gupta V, Sharma V, Sharma A, Chatterjee K. Safety and Efficacy of Stosstherapy in Nutritional Rickets. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology. March 2017, 9 (1): 63–69. PMC 5363167 . PMID 27550890. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.3557.

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Bothra M, Gupta N, Jain V. Effect of intramuscular cholecalciferol megadose in children with nutritional rickets. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. June 2016, 29 (6): 687–92. PMID 26913455. S2CID 40611968. doi:10.1515/jpem-2015-0031.

- ^ Chen C, Zhai H, Cheng J, Weng P, Chen Y, Li Q, et al. Causal Link Between Vitamin D and Total Testosterone in Men: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. August 2019, 104 (8): 3148–3156. PMID 30896763. S2CID 84841517. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01874 .

- ^ Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, Grant WB, Mohr SB, Lipkin M, et al. Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention: a quantitative meta analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine (Meta-Analysis). March 2007, 32 (3): 210–6. PMID 17296473. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004.

- ^ Yang K, Kurihara N, Fan K, Newmark H, Rigas B, Bancroft L, et al. Dietary induction of colonic tumors in a mouse model of sporadic colon cancer. Cancer Research. October 2008, 68 (19): 7803–10. PMID 18829535. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1209 .

- ^ Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Brunner RL, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. February 2006, 354 (7): 684–96 [2024-11-07]. PMID 16481636. S2CID 20826870. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055222 . (原始内容存档于2021-08-28).

- ^ Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Whitfield K, Wetterslev J, Simonetti RG, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. January 2014, 1 (1): CD007470. PMC 11285307 . PMID 24414552. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007470.pub3.

- ^ Garland CF, Garland FC, Gorham ED, Lipkin M, Newmark H, Mohr SB, Holick MF. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. American Journal of Public Health. February 2006, 96 (2): 252–61. PMC 1470481 . PMID 16380576. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.045260.

- ^ Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. January 2011, 96 (1): 53–8. PMC 3046611 . PMID 21118827. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2704 .

- ^ Gou X, Pan L, Tang F, Gao H, Xiao D. The association between vitamin D status and tuberculosis in children: A meta-analysis. Medicine. August 2018, 97 (35): e12179. PMC 6392646 . PMID 30170465. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012179.

- ^ Keflie TS, Nölle N, Lambert C, Nohr D, Biesalski HK. Vitamin D deficiencies among tuberculosis patients in Africa: A systematic review. Nutrition. October 2015, 31 (10): 1204–12. PMID 26333888. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2015.05.003.

- ^ 道兰氏医学词典中的cholecalciferol

- ^ About Vitamin D. University of California, Riverside. November 2011 [2017-10-15]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-16).

- ^ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Wacker M, Holick MF. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermato-Endocrinology. January 2013, 5 (1): 51–108. PMC 3897598 . PMID 24494042. doi:10.4161/derm.24494.

- ^ 42.0 42.1 Vitamin D3(As Cholecalciferol). HEALTH SOURCES NUTRITION CO., LTD. [2024-10-24].

- ^ Vitashine Vegan Vitamin D3 Supplements. [2013-03-15]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-04).

- ^ Wang T, Bengtsson G, Kärnefelt I, Björn LO. Provitamins and vitamins D2and D3in Cladina spp. over a latitudinal gradient: possible correlation with UV levels. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. September 2001, 62 (1–2): 118–22. PMID 11693362. doi:10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00160-9. (原始内容存档于2012-10-28).

- ^ 45.0 45.1 CHOLECALCIFEROL: A UNIQUE TOXICANT FOR RODENT CONTROL. Proceedings of the Eleventh Vertebrate Pest Conference (1984). University of Nebraska Lincoln. March 1984 [2019-08-27]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-27).

Cholecalciferol is an acute (single-feeding) and/or chronic (multiple-feeding) rodenticide toxicant with unique activity for controlling commensal rodents including anticoagulant-resistant rats. Cholecalciferol differs from conventional acute rodenticides in that no bait shyness is associated with consumption and time to death is delayed, with first dead rodents appearing 3–4 days after treatment.

- ^ Brouwer DA, van Beek J, Ferwerda H, Brugman AM, van der Klis FR, van der Heiden HJ, Muskiet FA. Rat adipose tissue rapidly accumulates and slowly releases an orally-administered high vitamin D dose. The British Journal of Nutrition. June 1998, 79 (6): 527–532. PMID 9771340. doi:10.1079/BJN19980091 .

We investigated the effect of oral high-dose cholecalciferol on plasma and adipose tissue cholecalciferol and its subsequent release, and on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D). ... We conclude that orally-administered cholecalciferol rapidly accumulates in adipose tissue and that it is very slowly released while there is energy balance.

- ^ Pestoff DECAL Possum Bait - Rentokil Initial Safety Data Sheets (PDF). [2020-05-10]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2021-01-15).

- ^ Morgan D. Field efficacy of cholecalciferol gel baits for possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) control. New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 2006, 33 (3): 221–8. S2CID 83765759. doi:10.1080/03014223.2006.9518449.

- ^ Jolly SE, Henderson RJ, Frampton C, Eason CT. Cholecalciferol Toxicity and Its Enhancement by Calcium Carbonate in the Common Brushtail Possum. Wildlife Research. 1995, 22 (5): 579–83. doi:10.1071/WR9950579.

- ^ Kiwicare Material Safety Data Sheet (PDF). (原始内容 (PDF)存档于10 February 2013).

- ^ R. J. Henderson and C. T. Eason (2000), Acute toxicity of cholecalciferol and gliftor baits to the European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Wildlife Research 27(3) 297-300.

- ^ Michael E.Peterson & Kerstin Fluegeman, Cholecalciferol (Topic Review) (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 1, February 2013, Pages 24-27.

- ^ Kocher DK, Kaur G, Banga HS, Brar RS. Histopathological Changes in Vital Organs of House Rats Given Lethal Dose of Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3). Indian Journal of Animal Research. 2010, 2 (3): 193–6. ISSN 0367-6722.

Use of cholecalciferol as a rodenticide in bait lowered the risk of secondary poisoning and minimized the toxicity of non-target species