古希腊少年爱

古希腊少年爱是古希腊时代被当时社会所公开承认的一种社会关系,通常是由一名成年男性和一名青少年组建而成。[2] 这种关系存在于古希腊古风时代和古典希腊时代。[3] 一些学者找到这种关系的仪式起源于克里特岛,这种仪式被认为是进入古希腊军事生活和宙斯宗教的入门仪式。[4]

少年爱这一习俗在古希腊的文化和哲学中是具有理想化和批判性的,[5] 这一习俗并没有在《荷马史诗》中得到体现,它似乎在公元前7世纪前后发展成为古希腊同性社会文化中的一部份。[6] 它的表现特点为:艺术表演和体育比赛中的裸体习俗、贵族阶级的晚婚习俗、交际沙龙和女性的隐居深闺。[7] 少年爱在古希腊的影响十分巨大,以至于成为“自由公民相处关系中的一种文化模式”。[8]

学者们认为按照当时各地的风俗和个人的倾向,这种关系中性行为的角色和程度也会有所不同。[9] 在现代英语词汇中,“Pederasty”通常暗示著未成年人的性虐待行为。但是在当时的雅典法律中,承认“自愿”,但不认为“年龄”是规范性行为的重要因素。[10] 正如研究古典希腊时代的史学家罗宾·奥斯本(Robin Osborne)所指出的那样,用21世纪的道德规范检视历史上的少年爱现象,过于简化问题的复杂性。

| “ | 历史学家的工作在于使人们注意到希腊世界中文学和艺术背后的个人、社会、政治乃至道德问题,同时也在于视人们注意到少年爱及其他一切也是古希腊光荣文化的一部份……历史学家工作的核心价值观在于质疑,而不是去证实。[11] | ” |

相关术语

编辑在希腊语中,“paiderastia(παιδεραστία)”是一个阴性抽象名词,由“paiderastês”变化而来。而“paiderastês”则是由“Pais”(希腊语“孩子”的意思)和“Erastês”(释义见下文)组合而成。[12] 虽然“Pais”这个词汇代表“孩子”的时候并不区分其性别,但是根据亨利·利德尔和Robert Scott所著的《希英词典》的定义,“paiderastia”作为名词表示“男孩们的爱”,作为动词则表示“成为男孩的爱人”。[13]

自从(肯尼斯·丹佛)的经典著作《希腊同性恋》出版以来,“erastês”(爱者)和“erômenos”(被爱者)就成了古希腊少年爱(paiderastia)性爱角色的标准称呼。[14] 这两个词源于希腊语的动词词根“erô”和“erân”(均有“去爱”的含义),其含义可以参见厄洛斯(Eros)。在丹佛严格的二分法中,“erastês(爱者)”被视为关系中年长的一方,他通常处于性爱的主动或主导地位;[15] 而“erômenos(被爱者)”则是关系中年轻的一方,他通常处于性爱的被动或从属地位。需要指出的是,“erômenos”与“paiderastês”不同,后者往往表示一种贬义的“男孩情人”的含义。[16] 另外,“erastês(爱者)”的年龄一般也就是二十出头而已,[17] 因此“erastês(爱者)”和“erômenos(被爱者)”之间的年龄差距并不是很大。[18]

“被爱者”也被称为“孩子”,[19] 他们是未来的公民并应予以指导,而不是“满足性欲的对象”。[20] 这个词语可以理解为父母对自己孩子的爱称,莎孚的诗歌表明这个称呼仅仅是因为年龄的差异而已。[21] 大部份的艺术作品和文学作品表明,“被爱者”的年龄介于13岁到20岁之间,个别案例中有到30岁。众多证据表明一个标准的“被爱者”往往是一个即将开始接受军事训练的年轻贵族,[22] 也就是说他们的年龄应该是在15岁到17岁之间。[23] 作为一个生理成熟的标志,“被爱者”可能与年长的“爱者”一样高,甚至更高。同时他们面部可能已经长出了毛发。[24]

在诗歌和哲学文化中,“被爱者”往往是一个理想化的青年男性。例如古典希腊文化时代的青年雕塑)。[25] 玛莎·努斯鲍姆在其著作《脆弱的慈悲》中,也提出了她对“被爱者”的定义:

| “ | 一个宛若天成的美丽尤物。他明白自己的魅力,因而会对那些渴求他身体的男人表现出冷漠和自私,而对那些欣赏自己的男性则会表示温柔和欣赏。他对“爱者”的善意表示赞赏,对他们的帮助表示感谢。他会同意“爱者”用温柔地抚摸表达他的爱意;而他自己则是那样娴静……通过这个“被爱者”的内心独白,我们可以想像,“被爱者”有著自己的自尊,他们虽然渴望却不会贪婪,他们不愿自己的秘密被看穿却又渴望了解对方的小秘密,仿佛行走在人间的神祇。[26] | ” |

虽然丹佛一直强调“爱者”与“被爱者”的区别就是他们在性爱中的地位,[19] 但是后来的学者都倾向于用更多元化的行为来解释那些体现古希腊少年爱价值观和习俗的作品。虽然古希腊作者在少年爱作品中使用“爱者”和“被爱者”,但是并不是对其社会关系中的地位进行定义。这一点和现代的同性恋或异性恋伴侣有相似之处。[27]

习俗起源

编辑少年爱在古希腊历史晚期忽然突显出来,一枚在克里特岛被发现的约公元前650年到625年制作的黄铜牌匾是迄今有关该习俗的最古老记录。而在接下来的一个世纪里,有关该习俗的记录在古希腊各地的历史文献中被发现,因此有人猜测少年爱这一习俗在希腊的确立应该是公元前五世纪左右。[28]

克里特少年爱作为一种正规的社会制度似乎是以一个启动仪式为基础,而这个启动仪式中涉及了一些诱拐行为。年长的爱者选择被爱者,为被爱者选择朋友,赶走他身边的仰慕者,带他进入正式的社交场合。被爱者如果接受爱者的礼物,则需要与他以朋友的身份共同生活两个月。期间他们会前往乡村狩猎和举办宴会。而在这段时间即将结束的时候,爱者将为被爱者送上三件有特别含义的礼物:军装、牛和水杯。当然,伴随这三件礼物还有其他一些昂贵的礼物。回到城市之后,被爱者将要这头牛献祭给宙斯,并邀请他的朋友来参加这个宴会。而那件军装则象征著被爱者开始进入成年人的世界,将要去建立属于他自己的丰功伟业。而水杯则象征了宙斯和他的侍童伽倪墨得斯之间的故事。因而整个过程代表了克里特少年爱习俗是符合神话传说的。[29]

社会学观点

编辑“爱者-被爱者”关系在古希腊社会和教育系统中发挥了重要作用,其自身复杂的礼仪是当时上层阶级之间的一项重要的社会制度。[30] 此时的少年爱已经被理解为一种教育方式,[31] 从阿里斯托芬到品达(Pindar)的古希腊作家都认为,少年爱是从贵族教育制度里自然产生的。[32] 总的来说,古希腊文学中所描述的少年爱是古希腊自由公民的一种社会制度,被视为一种二元的师生关系。“少年爱作为男性成年的一部份,在古希腊得到了广泛的承认,即便它的作用仍有争议。”[33]

在克里特岛,为了求爱而发生的劫持行为是被容许的,被劫持者的父亲也不得不接受这样的关系。其中在雅典,苏格拉底在色诺芬的沙龙上宣称,“对于一个理想的[34]爱者来说,他父亲无法干涉这个男孩的行为。”[35] 而古希腊的父亲们为了保护儿子不被引诱,他们会任命一些奴隶为“教育者”,以便保护孩子。然而根据埃斯基涅斯(Aeschines)的作品所述,雅典城的父亲们都在祈祷儿子们是英俊和充满魅力的,同时也希望儿子们能充分明白自己将成为雅典其他成年男性所追求的对象,乃至成为“求偶决斗的对象”。[36]

古希腊男孩进入到“爱者-被爱者”关系的年龄范围和古希腊女孩进入婚姻的年龄差不多,而男孩们在成年后会和女孩结婚并成为她们的丈夫。古希腊的男孩们可以自由选择和决定自己的伴侣;而古希腊的女孩的婚姻则被自己的父亲和求婚者控制,他们会根据经济和政治上的原因考量这次联姻。[37] 被爱者与爱者之间的伴侣关系也会为被爱者及其家庭带来好处,例如,会丰富被爱者的社交关系。因此当时的社会也认可一个年轻人拥有多个爱慕者或导师,也许这些导师或爱好者并非那种本质上的“爱者”。通常情况下,爱者和被爱者之间的性关系会在被爱者结婚后结束,但是他们之间的密切关系却会伴随终身。不过对于一些爱者来说,他们会依然和婚后的被爱者保持性关系,用古希腊的俚语说便是,“既然你能举起一头小牛,你自然能举起一头大牛。”[38]

少年爱是同性恋中一种比较理想化的表现形式。当时也有一些不理想的表现形式,例如:男童性奴和卖淫。青年自由公民间的有偿性行为是被禁止的。一旦有青年自由公民提供有偿的性服务,他们将会被社会嘲笑,同时他们在成年后将被剥夺一些公民权利。

即使少年爱在古希腊是合法的,但当时这种关系也有许多失败案例。根据《腓力二世之死》一书所描写,当时许多男孩表示他们“最恨之人往往曾是自己的‘爱者’”。同样的,在克里特岛,被爱者有权宣告他们之间的关系是否合宜,只要有任何暴力行为,被爱者都可以随时宣布终止这段关系。

政治学观点

编辑即便是如少年爱这样被当时习俗所容许的同性性行为也是可以伤害到公众人物的声誉。例如公元前346年,当时的雅典出现了一本名为《反对提尔马科斯的演讲》中,雅典政客埃斯基涅斯(Aeschines)就明确反对另一位经验丰富的中年政客提尔马科斯(Timarchus)进一步升迁,理由是提尔马科斯在年轻的时候曾经当过一个富裕男人的“被爱者”。埃斯基涅斯赢得了他期待的职位,而提尔马科斯则丧失了他的“公民权”(Atimia)。不过埃斯基涅斯也承认自己会和美丽的男孩调情,并为他们写下露骨的情诗。他同时也承认这些事给他带来了一些不利影响,但是他也同时强调这中间并不涉及金钱。

相较之下,保萨尼亚斯(Pausanias)在柏拉图研讨会上表示,少年爱是一种有利于民主而不利于专制的习俗,因为“爱者”与“被爱者”之间的关系远远比被统治者与独裁者之间的关系牢靠。[39][40] 阿特纳奥斯(Athenaeus)说:“耶罗尼米斯说,风华正茂的男孩们团结到一起相互呵护并推翻暴政,这种男孩之间的爱是一种时尚。”他还就此举了几个例子。[41] 而另一些人,比如亚里士多德认为少年爱是一种计画生育手段,克里特岛鼓励人们将性欲转移到非生殖领域,这样可以降低人口的出生比例:

| “ | 立法者提出了许多明智举措,在明面上想办法隔离了女性,这使得男性们不得不考虑与同性结合的可能性。[42] | ” |

哲学观点

编辑苏格拉底与阿尔巴德斯之间的爱情就以回报远比付出多而成为纯洁少年爱的经典例子。在苏格拉底与柏拉图的对话录《斐德罗》中写到:

| “ | 就我所知,对于一个年轻人的最大祝福莫过于希望他能长大的时候有一名品德高尚的年长者相伴,而对于年长者的最大祝福则是希望他能遇到一个爱他的年轻人。我认同这样的原则,爱并非基于血缘、地位或财富而发生。我说什么?荣誉感?这不是任何一个国家或个人能完成的伟大工作……[43] | ” |

艺术表现

编辑希腊花瓶画是现代学者研究古希腊少年爱的一个主要来源。大约数百枚雅典黑彩花瓶上描绘了古希腊少年爱场景。[45] 20世纪初,约翰·毕兹莱(John Beazley)认为现存主要有三类“古希腊少年爱”花瓶:

- “爱者”与“被爱者”面对面站好,爱者屈膝,一只手爱抚被爱者的生殖器,而另一只手则抚摸被爱者的下巴;

- “爱者”向“被爱者”展示他的礼物,有时这个礼物是一只小动物;

- “爱者”与“被爱者”站立并进行股间性爱。[46]

某些传统的爱者给于的礼物有助于理解少年爱中的一些隐喻,例如常见的动物礼物是野兔和公鸡,但若“爱者”提供的动物礼物是鹿或猫科动物,则在暗示“爱者”的身份是一个爱好狩猎的贵族,这有可能成为追求“被爱者”的一个有利因素。[47]

这些作品中一些元素引发了有关“古希腊少年爱”中“爱者”与“被爱者”性爱生活是否和谐的讨论。在这些作品中,年轻的“被爱者”的阴茎从来不会被描绘成勃起状态,他的阴茎“处于疲软状态,即使在某些情况下,要让这些健康青少年的阴茎兴奋起来也是一件慎之又慎的事情”。[48] 爱抚年轻“被爱者”的阴茎是此类花瓶画中描绘求爱题材中的一个非常常见的场景,这样的举动可以参看阿里斯托芬的喜剧作品《鸟》(剧本第142行)。不过有一些花瓶画确实反映了年轻“被爱者”的性反应,这促使一些学者怀疑,“什么促使这些‘爱者’通过观看‘被爱者’的生殖器在他们的手淫下勃起并进而使自己感到愉悦呢?”[49]

一些研究花瓶画年代变化的学者发现,整个古希腊在对待“被爱者”的审美观也是变化的。在大约公元前6世纪的时候,“被爱者”通常是一个年轻的留有胡须和长头发的男性,他有著成年人的身高和体形,通常是裸体;而从公元前5世纪开始,“被爱者”的形象变得越来越小,而且体形也越来也纤细,身体上通常没有体毛,并且他的身边还经常搭配一个女孩。不过有关这个场景的变化和当时社会风俗之间的联系,目前暂时还没有定论。[50]

性爱特征

编辑通过花瓶上的绘画以及一首迷恋被爱者那充满魅力的大腿的诗歌,[51] 现代人可以了解到在古希腊时期,少年爱之间的性行为主要是股间性爱。[52] 为了维护自己的尊严和荣誉,爱者会限制那些渴望自己被爱者的男人以任何形式触碰到他的大腿之间。[53]

肛交在古希腊少年爱的描写中比较少见,但并非没有。但是相关的考古证据不是不够明确就是并非直接证明。但是有些花瓶上会显示这样的场景:爱者坐在那,而他的阴茎则处于勃起状态;而被爱者则靠近或趴在他的腿上。这些类似的场景也在一些异性恋花瓶画上有见到过。[54] 除了一些个人喜好问题之外,肛交也在当时的社会文化中被视为不光彩或可耻的。[55] 一则伊索寓言告诫众人,如果不按照爱神的规定的路线而从后面进入别人的身体是可耻的。哪怕这样的事情只发生一次,那么属于他们之间的爱情就会消失掉。[56] 口交在描述中同样不常见,或并非直接描写。按照现有的史料,肛交和口交似乎是古希腊自由公民和奴隶或男妓才会发生的行为。[57]

丹佛教授坚持认为被爱者在那个时代不会对爱者提出的性需求感到怯弱。[58] 而大卫·赫尔柏林教授则认为男孩之间是不会提出这样的要求的。[59]

诗歌体现

编辑有许多关于“古希腊少年爱”的引用来自古希腊墨伽拉的诗人特奥格拉斯(Theognis of Megara)为基尔罗斯所撰写作品。特奥格拉斯的部分作品可能并不是他个人在墨伽拉所创作,而是代表了“几代人智慧的累积”。这些诗歌反映的是“在特奥格拉斯的自我想像中,将有关社会、政治和道德戒律教导给基尔罗斯是他作为一个墨伽拉成年人应尽的义务”。[60]

特奥格拉斯和基尔罗斯之间的关系脱离了一般分类。虽然基尔罗斯是特奥格拉斯想像出来的一位“被爱者”,但是这些诗歌无疑都是非常明显地向“被爱者”求爱的挑逗情诗。他的一首描写少年爱的诗歌,《悲欢离合》(The Joys and Sorrows)[61] 很好地描述了很多“爱者”的心态,“情可追忆,唯留惘然”(the relationship, in any case, is left vague)。[62]

特奥格拉斯描写了一场在待克里夫墓地附近举行的,以友谊而闻名的青少年接吻大赛。他说,在那个时候称呼他们为伽倪墨得斯是准确的。[63]

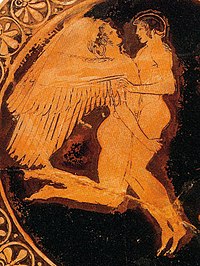

神话及宗教

编辑古希腊神话中,宙斯掠走伽倪墨得斯被认为是古希腊少年爱的开端,特奥格拉斯在跟他们说道:

| “ | 这儿有一个故事,描述了爱上少年的快乐。克洛诺斯的儿子,众神之王宙斯发现他爱上了伽倪墨得斯。于是他抓走了他,将他囚禁在奥林匹斯山。为了让他保持如鲜花绽放般的美丽少年模样,他赋予了伽倪墨得斯神格……所以,不用怀疑,西蒙尼特斯,我发现我也深深地对一个英俊男孩著迷。[64] | ” |

古希腊神话中至少有50个少年男性被众神仰慕的故事,这些少年分别成为了宙斯、波塞冬、阿波罗、奥菲斯、赫拉克勒斯、狄俄倪索斯、赫耳墨斯或潘的娈童。在希腊诸男性神祇中,除了战神阿瑞斯之外都有少年爱的描写。按照一些学者的研究,这种描写代表了少年爱在古希腊启蒙时代的重要性。[65]

区域特征

编辑希腊东部地区

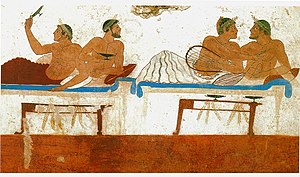

编辑在爱奥尼亚和埃俄利亚(Aeolia)的一些少年爱习俗特色可以在阿克那里翁(Anacreon)和阿乐凯奥斯(Alcaeus)的诗作中看到。一个男人因为的勇敢和政治上的成熟而被人们赞誉,他的行为组成了斯克里亚(skolia)的象征,并逐渐成为整个大陆的习俗。不像希腊中南部的多里安人(Dorian),那里的“爱者”通常终生只会有一个“被爱者”;而在爱奥尼亚和埃尔利亚,“爱者”的一生常常与多个“被爱者”一起度过。从阿乐凯奥斯的诗歌中我们得知,希腊东部的“爱者”们会经常邀请“被爱者”共进晚餐。[67]

斯巴达地区

编辑斯巴达,多里安城邦之一,被认为是首个举行裸体竞技运动会的城市和首批承认少年爱合法的古希腊城邦之一。[68] 斯巴达人认为,一个成熟有阅历并且充满造诣的贵族是一个年轻人成长成为自由公民的重要帮助力量。因此统治阶级的教育要求斯巴达所有贵族、自由公民之间必须有“少年爱”关系。[69] “爱者”负责年轻的“被爱者”的培训。在这里,“少年爱”和军事训练紧密相联。这一点,在斯巴达及其他古希腊地区都有体现。在雅典与斯巴达的战争中,[70] 每场战斗开始前,他们都会向爱神厄洛斯祭祀。

这种关系的性质在当时也是有争议的。色诺芬在他的作品《斯巴达宪法》(Constitution of the Lacedaimonians)中强调斯巴达男人和男孩之间的关系应该只是纯洁的“理想上志同道合的朋友关系”,而不应该包括性行为。如果他们之间仅仅存在性吸引,那么这种关系与乱伦一样可憎。[71] 普鲁塔克则指出,当斯巴达男孩到了青春期时,就可以和年长的男性发生性关系。[72] 学者伊良(Aelian)也有部分著作涉及斯巴达,他指出一个人如果没有年轻的“被爱者”,那么就会被视为有性格上的缺陷。即便他是优秀的,但还是会被认为有一处没有做好。[73] 但是伊良同时也指出,如果“爱者”和“被爱者”沉迷肉欲则会被视为对斯巴达荣誉的侮辱,那么他们将不得不面临选择,要么被流放,要么以流血牺牲来赎罪忏悔。[74]

墨伽拉地区

编辑墨伽拉与斯巴达关系十分友好,因而在文化上也收到了斯巴达的影响,因而在风俗和法律上会效仿斯巴达。大约在公元前七世纪,墨伽拉也宣布了少年爱的合法地位。[75] 同时紧跟著斯巴达,墨伽拉也大力提倡裸体竞技运动会。墨伽拉是赛跑运动员奥西普斯(Orsippus)的家乡,他是第一个在古代奥运会赛跑比赛中裸体跑步的运动员,也是“第一个被全希腊加冕的裸体冠军”。[76][77] 墨伽拉的诗人特奥格拉斯在诗歌里写道裸体运动是少年爱的前戏,“白天的快乐就是裸著身体运动;夜间的愉悦则是与美丽的男孩而眠”。

雅典地区

编辑与其他地区一样,古代雅典的少年爱最早是在贵族之间流行,很快就普及到自由公民。古代雅典的陶器是现代学者了解当时少年爱风俗的重要考古来源,[78] 陶器上描绘的青少年年纪从12岁到18岁不等。[79] 一些古代雅典的法律规范了少年爱的关系。

玻俄提亚地区

编辑底比斯地区的主要城邦便是玻俄提亚(Boeotia),以其“少年爱”的做法而闻名,其主要传统就是在城市里所创造的神话。例如:拉伊俄斯(Laius),底比斯传说中的创立者,他背叛了他的父亲,同时又强奸了他的儿子。另一个著名的底比斯神话人物便是纳西瑟斯。

根据普鲁塔克的说法,底比斯地区的少年爱是作为一种对未成年人的教育方式而存在。少年爱教导青少年们“从年轻时的软弱变得勇敢”,同时“锻炼青少年们的举止和性格”。[80] 底比斯圣队,这是由150对少年爱恋人所组成的战斗营,他们在公元前338年与马其顿国王腓力二世在喀罗尼亚(Chaeronea)的战斗中,他们战至最后一人。

玻俄提亚地区的陶器与雅典地区的陶器相比,并没有发现具有约翰·毕兹莱所描述的三种少年爱场景特征。在迄今被发现的有限的玻俄提亚陶器中,可以发现已经减少了有关当时少年爱风俗场景的作品。[81]

现代学术研究

编辑直到19世纪末,现代的学者们才开始探讨古代希腊社会,例如:雅典、底比斯、克里特岛、斯巴达、厄利斯及其他地区的道德观。在首批提出探讨的学者中,约翰·阿丁顿·西蒙兹(John Addington Symonds)做出了开创性的贡献,他在1873年写出了《一个有关古希腊伦理的问题》(A Problem in Greek Ethics)一书。由于作者本人的版权要求,这本书在1883年仅仅小范围地发行了10本。直到1901年,这本著作才以修订的形式正式出版。[82] 爱德华·卡朋特(Edward Carpenter)扩大了西蒙兹的研究对象,在他1914年出版的著作《原始民族的中间形态》(Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk)中,他研究探讨了全球所有文化中的同性恋风俗,而不仅仅是古希腊少年爱。[83] 在德国,古典希腊研究学者保罗·勃兰特(Paul Brandt)化名汉斯·李希特(Hans Licht)在1932年出版了《古希腊时代的性生活》(Sexual Life in Ancient Greece)一书。

然而在古希腊研究的主流做法中,都特意忽视了对同性恋文化的研究。E·M·福斯特在其1910年出版的小说《墨利斯的情人》就描写了一个剑桥大学的古希腊文化教授指著一本古希腊文本对他的学生说,“有关古希腊那些不可告人的色情内容都被隐瞒了”。在20世纪40年代,H·马歇尔(H. Mitchell )写道,“古希腊在道德方面是很特殊的,但是为了我们的和谐,过于密切的窥探变得有些不需要了”。直到肯尼斯·丹佛(Kenneth Dover)在1978年出版了他的著作《希腊同性恋史》(Greek Homosexuality)之后,有关这方面的讨论才变得公开和广泛起来。

参考文献

编辑- ^ J.D. Beazley, "Some Attic Vases in the Cyprus Museum", Proceedings of the British Academy 33 (1947); p.199; Dover, Greek Homosexuality, pp. 94-96.

- ^ C.D.C. Reeve, Plato on Love: Lysis, Symposium, Phaedrus, Alcibiades with Selections from Republic and Laws (Hackett, 2006), p. xxi online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective, translated by Kirsi Stjerna (Augsburg Fortress, 1998, 2004), p. 57 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Nigel Blake et al., Education in an Age of Nihilism (Routledge, 2000), p. 183 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, p. 57; William Armstrong Percy III, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," in Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West (Binghamton: Haworth, 2005), p. 17. Sexual variety, not excluding paiderastia, was characteristic of the Hellenistic era; see Peter Green, "Sex and Classical Literature," in Classical Bearings: Interpreting Ancient Culture and History (University of California Press, 1989, 1998), p. 146 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Robert B. Koehl, "The Chieftain Cup and a Minoan Rite of Passage," Journal of Hellenic Studies 106 (1986) 99–110, with a survey of the relevant scholarship including that of Arthur Evans (p. 100) and others such as H. Jeanmaire and R.F. Willetts (pp. 104–105); Deborah Kamen, "The Life Cycle in Archaic Greece," in The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece (Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 91–92. Kenneth Dover, a pioneer in the study of Greek homosexuality, rejects the initiation theory of origin; see "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation," in Que(e)rying Religion: A Critical Anthology (Continuum, 1997), pp. 19–38. For Dover, it seems, the argument that Greek paiderastia as a social custom was related to rites of passage constitutes a denial of homosexuality as natural or innate; this may be to overstate or misrepresent what the initiatory theorists have said. The initiatory theory does not claim to account for the existence of homosexuality, but for formal paiderastia.

- ^ For examples, see Kenneth Dover, Greek Homosexuality (Harvard University Press, 1978, 1898), p. 165, note 18, where the eschatological value of paiderastia for the soul in Plato is noted; Paul Gilabert Barberà, "John Addington Symonds. A Problem in Greek Ethics. Plutarch's Eroticus Quoted Only in Some Footnotes? Why?" in The Statesman in Plutarch's Works (Brill, 2004), p. 303 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); and the pioneering view of Havelock Ellis, Studies in the Psychology of Sex (Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1921, 3rd ed.), vol. 2, p. 12 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) For Stoic "utopian" views of paiderastia, see Doyne Dawson, Cities of the Gods: Communist Utopias in Greek Thought (Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 192 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Thomas Hubbard, "Pindar's Tenth Olympian and Athlete-Trainer Pederasty," in Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity, pp. 143 and 163 (note 37), with cautions about the term "homosocial" from Percy, p. 49, note 5.

- ^ Percy, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," p. 17 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) et passim.

- ^ Dawson, Cities of the Gods, p. 193. See also George Boys-Stones, "Eros in Government: Zeno and the Virtuous City," Classical Quarterly 48 (1998), 168–174: "there is a certain kind of sexual relationship which was considered by many Greeks to be very important for the cohesion of the city: sexual relations between men and youths. Such relationships were taken to play such an important role in fostering cohesion where it mattered — among the male population — that Lycurgus even gave them official recognition in his constitution for Sparta" (p. 169).

- ^ Michael Lambert, "Athens," in Gay Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia (Taylor & Francis, 2000), p. 122.

- ^ See Osborne following. Gloria Ferrari, however, notes that there were conventions of age pertaining to sexual activity, and if a man violated these by seducing a boy who was too young to consent to becoming an eromenos, the predator might be subject to prosecution under the law of hubris; Figures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece (University of Chicago Press, 2002), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Robin Osborne, Greek History (Routledge, 2004), pp. 12 online and 21.

- ^ Etymologies (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) in American Heritage Dictionary, Random House Dictionary, and Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940 9th ed., with 1968 supplement in 1985 reprinting), p. 1286.

- ^ The pair of terms are used both within and outside the field of classical studies. For surveys and reference works within the study of ancient culture and history, see for instance The World of Athens: An Introduction to Classical Athenian Culture, a publication of the Joint Association of Classical Teachers (Cambridge University Press, 1984, 2003), pp. 149–150 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); John Grimes Younger, Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z pp. 91–92 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Outside classical studies, see for instance Michael Burger, The Shaping of Western Civilization: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment (University of Toronto Press, 2008), pp. 50–51 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Richard C. Friedman and Jennifer I. Downey, Sexual Orientation and Psychoanalysis: Sexual Science and Clinical Practice (Columbia University Press, 2002), pp. 168–169 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Michael R. Kauth, True Nature: A Theory of Sexual Attraction (Springer, 2000), p. 87 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Roberto Haran, Lacan's Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (2004), p. 165ff. online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Kenneth Dover, Greek Homosexuality (Harvard University Press, 1978, 1989), p. 16.

- ^ Liddell and Scott, Greek-English Lexicon, p. 1286.

- ^ William Armstrong Percy III, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece (University of Illinois Press, 1996), p. 1 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Martha Nussbaum, "Platonic Love and Colorado Law: The Relevance of Ancient Greek Norms to Modern Sexual Controversies," Sex and Social Justice (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 309: "because the popular thought of our day tends to focus on the scare image of a 'dirty old man' hanging around outside the school waiting to molest young boys, it is important to mention, as well, that the erastês might not be very far in age from the erômenos."

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Dover, Greek Homosexuality, p. 16.

- ^ Marguerite Johnson and Terry Ryan, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2005), p. 4 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ It is uncertain whether the pais Kleis is Sappho's actual daughter, or whether the word is affectionate. Anne L. Klinck, "'Sleeping in the Bosom of a Tender Companion': Homoerotic Attachments in Sappho," in Same-sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West (Haworth Press, 2005), p. 202 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Jane McIntosh Snyder, The Woman and the Lyre (Southern Illinois University Press, 1989), p. 3 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) The word pais can also be used of a bride; see Johnson and Ryan, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society, p. 80, note 4.

- ^ "We can conclude that the erômenos is generally old enough for mature military and political action": Nussbaum, "Platonic Love and Colorado Law," p. 309 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ See especially Mark Golden, endnote to "Slavery and Homosexuality at Athens: Age Differences between erastai and eromenoi," in Homosexuality in the Ancient World (Taylor & Francis, 1992) pp. 175–176 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); also Johnson and Ryan, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Culture, p. 3; Barry S. Strauss, Fathers and Sons in Athens: Ideology and Society in the Era of the Peloponnesian War (Routledge, 1993), p. 30 online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆); Martha Nussbaum, "Eros and the Wise: The Stoic Response to a Cultural Dilemma," Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 13 (1995, 2001), p. 230 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Nuances of age also discussed by Ferrari, Figures of Speech, pp. 131–132 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Dover, Greek Homosexuality, pp. 16 and 85; Ferrari, Figures of Speech, p. 135.

- ^ Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, p. 61, considers the kouroi to be examples of pederastic art. "The particular attributes that kouroi display match those of such 'beloveds' in the visual and literary sources from the late archaic to the classical age": Deborah Tam Steiner, Images in Mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and Thought (Princeton University Press, 2001), p. 215 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) The presence of facial and pubic hair on some kouroi disassociates them with the erômenos if the latter is taken only as a boy who has not entered adolescence; thus Jeffrey M. Hurwit, "The Human Figure in Early Greek Sculpture and Vase-Painting," in The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 275 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Martha Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness: (Cambridge University Press, 1986, 2001), p. 188 online.

- ^ Dover, "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation," pp. 19–20, notes the usage of "the same words for homosexual as for heterosexual emotion … and the same for its physical consummation" from the archaic period on.

- ^ Dover, pp. 205-7

- ^ The main source for this rite of initiation is Strabo 10.483–484, quoting Ephoros; the summary given here is the construction of Robert B. Koehl, "The Chieftain Cup and a Minoan Rite of Passage," Journal of Hellenic Studies 106 (1986), pp. 105–107.

- ^ John Pollini, "The Warren Cup: Homoerotic Love and Symposial Rhetoric in Silver," Art Bulletin 81.1 (1999) 21–52.

- ^ Blake et al., Education in an Age of Nihilism, p. 183.

- ^ Gregory Nagy, "Early Greek Views of Poets and Poetry," in The Cambridge History of Literary Criticis: Classical Criticism (Cambridge University Press, 1989, 1997), p. 40 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Johnston, Sarah Iles. Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004. pg. 446; see also Cocca, Carolyn. Adolescent Sexuality: A Historical Handbook and Guide. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2006. pg. 4

- ^ The term here rendered as "ideal" is καλοκἀγαθίᾳ, translated as "a perfect man, a man as he should be" in Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford, 1968; p.397)

- ^ Xenophon, Symposium; VIII.11

- ^ Victoria Wohl, Love among the Ruins: The Erotics of Democracy in Classical Athens p.5 referring to Aeschines, (Tim.134)

- ^ A Henri Irénée Marrou, George Lamb, History of Education in Antiquity p.27

- ^ Andrew Calimach, Lovers' Legends: The Gay Greek Myths

- ^ Clifford Hindley, "Debate: Law, Society and Homosexuality in Classical Athens" in Past and Present, 133 (1991), p. 167n4.

- ^ Plato Symposium 182c.

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, 602

- ^ Aristotle, Politics 2.1272a 22-24

- ^ Plato, Phaedrus in the Symposium

- ^ Plato, Laws, 636D & 835E

- ^ Deborah Kamen, "The Life Cycle in Archaic Greece," in The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 91 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Beazley as summarized by Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, p. 119.

- ^ Judith M. Barringer, The Hunt in Ancient Greece (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), pp. 70–72 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, p. 188; see also Dover, Greek Homosexuality, p. 96; Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, p. 119.

- ^ Thomas Hubbard, review of David Halperin's How to Do the History of Homosexuality (2002), Bryn Mawr Classical Review 22 September 2003 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Ferrari, Figures of Speech, p. 140; Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, pp. 119–120.

- ^ For examples, see Johnson and Ryan, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society, p. 116, note 4, quoting a fragment from Solon: "a man falls in love with a youth in the full-flower of boy-love / possessed of desire-enhancing thighs and a honey-sweet mouth"; Nussbaum, Sex and Social Justice, p. 450, note 48, quoting a fragment of the lost Myrmidons of Aeschylus in which Achilles mourns the dead Patroclus, their "many kisses," and the "god-fearing converse with your thighs."

- ^ Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, p. 119; Nussbaum, Sex and Social Justice, pp. 268, 307, 335; Ferrari, Figures of Speech, p. 145.

- ^ Ferrari, Figures of Speech, p. 145.

- ^ Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Ancient Greece, p. 119.

- ^ Nussbaum, Sex and Social Justice, pp. 268, 335; Ferrari, Figures of Speech, p. 145.

- ^ Aesop, "Zeus and Shame" (Perry 109, Chambry 118, Gibbs 528), in Fables.

- ^ Johnson and Ryan, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature, p. 3, based on Attic red-figure pottery; Percy, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Ancient Greece, p. 119.

- ^ Dover, Greek Homosexuality[来源请求]

- ^ David M. Halperin, How to Do the History of Homosexuality (University of Chicago Press, 2002).[来源请求]

- ^ Thomas K. Hubbard, Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a sourcebook of basic documents in translation, University of California, 2003; p.23

- ^ Theognis, 2.1353–56.

- ^ Robert Lamberton, Hesiod (Yale University Press, 1988), p. 26 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Theocritus, Idyll XII.

- ^ Theognidean corpus 1345–50, as cited by Kamen, "The Life Cycle in Archaic Greece," p. 91. Although the speaker is identified here conventionally as Theognis, certain portions of the work attributed to him may not be by the Megaran poet.

- ^ Sergent, Homosexuality and Greek Myth, passim

- ^ Dover, "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation,"passim, especially pp. 19–20, 22–23.

- ^ Percy, William A. Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, pp146-150

- ^ Thomas F. Scanlon, "The Dispersion of Pederasty and the Athletic Revolution in Sixth-Century BC Greece," in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, pp. 64-70.

- ^ Erich Bethe,Die Dorische Knabenliebe: ihre Ethik und ihre Ideen, 1907, 441, 444

- ^ Athenaeus of Naucratis, The Deipnosophists, XIII: Concerning Women

- ^ 色诺芬, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, 2.13 : "The customs instituted by Lycurgus were opposed to all of these. If someone, being himself an honest man, admired a boy's soul and tried to make of him an ideal friend without reproach and to associate with him, he approved, and believed in the excellence of this kind of training. But if it was clear that the attraction lay in the boy's outward beauty, he banned the connexion as an abomination; and thus he caused lovers to abstain from boys no less than parents abstain from sexual intercourse with their children and brothers and sisters with each other." online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 17.1: "When the boys reached this age, they were favoured with the society of lovers from among the reputable young men. The elderly men also kept close watch of them, coming more frequently to their places of exercises, and observing their contests of strength and wit, not cursorily, but with the idea that they were all in a sense the fathers and tutors and governors of all the boys. In this way, at every fitting time and in every place, the boy who went wrong had someone to admonish and chastise him."

- ^ Aelian, Historical Miscellany 3.10 p.135; Loeb, 1997

- ^ Aelian, Var. Hist., III.12

- ^ N.G.L. Hammond, A history of Greece to 322 BC, 1989; p.150

- ^ W. Sweet, Sport and Recreation in Ancient Greece, 1987; p.125

- ^ Pausanias, 1.44.1

- ^ Rommel Mendès-Leite et al. Gay Studies from the French Cultures p.157; Percy, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," pp. 30-31.

- ^ Percy, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," p. 54.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pelopidas, 19.1: "Speaking generally, however, it was not the passion of Laius that, as the poets say, first made this form of love customary among the Thebans; but their law-givers, wishing to relax and mollify their strong and impetuous natures in earliest boyhood, gave the flute great prominence both in their work and in their play, bringing this instrument into preeminence and honour, and reared them to give love a conspicuous place in the life of the palaestra, thus tempering the dispositions of the young men."

- ^ Charles Hupperts, "Boeotian Swine: Homosexuality in Boeotia" in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity, p. 190 online. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ A Problem in Greek Ethics Index. [2012-04-15]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-12).

- ^ Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk Index. [2012-04-15]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-25).

参见条目

编辑延伸阅读

编辑- Dover, Kenneth J. Greek Homosexuality. Duckworth 1978.

- Dover, Kenneth J. "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation." In Que(e)rying Religion: A Critical Anthology. Continuum, 1997, pp. 19–38.

- Ellis, Havelock. Studies in the Psychology of Sex, vol. 2: Sexual Inversion. Project Gutenberg text (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Ferrari, Gloria. FIgures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece. University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- Hubbard, Thomas K. Homosexuality in Greece and Rome. University of California Press, 2003.[1]

- Johnson, Marguerite, and Ryan, Terry. Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook. Routledge, 2005.

- Lear, Andrew, and Eva Cantarella. Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys Were Their Gods. Routledge, 2008. ISBN 978-0415223676.

- Nussbaum, Martha. Sex and Social Justice. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Percy, William A. Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

- Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West. Binghamton: Haworth, 2005.

- Sergent, Bernard. Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Beacon Press, 1986.