卡維地洛

卡維地洛(英語:Carvedilol)以Coreg等商品名於市面販售,是種用於治療高血壓、鬱血性心臟衰竭 (CHF) 和左心室功能障礙的藥物。[1]此藥物於治療高血壓時通常是作為一種二線藥物。[1]

| |

| |

| 臨床資料 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Coreg及其他 |

| 其他名稱 | BM-14190 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697042 |

| 核准狀況 | |

| 給藥途徑 | 口服給藥 |

| ATC碼 | |

| 法律規範狀態 | |

| 法律規範 |

|

| 藥物動力學數據 | |

| 生物利用度 | 25–35% |

| 血漿蛋白結合率 | 98% |

| 藥物代謝 | 肝臟 (細胞色素CYP2D6及CYP2C9) |

| 生物半衰期 | 7–10小時 |

| 排泄途徑 | 尿液 (16%), 糞便 (60%) |

| 識別資訊 | |

| |

| CAS號 | 72956-09-3 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB配體ID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.117.236 |

| 化學資訊 | |

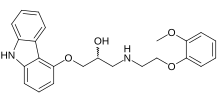

| 化學式 | C24H26N2O4 |

| 摩爾質量 | 406.48 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| 手性 | 外消旋體 |

| |

| |

使用後常見的副作用有頭暈、疲倦、關節痛、低血壓、噁心和呼吸困難。[1]嚴重的副作用有支氣管痙攣。[1]個體於懷孕期間使用對於胎兒的安全,或個體進行母乳哺育時對於嬰兒的安全尚未有充分的數據以供研究。[2]不建議罹患肝病的人使用。[3]卡維地洛是一種非選擇性β受體阻滯劑,並具有選擇性α-1受體阻滯劑的活性。[1]此藥物發生作用的機制尚未被完全了解,但涉及的可能是血管舒張的結果。[1]

卡維地洛於1978年獲得專利,並於1995年被美國食品藥物管理局(FDA)核准作醫療用途。[1][4]它已被列入世界衛生組織基本藥物標準清單中。[5]目前市面上有通用名藥物販售。[1]它於美國2021年最常使用處方藥中排名第26,開立的處方箋數量超過2,100萬張。[6][7]

醫療用途

編輯卡維地洛適用於鬱血性心臟衰竭 (CHF)的治療,通常作為血管張力素轉化酶抑制劑 (ACE抑制劑) ,及利尿劑的輔助藥物。臨床證明它可降低CHF患者的死亡率和住院率。[8]卡維地洛治療心臟衰竭的機制在於它能抑制交感神經系統中的受體(此系統會釋放正腎上腺素至全身,包括心臟)。[9]正腎上腺素是一種可使心臟跳動更快、更努力運作的激素。[9]阻斷正腎上腺素與心臟中受體的結合可導致血管舒張,降低心率和血壓,並改善心肌收縮力,[10]最終把心臟的負荷降低。[9]

卡維地洛可降低心臟病發作後患者因心臟功能下降而致的死亡、住院和心臟病復發的風險。[11][12]卡維地洛也被證明可減少嚴重心臟衰竭患者的死亡和住院率。[13]

卡維地洛在一般醫療過程中已被用於治療單純性高血壓,但研究顯示它與其他降血壓藥物或是其他β受體阻滯劑相比,降血壓的效果會相對較低。[14]

卡維地洛也具有預防肝硬化患者因食道靜脈曲張發生流血的功效。[15]

配方形式

編輯卡維地洛的配方形式有:

禁忌症

編輯患有支氣管氣喘或支氣管痙攣的患者不應使用卡維地洛,因為此藥物會升高支氣管收縮的風險。[18][19]患有二度或三度房室傳導阻滯、竇房結功能障礙(心臟傳導疾病 )、嚴重心跳過緩(除非個體安裝有永久性心律調節器)或失代償性心臟病(即心臟衰竭)的患者也不應使用此藥物。有嚴重肝功能損害的患者應謹慎使用。[20][21][22]

副作用

編輯卡維地洛導致的副作用中最常見的(發生率 >10%)有:[16]

不建議患有惡化型支氣管痙攣疾病(例如目前有氣喘症狀)的人使用卡維地洛,因為它會阻斷有助於打開氣道的受體。[16]

卡維地洛可能會將低血糖症狀掩蓋,[16]導致糖尿病低血糖症發生卻不自覺的情況(低血糖無自覺症狀)。這情況被稱為β受體阻滯劑引起的低血糖無自覺症狀。糖尿病低血糖症是指糖尿病患者的血糖水平低於正常範圍(低血糖),它是急診室和醫院最常遇到的低血糖原因之一。根據美國國家電子傷害監測系統 - 全方位傷害程序 (National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program, NEISS-AIP) 的數據,美國在2004年至2005年之間抽樣調查的案例中,估計有55,819起病例 (佔總住院人數的8.0%) 與胰島素使用有關聯,其中嚴重低血糖症可能是最常見的一種結果。[23]

與其他藥物交互作用

編輯如果將此藥物與胺碘酮、地高辛、地爾硫䓬、伊伐布雷定或維拉帕米一起使用,會增加心跳過慢的風險。[24]此外,卡維地洛與非1,4-二氫吡啶類鈣通道阻滯劑(包括地爾硫䓬和維拉帕米)組合使用,可增強其心臟抑制作用。[24]

藥理學

編輯藥效學

編輯卡維地洛既是一種非選擇性β受體阻滯劑(β1與β2),也是一種選擇性α-1受體阻滯劑(α1)。[1]

卡維地洛可阻斷α-1受體,導致血管舒張。這種抑制作用造成周邊血管阻力降低,而產生抗高血壓作用。由於卡維地洛會阻斷心臟中的β1受體,而停止產生反射性心跳過速反應。[25]

藥物動力學

編輯口服卡維地洛後,由於廣泛的首過代謝,藥物的生物利用度約為25%至35%。飲食期間服用會將藥物吸收減慢,但生物利用度無顯著差異。給藥期間同時進食可降低姿位性低血壓的風險。[16]

大部分卡維地洛與血漿蛋白結合(主要是人類血清白蛋白),可達98%。卡維地洛是一種脂溶性藥物,在動物實驗中容易穿過血腦屏障。因此它不像是一些只會作用於外周組織(人體中樞神經系統以外的所有組織和器官)的藥物。[26][27]

參考文獻

編輯- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Carvedilol Monograph for Professionals. Drugs.com. AHFS. [2018-12-24]. (原始內容存檔於2011-01-20).

- ^ Carvedilol Use During Pregnancy. Drugs.com. [2018-12-24]. (原始內容存檔於2009-12-23).

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 76 76. Pharmaceutical Press. 2018: 147. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR. Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006: 463. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. hdl:10665/345533 . WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ The Top 300 of 2021. ClinCalc. [2024-01-14]. (原始內容存檔於2024-01-15).

- ^ Carvedilol - Drug Usage Statistics. ClinCalc. [2024-01-14]. (原始內容存檔於2020-04-11).

- ^ Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, Wilkoff BL. 2013 AHA Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure (PDF). Circulation. 2013-10-15, 128 (16): e240–327 [2024-05-17]. PMID 23741058. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-01-14). 已忽略未知參數

|collaboration=(幫助) - ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ogbru O. Shiel Jr WC , 編. carvedilol (Coreg): Heart Failure, Side Effects, Uses & Dosage. MedicineNet. 4 November 2022 [2024-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2024-05-01) (英語).

- ^ Kubon C, Mistry NB, Grundvold I, Halvorsen S, Kjeldsen SE, Westheim AS. The role of beta-blockers in the treatment of chronic heart failure. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. April 2011, 32 (4): 206–212. PMID 21376403. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2011.01.006.

- ^ Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. May 2001, 357 (9266): 1385–1390. PMID 11356434. S2CID 1840228. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04560-8.

- ^ Huang BT, Huang FY, Zuo ZL, Liao YB, Heng Y, Wang PJ, Gui YY, Xia TL, Xin ZM, Liu W, Zhang C, Chen SJ, Pu XB, Chen M, Huang DJ. Meta-Analysis of Relation Between Oral β-Blocker Therapy and Outcomes in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. The American Journal of Cardiology. June 2015, 115 (11): 1529–1538. PMID 25862157. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.02.057.

- ^ Cleland JG, Bunting KV, Flather MD, Altman DG, Holmes J, Coats AJ, Manzano L, McMurray JJ, Ruschitzka F, van Veldhuisen DJ, von Lueder TG, Böhm M, Andersson B, Kjekshus J, Packer M, Rigby AS, Rosano G, Wedel H, Hjalmarson Å, Wikstrand J, Kotecha D. Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials. European Heart Journal. January 2018, 39 (1): 26–35. PMC 5837435 . PMID 29040525. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx564.

- ^ Wong GW, Laugerotte A, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of dual alpha and beta blockers for primary hypertension. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. August 2015, 2015 (8): CD007449. PMC 6486308 . PMID 26306578. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007449.pub2.

- ^ Reiberg, T, Ulbrich, G, et al. Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol. Gut. November 2013, 62 (11): 1634–1641. PMID 23250049. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304038 .

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Coreg - Food and Drug Administration (PDF). [2024-05-17]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-03-04).

- ^ Drug Approval Package. www.accessdata.fda.gov. [2015-11-05]. (原始內容存檔於2015-08-10).

- ^ Morales DR, Lipworth BJ, Donnan PT, Jackson C, Guthrie B. Respiratory effect of beta-blockers in people with asthma and cardiovascular disease: population-based nested case control study. BMC Medicine. January 2017, 15 (1): 18. PMC 5270217 . PMID 28126029. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0781-0 .

- ^ Kotlyar E, Keogh AM, Macdonald PS, Arnold RH, McCaffrey DJ, Glanville AR. Tolerability of carvedilol in patients with heart failure and concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. December 2002, 21 (12): 1290–5. PMID 12490274. doi:10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00459-x.

- ^ Sinha R, Lockman KA, Mallawaarachchi N, Robertson M, Plevris JN, Hayes PC. Carvedilol use is associated with improved survival in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites (PDF). Journal of Hepatology. July 2017, 67 (1): 40–46. PMID 28213164. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.005. hdl:20.500.11820/7afe3b88-1064-4da1-927e-4d4e867387eb.

- ^ Zacharias AP, Jeyaraj R, Hobolth L, Bendtsen F, Gluud LL, Morgan MY. Carvedilol versus traditional, non-selective beta-blockers for adults with cirrhosis and gastroesophageal varices. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. October 2018, 2018 (10): CD011510. PMC 6517039 . PMID 30372514. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011510.pub2.

- ^ Lo GH, Chen WC, Wang HM, Yu HC. Randomized, controlled trial of carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. November 2012, 27 (11): 1681–7. PMID 22849337. S2CID 23494154. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07244.x.

- ^ Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. October 2006, 296 (15): 1858–66. PMID 17047216. doi:10.1001/jama.296.15.1858.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 Koshman SL, Paterson I. Heart Failure. Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPS). 2023-03-15 [2024-04-29].

- ^ Ruffolo RR, Gellai M, Hieble JP, Willette RN, Nichols AJ. The pharmacology of carvedilol. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1990, 38 (Suppl 2): S82–S88. PMID 1974511. S2CID 2901620. doi:10.1007/BF01409471.

- ^ Wang J, Ono K, Dickstein DL, Arrieta-Cruz I, Zhao W, Qian X, Lamparello A, Subnani R, Ferruzzi M, Pavlides C, Ho L, Hof PR, Teplow DB, Pasinetti GM. Carvedilol as a potential novel agent for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. December 2011, 32 (12): 2321.e1–12. PMC 2966505 . PMID 20579773. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.004.

- ^ Bart J, Dijkers EC, Wegman TD, de Vries EG, van der Graaf WT, Groen HJ, Vaalburg W, Willemsen AT, Hendrikse NH. New positron emission tomography tracer [(11)C]carvedilol reveals P-glycoprotein modulation kinetics. Br J Pharmacol. August 2005, 145 (8): 1045–51. PMC 1576233 . PMID 15951832. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706283.

延伸閱讀

編輯- Chakraborty S, Shukla D, Mishra B, Singh S. Clinical updates on carvedilol: a first choice beta-blocker in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. February 2010, 6 (2): 237–50. PMID 20073998. S2CID 25670550. doi:10.1517/17425250903540220.

- Dean L. Carvedilol Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype. Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al (編). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 2018 [2024-05-17]. PMID 30067327. Bookshelf ID: NBK518573. (原始內容存檔於2020-10-26).