印度尼西亞大屠殺 (1965年—1966年)

此條目可參照英語維基百科相應條目來擴充。 (2018年9月30日) |

1965-1966年的印度尼西亞大屠殺(印尼語:Pembunuhan Massal Indonesia & Pembersihan G.30.S/PKI),也稱為印度尼西亞種族滅絕、印度尼西亞反共大清洗,是指發生在印度尼西亞,在美國以及其它西方國家的支持下,受印尼軍隊及政府的煽動,針對當地印度尼西亞共產黨成員、共產主義同情者、婦女組織格瓦尼(Gerwani)成員、工會會員、爪哇族阿邦甘(Abangan)、印尼華人、無神論者、左翼分子的大屠殺以及城市暴動。此次大屠殺開始於一次有爭議的共產主義者的政變,即九三〇事件後,反共者針對共產主義者的肅清。據估算,事件的受害者約為50萬到100萬,部分來源的數據高達200到300萬。大清洗發生在全球冷戰的背景之下,是對共產主義者和親共者的政治清算,也是印尼政府由舊秩序邁向新秩序的關鍵推動事件。此次事件導致了蘇加諾的下台,開啟了蘇哈托為期三十多年的威權獨裁統治。

| 1965年-1966年印度尼西亞大屠殺 | |

|---|---|

| 冷戰的一部分 | |

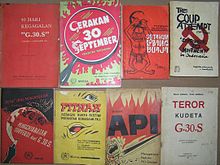

反印度尼西亞共產黨讀物 | |

| 位置 | |

| 日期 | 1965年-1966年 |

| 目標 | 印度尼西亞共產黨成員、共產主義同情者、婦女組織格瓦尼(Gerwani)成員、工會會員、爪哇族阿邦甘(Abangan)、印尼華人、無神論者、左翼分子[1][2] |

| 類型 | 政治迫害、濫殺和種族清洗[3] |

| 死亡 | 500,000[4]:3–1,200,000[4]:3[5][6][7] |

| 主謀 | 印度尼西亞軍隊和各種處決小隊,背後有美國、英國和其他西方政府的協助和鼓勵[8][9][10][11] [12][13] |

政變(即九三〇事件)失敗,印尼民眾有了釋放其壓抑許久的反共情緒的出口。他們所支持的印尼陸軍隨即也走在了清洗印度尼西亞共產黨的路上。除此之外,美國、英國、澳大利亞的情報機構在當地發動了反對印度尼西亞共產黨的黑色宣傳。冷戰期間,美國政府及其西方集團的盟友的主要目的之一是將各國納入其勢力範圍並削弱共產主義在世界各地的影響力。英國則尋求機會,想要參與了印尼 - 馬來西亞對抗,卷進與前英帝國殖民地,英聯邦成員之一,其鄰國馬來亞聯合邦戰爭的蘇加諾政府下台。

政治、經濟和軍事領域的共產主義者們被屠戮,印度尼西亞共產黨自身難保,被強行解散。屠殺始於1965年十月,叛亂發生後的數周,由首都雅加達起,擴散到中爪哇省的中東部,直至峇里省。屠戮事件在1966年年初達到高潮,之後便逐漸平息。數千位當地民兵以及陸軍參與了屠殺——無論對象是否為共產黨人。全國各地殺戮四起,印尼共在中爪哇省中東部,蘇門答臘北部的據點損失殆盡。可能有超過一百萬人在一次或數次行動中被監禁。蘇加諾在宗教、民族主義和共產主義上實施的「指導式民主」(參見蘇加諾 - 執政)被瓦解,他最重要的支持者——印尼共被軍隊以及伊斯蘭主義者清剿,而軍隊勢力此時正如日中天。1967年三月,蘇加諾被印度尼西亞臨時議會褫奪了他的總統權力,蘇哈托被任命為臨時總統。1968年三月,蘇哈托正式當選總統。

背景

編輯在印度尼西亞獨立後,蘇加諾憑藉着其「指導式民主」政策以及與其創造的團結印度尼西亞各方勢力的「納沙貢」獲得了廣泛支持。然而,隨着印度尼西亞共產黨影響力的上升和日益增強的戰鬥力,以及蘇加諾對共產主義的支持,引起了穆斯林和軍隊的嚴重擔憂,而這種擔憂隨着冷戰的加劇而加深。[14]作為世界第三大共產黨,印尼共產黨擁有約30萬名幹部和約200萬名正式黨員。[15]印尼共產黨一直試圖推廣土地改革並減少伊斯蘭教對政治的干預,並威脅到了穆斯林神職人員的社會地位。[16]蘇加諾還要求政府僱員學習他的「納沙貢」理念以及馬克思主義理論,同時會見了中華人民共和國總理周恩來,決定從中國訂購武器裝備並組建一支民兵組織,稱為第五軍,並打算親自指揮。他在一次演講中宣稱,他支持革命團體,無論他們是民族主義者、宗教主義者還是共產主義者,他說:「我是共產黨的朋友,因為共產黨是革命的人民。」[17]1964年10月,他在開羅舉行的不結盟運動峰會上表示,他目前的目標是推動整個印度尼西亞政治向左轉,從而消除軍隊中可能對革命構成危險的「反動」分子。[18]

1955年,蘇加諾在印尼萬隆主持召開了萬隆會議。大部分亞洲和非洲前殖民地國家參加了這次會議。儘管這次會議主要討論了保衛和平,爭取殖民地獨立和發展經濟等各國共同關心的問題,而不是共產黨代表大會,但這足以讓美國對蘇加諾產生懷疑,認為他有強烈的共產主義同情心甚至支持共產主義。[19]與此同時,印尼共產黨在印尼變得非常受歡迎,因此,在整個20世紀50年代的印度尼西亞選舉中,印尼共產黨的表現越來越好。它比其他政黨腐敗程度低,而且信守承諾。[19]

早在1958年,西方國家就推行鼓勵印尼軍隊對印尼共產黨和左翼採取強力行動的政策,這些政策包括旨在損害蘇加諾和印尼共產黨聲譽的秘密宣傳運動,以及向軍隊內部反共領導人提供情報以及軍事和財政支持。[20]美國中央情報局曾考慮暗殺蘇加諾,但並沒有實施。[19]

九三〇事變

編輯1965年9月30日晚上,一群被稱為「9月30日運動」的武裝分子抓獲並處決了印度尼西亞六名高級軍事將領。這些人自稱是蘇加諾的保護者,並發動先發制人的打擊,以防止「反蘇加諾」、親西方的將軍委員會可能發動政變。

在處決軍官之後,政變部隊佔領了雅加達的獨立廣場和總統府。但不久之後,蘇加諾拒絕支持該運動,因為該運動已經殺害了他的許多高級將領。隨着夜幕降臨,運動領導能力的低下開始顯現。政變部隊想要佔領電信大樓,但他們忽略了廣場的東側,也就是武裝部隊戰略預備隊的所在地。[21]蘇哈托少將控制着預備隊,在聽到政變的消息後,他迅速利用該運動的弱點,在沒有抵抗的情況下重新控制了獨立廣場。與此同時,隨着蘇加諾的衰落,印尼軍方的影響力逐漸增強,幾天之內,政府就被蘇哈托控制了。他立即派遣軍隊取締該運動,同時大肆宣揚該運動的行為對國家「構成威脅」。[21]

蘇哈托和軍方策劃的軍事宣傳運動於10月5日(武裝部隊紀念日和六名將軍的國葬日)開始席捲全國,他們將政變企圖與印尼共產黨聯繫起來。軍隊宣傳人員將被謀殺、折磨甚至閹割的將軍的生動圖片和描述傳遍印度尼西亞。儘管這些信息是偽造的,但這場宣傳活動還是取得了成功,讓許多印尼人和國際人士都相信,這起未遂政變和殘忍的謀殺是印尼共產黨試圖破壞蘇加諾總統領導下的政府。儘管印尼共產黨否認參與其中,但多年來積累的緊張和仇恨終於被釋放出來。

儘管政變只局限於雅加達且只造成12人死亡,但蘇哈托將其描述為全國性的大規模謀殺陰謀。數百萬與印尼共產黨有關的人,甚至來自偏遠村莊的文盲農民,都被描述為該運動的兇手和幫凶。在1966年初,康奈爾大學的歷史學家本尼迪克特·安德森和露絲·邁克維伊就在他們的論文中指出,蘇哈托的軍隊在九三零運動結束後,過了很久才開始進行反共大清洗。[22]從九三零運動結束到軍隊開始大規模逮捕之間,已經過去了三個星期,期間沒有發生任何暴力事件或內戰的痕跡,甚至軍隊自己也不承認。蘇加諾不斷抗議清洗,稱軍隊「為殺死老鼠而燒掉屋子」,但他無能為力,因為蘇哈托牢牢控制着武裝部隊。[22]

政治清洗

編輯在接下來的幾周里,陸軍撤換了他們認為同情印度尼西亞共產黨的文職和軍事高級領導人。[23]慢慢地,議會和內閣中蘇加諾的擁護者被清除,那些與印共有聯繫的人被剝奪了他們的職位。[24]大批的印共主要成員被捕,其中一些人被草率處決。[24]軍隊領導在雅加達組織了示威活動,印共位於雅加達總部也在10月8日被燒毀。在軍隊高層的支持下,大批的反共青年團體成立,包括軍隊支持的印度尼西亞學生行動陣線(KAMI)、印度尼西亞青年和學生行動陣線 (KAPPI) 和印度尼西亞大學校友行動陣線 (KASI)。在雅加達和西爪哇,超過10,000名印共黨員和領導人被捕,其中包括著名小說家普拉姆迪亞·阿南達·杜爾。

最初的死亡事件發生在印尼軍隊與印尼共產黨之間有組織的衝突中,其中包括一些同情共產主義並抵制蘇哈托將軍鎮壓的印尼武裝部隊和警察部隊。由於印尼共產黨大力招募新成員,海軍陸戰隊、空軍和警察機動旅的許多軍人甚至指揮官都加入過或是與印尼共產黨極其附屬組織有密切聯繫。10月初,戰略司令部和由薩爾沃·埃迪·維博沃上校領導的印尼人民武裝警察總隊准突擊隊被派往大力支持印尼共產黨的中爪哇,而忠誠度不確定的陸軍軍人則被強制退伍。與此同時,西利旺義師被部署到雅加達和西爪哇,這兩個地區與中爪哇和東爪哇不同,相對而言沒有受到大規模屠殺的影響。在中爪哇高地和茉莉芬周邊,印尼共產黨以這些地區為中心建立一個對立政權。然而,隨着蘇哈托派出的軍隊控制了局勢,人們普遍擔心美國和中國支持的派系之間會發生內戰,但這種擔憂很快就煙消雲散了。在蘇哈托部署的部隊抵達後,許多不支持蘇哈托的指揮官選擇不參戰,儘管蘇帕爾喬將軍等一些人進行了數周的抵抗。

隨着蘇加諾政權的瓦解,蘇哈托在政變後開始掌握權力。印尼共產黨的全國最高領導人被追捕和逮捕,許多領導人均被草率處決。10月初,印尼共產黨主席迪帕·努桑塔拉·艾地逃往中爪哇,但在11月22日便被支持蘇哈托的部隊逮捕並處決。曾在蘇加諾政府中擔任高級顧問的印尼共產黨領導人恩喬托於11月6日左右被槍殺,印尼共產黨第一副主席M.H.盧克曼在次年四月被殺。

外部勢力介入

編輯根據CIA於1962年的一份備忘錄,就清算蘇加諾這一問題上,美國及英國政府的意見高度一致。當時印尼反共政府與美國陸軍的聯繫相當密切——後者為前者培訓了超過1,200名軍官,「包括高級軍官」,以及相關的武器和經濟支持——但CIA否認其參與了屠戮。2017年美國國家安全檔案館與美國國家解密中心(National Declassification Center)解密的政府檔案顯示,美國對「九三〇事件」屠殺過程知情且暗中支持,並曾向印尼軍隊提供金錢、武器和印尼共產黨官員的名單,卻刻意保持沉默,誣陷北京當局。文件更指出,印尼軍方編造了中國共產黨企圖指使印尼共發動政變的謠言[25]。CIA 在1968年一份高度機密的報告中陳述,此次大屠殺「與1930年代的蘇聯大清洗運動,二戰中的納粹種族大屠殺,1950年代的中國土地改革運動,並列為20世紀最慘無人道的大屠殺」[26][27][4]:183。

被誇大的反華

編輯反華事件

編輯在一些地區,當地的印尼華人被殺害,他們的財產被搶劫和焚燒,這是反華種族主義的結果,藉口是 D. N. 艾迪特讓印尼共產黨更接近中華人民共和國。印尼華裔歷史學家伊塔·法蒂婭·納迪亞 (Ita Fatia Nadia) 在《雅加達郵報》上表示,她的父親是一名「帕圖克青年」,也是一名印尼社會黨黨員。1965年10月,她七歲時,印尼陸軍士兵來到她位於日惹的家進行檢查,隨後他便失蹤了.她還記得,在上學的路上看到屍體,意識到失蹤的家人和鄰居都被殺了,後來她母親告訴她不要管這件事[28]。

20 世紀50年代和60年代初,峇里島上也出現了傳統種姓制度支持者與反對傳統價值觀者(尤其是印尼共產黨)之間的衝突。印尼共產黨被公開指責致力於摧毀該島的文化、宗教和性格,而峇里人和爪哇人一樣,也被敦促摧毀印尼共產黨。峇里島辛加拉惹和登巴薩鎮的所有華人店鋪均被摧毀,許多涉嫌為「蓋世太保」提供經濟支持的店鋪業主被殺害。1965年12月至1966年初,估計有8萬峇里族人被殺,約佔當時該島人口的5%,所佔比例高於印度尼西亞其他任何地方[29]。

在西加里曼丹,1967年屠殺結束後,當地的達雅克人將45,000名華人從農村地區驅逐出去,造成2,000至5,000人死亡。華人拒絕反擊,因為他們認為自己是「別人土地上的客人」,目的只是進行貿易[30][31] 。

以反華之名掩蓋反共

編輯加拿大不列顛哥倫比亞大學歷史系副教授約翰・魯薩(John Roosa)向德國之聲解釋,當年的反共大屠殺是針對印尼共產黨而來,並非華人,過去曾有論述將該事件塑造成「反華種族清洗」或「屠華事件」,都是不對的。

對印尼華人的歧視在蘇門答臘和加里曼丹]的屠殺中扮演了重要角色,這些屠殺被稱為種族滅絕。Charles A. Coppel 對這種說法提出了嚴厲批評,他認為西方媒體和學者不願面對他們所支持的反共議程的後果[32] ,而是把印尼種族主義當成替罪羊,並誇大其詞地聲稱有數十萬或數百萬印尼華人被殺[33] 。Charles A. Coppel 在一篇題為「從未發生過的種族滅絕:解釋1965-1966年印尼反華大屠殺的神話」的文章中談到了這種歪曲的報道。Coppel在1998年5月騷亂的報道中也看到了同樣的偏見,當時人道主義志願者團隊指出,非華裔搶劫者占被殺人數的大多數[34] 。他的論點繼續引發爭論[35]。

據估計,約有2,000名印尼華人被殺害(反共大屠殺總死亡人數估計在50萬至300萬人之間),有記錄顯示,在望加錫、棉蘭和龍目島發生了屠殺[36]。Robert Cribb和Charles A. Coppel指出,在清洗期間,實際上只有「相對較少」的華人被殺害,而大多數死者都是印尼原住民[37] 。華人的死亡人數達數千人,而印尼原住民的死亡人數則達數十萬。被屠殺的絕大多數人是峇里人和爪哇人[33]。

新加坡南洋理工大學歷史系助理教授周陶沫(Taomo Zhou)向德國之聲指出,「九三〇事件」對中共而言,雖然是外交上很大的挫敗,但卻被中共拿來政治動員文化大革命。當時中華人民共和國許多報刊稱印尼反共大屠殺是蘇哈托迫害印尼共、華人、華僑的行為,所以「國內群眾要繼續革命到底」,強烈譴責蘇哈托是「法西斯走狗」。[25]。

後續

編輯由於蘇哈托政權下的鎮壓,大屠殺並沒有被列入印尼的教科書中,也沒有對此事做出反省。就意識形態而言,如何為大屠殺事件中所展現的民眾暴力做出一個完美的解釋,是所有學者所面臨的挑戰。為避免再次發生類似九三〇事件的動盪,「新秩序」政權採取保守主義,對已有的政治體系做出了嚴格的控制。在蘇哈托一派看來,由於共產主義本身及其所帶來的威脅,污名化(參見社會污名)以削減其影響力的手段是必不可少的。這種情況一直持續到了21世紀的今天。

參見

編輯參考文獻

編輯- ^ Ricklefs (1991), p. 288.

- ^ Mechanics of Mass Murder: A Case for Understanding the Indonesian Killings as Genocide. Journal of Genocide Research. [2017-12-22]. (原始內容存檔於2022-04-16).

- ^ Melvin, Jess. Mechanics of Mass Murder: A Case for Understanding the Indonesian Killings as Genocide. Journal of Genocide Research. 2017, 19 (4): 487–511. doi:10.1080/14623528.2017.1393942 .

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Robinson, Geoffrey B. The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965–66. Princeton University Press. 2018 [2021-11-30]. ISBN 978-1-4008-8886-3. (原始內容存檔於2018-08-20).

- ^ Melvin, Jess. The Army and the Indonesian Genocide: Mechanics of Mass Murder. Routledge. 2018: 1 [2021-11-30]. ISBN 978-1-138-57469-4. (原始內容存檔於2019-06-08).

- ^ Blumenthal, David A.; McCormack, Timothy L. H. The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence Or Institutionalised Vengeance?. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 2008: 80 [2024-02-22]. ISBN 978-90-04-15691-3. (原始內容存檔於2024-01-05) (英語).

- ^ The Memory of Savage Anticommunist Killings Still Haunts Indonesia, 50 Years On (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館), Time

- ^ Robinson, Geoffrey B. The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965–66. Princeton University Press. 2018: 206–207 [2021-11-30]. ISBN 978-1-4008-8886-3. (原始內容存檔於2018-08-20).

In short, Western states were not innocent bystanders to unfolding domestic political events following the alleged coup, as so often claimed. On the contrary, starting almost immediately after October 1, the United States, the United Kingdom, and several of their allies set in motion a coordinated campaign to assist the Army in the political and physical destruction of the PKI and its affiliates, the removal of Sukarno and his closest associates from political power, their replacement by an Army elite led by Suharto, and the engineering of a seismic shift in Indonesia's foreign policy towards the West. They did this through backdoor political reassurances to Army leaders, a policy of official silence in the face of the mounting violence, a sophisticated international propaganda offensive, and the covert provision of material assistance to the Army and its allies. In all these ways, they helped to ensure that the campaign against the Left would continue unabated and its victims would ultimately number in the hundreds of thousands.

- ^ Melvin, Jess. Telegrams confirm scale of US complicity in 1965 genocide. Indonesia at Melbourne. University of Melbourne. 20 October 2017 [21 October 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-08).

The new telegrams confirm the US actively encouraged and facilitated genocide in Indonesia to pursue its own political interests in the region, while propagating an explanation of the killings it knew to be untrue.

- ^ Simpson, Bradley. Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.–Indonesian Relations, 1960–1968. Stanford University Press. 2010: 193 [2024-02-22]. ISBN 978-0-8047-7182-5. (原始內容存檔於2018-06-25).

Washington did everything in its power to encourage and facilitate the Army-led massacre of alleged PKI members, and U.S. officials worried only that the killing of the party's unarmed supporters might not go far enough, permitting Sukarno to return to power and frustrate the [Johnson] Administration's emerging plans for a post-Sukarno Indonesia. This was efficacious terror, an essential building block of the neoliberal policies that the West would attempt to impose on Indonesia after Sukarno's ouster.

- ^ Perry, Juliet. Tribunal finds Indonesia guilty of 1965 genocide; US, UK complicit. CNN. 21 July 2016 [5 June 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2018-06-13).

- ^ Bevins, Vincent. The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World. PublicAffairs. 2020: 157. ISBN 978-1541742406.

The United States was part and parcel of the operation at every stage, starting well before the killing started, until the last body dropped and the last political prisoner emerged from jail, decades later, tortured, scarred, and bewildered.

- ^ Lashmar, Paul; Gilby, Nicholas; Oliver, James. Revealed: how UK spies incited mass murder of Indonesia's communists. The Observer. 17 October 2021 [2024-02-22]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-22).

- ^ Michaels, Samantha. It’s Been 50 Years Since the Biggest US-Backed Genocide You’ve Never Heard Of. Mother Jones. [2024-09-30] (美國英語).

- ^ Wertheim, W.F. Indonesia - The Indonesian Killings 1965–1966: Studies from Java and Bali. Edited by Robert Cribb. Clayton, Vic: Monash University, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash Papers on Southeast Asia, No. 21, 1990. Pp. 279. Illustrations, Maps, Glossary, Notes, Index.. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 1993-03, 24 (1). ISSN 0022-4634. doi:10.1017/s0022463400001661.

- ^ Adam Schwarz. A nation in waiting. Internet Archive. Allen & Unwin. 1994. ISBN 978-1-86373-635-0.

- ^ Subritzky, John. The Deepening Crisis, August-December 1964. Confronting Sukarno. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. 2000: 115–136. ISBN 978-1-349-41986-9.

- ^ Andrew, John Rotter. Light at the end of the tunnel. Rowman & Littlefield Publ. 2010: 273. ISBN 978-0-7425-6133-5.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Bevins, Vincent. The Jakarta method: Washington's anticommunist crusade & the mass murder program that shaped our world First Trade Paperback Edition. New York, NY: PublicAffairs. 2021. ISBN 978-1-5417-4240-6.

- ^ The Killing Season | Princeton University Press. press.princeton.edu. 2018-02-13 [2024-09-30] (英語).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Törnquist, Olle. ROOSA, JOHN. Pretext for Mass Murder. The September 30th Movement and Suharto's Coup d'État in Indonesia. [New Perspectives in Southeast Asian Studies.] University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 2006. xii, 329 pp. Ill. $60.00 (Paper: $23.95.). International Review of Social History. 2007-07-09, 52 (02). ISSN 0020-8590. doi:10.1017/s0020859007072963.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Roosa, John. Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto's Coup D'Etat in Indonesia. Univ of Wisconsin Press. 2006-08-03. ISBN 978-0-299-22030-3 (英語).

- ^ Adam Schwarz. A nation in waiting. Internet Archive. Allen & Unwin. 1994. ISBN 978-1-86373-635-0.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 Vickers, Adrian. A history of modern Indonesia. Internet Archive. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York : Cambridge University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-521-83493-3.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 德國之聲. 印尼:共产党与“930事件”为何仍是禁忌话题?. 德國之聲. [2024-02-15]. (原始內容存檔於2024-02-15).

- ^ Mark Aarons (2007). "Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)." In David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (eds). The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law). 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期5 January 2016. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-04-15691-7 p. 81 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ David F. Schmitz. The United States and Right-Wing Dictatorships, 1965–1989. Cambridge University Press. 2006: 48–9. ISBN 978-0-521-67853-7.

- ^ 1965 survivors seek closure as UK documents expose Western complicity in mass killings. The Jakarta Post. [2023-06-28] (英語).

- ^ Friend (2003), p. 111; Taylor (2003), p. 358; Vickers (2005), p. 159; Robinson (1995), p. ch. 11.

- ^ John Braithwaite. Anomie and violence: non-truth and reconciliation in Indonesian peacebuilding. ANU E Press. 2010: 294 [15 December 2011]. ISBN 978-1-921666-22-3.

In 1967, Dayaks had expelled Chinese from the interior of West Kalimantan. In this Chinese ethnic cleansing, Dayaks were co-opted by the military who wanted to remove those Chinese from the interior who they believed were supporting communists. The most certain way to accomplish this was to drive all Chinese out of the interior of West Kalimantan. Perhaps 2000–5000 people were massacred (Davidson 2002:158) and probably a greater number died from the conditions in overcrowded refugee camps, including 1500 Chinese children aged between one and eight who died of starvation in Pontianak camps (p. 173). The Chinese retreated permanently to the major towns...the Chinese in West Kalimantan rarely resisted (though they had in nineteenth-century conflict with the Dutch, and in 1914). Instead, they fled. One old Chinese man who fled to Pontianak in 1967 said that the Chinese did not even consider or discuss striking back at Dayaks as an option. This was because they were imbued with a philosophy of being a guest on other people's land to become a great trading diaspora.

- ^ Eva-Lotta E. Hedman. Eva-Lotta E. Hedman , 編. Conflict, violence, and displacement in indonesia. SOSEA-45 Series illustrated. SEAP Publications. 2008: 63 [15 December 2011]. ISBN 978-0-87727-745-3.

the role of indigenous Dayak leaders accounted for their "success." Regional officers and interested Dayak leaders helped to translate the virulent anti-community environment locally into an evident anti-Chinese sentiment. In the process, the rural Chinese were constructed as godless communists complicit with members of the local Indonesian Communist Party...In October 1967, the military, with the help of the former Dayak Governor Oevaang Oeray and his Lasykar Pangsuma (Pangsuma Militia) instigated and facilitated a Dayak-led slaughter of ethnic Chinese. Over the next three months, thousands were killed and roughly 75,000 more fled Sambas and northern Pontianak districts to coastal urban centers like Pontianak City and Singkawang to be sheltered in refugee and "detainment" camps. By expelling the "community" Chinese, Oeray and his gang... intended to ingratiate themselves with Suharto's new regime.

- ^ Coppel 2008, p. 122.

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Coppel 2008, p. 118.

- ^ Coppel 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Melvin, Jess (2013), Not Genocide? Anti-Chinese Violence in Aceh, 1965–1966 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期8 June 2015., in: Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 32, 3, 63–91. ISSN 1868-4882 (online), ISSN 1868-1034 (print)

- ^ Tan 2008,第240–242頁.

- ^ Cribb & Coppel 2009.

外部連結

編輯- The Indonesia/East Timor Documentation Project (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). National Security Archive

- Lessons of the 1965 Indonesian Coup Terri Cavanagh, World Socialist Web Site, 1998.

- U.S. Seeks to Keep Lid on Far East Purge Role(頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). The Los Angeles Times. 28 July 2001.

- Accomplices in Atrocity.(頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) The Indonesian killings of 1965(頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 7 September 2008

- The Forgotten Massacres (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). Jacobin. 2 June 2015.

- The Indonesian Massacre: What Did the US Know? (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). The New York Review of Books. November 2, 1015.

- 50 years ago today, American diplomats endorsed mass killings in Indonesia.(頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) Here’s what that means for today.(頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) The Washington Post. December 2, 2015.