多囊卵巢综合症

多囊性卵巢综合症(英语:Polycystic ovary syndrome,简称PCOS),又称斯-李二氏症(Stein-Leventhal syndrome),是女性因为雄性激素上升所导致的症状[4]。多囊性卵巢的症状包含月经不规律或是无月经、月经量过多、多毛症、粉刺、盆腔疼痛、难以受孕与黑棘皮症[3]。相关的病症包含第二型糖尿病、肥胖症、阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停、心血管疾病、情感障碍与子宫内膜癌[4]。

| 多囊卵巢症候群 | |

|---|---|

| 又称 | 高雄性激素无排卵(Hyperandrogenic anovulation,HA)[1]、斯-李二氏症(Stein–Leventhal syndrome)[2] |

| |

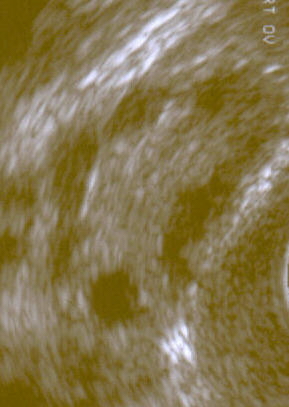

| 超声波扫描下的多囊卵巢综合症。 | |

| 症状 | 月经失调、经血过多、多毛症、痤疮、骨盆痛、不孕、黑棘皮症[3] |

| 并发症 | 2型糖尿病、肥胖症、阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停、心血管疾病、情感障碍、子宫内膜癌[4] |

| 病程 | 长期[5] |

| 类型 | 症候群、荷尔蒙失调、遗传性疾病、生殖系统疾病、ovarian dysfunction[*]、疾病 |

| 病因 | 遗传或环境因素[6][7] |

| 风险因素 | 肥胖症、运动不足、家族病史[8] |

| 诊断方法 | 无排卵、高雄激素、卵巢囊肿[4] |

| 鉴别诊断 | 肾上腺增生症、甲状腺机能低下症、高泌乳素血症[9] |

| 治疗 | 减肥、运动[10][11] |

| 药物 | 避孕药、二甲双胍、抗雄激素[12] |

| 患病率 | 适产年龄 2% 至 20% 的女性[8][13] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 妇科学 |

| ICD-11 | 5A80.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 256.4 |

| OMIM | 184700 |

| MedlinePlus | 000369 |

| eMedicine | 256806、404754 |

| Orphanet | 3185 |

多囊性卵巢会受基因遗传与环境因素影响[6][7]。其危险因子包含肥胖症、运动量不足或是有家族病史[8]。如果有以下三种症状中的两种便可诊断患者有多囊性卵巢:无排卵、雄性激素过高与卵巢囊肿[4]。囊肿可以由超声波影像检测。其他造成类似症状的疾病包含先天性肾上腺增生症,甲状腺机能低下症与高泌乳素血症[9]。

多囊性卵巢综合症目前并无特效药可以治疗[5]。现行治疗方式包括减重和运动等生活型态调整[11][10],避孕药物对于调整经期、抑制多余的毛发生长与改善青春痘有所帮助。二甲双胍和抗雄性激素可能能够改善多囊性卵巢综合症,且针对青春痘和多毛等症状有一定治疗效果[12]。减重或是使用可洛米分、降血糖药物每福敏则有助于改善不孕的状况。若以上治疗对于病人都没有效果且病人有生育考量,则可考虑体外人工授精这个选项[14]。

多囊性卵巢综合症是18岁到44岁女性间最常见的内分泌疾病[15]。一般认为,多囊卵巢综合症的发生率在女性生育年龄期间占约20%(根据鹿特丹诊断指引,英国为26%、澳洲为17.8%、土耳其为19.9%、伊朗为15.2%[16]。)多囊卵巢综合症是现今导致不孕的主要原因之一[4]。目前已知最早的多囊卵巢综合症病例于1721年纪录于意大利[17]。

体征及症状

编辑常见的体征和症状如下:

- 月经失调: 多囊卵巢综合症主要导致月经次数过少(一年月经次数少于九次)或闭经(没有月经连续三到数个月以上),也可能造成其他类型的月经失调[15][18]。

- 不孕[18]: 这是一个由慢性无排卵导致的常见症状 (缺乏排卵)[15]。

- 雄性激素分泌过多: 即为雄性素过多症。最常见的症状为痤疮和多毛症,也可能导致月经过多 (周期长且量多的月经周期), 雄激素过多型脱发症 (增加毛发脱落程度及弥漫性脱发), 或其他症状[15][19]。 约有四分之三的多囊卵巢综合症女性患者 (根据 NIH/NICHD 1990的诊断标准))有出现高雄性素血症的症状[20]。

- 代谢症候群:[18]有肚腩赘肉且出现与胰岛素抗性有关的症状[15]。 罹患多囊卵巢综合症的女性的血清中胰岛素与升半胱胺酸浓度较正常女性来的高且有胰岛素抗性[21]。

原因

编辑多囊卵巢综合症为一种成因不明的异质性失调。[18][22][23] 有一些证据如: 家族病例、同卵双胞胎相比异卵双胞胎在多囊卵巢综合症的内分泌和代谢之遗传性特征上有较高的一致性等,点出多囊性卵巢综合症可能为遗传性疾病[7][22][23]。亦有证据表明若胎儿于子宫中暴露于高浓度的雄性激素与抗穆氏管荷尔蒙中,随着年纪增长会提升其患多囊卵巢综合症的风险。[24]

基因

编辑致病性的基因为体染色体显性遗传,在女性身上具有高度的基因外显性且多变的表现度;这代表小孩有50%的几率从双亲其中一方获得可能致病的基因片段,如果获得此基因片段的为女儿,则会出现一定程度上的病征[23][25][26][27]。 异变基因可能从父母双方遗传而来,也可能遗传给儿女(可能成为带原者或是早期脱发或毛发过多症状者) [25][27]。

表现型:有一部分患者个疾病表现为卵泡膜分泌过多的雄性素 [26]。确切的基因影响方式尚未被确认[7][23][28]。在少数的案例,单个基因的突变有可能造成综合性的突变症状[29]。目前对该综合症的发病病理机致的研究指出,多囊卵巢综合症为复杂的多基因疾病[30]。

多囊卵巢综合症症状的严重程度似乎主要取决于肥胖症[7][15][31]。

多囊卵巢综合症可视为一种代谢疾病,其的部分症状为“可逆的”。 即便多囊卵巢综合症由28个症状组成,但其仍被视为一种妇科疾病。

即使多囊卵巢综合症的病名表明卵巢为该疾病的病理核心,但是囊肿为一种症况而非病因。就算两个卵巢被摘除,部分多囊卵巢综合症的症状仍会持续下去,其症状在不存在囊种的状况下仍有可能出现。自从1935年Stein和Leventhal首次描述以来,诊断、症状和致病因素的标准仍为争议的主题之一。因为卵巢为首要受影响的器官,妇科学者们通常视其为一种妇科疾病。然而,近年来许多观察显示多囊性卵巢为一种多重系统性失调疾病,主要问题源自于下丘脑贺尔蒙调节失调 ,许多器官也与此调节有关。多囊性卵巢这个名称源自于超声波诊断之影像。多囊性卵巢综合症的症状非常多变,且只有约百分之15的患者可由超声波影像看出其卵巢中有囊肿。[32]

环境

编辑多囊卵巢综合症可能与产前经期、表观遗传学因子、环境影响(尤其是工业中产生的内分泌干扰素[33]如双酚A与特定药物)及肥胖比例增加有关,上述任何原因之一都有可能是使病症恶化的缘由。[33][34][35][36][37][38][39]

发病机制

编辑多囊性卵巢的发展会刺激卵巢持续制造分泌过量的雄性激素,尤其是睾固酮,通常会伴随着以下的其中一个症状或是两者皆有(几乎肯定其具有遗传易受性[26]):

多囊性卵巢综合症因其在超声波诊断中普遍可见的大量卵巢囊肿闻名。这些“囊肿”其实是未成熟的滤泡而非囊肿。这些滤泡由初级滤泡发育而成, 但在空腔滤泡期早期因为卵巢功能停止发育,这些滤泡会出现在卵巢周边,在超声波检验的影像中看起来像成串的珍珠[来源请求]。

患有多囊性卵巢症候群的妇女因为下丘脑释放促性腺激素释放激素的频率增加,导致黄体成长激素与滤泡刺激素的比值升高[40]。

大多数具有PCOS的妇女具有胰岛素抵抗或肥胖的症状。 他们的胰岛素浓度异常的提高导致“下丘脑-垂体-卵巢轴”区域中的异常并引起PCOS的症状。高胰岛素血症提高GnRH的释放频率、黄体成长激素量多过滤泡刺激素,因而占了主导地位、增加卵巢雄激素的产生、减少滤泡的成熟并减少SHBG的作用[18]。此外,过多的胰岛素会透过PI3K调高17α羟化酶的活性,而17α羟化酶的活性也和雄激素前体的合成有关[41],因此过多胰岛素的几个效果都会提高PCOS的风险[42]。胰岛素抵抗是女性常见的情形,在正常体重的女性及体重过重的女性都可能会出现[10][15][21]。

诊断

编辑并不是每一个多囊卵巢综合症的病人都有出现多囊卵巢的症状,也并非所有卵巢曩肿的病患都有多囊卵巢综合症的症状;虽然骨盆超声波是主要的诊断工具,但也并不是唯一个诊断工具[43]。虽然该综合征与广泛的症状相关,最直接的诊断方法是使用鹿特丹诊断标准。

2023 年 8 月,Human Reproduction[44]、Fertility and Sterility[45]、The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism[46] 和 European Journal of Endocrinology[47] 同步发表的《2023 年国际基于循证医学证据多囊卵巢综合征指南》 是目前的诊断指南。

-

多囊卵巢在超声波检查上显示的图样

-

多囊卵巢在阴道超声波检查上显示的图样

-

多囊卵巢在超声波检查上显示的图样

定义

编辑以下是两种常见的定义:

美国国立卫生研究院诊断标准

编辑- 在1990年,由国立卫生研究院 (美国)/ 美国国家儿童健康与人类发展中心赞助的协商研讨会提出,如果一个人具有以下所有症状,表示该人罹患多囊卵巢综合症[48]:

鹿特丹诊断标准(Rotterdam diagnostic criteria)

编辑鹿特丹诊断标准涵盖更广泛的有症状妇女,最显著的部分是在于并未有雄性素过剩的妇女也被列入在其中。 评论家认为,从研究雄激素过多的妇女获得的结果不一定可以推广到给没有雄激素过剩的妇女身上[51][52]。

- Androgen Excess PCOS Society

- 2006年,Androgen Excess PCOS Society提出了一套严谨诊断标准[15]:

- 具有雄性激素过剩症状

- 出现排卵不规则、无排卵或多囊卵巢症状,亦或同时出现上述症状

- 排除会引起过量雄激素活性的其他因素*

鉴别诊断

编辑应该调查其他原因,例如甲状腺机能低下症、先天性肾上腺增生症(21-羟化酶缺乏症)、库兴氏症候群、高乳促素血症、雄激素分泌性肿瘤以及其他垂体或肾上腺疾病。[15][50]<[53]

处置

编辑多囊卵巢综合症的主要治疗方法包括:调整生活方式及药物治疗[54]。

主要治疗目标大致可分为下列四点:

目前现行疗法中何为最佳治疗方式仍是相当大的争议,其中一个主要原因是因为缺乏比较不同疗程疗效的大规模临床试验。样本往往是不太可靠因此可能产生矛盾不可靠的结果。

有助于减轻体重或降低胰岛素抗性的一般干预措施对于改善多囊卵巢综合症的症状有益,体重增加与胰岛素抗性被视为是潜在的病因。由于多囊卵巢综合症有可能会引起严重的情绪障碍,因此适当的精神支持对于病情可能是有益的。[55]

饮食

编辑当多囊卵巢综合症与超重或肥胖有关时,减肥是恢复规律月经的最有效方法,但是很多女性很难达到并维持显著的体重减轻。2013年的科学评估发现,减肥,与饮食组成无关,可改善重量和体重组成、怀孕率、月经规律、排卵、雄激素过高、胰岛素抗性、脂质以及生活质量。[56]即使如此,从水果、蔬菜和全谷物中获得大部分碳水化合物的低GI饮食,相对于营养素均衡的健康饮食,仍能更好的改善月经规律。[56]

维生素D缺乏症可能在代谢症候群的发展中发挥一定的作用,故遵照医嘱补充缺乏的营养素是极为重要的[57][58]。然而,2015年的系统评估并没有发现维生素D具有减轻多囊卵巢综合症中代谢和激素失调情况的证据。[59]截至2012年,使用营养补充品预防多囊卵巢综合症患者代谢缺陷的干预措施已经在小型、不受控制的和非随机的临床试验中进行了测试;而所得数据不足以推荐使用。[60]

药物

编辑用于治疗多囊卵巢综合症的药物有避孕药及二甲双胍。口服避孕药能增加体内性激素结合球蛋白生产,促进游离睾酮的结合。这减少了由高睾丸激素引起的多毛症状,并调节恢复正常月经周期。二甲双胍是在2型糖尿病中常用的一种降低胰岛素排斥的药物,并在英国,美国,澳大利亚和欧盟标示外使用用来治疗多囊卵巢综合症中的胰岛素排斥。在许多情况下,二甲双胍也能协助卵巢功能并恢复正常排卵[18][57][61]。螺内酯可用于其抗雄激素作用,而二氟甲基鸟氨酸则可用于减少面部毛发。较新的胰岛素抵抗药物噻唑烷二酮(格列酮)显示出与二甲双胍相当的功效,但二甲双胍具有更轻微的副作用[62][63]。 英国国家健康与照顾卓越研究院在2004年提出建议,当其他治疗未能产生效果时,将给予给予BMI高于25的病患服用二甲双胍[64][65]。二甲双胍在每种类型的多囊卵巢综合症中可能并非有效的,因此对于是否应该用作一般一线治疗存在一些分歧[66]。羟甲基戊二酸单酰辅酶A还原酶抑制剂在治疗潜在代谢综合征方面的应用尚不清楚[67]。

多囊卵巢综合症可能导致难以受孕,因为它会导致不规律排卵。试图怀孕时,会使用诱导生育的药物包括排卵诱导剂克罗米酚或 脉冲亮丙瑞林 。 二甲双胍与克罗米酚组合使用时,可提高生殖治疗的疗效。[68]二甲双胍被认为在怀孕期间使用是安全的,于美国的怀孕分级为B[69]。2014年的评论得出结论,在三个月内使用二甲双胍治疗的女性并不会增加产下先天性障碍婴儿的风险[70]。

不孕症

编辑多毛症及痤疮

编辑月经不规律

编辑如果病患目前没有怀孕需求,可以借由服用复合口服避孕药来调节月经紊乱[18][57]。 调理生理周期的主要目的是让女性生活上比较方便,改善女性对于生理周期与自己的感受;若能自然规律行经,便不需借由服药使生理周期变得规律。

如果不期望定期的月经周期,则不一定需要不规则循环的治疗。大多数专家说,如果至少每三个月发生一次月经,那么子宫内膜就会经常流下来,以防止增加子宫内膜异常或癌症的风险。[71] 如果月经频率极低或根本没来,推荐使用某些形式的助孕素。[72] 其中一种替代方案即是定期服用一次口服助孕素(例如,每三个月)以诱发可预测的月经出血。[18]

替代药物

编辑一篇2017年发表的科学论文指出肌醇与D-手性肌醇可能具有调节生理周期与改善排卵的功效,然而目前仍然缺乏其是否能影响怀孕几率的证据,一篇于2011年发表的综述文章亦指出目前缺乏足够的证据去证明D-手性肌醇具有任何功效。 [73][74] [75] 两篇分别发表于2012年与2017年的综述文章点出补充肌醇似乎能够有效改善多囊性卵巢综合症的几种激素紊乱,且能降低采取体外受精之女性的促性腺激素释放激素浓度与改善其卵巢过度刺激症的发作时间。[76][77] [78] 对于针灸是否能改善多囊性卵巢综合症方面,目前仍然缺乏足够的科学证据来证实其效用。[79][80]

预测

编辑多囊性卵巢综合症的高风险伴随症状:

- 可能发生子宫内膜增生症和子宫内膜癌,因为子宫内膜过度积累,且也缺乏黄体素导致雌激素对子宫细胞的刺激延迟[18][48][81]。这种风险是否直接归因于综合征或相关的肥胖(高胰岛素血症和雄激素过多症)还不清楚。[82][83][84]

- 胰岛素抗性或第二型糖尿病[18]:2010年发表的一项论文得出,即使在控制身高体重指数(BMI)时,多囊性卵巢综合症患者的胰岛素抗性和II型糖尿病患病率也会升高。[48][85]多囊性卵巢综合症也使一个女人,容易患有妊娠糖尿病,特别是肥胖症患者[18]。

- 高血压,特别是肥胖或怀孕期间[18]。

- 忧郁和焦虑[15][86]

- 血脂异常[18] (脂质代谢障碍 ) 胆固醇和甘油三酯。具有多囊卵巢综合症的妇女显示动脉粥样硬化去除机制会减弱,导致残余物,似乎与胰岛素抗性或II型糖尿病无关。[87]

- 心血管疾病[18][48]研究分析估计有多囊性卵巢综合症患者的动脉疾病风险相对于没有女性的2倍,与BMI无关[88]。

- 中风[48][48]

- 体重增加[18]

- 流产[89][90]

- 睡眠呼吸中止症,特别是肥胖症患者[18]

- 非酒精性脂肪肝,特别是肥胖症患者[18]

- 黑棘皮症(腋下,鼠蹊部与后颈出现暗色皮肤斑纹)[48]

- 自体免疫甲状腺炎[91]

早期诊断和治疗可能会降低其中一些风险,如II型糖尿病和心脏病。

卵巢癌和乳腺癌的风险总体上没有显著增加。[81]

流行病学

编辑多囊性卵巢综合症的盛行率受到诊断标准的影响。 世界卫生组织在2010年时估计全世界约有一亿一千六百万名女性(约3.4%的女性)受多囊性卵巢综合症影响。[92]一份以鹿特丹诊断诊断指引为准的多囊性卵巢综合症流行率社区研究发现,大约有百分之18的女性患有多囊性卵巢,而这些患者约有百分之70先前并未被确诊出患有多囊性卵巢综合症。[15]

约有百分之8到25的一般女性在超声波诊断中会看到有多囊性卵巢。[93][94][95][96]服用口服避孕药的女性中,有14%发现有多囊性卵巢[94]。卵巢囊肿也是使用释放黄体素的子宫环后常见的副作用。[97]

历史

编辑这种症状最早在1935年由美国妇科医生Irving F. Stein, Sr.与Michael L. Leventhal首次描述,其原始名称为斯-李二氏症[43][48] 。

目前已知最早的多囊卵巢综合症记录,是1721年间源自意大利的记录[17]。关于卵巢囊肿的相关变化描述最早出现在1844年[17]。

社会及文化

编辑经费

编辑2005年在美国有约四百万起多囊卵巢综合症的病例,其医疗费用有43.6亿美元[98]。2016年国立卫生研究院的研究预算有323亿美元,其中有0.1%用在多囊卵巢综合症的研究上[99]。

名称

编辑这种综合征的其他名称包括多囊卵巢疾病、功能性卵巢雄激素过多症、卵巢滤泡膜细胞增殖、硬皮囊性卵巢综合征和斯-李二氏症。斯-李二氏症为其原始名称,现在使用这个名称都仅限于具有不孕症、多毛症、卵巢有多发囊状肿大的闭经女性[43]。

这种疾病的名称“多囊卵巢综合症”是因为在医学影像中可见多囊性卵巢而得此称[18]。多囊性卵巢在靠近卵巢表面处有极大量正在发育的卵子,其在超声波中可用肉眼鉴别[43],看起来像许多小囊肿[100]。

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ Kollmann M, Martins WP, Raine-Fenning N. Terms and thresholds for the ultrasound evaluation of the ovaries in women with hyperandrogenic anovulation. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014, 20 (3): 463–4. PMID 24516084. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu005.

- ^ USMLE-Rx. MedIQ Learning, LLC. 2014.

Stein-Leventhal syndrome, also known as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), is a disorder characterized by hirsutism, obesity, and amenorrhea because of luteinizing hormone-resistant cystic ovaries.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 What are the symptoms of PCOS? (05/23/2013). www.nichd.nih.gov. [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-03).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Condition Information. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. 2013-05-23 [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-04).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 http://www.nichd.nih.gov. Is there a cure for PCOS?. 2013-05-23 [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-05). 外部链接存在于

|title=(帮助) - ^ 6.0 6.1 De Leo V, Musacchio MC, Cappelli V, Massaro MG, Morgante G, Petraglia F. Genetic, hormonal and metabolic aspects of PCOS: an update. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E (Review). 2016, 14 (1): 38. PMC 4947298 . PMID 27423183. doi:10.1186/s12958-016-0173-x.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kandarakis H, Legro RS. The role of genes and environment in the etiology of PCOS. Endocrine. 2006, 30 (1): 19–26. PMID 17185788. doi:10.1385/ENDO:30:1:19.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 How many people are affected or at risk for PCOS?. http://www.nichd.nih.gov. 2013-05-23 [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-04). 外部链接存在于

|website=(帮助) - ^ 9.0 9.1 How do health care providers diagnose PCOS?. http://www.nichd.nih.gov/. 2013-05-23 [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-02).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Mortada R, Williams T. Metabolic Syndrome: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. FP Essentials (Review). 2015, 435: 30–42. PMID 26280343.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Giallauria F, Palomba S, Vigorito C, Tafuri MG, Colao A, Lombardi G, Orio F. Androgens in polycystic ovary syndrome: the role of exercise and diet. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine (Review). 2009, 27 (4): 306–15. PMID 19530064. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1225258.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Treatments to Relieve Symptoms of PCOS. http://www.nichd.nih.gov/. 2014-07-14 [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-02).

- ^ editor, Lubna Pal,. Diagnostic Criteria and Epidemiology of PCOS. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Current and Emerging Concepts.. Dordrecht: Springer. 2013: 7 [2017-10-28]. ISBN 9781461483946. (原始内容存档于2020-02-01).

- ^ Treatments for Infertility Resulting from PCOS. http://www.nichd.nih.gov/. 2014-07-14 [13 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-02).

- ^ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 2010, 8 (1): 41. PMC 2909929 . PMID 20591140. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-41.

- ^ Diagnostic Criteria and Epidemiology of PCOS; Heather R. Burks and Robert A. Wild; Book Title: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome; Subtitle: Current and Emerging Concepts; Part I; Pages: pp 03-10; Copyright: 2014; DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8394-6_17; Print ISBN 978-1-4614-8393-9; Online ISBN 978-1-4614-8394-6; Publisher: Springer New York. (http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4614-8394-6_17 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kovacs, Gabor T.; Norman, Robert. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cambridge University Press. 2007-02-22: 4 [29 March 2013]. ISBN 9781139462037. (原始内容存档于2016-04-19).

- ^ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 18.14 18.15 18.16 18.17 18.18 Mayo Clinic Staff. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – All. MayoClinic.com. Mayo Clinic. 4 April 2011 [15 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-30).

- ^ Christine Cortet-Rudelli; Didier Dewailly. Diagnosis of Hyperandrogenism in Female Adolescents. Hyperandrogenism in Adolescent Girls. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Sep 21, 2006 [2006-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2007-09-30).

- ^ Huang A, Brennan K, Azziz R. Prevalence of hyperandrogenemia in the polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosed by the National Institutes of Health 1990 criteria. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93 (6): 1938–41. PMC 2859983 . PMID 19249030. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.138.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Nafiye Y, Sevtap K, Muammer D, Emre O, Senol K, Leyla M. The effect of serum and intrafollicular insulin resistance parameters and homocysteine levels of nonobese, nonhyperandrogenemic polycystic ovary syndrome patients on in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93 (6): 1864–9. PMID 19171332. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.024.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Page 836 (Section:Polycystic ovary syndrome) in: Fauser BC, Diedrich K, Bouchard P, Domínguez F, Matzuk M, Franks S, Hamamah S, Simón C, Devroey P, Ezcurra D, Howles CM. Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2011, 17 (6): 829–47. PMC 3191938 . PMID 21896560. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Legro RS, Strauss JF. Molecular progress in infertility: polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 78 (3): 569–76. PMID 12215335. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03275-2.

- ^ Filippou, P; Homburg, R. Is foetal hyperexposure to androgens a cause of PCOS?. Human Reproduction Update. 1 July 2017, 23 (4): 421–432. PMID 28531286. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmx013.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Crosignani PG, Nicolosi AE. Polycystic ovarian disease: heritability and heterogeneity. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2001, 7 (1): 3–7. PMID 11212071. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.1.3.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Strauss JF. Some new thoughts on the pathophysiology and genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 997: 42–8. Bibcode:2003NYASA.997...42S. PMID 14644808. doi:10.1196/annals.1290.005.

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Ada Hamosh. POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME 1; PCOS1. OMIM. McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. 12 September 2011 [15 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-16).

- ^ Amato P, Simpson JL. The genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004, 18 (5): 707–18. PMID 15380142. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.002.

- ^ Draper; et al. Mutations in the genes encoding 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase interact to cause cortisone reductase deficiency. Nature Genetics. 2003, 34: 434–439. PMID 12858176. doi:10.1038/ng1214.

- ^ Ehrmann David A. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352: 1223–1236. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041536.

- ^ Faghfoori Z, Fazelian S, Shadnoush M, Goodarzi R. Nutritional management in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A review study. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome (Review). 2017. PMID 28416368. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2017.03.030.

- ^ Dunaif A, Fauser BC. Renaming PCOS—a two-state solution. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98 (11): 4325–8. PMC 3816269 . PMID 24009134. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2040.

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Palioura E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Industrial endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2013, 36 (11): 1105–11. PMID 24445124. doi:10.1007/bf03346762.

- ^ Hoeger KM. Developmental origins and future fate in PCOS. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2014, 32 (3): 157–158. PMID 24715509. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1371086.

- ^ Harden CL. Polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome in epilepsy: evidence for neurogonadal disease. Epilepsy Curr. 2005, 5 (4): 142–6. PMC 1198730 . PMID 16151523. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00039.x.

- ^ Rasgon N. The relationship between polycystic ovary syndrome and antiepileptic drugs: a review of the evidence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004, 24 (3): 322–34. PMID 15118487. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000125745.60149.c6.

- ^ Hu X, Wang J, Dong W, Fang Q, Hu L, Liu C. A meta-analysis of polycystic ovary syndrome in women taking valproate for epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2011, 97 (1–2): 73–82. PMID 21820873. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.07.006.

- ^ Abbott DH, Barnett DK, Bruns CM, Dumesic DA. Androgen excess fetal programming of female reproduction: a developmental aetiology for polycystic ovary syndrome?. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2005, 11 (4): 357–74. PMID 15941725. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi013.

- ^ Rutkowska A, Rachoń D. Bisphenol A (BPA) and its potential role in the pathogenesis of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2014, 30 (4): 260–5. PMID 24397396. doi:10.3109/09513590.2013.871517.

- ^ Lewandowski KC, Cajdler-Łuba A, Salata I, Bieńkiewicz M, Lewiński A. The utility of the gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) test in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Endokrynol Pol. 2011, 62 (2): 120–8. PMID 21528473.

- ^ Munir, Iqbal; Yen, Hui-Wen; Geller, David H.; Torbati, Donna; Bierden, Rebecca M.; Weitsman, Stacy R.; Agarwal, Sanjay K.; Magoffin, Denis A. Insulin Augmentation of 17α-Hydroxylase Activity Is Mediated by Phosphatidyl Inositol 3-Kinase But Not Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase-1/2 in Human Ovarian Theca Cells. Endocrinology. January 2004, 145 (1): 175–183. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0329.

- ^ Diamanti-Kandarakis, Evanthia; Dunaif, Andrea. Insulin Resistance and the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Revisited: An Update on Mechanisms and Implications. Endocrine Reviews. December 2012, 33 (6): 981–1030. PMID 23065822. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1034.

- ^ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Marrinan, Greg. Lin, Eugene C , 编. Imaging in Polycystic Ovary Disease. eMedicine. eMedicine. 20 April 2011 [19 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-08).

- ^ Teede, Helena J; Tay, Chau Thien; Laven, Joop; Dokras, Anuja; Moran, Lisa J; Piltonen, Terhi T; Costello, Michael F; Boivin, Jacky; Redman, Leanne M; Boyle, Jacqueline A; Norman, Robert J. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Human Reproduction. 2023-09-05, 38 (9) [2024-02-06]. ISSN 0268-1161. PMC 10477934 . PMID 37580037. doi:10.1093/humrep/dead156. (原始内容存档于2024-07-31) (英语).

- ^ Teede, Helena J.; Tay, Chau Thien; Laven, Joop; Dokras, Anuja; Moran, Lisa J.; Piltonen, Terhi T.; Costello, Michael F.; Boivin, Jacky; M. Redman, Leanne; A. Boyle, Jacqueline; Norman, Robert.J. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2023-10, 120 (4) [2024-02-06]. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.07.025. (原始内容存档于2024-06-19) (英语).

- ^ Teede, Helena J; Tay, Chau Thien; Laven, Joop J E; Dokras, Anuja; Moran, Lisa J; Piltonen, Terhi T; Costello, Michael F; Boivin, Jacky; Redman, Leanne M; Boyle, Jacqueline A; Norman, Robert J. Recommendations From the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2023-09-18, 108 (10) [2024-02-06]. ISSN 0021-972X. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad463. (原始内容存档于2024-07-10) (英语).

- ^ Teede, Helena J; Tay, Chau Thien; Laven, Joop J E; Dokras, Anuja; Moran, Lisa J; Piltonen, Terhi T; Costello, Michael F; Boivin, Jacky; Redman, Leanne M; Boyle, Jacqueline A; Norman, Robert J. Recommendations from the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2023-08-02, 189 (2) [2024-02-06]. ISSN 0804-4643. doi:10.1093/ejendo/lvad096. (原始内容存档于2024-07-11) (英语).

- ^ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 48.7 Richard Scott Lucidi. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. eMedicine. 25 October 2011 [19 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-10).

- ^ Azziz R. Controversy in clinical endocrinology: diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome: the Rotterdam criteria are premature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91 (3): 781–5. PMID 16418211. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2153.

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19 (1): 41–7. PMID 14688154. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh098.

- ^ Carmina E. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: from NIH criteria to ESHRE-ASRM guidelines. Minerva Ginecol. 2004, 56 (1): 1–6. PMID 14973405.

- ^ Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S. Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004, 18 (5): 671–83. PMID 15380140. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.001.

- ^ Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Workup. eMedicine. 25 October 2011 [19 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-17).

- ^ Legro, Richard S.; Arslanian, Silva A.; Ehrmann, David A.; Hoeger, Kathleen M.; Murad, M. Hassan; Pasquali, Renato; Welt, Corrine K.; Endocrine Society. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. December 2013, 98 (12): 4565–4592. ISSN 1945-7197. PMC 5399492 . PMID 24151290. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2350.

- ^ Veltman-Verhulst SM, Boivin J, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BJ. Emotional distress is a common risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studies. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2012, 18 (6): 638–51. PMID 22824735. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms029.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 Moran LJ, Ko H, Misso M, Marsh K, Noakes M, Talbot M, Frearson M, Thondan M, Stepto N, Teede HJ. Dietary composition in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review to inform evidence-based guidelines. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2013, 19 (5): 432. PMID 23727939. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt015.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Treatment & Management. eMedicine. 25 October 2011 [19 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-16).

- ^ Krul-Poel YH, Snackey C, Louwers Y, Lips P, Lambalk CB, Laven JS, Simsek S. The role of vitamin D in metabolic disturbances in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. European Journal of Endocrinology (Review). 2013, 169 (6): 853–65. PMID 24044903. doi:10.1530/EJE-13-0617.

- ^ He C, Lin Z, Robb SW, Ezeamama AE. Serum Vitamin D Levels and Polycystic Ovary syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients (Meta-analysis). 2015, 7 (6): 4555–77. PMC 4488802 . PMID 26061015. doi:10.3390/nu7064555.

- ^ Huang, G; Coviello, A. Clinical update on screening, diagnosis and management of metabolic disorders and cardiovascular risk factors associated with polycystic ovary syndrome.. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. December 2012, 19 (6): 512–9. PMID 23108199. doi:10.1097/med.0b013e32835a000e.

- ^ Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ. Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003, 327 (7421): 951–3. PMC 259161 . PMID 14576245. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7421.951.

- ^ Li, X.-J.; Yu, Y.-X.; Liu, C.-Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.-J.; Yan, B.; Wang, L.-Y.; Yang, S.-Y.; Zhang, S.-H. Metformin vs thiazolidinediones for treatment of clinical, hormonal and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinical Endocrinology. 2011-03, 74 (3): 332–339. ISSN 1365-2265. PMID 21050251. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03917.x.

- ^ Grover, Anjali; Yialamas, Maria A. Metformin or thiazolidinedione therapy in PCOS?. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2011-03, 7 (3): 128– [2015-05-24]. ISSN 1759-5029. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.16. (原始内容存档于2015-07-22).

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 11 Clinical guideline 11 : Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems . London, 2004.

- ^ Balen A. Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PDF). Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 13. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. December 2008 [2009-12-13]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2009-12-18).

- ^ Leeman L, Acharya U. The use of metformin in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome and associated anovulatory infertility: the current evidence. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009, 29 (6): 467–72. PMID 19697191. doi:10.1080/01443610902829414.

- ^ Legro, RS; Arslanian, SA; Ehrmann, DA; Hoeger, KM; Murad, MH; Pasquali, R; Welt, CK; Endocrine, Society. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. December 2013, 98 (12): 4565–92. PMID 24151290. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2350.

- ^ Nestler, John E.; Jakubowicz, Daniela J.; Evans, William S.; Pasquali, Renato. Effects of Metformin on Spontaneous and Clomiphene-Induced Ovulation in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998-06-25, 338 (26): 1876–1880 [2015-05-24]. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 9637806. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806253382603.

- ^ Feig, Denice S.; Moses, Robert G. Metformin Therapy During Pregnancy Good for the goose and good for the gosling too?. Diabetes Care. 2011-10-01, 34 (10): 2329–2330 [2015-05-24]. ISSN 0149-5992. PMC 3177745 . PMID 21949224. doi:10.2337/dc11-1153. (原始内容存档于2015-05-25).

- ^ Cassina M, Donà M, Di Gianantonio E, Litta P, Clementi M. First-trimester exposure to metformin and risk of birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014, 20 (5): 656–69. PMID 24861556. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu022.

- ^ What are the health risks of PCOS?. Verity – PCOS Charity. Verity. 2011 [21 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2012年12月25日).

- ^ Richard Scott Lucidi. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Medication. eMedicine. 25 October 2011 [19 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-14).

- ^ Pundir, J; Psaroudakis, D; Savnur, P; Bhide, P; Sabatini, L; Teede, H; Coomarasamy, A; Thangaratinam, S. Inositol treatment of anovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. BJOG : An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 24 May 2017, 125 (3): 299–308. PMID 28544572. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14754.

- ^ Amoah-Arko, Afua; Evans, Meirion; Rees, Aled. Effects of myoinositol and D-chiro inositol on hyperandrogenism and ovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Endocrine Abstracts. 2017-10-20 [2019-02-22]. doi:10.1530/endoabs.50.P363. (原始内容存档于2018-08-12).

- ^ Galazis N, Galazi M, Atiomo W. D-Chiro-inositol and its significance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2011, 27 (4): 256–62. PMID 21142777. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.538099.

- ^ Unfer V, Carlomagno G, Dante G, Facchinetti F. Effects of myo-inositol in women with PCOS: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2012, 28 (7): 509–15. PMID 22296306. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.650660.

- ^ Zeng, Liuting; Yang, Kailin. Effectiveness of myoinositol for polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2017-10-19, 59 (1): 30–38. ISSN 1355-008X. PMID 29052180. doi:10.1007/s12020-017-1442-y.

- ^ Laganà, Antonio Simone; Vitagliano, Amerigo; Noventa, Marco; Ambrosini, Guido; D'Anna, Rosario. Myo-inositol supplementation reduces the amount of gonadotropins and length of ovarian stimulation in women undergoing IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2018-08-04, 298 (4): 675–684. ISSN 1432-0711. PMID 30078122. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4861-y.

- ^ Lim, Chi Eung Danforn; Ng, Rachel W. C.; Xu, Ke; Cheng, Nga Chong Lisa; Xue, Charlie C. L.; Liu, Jian Ping; Chen, Nini. Acupuncture for polycystic ovarian syndrome. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016-05-03, (5): CD007689. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 27136291. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007689.pub3.

- ^ Wu, XK; Stener-Victorin, E; Kuang, HY; Ma, HL; Gao, JS; Xie, LZ; Hou, LH; Hu, ZX; Shao, XG; Ge, J; Zhang, JF; Xue, HY; Xu, XF; Liang, RN; Ma, HX; Yang, HW; Li, WL; Huang, DM; Sun, Y; Hao, CF; Du, SM; Yang, ZW; Wang, X; Yan, Y; Chen, XH; Fu, P; Ding, CF; Gao, YQ; Zhou, ZM; Wang, CC; Wu, TX; Liu, JP; Ng, EHY; Legro, RS; Zhang, H; PCOSAct Study, Group. Effect of Acupuncture and Clomiphene in Chinese Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 27 June 2017, 317 (24): 2502–2514. PMC 5815063 . PMID 28655015. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7217.

- ^ 81.0 81.1 Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ. Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014, 20 (5): 748–758. PMC 4326303 . PMID 24688118. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu012.

- ^ New MI. Nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia and the polycystic ovarian syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 687: 193–205. Bibcode:1993NYASA.687..193N. PMID 8323173. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43866.x.

- ^ Hardiman P, Pillay OC, Atiomo W. Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial carcinoma. Lancet. 2003, 361 (9371): 1810–2. PMID 12781553. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13409-5.

- ^ Mather KJ, Kwan F, Corenblum B. Hyperinsulinemia in polycystic ovary syndrome correlates with increased cardiovascular risk independent of obesity. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73 (1): 150–6. PMID 10632431. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00468-9.

- ^ Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2010, 16 (4): 347–63. PMID 20159883. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq001.

- ^ Barry JA, Kuczmierczyk AR, Hardiman PJ. Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26 (9): 2442–51. PMID 21725075. doi:10.1093/humrep/der197.

- ^ Rocha MP, Maranhão RC, Seydell TM, Barcellos CR, Baracat EC, Hayashida SA, Bydlowski SP, Marcondes JA. Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and lipid transfer to high-density lipoprotein in young obese and normal-weight patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93 (6): 1948–56. PMID 19765700. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.044.

- ^ de Groot PC, Dekkers OM, Romijn JA, Dieben SW, Helmerhorst FM. PCOS, coronary heart disease, stroke and the influence of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2011, 17 (4): 495–500. PMID 21335359. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr001.

- ^ Goldenberg N, Glueck C. Medical therapy in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome before and during pregnancy and lactation. Minerva Ginecol. 2008, 60 (1): 63–75. PMID 18277353.

- ^ Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2008, 26 (1): 072–084. PMID 18181085. doi:10.1055/s-2007-992927.

- ^ Kachuei M, Jafari F, Kachuei A, Keshteli AH. Prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2012, 285 (3): 853–6. PMID 21866332. doi:10.1007/s00404-011-2040-5.

- ^ Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9859): 2163–96. PMID 23245607. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2.

- ^ Polson DW, Adams J, Wadsworth J, Franks S. Polycystic ovaries—a common finding in normal women. Lancet. 1988, 1 (8590): 870–2. PMID 2895373. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91612-1.

- ^ 94.0 94.1 Clayton RN, Ogden V, Hodgkinson J, Worswick L, Rodin DA, Dyer S, Meade TW. How common are polycystic ovaries in normal women and what is their significance for the fertility of the population?. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 1992, 37 (2): 127–34. PMID 1395063. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02296.x.

- ^ Farquhar CM, Birdsall M, Manning P, Mitchell JM, France JT. The prevalence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound scanning in a population of randomly selected women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994, 34 (1): 67–72. PMID 8053879. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1994.tb01041.x.

- ^ van Santbrink EJ, Hop WC, Fauser BC. Classification of normogonadotropic infertility: polycystic ovaries diagnosed by ultrasound versus endocrine characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 67 (3): 452–8. PMID 9091329. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)80068-4.

- ^ Hardeman J, Weiss BD. Intrauterine devices: an update.. Am Fam Physician. 2014, 89 (6): 445–50. PMID 24695563.

- ^ Azziz, Ricardo; Marin, Catherine; Hoq, Lalima; Badamgarav, Enkhe; Song, Paul. Health Care-Related Economic Burden of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome during the Reproductive Life Span. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1 August 2005, 90 (8): 4650–4658 [3 December 2018]. PMID 15944216. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0628. (原始内容存档于2018-12-04).

- ^ RCDC Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC). NIH. NIH. [3 December 2018]. (原始内容存档于2019-02-28).

- ^ What is Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)?. Verity – PCOS Charity. Verity. 2011 [21 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2012年12月24日).