比卡鲁胺

比卡鲁胺(英语:Bicalutamide)以Casodex(康士得)等品牌于市面销售,是种抗雄激素药物,主要用于治疗摄护腺癌。[10]它通常与促性腺激素释放激素调节剂 (GnRH) 类似物或睾丸切除术(去势)同时使用,以治疗转移性摄护腺癌 (mPC)。[11][10][12]在较不严重的案例,可用它作单一疗法,以高剂量治疗局部晚期摄护腺癌(LAPC),而无需进行去势。[4][2][13]比卡鲁胺曾被用作治疗局限性摄护腺癌 (LPC) 的单一疗法,但因临床试验结果不佳,核准遭到撤销。比卡鲁胺除用于治疗摄护腺癌之外,也被有限地用于治疗女性先天性遗传多毛症和雄激素性脱发,[14][15]并用于处理男性阴茎异常勃起。[16]此药物系透过口服方式给药。[10]

| |

| |

| 临床数据 | |

|---|---|

| 读音 | Bicalutamide: • /ˌbaɪkəˈluːtəmaɪd/[1] • BY-kə-LOO-tə-myde[1] |

| 商品名 | Casodex、Calutex及其他 |

| 其他名称 | ICI-176,334,ZD-176,334 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697047 |

| 核准状况 | |

| 怀孕分级 |

|

| 给药途径 | 口服给药[2] |

| 药物类别 | 非类固醇抗雄激素 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | 容易吸收,绝对生物利用度尚未知[3] |

| 血浆蛋白结合率 | 外消旋体: 96.1%[2] 对映异构: 99.6%[2] (主要与人类血清白蛋白结合)[2] |

| 药物代谢 | 肝脏 (广泛性):[4][9] • 羟基化 (CYP3A4) • 葡糖苷酸化 (UGT1A9酶) |

| 代谢产物 | • 比卡鲁胺葡糖苷酸 •羟基比卡鲁胺 • 羟基比卡鲁胺 葡糖苷酸 (全部非活性)[4][2][5][6] |

| 生物半衰期 | 单剂量: 5.8天[7] 持续使用: 7–10天[8] |

| 排泄途径 | 粪便: 43%[4] 尿液: 34%[4] |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 90357-06-5( 113299-40-4 ((R)-isomer) 113299-38-0 ((S)-isomer)) |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB配体ID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.126.100 |

| 化学信息 | |

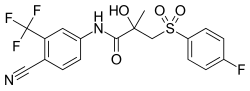

| 化学式 | C18H14F4N2O4S |

| 摩尔质量 | 430.37 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| 手性 | 外消旋体 (of (R)- and (S)-对映异构) |

| 熔点 | 191至193 °C(376至379 °F) (实验性) |

| 沸点 | 650 °C(1,202 °F) (推测) |

| 水溶性 | 0.005 |

| |

| |

使用后对男性的常见副作用有男性乳腺发育、乳房疼痛和潮热。[10]对男性的其他副作用有女性化和性功能障碍。[17][18]如进行过去势手术,有些副作用(例如乳腺发育和女性化)会大幅减少。[19]虽然该药物对女性产生的副作用似乎很少,但目前美国食品药物管理局 (FDA) 尚未明确批准提供女性使用。[20][10]个体于怀孕期间使用此药物可能会伤害胎儿。[10]在罹患早期摄护腺癌的男性中,使用比卡鲁胺单一疗法会增加摄护腺癌以外原因导致死亡的可能性。[21][13]比卡鲁胺会导致约1%的使用者出现异常肝脏变化(转氨酶升高)而须停止用药。[22][13]罕见的情况有与严重肝损伤、[10]严重肺毒性、[3]和对光敏感的案例有关联。[23][24]虽然肝脏发生不良变化的风险很小,仍建议在治疗期间进行肝功能检测。[10]

比卡鲁胺是种非类固醇抗雄激素 (NSAA) 类药物。[3]它透过选择性阻断雄激素受体 (AR) 而发挥作用。[25]人体对比卡鲁胺的吸收度良好,饮食期间服用并不受影响。[2]药物的生物半衰期约为一周。[2][10]它在动物体内是种周边选择性药物,但对人类而言,则会穿过血脑屏障并对身体和大脑产生影响。[2][26]

比卡鲁胺于1982年取得专利,于1995年获准用于医疗用途,[27]并已被列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单中。[28]市面已有通用名药物贩售。[29]该药物在80多个国家(包括大多数发达国家)流通。[30][31][32]

医疗用途

编辑比卡鲁胺主要用于以下适应症:[33]

- 男性转移性摄护腺癌 (mPC) ,同时摄取促性腺激素释放激素调节剂 (GnRH) 类似物或是与去势手术联合使用,每日摄取50毫克。[22][4][34]

- 男性局部晚期摄护腺癌 (LAPC) 单一疗法,每日摄取150毫克(美国并未批准此种用途)[4][2][13][35]

日本核准的治疗摄护腺癌,药物使用剂量为每日80毫克,既可与去势手术结合使用,也可作单一疗法使用。[36][37]

比卡鲁胺的仿单标示外使用适应症有:

- 减少男性接受GnRH激动剂治疗开始时睾酮激增的影响。[38][39]

- 雄激素依赖性皮肤和毛发疾病,如女性痤疮、皮脂分泌旺盛、先天性遗传多毛症和雄激素性脱发,以及女性多囊卵巢综合征 (PCOS) 导致的高睾酮水平,通常会与避孕药联合使用,比卡鲁胺的用量为每日25至50毫克。[14][40][41][42][43][44][45]

- 为跨性别女性进行女性化激素疗法,通常与雌激素合并使用,剂量为每日50毫克。[46][47][48][49][50][51][52]

- 男孩周边性早熟(特别是家族性男性限定性性早熟(睾丸毒性),每日服用12.5至100毫克,与芳香化酶抑制剂(如阿那曲唑)联合使用。[22][53][54][55][56][57][58]

- 男性阴茎异常勃起,每周摄取50毫克至每隔一天摄取50毫克。[59][60][61][62][3][7][16]

此药物已被建议用于以下适应症,但效果尚不确定:

配方形式

编辑比卡鲁胺在全球80多个国家(大多数为发达国家)经核准用于治疗摄护腺癌。[69][30][70][31][32]有50毫克、80毫克(在日本)[36]和150毫克口服片剂形式。该药物在至少55个国家注册为每日150毫克的单一疗法,以治疗男性局部晚期摄护腺癌,[2]但在美国是一明显例外,该药物仅注册为每日50毫克的剂量,结合去势使用。[71]

禁忌症

编辑比卡鲁胺在美国属于妊娠X类,即"妊娠禁忌",[22]在"澳大利亚"属于妊娠D类,即第二大限制级别。[72]因此怀孕期间的女性禁用比卡鲁胺,强烈建议性活跃且能够或可能怀孕的女性仅在采取适当避孕措施的情况下才能服用比卡鲁胺。[73][74]目前尚不清楚比卡鲁胺是否会进入母乳中,但同样不建议在个体进行母乳哺育时使用比卡鲁胺。[3][22]

对患有严重肝病的个体,有证据显示人体消除比卡鲁胺的速度会减慢,由于体内比卡鲁胺的水平可能会因此增加,患者需要谨慎。[2][75]比卡鲁胺的生物半衰期在肾功能损害患者体中并无变化。[71]

副作用

编辑比卡鲁胺的副作用很大程度上取决于性别。在男性中,由于雄激素缺乏症,有不同严重程度的副作用会出现,最常见的是乳房疼痛/压痛和乳腺发育。 在接受比卡鲁胺单一药物治疗的男性中,高达80%的男性会出现乳腺发育,超过90%的乳腺发育的严重程度为轻度至中度。[76][77]其他与雄性素缺乏类似的副作用有潮热、性功能障碍(例如性冲动丧失、勃起功能障碍)、忧郁、疲劳、虚弱和贫血。[78][79][80]

比卡鲁胺与肝功能检查异常结果(例如肝脏酵素水平升高)有关联。[79][13]建议在治疗期间监测肝功能,特别是在最初的几个月。[13][78]在患有早期摄护腺癌的男性中,发现使用比卡鲁胺单一疗法会增加非摄护腺癌原因的死亡率。[21][81][13]这些死亡率增加的原因尚不清楚,可能的因素包括雄激素缺乏或比卡鲁胺药物相关毒性。[82][83]

截至2022年,已有10例与比卡鲁胺相关的肝毒性病例报告提出。[84][85][86][87]

由于比卡鲁胺是一种抗雄激素,理论上存在导致男性胎儿先天性障碍的风险,例如生殖器不明确。[73][74][88][89]由于这种可能的致畸能力,具有生育能力和性活跃的女性于服用比卡鲁胺时,应采取避孕措施。[90]

过量

编辑尚未确定人类单次摄取比卡鲁胺会导致过量症状,或被认为会危及生命。[22][91]在临床试验中,高达每日600毫克的剂量仍受到良好耐受。[92]

与其他药物交互作用

编辑比卡鲁胺几乎完全由肝脏的CYP3A4代谢。[4]因此CYP3A4的抑制剂和诱导剂可能会改变药物在体内的水平。[7]虽然比卡鲁胺是由CYP3A4代谢,但没证据显示使用剂量为每日150毫克或更少,而同时使用其他引发或抑制CYP3A4的药物后会发生临床上显著的药物交互作用。[13]

由于比卡鲁胺以相对较高的浓度在人体中循环,且具有高度蛋白质结合力,因此有可能取代血浆中华法林、苯妥英、茶碱和阿司匹林等其他具高度蛋白质结合力的药物。[76][79]

药理学

编辑药效学

编辑药物动力学

编辑此药物在人体中的绝对生物利用度尚未被完全了解,[2][3]但已知比卡鲁胺具有广泛且吸收良好的特性。其吸收不受患者进行饮食的影响。[3][93]

比卡鲁胺的药物动力学不受同时进食、年龄或体重、肾功能损害或轻至中度肝功能损害的影响。[2][94]然而服用此药物的日本人,其体内药物的稳态水准会高于白人的。[2]

化学性质

编辑类似物

编辑第一代非类固醇抗雄激素药物包括比卡鲁胺、氟他胺和尼鲁米特,都是合成的非类固醇苯胺(抗雄激素)衍生物,并且彼此具有类似结构。[95]

合成

编辑已有许多文献提出比卡鲁胺的化学合成法。[96][97][98][99][100]首次发表的比卡鲁胺的合成过程如下图所示。[97]

Bicalutamide synthesis[97]

|

历史

编辑比卡鲁胺以及目前上市的所有非类固醇抗雄激素药物均源自氟他胺的结构修饰,氟他胺本身最初于1967年由先灵葆雅公司合成,作抑菌剂用途,而后偶然发现其具有抗雄激素活性。[101][102][103]比卡鲁胺由在帝国化学工业 (ICI) 工作的Tucker及其同事于20世纪80年代从超过2,000种合成化合物筛选后开发而成。[104][105][106][96]此化合物于1982年首次获得专利,[107]并于1987年6月首次在科学文献中提出报告。[108]

比卡鲁胺为通用名称,在各种国际性及国家性药典/名称登记中均被使用。[109][72][30][110][69][111]

社会与文化

编辑品牌名称

编辑有Casodex、Cosudex、Calutide、Calumid和Kalumi等。[30][69][112][113]

通用名药物

编辑比卡鲁胺已不受专利保护,市面有众多通用名药物流通,[114]而且价格较为便宜。[115][116]

销售

编辑比卡鲁胺(如Casodex)的全球销售额于2007年达到13亿美元的峰值,[117]在2007年失去专利保护之前,它是种"每年销售达十亿美元"的药物之一。[118][119][120]比卡鲁胺仍然是转移性摄护腺癌经去势手术后最常用的处方药。[118]

于2007年到2009的两年间,在美国开立的NSAA处方笺中,比卡鲁胺约占87.2%,氟他胺占10.5%,尼鲁米特占2.3%。[121]

研究

编辑目前有将比卡鲁胺与5α-还原酶抑制剂非那雄胺和度他雄胺联合,以治疗摄护腺癌的研究。[122][123][124][125][126][127][128]它也与雷洛昔芬(一种选择性雌激素受体调节物(SERM))联合用于治疗摄护腺癌。[129][130]

有使用抗雄激素药物治疗男性COVID-19的提议,截至2020年5月,使用高剂量比卡鲁胺的疗法正处于II期临床试验中。[131][132]

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ 1.0 1.1 Finkel R, Clark MA, Cubeddu LX. Pharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009: 481–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7155-9.

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Cockshott ID. Bicalutamide: clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2004, 43 (13): 855–878. PMID 15509184. S2CID 29912565. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00003.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Dart RC. Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004: 497, 521. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. (原始内容存档于11 May 2016).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Lemke TL, Williams DA. Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008: 121, 1288, 1290. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ Dole EJ, Holdsworth MT. Nilutamide: an antiandrogen for the treatment of prostate cancer. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 1997, 31 (1): 65–75. PMID 8997470. S2CID 20347526. doi:10.1177/106002809703100112.

page 67: Currently, information is not available regarding the activity of the major urinary metabolites of bicalutamide, bicalutamide glucuronide, and hydroxybicalutamide glucuronide.

- ^ Schellhammer PF. An evaluation of bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. September 2002, 3 (9): 1313–28. PMID 12186624. S2CID 32216411. doi:10.1517/14656566.3.9.1313.

The clearance of bicalutamide occurs pre- dominantly by hepatic metabolism and glucuronidation, with excretion of the resulting inactive metabolites in the urine and faces.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Skidmore-Roth L. Mosby's 2014 Nursing Drug Reference – Elsevieron VitalSource. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013-04-17: 193–194 [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-0-323-22267-9. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ Jordan VC, Furr BJ. Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. 2010-02-05: 350–. ISBN 978-1-59259-152-7. (原始内容存档于2016-05-29).

- ^ Grosse L, Campeau AS, Caron S, Morin FA, Meunier K, Trottier J, Caron P, Verreault M, Barbier O. Enantiomer selective glucuronidation of the non-steroidal pure anti-androgen bicalutamide by human liver and kidney: role of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A9 enzyme. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. August 2013, 113 (2): 92–102. PMC 3815647 . PMID 23527766. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12071.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Bicalutamide. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [2016-12-08]. (原始内容存档于2016-12-29).

- ^ Wass JA, Stewart PM. Oxford Textbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes. OUP Oxford. 2011-07-28: 1625–. ISBN 978-0-19-923529-2. (原始内容存档于2016-05-11).

- ^ Shergill I, Arya M, Grange PR, Mundy AR. Medical Therapy in Urology. Springer Science & Business Media. 2010: 40. ISBN 9781848827042. (原始内容存档于28 October 2014) (英语).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Wellington K, Keam SJ. Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer (PDF). Drugs. 2006, 66 (6): 837–50 [2016-08-13]. PMID 16706554. S2CID 46966712. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-08-28).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Williams H, Bigby M, Diepgen T, Herxheimer A, Naldi L, Rzany B. Evidence-Based Dermatology. John Wiley & Sons. 2009-01-22: 529–. ISBN 978-1-4443-0017-8. (原始内容存档于2016-05-02).

- ^ Carvalho RM, Santos LD, Ramos PM, Machado CJ, Acioly P, Frattini SC, Barcaui CB, Donda AL, Melo DF. Bicalutamide and the new perspectives for female pattern hair loss treatment: What dermatologists should know. J Cosmet Dermatol. January 2022, 21 (10): 4171–4175. PMID 35032336. S2CID 253239337. doi:10.1111/jocd.14773.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Yuan J, Desouza R, Westney OL, Wang R. Insights of priapism mechanism and rationale treatment for recurrent priapism. Asian Journal of Andrology. 2008, 10 (1): 88–101. PMID 18087648. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00314.x .

- ^ Elliott S, Latini DM, Walker LM, Wassersug R, Robinson JW. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: recommendations to improve patient and partner quality of life. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010, 7 (9): 2996–3010. PMID 20626600. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01902.x.

- ^ Hammerer P, Manka L. Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Advanced Prostate Cancer. Urologic Oncology. Springer International Publishing. 2019: 255–276. ISBN 978-3-319-42622-8. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42623-5_77.

Bicalutamide is the most widely used antiandrogen in the treatment of prostate cancer. [...] Common side effects [of bicalutamide] include breast enlargement, breast tenderness, hot flashes, and constipation as well as feminization and changes in mood and liver as well as lung toxicity; monitoring of liver enzymes is recommended during treatment (Schellhammer and Davis 2004).

- ^ Droz J, Audisio RA. Management of Urological Cancers in Older People. Springer Science & Business Media. 2012-10-02: 84–. ISBN 978-0-85729-986-4. (原始内容存档于2016-05-11).

- ^ Shapiro J. Hair Disorders: Current Concepts in Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, An Issue of Dermatologic Clinics. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2012-11-12: 187–. ISBN 978-1-4557-7169-1.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Jia AY, Spratt DE. Bicalutamide Monotherapy With Radiation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: A Non-Evidence-Based Alternative. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. June 2022, 113 (2): 316–319. PMID 35569476. S2CID 248765294. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.01.037.

Four other randomized trials using BICmono have also raised concerns about either lack of efficacy or even harm from this treatment approach compared with placebo or no hormone therapy. SPCG-6 randomized 1218 patients to either 150 mg of BICmono daily or placebo. In the subset of patients with LPCa managed with observation, survival was significantly worse with BIC than placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.03).10 Two other randomized trials were part of the early prostate cancer program,11 which conducted 3 randomized trials that were pooled together to determine the benefit of BICmono (SPCG-6 was one of the 3 trials). Overall, in the combined 8113 patient pooled cohort, after a median follow-up of 7 years, there was no improvement even in progression-free survival from the use of adjuvant BIC in LPCa, and there was a trend for worse overall survival (HR, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 0.99-1.37; P = .07). [...] Although not in LPCa, NRG/RTOG 9601 demonstrated findings consistent with the prior trials.12 This trial randomized men to postprostatectomy salvage radiation therapy plus placebo versus 150 mg of BICmono daily for 2 years. After a median follow-up of 13 years, the trial showed that there were significantly more grade 3 to 5 cardiac events in the BICmono arm. In patients with less aggressive disease with lower PSAs (prostate-specific antigens; more analogous to LPCa), other-cause mortality was significantly higher in the BICmono arm. In patients with high PSAs >1.5 ng/mL (which with modern molecular positron emission tomography imaging would be expected to have high rates of regional and distant metastatic disease), a survival benefit from the addition of BIC was observed. This is consistent with results from the early prostate cancer studies that showed that only patients with more advanced disease derived benefit from BICmono.10 Thus, all the randomized evidence from 5 trials (Table 1) demonstrates that, in LPCa, BICmono had no clinically significant oncologic activity over placebo/no treatment, and consistent trends with long-term use resulted in worse survival.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Casodex- bicalutamide tablet. DailyMed. 2019-09-01 [2020-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-27).

- ^ Lee K, Oda Y, Sakaguchi M, Yamamoto A, Nishigori C. Drug-induced photosensitivity to bicalutamide – case report and review of the literature. Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. May 2016, 32 (3): 161–4. PMID 26663090. S2CID 2761388. doi:10.1111/phpp.12230.

- ^ Lee K, et al. Drug-induced photosensitivity to bicalutamide – case report and review of the literature. Reactions Weekly. 2016, 1612 (1): 161–4. PMID 26663090. S2CID 261402820. doi:10.1007/s40278-016-19790-1.

- ^ Singh SM, Gauthier S, Labrie F. Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships. Current Medicinal Chemistry. February 2000, 7 (2): 211–47. PMID 10637363. doi:10.2174/0929867003375371.

- ^ Furr BJ, Tucker H. The preclinical development of bicalutamide: pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action. Urology. January 1996, 47 (1A Suppl): 13–25; discussion 29–32. PMID 8560673. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80003-3.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR. Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006: 515 [2017-08-24]. ISBN 9783527607495. (原始内容存档于2023-01-12) (英语).

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771 . WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Hamilton R. Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2015: 381. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Bicalutamide – International Drug Names. Drugs.com. [2016-08-13]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-18).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Akaza H. [A new anti-androgen, bicalutamide (Casodex), for the treatment of prostate cancer—basic clinical aspects]. Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer & Chemotherapy. 1999, 26 (8): 1201–7. PMID 10431591 (日语).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 1999 Annual Report and Form 20-F (PDF). AstraZeneca. [2017-07-01]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-09-09).

- ^ Bagatelle C, Bremner WJ. Androgens in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. 2003-05-27: 25–. ISBN 978-1-59259-388-0.

- ^ Klotz L, Schellhammer P. Combined androgen blockade: the case for bicalutamide. Clinical Prostate Cancer. March 2005, 3 (4): 215–9. PMID 15882477. doi:10.3816/cgc.2005.n.002.

- ^ Schellhammer PF, Sharifi R, Block NL, Soloway MS, Venner PM, Patterson AL, Sarosdy MF, Vogelzang NJ, Schellenger JJ, Kolvenbag GJ. Clinical benefits of bicalutamide compared with flutamide in combined androgen blockade for patients with advanced prostatic carcinoma: final report of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter trial. Casodex Combination Study Group. Urology. September 1997, 50 (3): 330–6. PMID 9301693. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00279-3.

- ^ 36.0 36.1 Suzuki H, Kamiya N, Imamoto T, Kawamura K, Yano M, Takano M, Utsumi T, Naya Y, Ichikawa T. Current topics and perspectives relating to hormone therapy for prostate cancer. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. October 2008, 13 (5): 401–10. PMID 18946750. S2CID 32859879. doi:10.1007/s10147-008-0830-y.

- ^ Usami M, Akaza H, Arai Y, Hirano Y, Kagawa S, Kanetake H, Naito S, Sumiyoshi Y, Takimoto Y, Terai A, Yoshida H, Ohashi Y. Bicalutamide 80 mg combined with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (LHRH-A) versus LHRH-A monotherapy in advanced prostate cancer: findings from a phase III randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial in Japanese patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007, 10 (2): 194–201. PMID 17199134. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500934 .

In most countries, bicalutamide is given at a dose of 50 mg when used in combination with an LHRH-A. However, based on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, the approved dose of bicalutamide in Japanese men is 80 mg per day.

- ^ Melmed S. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016-01-01: 752–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7.

GnRH analogues, both agonists and antagonists, severely suppress endogenous gonadotropin and testosterone production [...] Administration of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide, goserelin) produces an initial stimulation of gonadotropin and testosterone secretion (known as a "flare"), which is followed in 1 to 2 weeks by GnRH receptor downregulation and marked suppression of gonadotropins and testosterone to castration levels. [...] To prevent the potential complications associated with the testosterone flare, AR antagonists (e.g., bicalutamide) are usually coadministered with a GnRH agonist for men with metastatic prostate cancer.399

- ^ Sugiono M, Winkler MH, Okeke AA, Benney M, Gillatt DA. Bicalutamide vs cyproterone acetate in preventing flare with LHRH analogue therapy for prostate cancer—a pilot study. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 2005, 8 (1): 91–4. PMID 15711607. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500784 .

- ^ Erem C. Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2013, 68 (4): 268–74. PMID 24455796. S2CID 39120534. doi:10.2143/ACB.3267.

- ^ Ascenso A, Marques HC. Acne in the adult. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. January 2009, 9 (1): 1–10. PMID 19149656. doi:10.2174/138955709787001730.

- ^ Kaur S, Verma P, Sangwan A, Dayal S, Jain VK. Etiopathogenesis and Therapeutic Approach to Adult Onset Acne. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2016, 61 (4): 403–7. PMC 4966398 . PMID 27512185. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.185703 .

- ^ Lotti F, Maggi M. Hormonal Treatment for Skin Androgen-Related Disorders. European Handbook of Dermatological Treatments. 2015: 1451–1464. ISBN 978-3-662-45138-0. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-45139-7_142.

- ^ Müderris II, Öner G. Hirsutizm Tedavisinde Flutamid ve Bikalutamid Kullanımı [Flutamide and Bicalutamide Treatment in Hirsutism]. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Endocrinology-Special Topics. 2009, 2 (2): 110–2 [2019-03-28]. ISSN 1304-0529. (原始内容存档于2020-07-27) (土耳其语).

- ^ Moretti C, Guccione L, Di Giacinto P, Simonelli I, Exacoustos C, Toscano V, Motta C, De Leo V, Petraglia F, Lenzi A. Combined Oral Contraception and Bicalutamide in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Severe Hirsutism: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. March 2018, 103 (3): 824–838. PMID 29211888. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01186 .

- ^ Randolph JF. Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy for Transgender Females. Clin Obstet Gynecol. December 2018, 61 (4): 705–721. PMID 30256230. S2CID 52821192. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396.

- ^ Fishman SL, Paliou M, Poretsky L, Hembree WC. Endocrine Care of Transgender Adults. Transgender Medicine. Contemporary Endocrinology. 2019: 143–163. ISBN 978-3-030-05682-7. ISSN 2523-3785. S2CID 86772102. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05683-4_8.

- ^ Neyman A, Fuqua JS, Eugster EA. Bicalutamide as an Androgen Blocker With Secondary Effect of Promoting Feminization in Male-to-Female Transgender Adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health. April 2019, 64 (4): 544–546. PMC 6431559 . PMID 30612811. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.296.

- ^ Gooren LJ. Clinical practice. Care of transsexual persons. The New England Journal of Medicine. March 2011, 364 (13): 1251–1257. PMID 21449788. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1008161.

- ^ Deutsch M. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People (PDF) 2nd. University of California, San Francisco: Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. 2016-06-17: 28 [2023-06-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-05-30).

- ^ Vincent B. Transgender Health: A Practitioner's Guide to Binary and Non-Binary Trans Patient Care. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2018-06-21: 158– [2019-01-01]. ISBN 978-1-78450-475-5. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ Wierckx K, Gooren L, T'Sjoen G. Clinical review: Breast development in trans women receiving cross-sex hormones. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. May 2014, 11 (5): 1240–1247. PMID 24618412. doi:10.1111/jsm.12487.

- ^ Schoelwer M, Eugster EA. Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty. Puberty from Bench to Clinic. Endocrine Development 29. 2015: 230–239. ISBN 978-3-318-02788-4. PMC 5345994 . PMID 26680582. doi:10.1159/000438895.

- ^ Haddad NG, Eugster EA. Peripheral precocious puberty including congenital adrenal hyperplasia: causes, consequences, management and outcomes. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. June 2019, 33 (3): 101273. PMID 31027974. S2CID 135410503. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2019.04.007. hdl:1805/19111 .

- ^ Haddad NG, Eugster EA. Peripheral Precocious Puberty: Interventions to Improve Growth. Handbook of Growth and Growth Monitoring in Health and Disease. 2012: 1199–1212. ISBN 978-1-4419-1794-2. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1795-9_71.

- ^ Zacharin M. Disorders of Puberty: Pharmacotherapeutic Strategies for Management. Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 261. 2019: 507–538. ISBN 978-3-030-50493-9. ISSN 0171-2004. PMID 31144045. S2CID 169040406. doi:10.1007/164_2019_208.

- ^ Kliegman RM, Stanton B, St Geme J, Schor NF. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. 17 April 2015: 2661– [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-0-323-26352-8. (原始内容存档于2023-01-12).

- ^ Jameson JL, De Groot LJ. Edndocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. 25 February 2015: 2425–2426, 2139. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2.

- ^ Levey HR, Kutlu O, Bivalacqua TJ. Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature. Asian Journal of Andrology. January 2012, 14 (1): 156–163. PMC 3753435 . PMID 22057380. doi:10.1038/aja.2011.114.

- ^ Broderick GA, Kadioglu A, Bivalacqua TJ, Ghanem H, Nehra A, Shamloul R. Priapism: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. January 2010, 7 (1 Pt 2): 476–500. PMID 20092449. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01625.x.

- ^ Chow K, Payne S. The pharmacological management of intermittent priapismic states. BJU International. December 2008, 102 (11): 1515–1521. PMID 18793304. S2CID 35399393. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07951.x .

- ^ Dahm P, Rao DS, Donatucci CF. Antiandrogens in the treatment of priapism. Urology. January 2002, 59 (1): 138. PMID 11796309. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01492-3.

- ^ Gooren LJ. Clinical review: Ethical and medical considerations of androgen deprivation treatment of sex offenders. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011, 96 (12): 3628–37. PMID 21956411. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-1540 .

- ^ Giltay EJ, Gooren LJ. Potential side effects of androgen deprivation treatment in sex offenders. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2009, 37 (1): 53–8. PMID 19297634.

- ^ Khan O, Mashru A. The efficacy, safety and ethics of the use of testosterone-suppressing agents in the management of sex offending. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2016, 23 (3): 271–8. PMID 27032060. S2CID 43286710. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000257.

- ^ Dangerous Sex Offenders: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Pub. 1999: 111–. ISBN 978-0-89042-280-9.

- ^ Houts FW, Taller I, Tucker DE, Berlin FS. Androgen deprivation treatment of sexual behavior. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011, 31: 149–63. ISBN 978-3-8055-9825-5. PMID 22005210. doi:10.1159/000330196.

- ^ Rousseau L, Couture M, Dupont A, Labrie F, Couture N. Effect of combined androgen blockade with an LHRH agonist and flutamide in one severe case of male exhibitionism. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1990, 35 (4): 338–41. PMID 2189544. S2CID 28970865. doi:10.1177/070674379003500412.

- ^ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Swiss Pharmaceutical Society (编). Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000: 123–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. (原始内容存档于2016-04-24).

- ^ Sweetman SC. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. 2011: 750–751 [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-0-85369-933-0. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ 71.0 71.1 Chabner BA, Longo DL. Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010-11-08: 679–680 [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-1-60547-431-1. (原始内容存档于2023-01-10).

From a structural standpoint, antiandrogens are classified as steroidal, including cyproterone [acetate] (Androcur) and megestrol [acetate], or nonsteroidal, including flutamide (Eulexin, others), bicalutamide (Casodex), and nilutamide (Nilandron). The steroidal antiandrogens are rarely used.

- ^ 72.0 72.1 COSUDEX® (bicalutamide) 150 mg tablets. TGA. (原始内容存档于2016-09-14).

- ^ 73.0 73.1 Iswaran TJ, Imai M, Betton GR, Siddall RA. An overview of animal toxicology studies with bicalutamide (ICI 176,334). The Journal of Toxicological Sciences. May 1997, 22 (2): 75–88. PMID 9198005. doi:10.2131/jts.22.2_75 .

- ^ 74.0 74.1 Smith RE. Medicinal Chemistry – Fusion of Traditional and Western Medicine. Bentham Science Publishers. 2013-04-04: 306–. ISBN 978-1-60805-149-6. (原始内容存档于2016-05-29).

- ^ Skeel RT, Khleif SN. Handbook of Cancer Chemotherapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011: 724–. ISBN 9781608317820. (原始内容存档于2016-05-29).

- ^ 76.0 76.1 Wirth MP, Hakenberg OW, Froehner M. Antiandrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer. European Urology. February 2007, 51 (2): 306–13; discussion 314. PMID 17007995. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.043.

- ^ Wellington K, Keam SJ. Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer. Drugs. 2006, 66 (6): 837–50. PMID 16706554. S2CID 46966712. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Lehne RA. Pharmacology for Nursing Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013: 1297– [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-1-4377-3582-6. (原始内容存档于2023-01-10).

- ^ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Kolvenbag GJ, Blackledge GR. Worldwide activity and safety of bicalutamide: a summary review. Urology. January 1996, 47 (1A Suppl): 70–9; discussion 80–4. PMID 8560681. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(96)80012-4.

Bicalutamide is a new antiandrogen that offers the convenience of once-daily administration, demonstrated activity in prostate cancer, and an excellent safety profile. Because it is effective and offers better tolerability than flutamide, bicalutamide represents a valid first choice for antiandrogen therapy in combination with castration for the treatment of patients with advanced prostate cancer.

- ^ Resnick MI, Thompson IM. Advanced Therapy of Prostate Disease. PMPH-USA. 2000: 379–. ISBN 978-1-55009-102-1. (原始内容存档于2016-06-10).

- ^ Iversen P, Johansson JE, Lodding P, Lukkarinen O, Lundmo P, Klarskov P, Tammela TL, Tasdemir I, Morris T, Carroll K. Bicalutamide (150 mg) versus placebo as immediate therapy alone or as adjuvant to therapy with curative intent for early nonmetastatic prostate cancer: 5.3-year median followup from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 6. The Journal of Urology. November 2004, 172 (5 Pt 1): 1871–6. PMID 15540741. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000139719.99825.54.

- ^ Wellington K, Keam SJ. Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer. Drugs. 2006, 66 (6): 837–50. PMID 16706554. S2CID 46966712. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007.

- ^ Iversen P, Johansson JE, Lodding P, Kylmälä T, Lundmo P, Klarskov P, Tammela TL, Tasdemir I, Morris T, Armstrong J. Bicalutamide 150 mg in addition to standard care for patients with early non-metastatic prostate cancer: updated results from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Period Group-6 Study after a median follow-up period of 7.1 years. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2006, 40 (6): 441–52. PMID 17130095. S2CID 25862814. doi:10.1080/00365590601017329.

- ^ Trüeb RM, Luu NC, Uribe NC, Régnier A. Comment on: Bicalutamide and the new perspectives for female pattern hair loss treatment: What dermatologists should know. J Cosmet Dermatol. December 2022, 21 (12): 7200–7201. PMID 35332669. S2CID 247677549. doi:10.1111/jocd.14936.

Indeed, due to the minimal biological importance of androgens in women, the adverse effects of bicalutamide are few. And yet, bicalutamide has been associated with elevated liver enzymes, and as of 2021, there have been 10 case reports of liver toxicity associated with bicalutamide, with fatality occurring in 2 cases.2

- ^ Gretarsdottir HM, Bjornsdottir E, Bjornsson ES. Bicalutamide-Associated Acute Liver Injury and Migratory Arthralgia: A Rare but Clinically Important Adverse Effect. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2018, 12 (2): 266–70. ISSN 1662-0631. doi:10.1159/000485175 . hdl:20.500.11815/1492 .

- ^ Hussain S, Haidar A, Bloom RE, Zayouna N, Piper MH, Jafri SM. Bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: A rare adverse effect. Am J Case Rep. 2014, 15: 266–70. PMC 4068966 . PMID 24967002. doi:10.12659/AJCR.890679.

- ^ Yun GY, Kim SH, Kim SW, Joo JS, Kim JS, Lee ES, Lee BS, Kang SH, Moon HS, Sung JK, Lee HY, Kim KH. Atypical onset of bicalutamide-induced liver injury. World J. Gastroenterol. April 2016, 22 (15): 4062–5. PMC 4823258 . PMID 27099451. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.4062 .

- ^ Sex Differences in the Human Brain, their underpinnings and implications. Elsevier. 2010-12-03: 44–45. ISBN 978-0-444-53631-0. (原始内容存档于2016-05-26).

- ^ Paoletti R. Chemistry and Brain Development: Proceedings of the Advanced Study Institute on "Chemistry of Brain Development," held in Milan, Italy, September 9–19, 1970. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012: 218– [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-1-4684-7236-3. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ Papadimitriou K, Anagnostis P, Goulis DG. The challenging role of antiandrogens in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Elsevier. 2022: 297–314. ISBN 9780128230459. S2CID 244697776. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-823045-9.00013-4.

- ^ Nurse Practitioner's Drug Handbook. Springhouse Corp. 2000 [2016-09-27]. ISBN 9780874349979. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ Tyrrell CJ, Iversen P, Tammela T, Anderson J, Björk T, Kaisary AV, Morris T. Tolerability, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of bicalutamide 300 mg, 450 mg or 600 mg as monotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer, compared with castration. BJU International. September 2006, 98 (3): 563–72. PMID 16771791. S2CID 41672303. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06275.x.

- ^ Weber GF. Molecular Therapies of Cancer. Springer. 2015-07-22: 318–. ISBN 978-3-319-13278-5.

Compared to flutamide and nilutamide, bicalutamide has a 2-fold increased affinity for the Androgen Receptor, a longer half-life, and substantially reduced toxicities. Based on a more favorable safety profile relative to flutamide, bicalutamide is indicated for use in combination therapy with a Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone analog for the treatment of advanced metastatic prostate carcinoma.

- ^ Denis L, Mahler C. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of bicalutamide: defining an active dosing regimen. Urology. January 1996, 47 (1A Suppl): 26–8; discussion 29–32. PMID 8560674. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80004-5.

- ^ Mohler ML, Bohl CE, Jones A, Coss CC, Narayanan R, He Y, Hwang DJ, Dalton JT, Miller DD. Nonsteroidal selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs): dissociating the anabolic and androgenic activities of the androgen receptor for therapeutic benefit. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. June 2009, 52 (12): 3597–617. PMID 19432422. doi:10.1021/jm900280m.

[C]linically relevant antiandrogens currently are nonsteroidal anilide derivatives. Antiandrogens used for prostate cancer include the monoarylpropionamide flutamide (1) (a prodrug of hydroxyflutamide (2)),29–31 the hydantoin nilutamide(3),32–34 and the diarylpropionamide bicalutamide (4) (Chart1).35–37

- ^ 96.0 96.1 McPherson EM. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia 3rd. William Andrew Publishing. 2013-10-22: 627, 1695. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3. (原始内容存档于2016-06-09).

- ^ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Tucker H, Crook JW, Chesterson GJ. Nonsteroidal antiandrogens. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 3-substituted derivatives of 2-hydroxypropionanilides. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1988, 31 (5): 954–9. PMID 3361581. doi:10.1021/jm00400a011.

- ^ James KD, Ekwuribe NN. A Two-step Synthesis of the Anti-cancer Drug (R,S)-Bicalutamide. Synthesis. 2002, 2002 (7): 850–2. doi:10.1055/s-2002-28508.

- ^ US application 2006/0041161,Pizzetti E, Vigano E, Lussana M, Landonio E,“Procedure for the synthesis of bicalutamide”,发表于2006-02-23 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2018-01-04.

- ^ Chand M, Shukla AK. Novel Synthesis of Bicalutamide Drug Substance and their Impurities using Imidazolium Type of Ionic Liquid (报告). 2012. SSRN 2160199 . doi:10.2139/ssrn.2160199 .

- ^ Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Current aspects of antiandrogen therapy in women. Current Pharmaceutical Design. September 1999, 5 (9): 707–23 [2016-09-27]. PMID 10495361. doi:10.2174/1381612805666230111201150. (原始内容存档于2023-01-10).

Several trials demonstrated complete clearing of acne with flutamide [62,77]. Flutamide used in combination with an [oral contraceptive], at a dose of 500mg/d, flutamide caused a dramatic decrease (80%) in total acne, seborrhea and hair loss score after only 3 months of therapy [53]. When used as a monotherapy in lean and obese PCOS, it significantly improves the signs of hyperandrogenism, hirsutism and particularly acne [48]. [...] flutamide 500mg/d combined with an [oral contraceptive] caused an increase in cosmetically acceptable hair density, in sex of seven women suffering from diffuse androgenetic alopecia [53].

- ^ Denis LJ, Griffiths K, Kaisary AV, Murphy GP. Textbook of Prostate Cancer: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. 1999-03-01: 55,279–280. ISBN 978-1-85317-422-3. (原始内容存档于2016-06-03).

- ^ Elks J. The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 2014-11-14: 573–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. (原始内容存档于2016-05-15).

- ^ Furr BJ. Research on reproductive medicine in the pharmaceutical industry. Hum Fertil (Camb). 1998, 1 (1): 56–63. PMID 11844311. doi:10.1080/1464727982000198131.

- ^ Furr BJ. Casodex: preclinical studies and controversies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. June 1995, 761 (1): 79–96. Bibcode:1995NYASA.761...79F. PMID 7625752. S2CID 37242269. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb31371.x.

- ^ Cadilla R, Turnbull P. Selective androgen receptor modulators in drug discovery: medicinal chemistry and therapeutic potential. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006, 6 (3): 245–70 [2019-12-11]. PMID 16515480. doi:10.2174/156802606776173456. (原始内容存档于2020-08-18).

- ^ Engel J, Kleemann A, Kutscher B, Reichert D. Pharmaceutical Substances: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs 5th. Thieme. 2009: 153–154. ISBN 978-3-13-179275-4.

- ^ Furr BJ, Valcaccia B, Curry B, Woodburn JR, Chesterson G, Tucker H. ICI 176,334: a novel non-steroidal, peripherally selective antiandrogen. The Journal of Endocrinology. June 1987, 113 (3): R7–9. PMID 3625091. doi:10.1677/joe.0.113r007.

- ^ Bicalutamide. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). (原始内容存档于26 November 2016).

- ^ Morton IK, Hal JM. Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. 2012-12-06: 51–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. (原始内容存档于2016-05-14).

- ^ Ganellin CR, Triggle DJ. Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents. CRC Press. 1996-11-21: 570–. ISBN 978-0-412-46630-4. (原始内容存档于2016-05-07).

- ^ Ferraro MB, Orendt AM, Facelli JC. Parallel Genetic Algorithms for Crystal Structure Prediction: Successes and Failures in Predicting Bicalutamide Polymorphs. Huang D, Jo K, Lee H, Kang H, Bevilacqua V (编). Emerging Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications: 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computing, ICIC 2009 Ulsan, South Korea, September 16–19, 2009 Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5754. Springer. 2009-09-19: 120– [2016-09-27]. ISBN 978-3-642-04070-2. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04070-2_14. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ Dhas NL, Ige PP, Kudarha RR. Design, optimization and in-vitro study of folic acid conjugated-chitosan functionalized PLGA nanoparticle for delivery of bicalutamide in prostate cancer. Powder Technology. 2015, 283: 234–245. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2015.04.053.

- ^ Moul JW. Twenty years of controversy surrounding combined androgen blockade for advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. August 2009, 115 (15): 3376–8. PMID 19484788. S2CID 5670663. doi:10.1002/cncr.24393 .

- ^ Stuhan MA. Understanding Pharmacology for Pharmacy Technicians. ASHP. 2 April 2013: 268– [2016-11-05]. ISBN 978-1-58528-360-6. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ Allan GF, Sui Z. Therapeutic androgen receptor ligands. Nucl Recept Signal. 2003, 1: e009. PMC 1402218 . PMID 16604181. doi:10.1621/nrs.01009.

- ^ Annual Report and Form 20-F 2007 (PDF). AstraZeneca. [2024-05-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-03-06).

- ^ 118.0 118.1 Campbell T. Slowing Sales for Johnson & Johnson's Zytiga May Be Good News for Medivation. The Motley Fool. 2014-01-22 [2016-07-20]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-26).

[...] the most commonly prescribed treatment for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer: bicalutamide. That was sold as AstraZeneca's billion-dollar-a-year drug Casodex before losing patent protection in 2008. AstraZeneca still generates a few hundred million dollars in sales from Casodex, [...]

- ^ Actavis Generic Prostate Cancer Drug Bicalutamide First to Market in UK, Germany, France. Press Release. AstraZeneca, Actavis. 2008-07-10 [2024-05-09]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-28).

- ^ Hermkens PH, Kamp S, Lusher S, Veeneman GH. Non-steroidal steroid receptor modulators. IDrugs. July 2006, 9 (7): 488–94. PMID 16821162. doi:10.2174/0929867053764671.

- ^ Chang S, Bicalutamide BPCA Drug Use Review in the Pediatric Population (PDF), U.S. Department of Health and Human Service, 2010-03-10 [2016-07-20], (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-10-24)

- ^ Wang LG, Mencher SK, McCarron JP, Ferrari AC. The biological basis for the use of an anti-androgen and a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor in the treatment of recurrent prostate cancer: Case report and review. Oncology Reports. 2004, 11 (6): 1325–9. PMID 15138573. doi:10.3892/or.11.6.1325.

- ^ Tay MH, Kaufman DS, Regan MM, Leibowitz SB, George DJ, Febbo PG, Manola J, Smith MR, Kaplan ID, Kantoff PW, Oh WK. Finasteride and bicalutamide as primary hormonal therapy in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Annals of Oncology. 2004, 15 (6): 974–8. PMID 15151957. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh221 .

- ^ Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, Galbreath RW, Allen ZA, Kurko B. Efficacy of neoadjuvant bicalutamide and dutasteride as a cytoreductive regimen before prostate brachytherapy. Urology. 2006, 68 (1): 116–20. PMID 16844453. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.061.

- ^ Sartor O, Gomella LG, Gagnier P, Melich K, Dann R. Dutasteride and bicalutamide in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: the Therapy Assessed by Rising PSA (TARP) study rationale and design. The Canadian Journal of Urology. 2009, 16 (5): 4806–12. PMID 19796455.

- ^ Chu FM, Sartor O, Gomella L, Rudo T, Somerville MC, Hereghty B, Manyak MJ. A randomised, double-blind study comparing the addition of bicalutamide with or without dutasteride to GnRH analogue therapy in men with non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2015, 51 (12): 1555–69. PMID 26048455. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.028.

- ^ Gaudet M, Vigneault É, Foster W, Meyer F, Martin AG. Randomized non-inferiority trial of Bicalutamide and Dutasteride versus LHRH agonists for prostate volume reduction prior to I-125 permanent implant brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2016, 118 (1): 141–7. PMID 26702991. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.022.

- ^ Dijkstra S, Witjes WP, Roos EP, Vijverberg PL, Geboers AD, Bruins JL, Smits GA, Vergunst H, Mulders PF. The AVOCAT study: Bicalutamide monotherapy versus combined bicalutamide plus dutasteride therapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic carcinoma of the prostate-a long-term follow-up comparison and quality of life analysis. SpringerPlus. 2016, 5: 653. PMC 4870485 . PMID 27330919. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2280-8 .

- ^ Fujimura T, Takayama K, Takahashi S, Inoue S. Estrogen and Androgen Blockade for Advanced Prostate Cancer in the Era of Precision Medicine. Cancers. January 2018, 10 (2): 29. PMC 5836061 . PMID 29360794. doi:10.3390/cancers10020029 .

- ^ Ho TH, Nunez-Nateras R, Hou YX, Bryce AH, Northfelt DW, Dueck AC, et al. A Study of Combination Bicalutamide and Raloxifene for Patients With Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. April 2017, 15 (2): 196–202.e1. PMID 27771244. S2CID 19043552. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2016.08.026.

- ^ McCoy J, Wambier CG, Vano-Galvan S, Shapiro J, Sinclair R, Müller Ramos P, Washenik K, Andrade M, Herrera S, Goren A. Racial Variations in COVID-19 Deaths May Be Due to Androgen Receptor Genetic Variants Associated with Prostate Cancer and Androgenetic Alopecia. Are Anti-Androgens a Potential Treatment for COVID-19?. J Cosmet Dermatol. April 2020, 19 (7): 1542–1543. PMC 7267367 . PMID 32333494. doi:10.1111/jocd.13455 .

- ^ A Phase II Trial to Promote Recovery from COVID-19 with Endocrine Therapy. 2021-03-02 [2024-05-09]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-26).

延伸阅读

编辑- Bicalutamide. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2017 [2024-05-09]. PMID 31643303. NBK547970. (原始内容存档于2016-11-23) –通过NCBI Bookshelf.

- Blackledge GR. Clinical progress with a new antiandrogen, Casodex (bicalutamide). European Urology. 1996, 29 (Suppl 2): 96–104. PMID 8717470. doi:10.1159/000473847.

- Cockshott ID. Bicalutamide: clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2004, 43 (13): 855–78. PMID 15509184. S2CID 29912565. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00003.

- Fradet Y. Bicalutamide (Casodex) in the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. February 2004, 4 (1): 37–48. PMID 14748655. S2CID 34153031. doi:10.1586/14737140.4.1.37.

- Furr BJ. Casodex: preclinical studies and controversies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. June 1995, 761 (1): 79–96. Bibcode:1995NYASA.761...79F. PMID 7625752. S2CID 37242269. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb31371.x.

- Furr BJ, Tucker H. The preclinical development of bicalutamide: pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action. Urology. January 1996, 47 (1A Suppl): 13–25; discussion 29–32. PMID 8560673. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80003-3.

- Kolvenbag GJ, Blackledge GR. Worldwide activity and safety of bicalutamide: a summary review. Urology. January 1996, 47 (1A Suppl): 70–9; discussion 80–4. PMID 8560681. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(96)80012-4.

- Schellhammer PF, Davis JW. An evaluation of bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. Clinical Prostate Cancer. March 2004, 2 (4): 213–9. PMID 15072604. doi:10.3816/CGC.2004.n.002.

- Tucker H, Crook JW, Chesterson GJ. Nonsteroidal antiandrogens. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 3-substituted derivatives of 2-hydroxypropionanilides. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31 (5): 954–9. PMID 3361581. doi:10.1021/jm00400a011.

- Wellington K, Keam SJ. Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer. Drugs. 2006, 66 (6): 837–50. PMID 16706554. S2CID 46966712. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007.