美国人

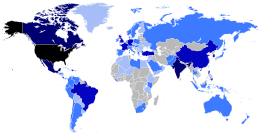

美国人(英语:Americans)[注 1],指的是美国公民。侨民或美国永久居民也可申请美国国籍。[39][40][41][42][43][44]美国是许多民族的家园。因此,美国的文化和法律并不把国籍等同于种族或民族,而是将其视作一种公民身份,也象征着对国家的效忠。[45][46][47]

| 美国人 Americans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 总人口 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 约3.314亿[1] (2020年美国人口普查)  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 分布地区 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 738,100–1,000,000[2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 316,350–1,000,000[4][5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2,694–700,000[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 220,000–600,000[7][8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 260,000[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 200,000[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 200,000[11][12] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 197,143(仅包含不在英国出生的)[13] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 120,000–158,000[14] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 120,000–130,000[15] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 111,529(仅包含美国公民)[16] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 110,000[17] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60,000[18] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60,000[19] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59,172-153,389[20][21] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56,276[22] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52,486[23] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50,000[24] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50,000[25] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45,000[26] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40,000[27] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37,000[28] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33,509[29] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30,000[30] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30,000[来源请求] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25,000[31] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25,000[32] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24,457[33] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22,082[34] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19,161[35] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19,000[36] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21,462[37] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 语言 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 主要是美国英语,此外还有西班牙语和其他语言 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 宗教信仰 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 主要是基督教(新教,天主教,和其他基督教派系) 犹太教、伊斯兰教和其他宗教[38] 无宗教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

概览

编辑大部分美国人并非原住民,而是移民和移民的后代。随着美国领地的不断扩张,夏威夷、波多黎各、关岛、美属萨摩亚、美属维尔京群岛以及北马里亚纳群岛的住民也陆续成为美国人。[48] [49] [40]

美国的主流文化主要源自西欧和北欧,但也受到了非裔美国人的影响。[50]随着西进运动的进行,路易斯安那的卡郡人和克里奥尔人、西南部的拉丁裔以及墨西哥人的文化也对美国文化产生了影响。19世纪末至20世纪初,来自南欧、东欧、亚洲、非洲和拉丁美洲的移民也影响了美国文化。在美国,各种文化一方面保持着自身的特征,一方面又相互融合,因此美国常被称为文化大熔炉或文化沙拉盘。[51]

种族和民族

编辑美国是一个多元文化主义国家。[55]美国普查局因统计需要将美国人划分为六个种族:白人、美国印第安人和阿拉斯加原住民、亚洲人、黑人或非洲裔美国人、夏威夷原住民和其他太平洋岛原住民,以及两个或两个以上种族的人。此外也可以选择“其他种族”。普查局还将美国人分为拉丁裔和非拉丁裔,而拉丁裔是美国最大的少数族裔。[56][57][58]

美国白人

编辑根据2010年美国人口普查,3.08亿美国人中有72.4%是白人。[59]其祖先是欧洲、中东和北非的原住民。[52]另有2.4%是白人与其他种族的混血儿,其中黑白混血儿最多。[59]拉丁裔白人占美国人口的9.4%,在加利福尼亚、得克萨斯、新墨西哥、内华达和夏威夷占多数。[60][61]非拉丁裔白人比例最高的州是缅因州。[62]此外,非白人在哥伦比亚特区和五个有常住人口的海外领土占多数。[52]

最早在美国大陆建立殖民据点的欧洲人是西班牙人,这段历史可以追溯到1565年。[63]马丁·德·阿圭列斯是第一个生于美洲大陆的欧洲裔,他生于1566年新西班牙总督辖区的圣奥古斯丁。[64]此外,西班牙人还于1521年在波多黎各建立了圣胡安市。弗吉尼亚·戴尔是第一个生于北美十三州的英格兰裔,她生于1587年的罗阿诺克殖民地。

根据2017年美国社区调查,德裔、爱尔兰裔、英格兰裔和意大利裔是美国的四大欧裔群体,占总人口的35.1%。[65]然而,英格兰裔和英国裔的人口被认为遭到严重低估。因为他们在美国居住的时间很长,一般只会说自己是美国人,而不会强调自己的祖先来自哪里。[注 3]这一现像在长期以英国裔为主的上南方尤其明显。[66][67][68][69][70][71]

在美国所有种族中,欧裔美国人的贫困率最低,受教育程度、家庭所得中位数和个人所得中位数位居第二。[72][73][74]

| 美国白人人口统计 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 族群 | 占美国人口百分比 | 估计人口 | 数据来源 | |

| 1 | 德裔 | 13.2% | 43,093,766 | [65] | |

| 2 | 爱尔兰裔 | 9.7% | 31,479,232 | [65] | |

| 3 | 英格兰裔 | 7.1% | 23,074,947 | [65] | |

| 4 | 美国人 | 6.1% | 20,024,830 | [65] | |

| 5 | 墨西哥裔 | 5.4% | 16,794,111 | [75] | |

| 6 | 意大利裔 | 5.1% | 16,650,674 | [65] | |

| 7 | 波兰裔 | 2.8% | 9,012,085 | [65] | |

| 8 | 法裔 (不包含巴斯克裔) 法裔加拿大美国人 |

2.4% 0.6% |

7,673,619 2,110,014 |

[65] | |

| 9 | 苏格兰裔 | 1.7% | 5,399,371 | [65] | |

| 10 | 挪威裔 | 1.3% | 4,295,981 | [65] | |

| 11 | 荷兰裔 | 1.2% | 3,906,193 | [65] | |

| 总计 | 美国白人 | 59.34% | 231,040,398 | [59] | |

| 来源:[76][77] 2010年美国人口普查和2017年美国社区调查 | |||||

中东和北非裔

编辑根据美国犹太人档案馆和阿拉伯裔美国人国家博物馆的资料,第一批中东人和北非人(即犹太人和柏柏尔人)在15世纪末至16世纪中期抵达美洲。[78][79][80]许多人是为了躲避西班牙宗教裁判所的迫害,还有一些人成为了美洲殖民者的奴隶。[81][82][83]阿拉伯裔美国人研究所指出,22个阿盟成员国中,每个国家都有人移民美国。[84]

自1909年以来,美国人口调查局一直将中东和北非人归为白人。随着时代的变迁,许多专家认为这个分类已经过时。2014年,在与中东和北非组织协商后,普查局宣布将为来自中东、北非和阿拉伯世界的人建立一个新的族群类别,称为MENA。[注 4][85]2018年1月,普查局宣布,2020年美国人口普查将不会单独统计中东和北非人。[86]

| 族群 | 2000年 | 2000年(占美国人口比例) | 2010年 | 2010年(占美国人口比例) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 阿拉伯裔 | 1,160,729 | 0.4125% | 1,697,570 | 0.5498% |

| 亚美尼亚裔 | 385,488 | 0.1370% | 474,559 | 0.1537% |

| 伊朗裔 | 338,266 | 0.1202% | 463,552 | 0.1501% |

| 犹太人 | 6,155,000 | 2.1810% | 6,543,820 | 2.1157% |

| 其他 | 529,289 | 0.185718% | 801,831 | 0.257771% |

| 总计 | 8,568,772 | 3.036418% | 9,981,332 | 3.227071% |

来源:2000[87]-2010年美国人口普查[88]曼德尔·博曼研究所和博曼犹太人数据库[89]

拉丁裔美国人

编辑根据2010年普查,拉丁裔美国人占美国人口的16.3%,是美国最大的少数族裔。[90][91]

| 美国拉丁裔人口统计[92][93] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 族群 | 占人口百分比 | 人口 | 来源 | |

| 1 | 墨西哥裔 | 10.29% | 31,798,258 | [93] | |

| 2 | 波多黎各裔 | 1.49% | 4,623,716 | [93] | |

| 3 | 古巴裔 | 0.57% | 1,785,547 | [93] | |

| 4 | 萨尔瓦多裔 | 0.53% | 1,648,968 | [93] | |

| 5 | 多米尼加裔 | 0.45% | 1,414,703 | [93] | |

| 6 | 危地马拉裔 | 0.33% | 1,044,209 | [93] | |

| 7 | 哥伦比亚裔 | 0.3% | 908,734 | [93] | |

| 8 | 西班牙裔 | 0.2% | 635,253 | [93] | |

| 9 | 洪都拉斯裔 | 0.2% | 633,401 | [93] | |

| 10 | 厄瓜多尔裔 | 0.1% | 564,631 | [93] | |

| 11 | 秘鲁裔 | 0.1% | 531,358 | [93] | |

| 其他 | 2.62% | 7,630,835 | |||

| 总计 | 16.34% | 50,477,594 | |||

| 2010年美国人口普查 | |||||

非裔美国人

编辑非裔美国人通常来自撒哈拉以南非洲和加勒比地区。[94][95]不过并非所有来自撒哈拉以南非洲的人都是黑人,许多佛得角裔、马达加斯加裔、阿非利卡人,以及来自东非和萨赫勒地区的居民并非黑人。[94]

根据2009年美国社区调查,全美共有38,093,725名非裔美国人,占总人口的12.4%。其中37,144,530名为非拉丁裔黑人,占总人口的12.1%。[96]根据2010年美国人口普查,非裔美国人(包括混血黑人)共有4200万,[95]占总人口的14%。[97]非裔美国人主要生活在美国南部(55%) 。与2000年相比,美国东北部与中西部的黑人数量有所下降。[97]

大部分非裔美国人的祖先都是来自西非的俘虏,他们被当做奴隶带到美国。[98]1619年,弗吉尼亚州的詹姆斯敦首次雇佣黑奴。英国人将这些奴隶视为契约劳工,工作满一定年数便可获得自由。随着时间的推移,这种做法逐渐被加勒比地区基于种族的奴隶制取代。[99]所有美国殖民地都有奴隶制,北方黑人通常是仆人,南方黑人通常是种植园劳工。[100]独立战争时期,一些黑人在大陆军或大陆海军中服役。[101][102]也有些黑人是保王党,在英军服役。[103]1804年,美国梅森-迪克森线以北的州废除了奴隶制,[104]而南方各州仍保留奴隶制。双方矛盾的激化最终导致了南北战争。最终,北方军获得胜利,宪法第十三条修正案获得通过,奴隶制正式废除。[105]美国重建时期结束后,非裔美国人首次在国会取得席位。[106]但他们仍然没有选举权,并依照吉姆·克劳法与白人强制隔离。[107]这种情况一直持续至1960年代的非裔美国人民权运动时期,在非裔美国人的持续抗争下,选举法案和1964年民权法案得到通过,种族间的权利不平等得到解决。[108]

根据2000年的普查数据,相较于非裔美国人这一身份,绝大多数非洲移民更认同自身的原生民族,仅有5%的非洲移民认为自己是非裔美国人。其中西非移民对非裔美国人的认同度最高(4%-9%),佛得角、东非和非洲南部的移民认同度最低(0%-4%)。[109]

| 非裔美国人人口统计[76][95] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 族群 | 百分比 占总人口 |

估计人口 | |

| 1 | 牙买加裔美国人 | 0.31% | 986,897 | |

| 2 | 海地裔美国人 | 0.28% | 873,003 | |

| 3 | 尼日利亚裔美国人 | 0.08% | 259,934 | |

| 4 | 特立尼达和多巴哥裔美国人 | 0.06% | 193,233 | |

| 5 | 加纳裔美国人 | 0.03% | 94,405 | |

| 6 | 巴巴多斯裔美国人 | 0.01% | 59,236 | |

| 撒哈拉以南非洲(总计) | 0.92% | 2,864,067 | ||

| 加勒比美国人(总计)(不含拉丁裔) | 0.85% | 2,633,149 | ||

| 非裔美国人(总计) | 13.6% | 42,020,743 | ||

| 2010年美国人口普查及2009–2011年美国社区调查 | ||||

亚裔美国人

编辑尽管早在美国独立战争之前就有亚裔生活在北美殖民地,[110][111]但大部分亚裔是从19世纪中后期开始才移民至美国的。[112]2010年,美国有1730万亚裔,占总人口的5.6%。[113][114]亚裔最多的州是加利福尼亚州,共有560万。[115]占比最高的州是夏威夷州,占比57%。[115]城市人口在亚裔当中占比很高,大洛杉矶地区、纽约都会区和旧金山湾区有大量亚裔。[116]

亚裔不是单一的族群,而是由许多国家的移民及其后裔组成的。包括中国大陆、台湾、日本、韩国、印度、巴基斯坦、菲律宾、越南、柬埔寨、老挝等。亚裔的收入和教育水平高于其他种族,而这一差距还在持续扩大。[117][118][119]

亚裔被称为“模范少数族裔”[120][121][122],也被称为“永远的外国人”。[123][124]

| 亚裔人口统计[113] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 族群 | 占人口百分比 | 人口 | |

| 1 | 华裔 | 1.2% | 3,797,379 | |

| 2 | 菲律宾裔 | 1.1% | 3,417,285 | |

| 3 | 印度裔 | 1.0% | 3,183,063 | |

| 4 | 越南裔 | 0.5% | 1,737,665 | |

| 5 | 韩裔 | 0.5% | 1,707,027 | |

| 6 | 日裔 | 0.4% | 1,304,599 | |

| 其他 | 0.9% | 2,799,448 | ||

| 总计 | 5.6% | 17,320,856 | ||

| 2010年美国人口普查 | ||||

美洲原住民

编辑根据2010年人口普查,美国有520万人(占总人口1.7%)有原住民血统,其中230万是混血。40.7%的原住民居住在美国西部。[125]其他种族也不同程度地含有原住民的基因,美国黑人平均含有0.8%的原住民基因,白人有0.18%,而拉丁裔则有18.0%。[126][127]

美洲原住民于45,000至10,000年前来到美洲大陆。[128]前哥伦布时期的原住民发展出了数百种不同文化。[129]随着哥伦布的到来[130],欧洲开始殖民美洲。从16世纪到19世纪,原住民不断减少。其中的原因包括欧洲人与原住民之间的战争和通婚[131][132],对原住民的奴役、强制迁移[133]和种族灭绝[134][135],还有欧洲人带来的流行病。[136]

| 美国的美洲原住民人口统计[125][137] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 部落 | 占总人口百分比 | 人口 | |

| 1 | 切罗基人 | 0.26% | 819,105 | |

| 2 | 纳瓦霍人 | 0.1% | 332,129 | |

| 3 | 乔克托族 | 0.06% | 195,764 | |

| 4 | 墨西哥原住民 | 0.05% | 175,494 | |

| 5 | 欧及布威族 | 0.05% | 170,742 | |

| 6 | 苏族 | 0.05% | 170,110 | |

| 其他 | 1.08% | 3,357,235 | ||

| 总计 | 1.69% | 5,220,579 | ||

| 2010年美国人口普查 | ||||

太平洋岛原住民

编辑根据2010年人口普查,美国有120万太平洋岛原住民,占总人口的0.4%,其中56%是混血,14%的人至少有一个学士学位,15.1%的人生活在贫困线以下。71%的人生活在美国西部,其中有52%生活在夏威夷州或加利福尼亚州,其他州的人口都不超过10万。火奴鲁鲁郡和洛杉矶郡是太平洋岛民的主要聚居地。[138][139]

| 美国太平洋岛原住民人口统计[139] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 族群 | 占人口百分比 | 人口 | |

| 1 | 夏威夷族 | 0.17% | 527,077 | |

| 2 | 萨摩亚裔 | 0.05% | 184,440 | |

| 3 | 查莫罗人 | 0.04% | 147,798 | |

| 4 | 汤加裔美国人 | 0.01% | 57,183 | |

| 其他 | 0.09% | 308,697 | ||

| 总计 | 0.39% | 1,225,195 | ||

| 2010年美国人口普查 | ||||

多种族美国人

编辑随着时代变迁,美国的多种族运动也逐渐壮大。[140]2008年,多种族美国人有700万,占总人口的2.3%;[114]而根据2010年的普查,这一数字增长到了9,009,073,占总人口的2.9%。其中黑白混血儿最常见,有1,834,212名,[141]第44任美国总统贝拉克·奥巴马就是其中一例。他的母亲是白人(有英格兰和爱尔兰血统),而父亲则是生于肯尼亚的卢欧族[142][143](但自我认同为非裔美国人)。[144][145]

| 多种族美国人数量[146] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 种族 | 占总人口百分比 | 人口 | |

| 1 | 白人与黑人 | 0.59 | 1,834,212 | |

| 2 | 其他 | 0.58 | 1,794,402 | |

| 3 | 白人与其他种族 | 0.56 | 1,740,924 | |

| 4 | 白人与亚裔 | 0.52 | 1,623,234 | |

| 5 | 白人与原住民 | 0.46 | 1,432,309 | |

| 6 | 黑人与其他种族 | 0.1 | 314,571 | |

| 7 | 黑人与原住民 | 0.08 | 269,421 | |

| 总计 | 2.9 | 9,009,073 | ||

| 2010年美国人口普查 | ||||

其他种族

编辑根据2010年美国人口普查,其他种族[注 5]是美国的第三大族群,有6.2%(19,107,368名)的美国人属于此类别。36.7%(18,503,103名)的拉丁裔是其他种族,[147]其中有不少是麦士蒂索人[注 6],此比例在墨西哥和中美洲社区中尤其高。但美国人口普查不统计麦士蒂索人。

国家化身

编辑山姆大叔是美国的国家化身,有时也特指美国政府。该词第一次使用是在1812年战争期间。他的形象通常是一位严厉的白人老人,头发花白,留着山羊胡,其衣着通常含有美国国旗的元素。

哥伦比亚是美国的女性化身。该词起初用来指代美洲,后因非裔美国诗人菲利斯·惠特利在美国独立战争期间的使用而广为人知。其后,包括西半球在内的许多地区都将哥伦比亚用作人物、地点、物体、机构和公司的名字。美国政府所在地哥伦比亚特区就是其中一个例子。

语言

编辑| 语言 | 人口百分比 | 使用者数量 |

|---|---|---|

| 英语 | 80.38% | 233,780,338 |

| 西班牙语 (不包括克里奥尔语和波多黎各) |

12.19% | 35,437,985 |

| 汉语 (包括现代标准汉语和粤语) |

0.88% | 2,567,779 |

| 他加禄语 | 0.53% | 1,542,118 |

| 越南语 | 0.44% | 1,292,448 |

| 法语 | 0.44% | 1,288,833 |

| 韩语 | 0.38% | 1,108,408 |

| 德语 | 0.38% | 1,107,869 |

| 印度斯坦语 (包括印地语和乌尔都语) |

0.32% | 942,794 |

| 其他语言 | 4.04% | 11,760,383 |

美国英语是美国事实上的国家语言。虽然联邦政府没有规定官方语言,但英语至少在28个州取得了官方语言的地位。也因此,一些美国人主张将英语作为美国的官方语言。[149]美国对入籍申请者的英语能力亦有要求。2007年,约有2.26亿美国人(占5岁及以上人口的80%)在家只说英语。西班牙语是美国的第二大语言,约有12%的人在家说西班牙语。[150][151]西班牙语也是波多黎各的官方语言。此外,新墨西哥州政府也使用西班牙语,而路易斯安那州政府亦使用法语,但两州均未规定官方语言。[152]加利福尼亚等州则要求某些政府文件(如法庭表格)必须有西班牙文版。[153]另外,根据夏威夷州法律,英语和夏威夷语都是其官方语言。[154]一些美国非合并属地对原住民语言也给予了官方认可。美属萨摩亚和关岛分别承认萨摩亚语和查莫罗语,而北马里亚纳群岛则承认加罗林语和查莫罗语。

宗教

编辑| 宗教 | 教徒占美国人口比例(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 基督教 | 70.6 | |

| 新教 | 46.5 | |

| 福音主义 | 25.4 | |

| 主流新教 | 14.7 | |

| 黑人教会 | 6.5 | |

| 天主教 | 20.8 | |

| 耶稣基督后期圣徒教会 | 1.6 | |

| 耶和华见证人 | 0.8 | |

| 东正教 | 0.5 | |

| 其他基督教 | 0.4 | |

| 非基督教信仰 | 5.9 | |

| 犹太教 | 1.9 | |

| 伊斯兰教 | 0.9 | |

| 佛教 | 0.7 | |

| 印度教 | 0.7 | |

| 其他非基督教 | 1.8 | |

| 无宗教 | 22.8 | |

| 无特定宗教 | 15.8 | |

| 不可知论 | 4.0 | |

| 无神论 | 3.1 | |

| 不知道或拒绝回答 | 0.6 | |

| 总计 | 100 | |

美国是世界上宗教最多元化的国家之一,不论是本土信仰还是外来信仰都能在美国蓬勃发展。[156]大多数美国人表示,宗教在他们的生活中扮演着“非常重要”的角色,这在发达国家中并不常见,但在美洲国家中却十分普遍。[157]美国是第一个禁止设立国教的国家,其宪法第一修正案禁止联邦政府制定任何法律来确立国教或禁止信教自由。[158]该法条是少数宗教团体和各州人民争取的结果,也受到了新教和理性主义的影响。美国最高法院解释道,该法条的设立是为了防止政府以公权力干涉宗教。此外,美国宪法第六条第三款规定:合众国政府之任何职位或公职,不得以任何宗教标准作为任职的必要条件。该法条以弗吉尼亚宗教自由法令为范本。[159]

美国拥有世界上最多的基督徒。[160]76%的美国人信仰基督教,其中大多信仰新教和天主教,他们分别占美国人口的48%和23%。[161]其他宗教包括佛教、印度教、伊斯兰教和犹太教,这些教徒占成年人口的4%至5%。[162][163][164]另有15%的成年人自认没有宗教信仰。[162]根据美国宗教认同调查,全美各地的宗教信仰差异很大:美国西部(无教堂带)有59%的人信神,而南部(圣经带)则有86%。[162][165]

此外,北美十三州中也有部分是由基督徒建立的,他们为了能够自由地信仰自己的宗教而来到北美。其中,马萨诸塞湾殖民地由英国清教徒建立,宾夕法尼亚省由英国和爱尔兰的贵格会教徒建立,马里兰省由英国和爱尔兰的天主教徒建立,弗吉尼亚殖民地由英国圣公宗教徒建立。

-

哥伦比亚特区的圣母无玷始胎国家朝圣地圣殿是美国最大的天主教堂

-

加州马里布的印度教神庙

文化

编辑美国地域宽广,人口众多,文化多样性高。保守主义与自由主义,科学与宗教在这里碰撞融合。美国人普遍崇尚个人主义,相信自由、平等与民主的价值,对言论自由与国家的政治制度十分重视。此外,美国人也比较喜欢冒险。

美国文化主要被西方文化所影响,但也受到了原住民、西非、东亚、波利尼西亚和拉丁美洲文化的影响。殖民时期对美国影响最大的是英国。通过殖民,英国向美洲大陆传播了他们的语言、法律与其他文化。[166]此外,以德国、[167]法国[168]和意大利[169]为代表的其他一些欧洲国家也对美国文化产生了重要影响。

美国的本土文化也有着强大的影响力。美国的本土节日、体育运动、军事传统[170]以及艺术和娱乐方面的创新带给国民强烈的民族自豪感。[171]美国在许多方面都有自己独特的社会和文化特征,如方言、音乐、艺术、社会习惯、饮食和民俗。[172]

对外移民

编辑许多国家或地区都有来自美国的移民,包括阿根廷、澳大利亚、巴西、加拿大、智利、中国、哥斯达黎加、法国、德国、香港、印度、日本、墨西哥、新西兰、巴基斯坦、菲律宾、韩国、阿联酋和英国。截至2016年[update],约有900万美国公民生活在海外。[173]

参见

编辑注释

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ Census Bureau's 2020 Population Count. 美国人口普查. [2021-04-26]. The 2020 census is as of April 1, 2020.

- ^ People live in Mexico, INEGI, 2010. [2012-03-31]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-04).

- ^ Smith, Dr. Claire M. These are our Numbers: Civilian Americans Overseas and Voter Turnout (PDF). OVF Research Newsletter. Overseas Vote Foundation. August 2010 [2012-12-11]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-10-24).

Previous research indicates that the number of U.S. Americans living in Mexico is around 1 million, with 600,000 of those living in Mexico City.

- ^ Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories - 20% sample data. Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. 2010-06-10 [2013-02-17]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-11).

Ethnic origins Americans Total responses 316,350

- ^ Barrie McKenna. Tax amnesty offered to Americans in Canada. The Globe and Mail (Ottawa). 2012-06-27 [2012-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-01).

There are roughly a million Americans in Canada – many with little or no ties to the United States.

- ^ Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Table 1. Total migrant stock at mid-year by origin and by major area, region, country, or a area of destination, 1990-2017 (报告). United Nations. December 2017 [2019-06-29]. International Migration. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2007-02-14).

HV1731 2,694

United Nations Population Division. Origins and Destinations of the World's Migrants, 1990-2017 (报告). Pew Research Center: Global Attitudes & Trends. 2018-02-28 [2019-06-29]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-30).United States <10,000

Gottipati, Sruthi. Expats Flock to India Seeking Jobs, Excitement. The New York Times. 2012-02-08 [2019-03-20]. (原始内容存档于2019-03-21).While 35,973 U.S. citizens (not including those eligible for special visas available for Americans of Indian origin) registered in 2008, 41,938 did so the following year, according to the latest figures available with the Ministry of Home Affairs.

White House. The United States and India — Prosperity Through Partnership. whitehouse.gov. 2017-06-26 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-02-27) –通过National Archives.Today, nearly 4 million Indian-Americans reside in the United States and over 700,000 U.S. citizens live in India. Last year, the United States Government issued nearly one million visas to Indian citizens, and facilitated 1.7 million visits by Indian citizens to the United States.

- ^ Evan S. Medeiros; Keith Crane; Eric Heginbotham; Norman D. Levin; Julia F. Lowell. Pacific Currents: The Responses of U.S. Allies and Security Partners in East Asia to Chinaâ€TMs Rise. Rand Corporation. 2008-11-07: 115 [2021-09-06]. ISBN 978-0-8330-4708-3. (原始内容存档于2020-07-25).

An estimated 4 million Filipino-Americans, most of whom are U.S. citizens or dual citizens, live in the United States, and over 250,000 U.S. citizens live in the Philippines.

New U.S. ambassador to PH aims to 'strengthen' ties. CNN Philippines (Metro Manila). 2016-12-02 [2017-03-20]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-21).According to his figures, there are about 4 million Filipino-Americans residing in the U.S., and 250,000 Americans living and working in the Philippines.

Lozada, Aaron. New U.S. envoy: Relationship with PH 'most important'. ABS-CBN News (Manila). 2016-12-02 [2017-03-20]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-21).According to Kim, the special relations between the U.S. and the Philippines is evident in the "four million Filipino-Americans who are residing in the United States and 250,000 Americans living and working in the Philippines."

International Business Publications, USA. Philippines Business Law Handbook: Strategic Information and Laws. Int'l Business Publications. 2013-08-01: 29 [2021-09-06]. ISBN 978-1-4387-7078-9. (原始内容存档于2017-03-22).An estimated 600,000 Americans visit the Philippines each year, while an estimated 300,000 reside in-country.

Kapoor, Kanupriya; Dela Cruz, Enrico. Americans in Philippines jittery as Duterte rails against United States. Reuters (奥隆阿波). 2016-10-17 [2018-04-20]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-21).About four million people of Philippine ancestry live in the United States, one of its largest minorities, and about 220,000 Americans, many of them military veterans, live in the Philippines. An additional 650,000 visit each year, according to U.S. State Department figures.

FACT SHEET: United States-Philippines Bilateral Relations. U.S. Embassy in the Philippines. United States Department of State. 2014-04-28 [2018-04-20]. (原始内容存档于2017-02-17).Around 350,000 Americans reside in the Philippines, and approximately 600,000 U.S. citizens visit the country each year.

- ^ Cooper, Matthew. Why the Philippines Is America's Forgotten Colony. National Journal. 2013-11-15 [2015-01-28]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

c. At the same time, person-to-person contacts are widespread: Some 600,000 Americans live in the Philippines and there are 3 million Filipino-Americans, many of whom are devoting themselves to typhoon relief.

- ^ US Embassy in Brazil (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) US Embassy in Brazil. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Americans in France. 美国驻法国大使馆. United States Department of State. [2015-04-26]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-18).

Today, although no official figure is available it is estimated that over 150,000 American citizens reside in France, making France one of the top 10 destinations for American expatriates.

- ^ Daphna Berman. Need an appointment at the U.S. Embassy? Get on line!. Haaretz. 2008-01-23 [2012-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-24).

According to estimates, some 200,000 American citizens live in Israel and the Palestinian territories.

- ^ Michele Chabin. In vitro babies denied U.S. citizenship. USA Today (Jerusalem). 2012-03-19 [2012-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-29).

Most of the 200,000 U.S. citizens in Israel have dual citizenship, and fertility treatments are common because they are free.

- ^ Simon Rogers. The UK's foreign-born population: see where people live and where they're from. The Guardian. 2011-05-26 [2013-02-17]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-01).

County of birth and county of nationality. United States of America 197 143

- ^ U.S. Citizen Services. Embassy of the United States Seoul, Korea. United States Department of State. [2012-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2012-11-30).

This website is updated daily and should be your primary resource when applying for a passport, Consular Report of Birth Abroad, notarization, or any of the other services we offer to the estimated 120,000 U.S. citizens traveling, living, and working in Korea.

North Korea propaganda video depicts invasion of South Korea, US hostage taking. Advertiser. Agence France-Presse. 2013-03-22 [2013-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-12).According to official immigration figures, South Korea has an American population of more than 130,000 civilians and 28,000 troops.

- ^ Background Note: Costa Rica. Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. United States Department of State. 2012-04-09 [2012-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2021-07-07).

Over 130,000 private American citizens, including many retirees, reside in the country and more than 700,000 American citizens visit Costa Rica annually.

Bloom, Laura Begley. More Americans are fleeing to cheap faraway places. New York Post. 2018-07-31 [2020-02-19]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-20).Approximately 120,000 citizens live in this stable country, many as retirees, according to the State Department.

- ^ publisher. Pressemitteilungen - Ausländische Bevölkerung - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). www.destatis.de. [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2017-11-24).

- ^ Calum Macleod. A guide to success in China, by Americans who live there. 2005-11-18 [2020-05-24]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-07).

- ^ Colombia (03/28/13). United States Department of State. [2014-02-27]. (原始内容存档于2013-04-20).

Based on Colombian statistics, an estimated 60,000 U.S. citizens reside in Colombia and 280,000 U.S. citizens travel, study and do business in Colombia each year.

- ^ Hong Kong (10/11/11). Previous Editions of Hong Kong Background Note. United States Department of State. 2011-10-11 [2012-12-11]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-02).

There are some 1,400 U.S. firms, including 817 regional operations (288 regional headquarters and 529 regional offices), and over 60,000 American residents in Hong Kong.

- ^ 令和元年末現在における在留外国人数について (Excel). Immigration Services Agency of Japan. [2021-04-08]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-10).

- ^ 在日米軍の施設・区域内外居住(人数・基準) (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2008-02-22 [2021-04-08]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-07-07).

- ^ ibid, Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex – Australia. [2014-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-08).

- ^ Gishkori, Zahid. Karachi has witnessed 43% decrease in target killing: Nisar. The Express Tribune. 2015-07-30 [2017-08-03]. (原始内容存档于2021-06-27).

52,486 Americans... are residing in [Pakistan], the interior minister added.

- ^ Kelly Carter. High cost of living crush Americans' dreams of Italian living. USA Today (Positano, Italy). 2005-05-17 [2012-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-01).

Nearly 50,000 Americans lived in Italy at the end of 2003, according to Italy's immigration office.

- ^ UAE´s population – by nationality. BQ Magazine. 2015-04-12 [2015-06-13]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-11).

- ^ McKinley Jr.; James C. For 45,000 Americans in Haiti, the Quake Was 'a Nightmare That's Not Ending'. The New York Times. 2010-01-17 [2015-02-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-03).

- ^ SAUDI-U.S. TRADE. Commerce Office. Embassy of Saudi Arabia in Washington, D.C.. [2012-02-14]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-13).

Furthermore, there are approximately 40,000 Americans living and working in the Kingdom.

- ^ Argentina (03/12/12). Previous Editions of Argentina Background Note. United States Department of State. 2012-03-12 [2012-12-24]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-29).

The Embassy's Consular Section monitors the welfare and whereabouts of some 37,000 U.S. citizen residents of Argentina and more than 500,000 U.S. tourists each year.

- ^ Statistics Norway – Persons with immigrant background by immigration category and country background. January 1, 2010. [2014-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2010-10-28).

- ^ Bahamas, The (01/25/12). Previous Editions of Panama Background Note. United States Department of State. 2012-01-25 [2012-12-29]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-27).

The countries share ethnic and cultural ties, especially in education, and The Bahamas is home to approximately 30,000 American residents.

- ^ Kate King. U.S. family: Get us out of Lebanon. CNN. 2006-07-18 [2012-02-14]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-06).

About 350 of the estimated 25,000 American citizens in Lebanon had been flown to Cyprus from the U.S. Embassy in Beirut by nightfall Tuesday, Maura Harty, the assistant secretary of state for consular affairs, told reporters.

- ^ Panama (03/09). Previous Editions of Panama Background Note. United States Department of State. March 2009 [2012-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-29).

About 25,000 American citizens reside in Panama, many retirees from the Panama Canal Commission and individuals who hold dual nationality.

- ^ IX Censo Nacional de Poblacion y Vivenda 2010 (PDF): 101. [2015-07-23]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-09-27).

- ^ Foreign population by sex, country of nationality and age (up to 85 and above).. Instituto Natcional de Estadistica. 2007-01-01 [2018-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-12-13) (西班牙语).

Both genders 22,082

- ^ S. Vedoya; V. Rivera. Gobierno cifra en más de un millón el número de inmigrantes que están en Chile. Latercera. 2018-04-04 [2018-04-20]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-06) (西班牙语).

- ^ El Salvador (01/10). United States Department of State. [2014-04-11]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-13).

More than 19,000 American citizens live and work full-time in El Salvador

- ^ North Americans: Facts and figures. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. [2012-03-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-07-31).

- ^ Luis Lug; Sandra Stencel; John Green; Gregory Smith; Dan Cox; Allison Pond; Tracy Miller; Elixabeth Podrebarac; Michelle Ralston. U.S. Religious Landscape Survey (PDF). Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research Center. February 2008 [2012-02-12]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-07-05).

- ^ 美国法典第8编 § 第1401节; 美国法典第8编 § 第1408节; 美国法典第8编 § 第1452节; see also

- Ricketts v. Attorney General, 897 F.3d 491. Third Circuit: 494 n.3. 2018-07-30 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

While all citizens are nationals, not all nationals are citizens.

- Tuaua v. United States, 788 F.3d 300. D.C. Circuit: 302. 2015-06-05 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Fernandez v. Keisler, 502 F.3d 337. Fourth Circuit: 341. 2007-09-26 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-30).

All citizens of the United States are nationals, but some nationals are not citizens.

- Miller v. Albright, 523 U.S. 420. U.S. Supreme Court: 467 n.2. 1998-04-22 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- United States v. Morin, 80 F.3d 124. Fourth Circuit: 126. 1996-04-05 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Ricketts v. Attorney General, 897 F.3d 491. Third Circuit: 494 n.3. 2018-07-30 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ 40.0 40.1 *U.S. nationals born in American Samoa sue for citizenship. NBC News. Associated Press. 2018-03-28 [2018-10-01]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-28).

- Mendoza, Moises. How a weird law gives one group American nationality but not citizenship. 国际公众电台 (PRI). 2014-10-11 [2018-08-24]. (原始内容存档于2018-08-25).

- ^ *Cheneau v. Garland, No. 15-70636. Ninth Circuit: 3. 2021-05-18 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Findley v. Barr, No. 17-2530. Second Circuit: 2. 2020-10-14 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Allen v. Barr, No. 18-3028. Second Circuit: 4. 2020-01-03 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Espichan v. Attorney General, 945 F.3d 794. Third Circuit: 796. 2019-12-27 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Tineo v. Attorney General, 937 F.3d 200. Third Circuit: 218. 2019-09-04 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Khalid v. Sessions, 904 F.3d 129. Second Circuit: 131. 2018-09-13 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- Belleri v. United States, 712 F.3d 543. Eleventh Circuit: 545. 2013-03-14 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-30).

- Anderson v. Holder, 673 F.3d 1089. Ninth Circuit: 1092. 2012-03-12 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- In re Petition of Tubig, 559 F. Supp. 2. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California: 3. 1981-10-07 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ See

- 8 CFR 1003.2(c)(3)(vi) (about filing a "motion to reopen" Removal proceedings with the Board of Immigration Appeals "based on specific allegations, supported by evidence, that the respondent is a United States citizen or national");

- 22 CFR 51.1 ("U.S. non-citizen national means a person on whom U.S. nationality, but not U.S. citizenship, has been conferred at birth under 8 U.S.C. 1408, or under 判例法 or Refugee Act, and who has not subsequently lost such non-citizen nationality.").

- ^ Petersen, William; Novak, Michael; Gleason, Philip. Concepts of Ethnicity. Harvard University Press. 1982: 62 [2013-02-01]. ISBN 9780674157262. (原始内容存档于2021-03-14).

...from Thomas Paine's plea in 1783...to Henry Clay's remark in 1815... "It is hard for us to believe ... how conscious these early Americans were of the job of developing American character out of the regional and generational polaritities and contradictions of a nation of immigrants and migrants." ... To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be of any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political ideology centered on the abstract ideals of liberty, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American.

- ^ Foreign nationals. Federal Election Commission. 2017-06-23 [2021-02-18]. (原始内容存档于2020-08-21).

- ^ *Fernandez v. Keisler, 502 F.3d 337. Fourth Circuit: 341. 2007-09-26 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-30).

The INA defines 'national of the United States' as '(A) a citizen of the United States, or (B) a person who, though not a citizen of the United States, owes permanent allegiance to the United States.'

- Robertson-Dewar v. Mukasey, 599 F. Supp. 2d 772. U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas: 779 n.3. 2009-02-25 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-30).

The [INA] defines naturalization as 'conferring of nationality of a state upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever.'

- Robertson-Dewar v. Mukasey, 599 F. Supp. 2d 772. U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas: 779 n.3. 2009-02-25 [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-30).

- ^ Permanent Allegiance Law and Legal Definition. definitions.uslegal.com. [2021-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-25).

- ^ Christine Barbour; Gerald C Wright. Keeping the Republic: Power and Citizenship in American Politics, 6th Edition The Essentials. CQ Press. 2013-01-15: 31–33 [2015-01-06]. ISBN 978-1-4522-4003-9. (原始内容存档于2016-04-24).

Who Is An American? Native-born and naturalized citizens

Shklar, Judith N. American Citizenship: The Quest for Inclusion. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Harvard University Press. 1991: 3–4 [2012-12-17]. ISBN 9780674022164. (原始内容存档于2016-06-03).

Slotkin, Richard. Unit Pride: Ethnic Platoons and the Myths of American Nationality. American Literary History (Oxford University Press). 2001, 13 (3): 469–498 [2012-12-17]. S2CID 143996198. doi:10.1093/alh/13.3.469. (原始内容存档于2019-11-08).But it also expresses a myth of American nationality that remains vital in our political and cultural life: the idealized self-image of a multiethnic, multiracial democracy, hospitable to differences but united by a common sense of national belonging.

Eder, Klaus; Giesen, Bernhard. European Citizenship: Between National Legacies and Postnational Projects. Oxford University Press. 2001: 25–26 [2013-02-01]. ISBN 9780199241200. (原始内容存档于2021-01-20).In inter-state relations, the American nation state presents its members as a monistic political body-despite ethnic and national groups in the interior.

Petersen, William; Novak, Michael; Gleason, Philip. Concepts of Ethnicity. Harvard University Press. 1982: 62 [2013-02-01]. ISBN 9780674157262. (原始内容存档于2021-03-14).To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be of any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political ideology centered on the abstract ideals of liberty, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American.

Charles Hirschman; Philip Kasinitz; Josh Dewind. The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience. Russell Sage Foundation. 1999-11-04: 300. ISBN 978-1-61044-289-3.

David Halle. America's Working Man: Work, Home, and Politics Among Blue Collar Property Owners. University of Chicago Press. 1987-07-15: 233 [2021-09-06]. ISBN 978-0-226-31366-5. (原始内容存档于2016-12-20).The first, and central, way involves the view that Americans are all those persons born within the boundaries of the United States or admitted to citizenship by the government.

- ^ Lifshey, Adam. Subversions of the American Century: Filipino Literature in Spanish and the Transpacific Transformation of the United States. University of Michigan Press. 2015: 119 [2021-09-08]. ISBN 978-0-472-05293-6. (原始内容存档于2020-07-25).

the status of Filipinos in the Philippines as American nationals existed from 1900 to 1946

Rick Baldoz. The Third Asiatic Invasion: Empire and Migration in Filipino America, 1898-1946. NYU Press. 2011-02-28: 174 [2021-09-08]. ISBN 978-0-8147-9109-7. (原始内容存档于2020-07-25).Recalling earlier debates surrounding Filipinos' naturalization status in the United States, he pointed out that U.S. courts had definitively recognized that Filipinos were American "nationals" and not "aliens."

8 FAM 302.5 Special Citizenship Provisions Regarding the Philippines. Foreign Affairs Manual. United States Department of State. 2020-05-15 [2020-06-09]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-19). - ^ U.S. Census Bureau. Foreign-Born Population Frequently asked Questions (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) viewed January 19, 2015. The U.S. Census Bureau uses the terms native and native born to refer to anyone born in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or the U.S. Virgin Islands.

- ^ Holloway, Joseph E. (2005). Africanisms in American Culture, 2d ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 18–38. ISBN 0-253-34479-4. Johnson, Fern L. (1999). Speaking Culturally: Language Diversity in the United States. Thousand Oaks, California, London, and New Delhi: Sage, p. 116. ISBN 0-8039-5912-5.

- ^ Adams, J.Q., and Pearlie Strother-Adams (2001). Dealing with Diversity. Chicago: Kendall/Hunt. ISBN 0-7872-8145-X.

- ^ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Karen R. Humes; Nicholas A. Jones; Roberto R. Ramirez. Percentage of Population and Percent Change by Race: 2010 and 2020 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. March 2011 [September 20, 2021]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-08-13).

- ^ Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race: 2010 and 2020 (PDF). 2020 Census Summary. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [September 20, 2021]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-08-13).

- ^ Population by Hispanic or Latino Origin: 2010 and 2020 (PDF). 2020 Census. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [September 20, 2021]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-08-13).

- ^ Our Diverse Population: Race and Hispanic Origin, 2000 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. [2008-04-24]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2004-07-15).

- ^ Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Office of Management and Budget. [2008-05-05]. (原始内容存档于2009-03-15).

- ^ Grieco, Elizabeth M; Rachel C. Cassidy. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2000 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. [2015-01-02]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-05-01).

- ^ U.S. Census website. 2008 Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. [2010-02-28]. (原始内容存档于1996-12-27).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Lindsay Hixson; Bradford B. Hepler; Myoung Ouk Kim. The White Population: 2010 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. September 2011 [2012-11-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-09-30).

- ^ U.S. whites will soon be the minority in number, but not power – Baltimore Sun. The Baltimore Sun. [2018-01-21]. (原始内容存档于2017-08-08).

- ^ Minority population surging in Texas. NBC News. Associated Press. 2005-08-18 [2009-12-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-31).

- ^ Bernstein, Robert. Most Children Younger Than Age 1 are Minorities, Census Bureau Reports. United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2012-05-17 [2012-12-16]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-18).

- ^ A Spanish Expedition Established St. Augustine in Florida. Library of Congress. [2009-03-27]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-10).

- ^ D. H. Figueredo. Latino Chronology: Chronologies of the American Mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2007: 35 [2021-09-18]. ISBN 978-0-313-34154-0. (原始内容存档于2020-08-11).

- ^ 65.00 65.01 65.02 65.03 65.04 65.05 65.06 65.07 65.08 65.09 65.10 Selected Social Characteristics in the United States (DP02): 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. [2018-11-20]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-14).

- ^ Ethnic Landscapes of America (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) - By John A. Cross

- ^ Census and you: monthly news from the U.S. Bureau... Volume 28, Issue 2 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) - By United States. Bureau of the Census

- ^ Sharing the Dream: White Males in a Multicultural America (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) By Dominic J. Pulera.

- ^ Reynolds Farley, 'The New Census Question about Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?', Demography, Vol. 28, No. 3 (August 1991), pp. 414, 421.

- ^ Stanley Lieberson and Lawrence Santi, 'The Use of Nativity Data to Estimate Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns', Social Science Research, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1985), pp. 44-6.

- ^ Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters, 'Ethnic Groups in Flux: The Changing Ethnic Responses of American Whites', Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 487, No. 79 (September 1986), pp. 82-86.

- ^ Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2004 (PDF). [2021-09-18]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-01-23).

- ^ Median household income newsbrief, US Census Bureau 2005. [2006-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2006-09-03).

- ^ US Census Bureau, Personal income for Asian Americans, age 25+, 2006. [2006-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2006-09-29).

- ^ Sharon R. Ennis; Merarys Ríos-Vargas; Nora G. Albert. The Hispanic Population: 2010 (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau: 14 (Table 6). May 2011 [2011-07-11]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-01-27).

- ^ 76.0 76.1 B04006, People Reporting Ancestry. 2009-2011 American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau. [2012-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-12).

- ^ Table 52. Population by Selected Ancestry Group and Region: 2009 (PDF). 2009 American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau. January 2011 [2012-11-20]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-10-23).

- ^ "History Crash Course #55: Jews and the Founding of America" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Spiro, Rabbi Ken. Aish.com. Published December 8, 2001. Accessed December 12, 2015. "The first Jews arrived in America with Columbus in 1492, and we also know that Jews newly-converted to Christianity were among the first Spaniards to arrive in Mexico with Conquistador Hernando Cortez in 1519."

- ^ "Arab Americans: An Integral Part of American Society" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Arab American National Museum. Published 2009. Accessed December 12, 2015. "Zammouri, the first Arab American...traveled over 6,000 miles between 1528 and 1536, trekking across the American Southwest."

- ^ "The American Jewish Experience through the Nineteenth Century: Immigration and Acculturation" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Golden, Jonathan, and Jonathan D. Sarna. National Humanities Center. Brandeis University. Accessed December 12, 2015.

- ^ Netanyahu, Benzion.The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain. New York: Random House, 1995. Hardcover. 1390 pages. p. 1085.

- ^ "Conversos & Crypto-Jews" 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期December 22, 2015,. City of Albuquerque. Accessed December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Timeline in American Jewish History" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) American Jewish Archives. Accessed December 12, 2015.

- ^ Arab American Institute – Texas (PDF). Arab American Institute. [2015-12-12]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-02-07).

- ^ Public Comments to NCT Federal Register Notice (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau; Department of Commerce. [2015-12-13]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-07-26).

- ^ Wang, Hansi Lo. No Middle Eastern Or North African Category On 2020 Census, Bureau Says. National Public Radio. 2018-01-29 [2018-06-09]. (原始内容存档于2022-02-21).

- ^ Table 1. First, Second, and Total Responses to the Ancestry Question by Detailed Ancestry Code: 2000 (XLS). U.S. Census Bureau. [2010-12-02]. (原始内容存档于2020-05-09).

- ^ Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported: 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. United States Census Bureau. [2012-11-30]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-12).

- ^ Ira Sheskin; Arnold Dashefsky. Jewish Population in the United States, 2010 (PDF). Mandell L. Berman Institute North American Jewish Data Bank, Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life, University of Connecticut. Brandeis University. 2010 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-10-25).

|issue=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

tthqvu的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Humes, Karen R.; Jones, Nicholas A.; Ramirez, Roberto R. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010 (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. [2011-03-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-04-29).

"Hispanic or Latino" refers to a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race.

- ^ Sharon R. Ennis; Merarys Ríos-Vargas; Nora G. Albert. The Hispanic Population: 2010 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. May 2011 [2012-09-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-01-27).

- ^ 93.00 93.01 93.02 93.03 93.04 93.05 93.06 93.07 93.08 93.09 93.10 93.11 2010 Census Shows Nation's Hispanic Population Grew Four Times Faster Than Total U.S. Population. United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2011-05-26 [2012-09-09]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-08).

- ^ 94.0 94.1 Race, Ethnicity, and Language data - Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement (PDF). Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. [May 10, 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-11-29).

- ^ 95.0 95.1 95.2 Sonya Tastogi; Tallese D. Johnson; Elizabeth M. Hoeffel; Malcolm P. Drewery, Jr. The Black Population: 2010 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. September 2011 [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-01-31).

- ^ United States – ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2009 Archive.is的存档,存档日期February 11, 2020,. Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ 97.0 97.1 2010 Census Shows Black Population has Highest Concentration in the South. United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. September 29, 2011 [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档于September 15, 2012).

- ^ The size and regional distribution of the black population. Lewis Mumford Center. [October 1, 2007]. (原始内容存档于October 12, 2007).

- ^ New World Exploration and English Ambition. The Terrible Transformation. PBS. [September 11, 2011]. (原始内容存档于June 14, 2007).

- ^ Gomez, Michael A. Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. University of North Carolina Press. 1998: 384 [2021-11-27]. ISBN 9780807846940. (原始内容存档于2021-11-27).

- ^ Liberty! (Documentary) Episode II:Blows Must Decide: 1774-1776. ©1997 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. ISBN 1-4157-0217-9

- ^ Foner, Philip Sheldon. Blacks in the American Revolution. Volume 55 of Contributions in American history. Greenwood Press. 1976: 70 [2021-11-27]. ISBN 9780837189468. (原始内容存档于2021-11-27).

- ^ Black Loyalists. Black Presence. The National Archives. [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-25).

- ^ Nicholas Boston; Jennifer Hallam. Freedom & Emancipation. Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Public Broadcasting Service. 2004 [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-25).

- ^ 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. ourdocuments.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档于2022-01-06).

- ^ The Fifteenth Amendment in Flesh and Blood. Office of the Clerk. United States House of Representatives. [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档于December 11, 2012).

- ^ Walter, Hazen. American Black History. Lorenz Educational Press. 2004: 37 [September 11, 2012]. ISBN 9780787706036. (原始内容存档于2021-11-27).

- ^ The Prize. We Shall Overcome. National Park Service. [September 11, 2012]. (原始内容存档于2021-06-06).

- ^ Kusow, AM. African Immigrants in the United States: Implications for Affirmative Action. Iowa State University. [May 10, 2016]. (原始内容存档于2016-06-10).

- ^ The Journey from Gold Mountain: The Asian American Experience (PDF). Japanese American Citizens League: 3. 2006 [2016-11-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-04-12).

- ^ California Declares Filipino American History Month. San Francisco Business Times. 2009-09-10 [2011-02-14]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Hune, Shirley; Takeuchi, David T.; Andresen, Third; Hong, Seunghye; Kang, Julie; Redmond, Mavae'Aho; Yeo, Jeomja. Asian Americans in Washington State: Closing Their Hidden Achievement Gaps (PDF). Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs. State of Washington. April 2009 [2012-02-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-11-03).

- ^ 113.0 113.1 2010 United States Census statistics (PDF). [2021-09-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-04-29).

- ^ 114.0 114.1 B02001. RACE – Universe: TOTAL POPULATION. 2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. 美国普查局. [2010-02-28]. (原始内容存档于1996-12-27).

- ^ 115.0 115.1 Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2011. Facts for Features. U.S. Census Bureau. 2011-12-07 [2012-01-04]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-08).

- ^ Shan Li. Asian Americans had higher poverty rate than whites in 2011, study says. Los Angeles Times. 2013-05-03 [2013-05-06]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-06).

In 2011, for example, nearly a third of Asians in the U.S. lived in the metropolitan regions around Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York.

Selected Population Profile in the United States. U.S. Census. U.S. Department of Commerce. [2011-06-25]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-12). - ^ Meizhu Lui; Barbara Robles; Betsy Leondar-Wright; Rose Brewer; Rebecca Adamson. The Color of Wealth. The New Press. 2006.

- ^ US Census Bureau report on educational attainment in the United States, 2003 (PDF). [2006-07-31]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-10-02).

- ^ The American Community-Asians: 2004 (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. February 2007 [2007-09-05]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2007-09-26).

- ^ Chou, Rosalind; Joe R. Feagin. The myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Paradigm Publishers. 2008: x [2011-02-09]. ISBN 978-1-59451-586-6. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Tamar Lewin. Report Takes Aim at 'Model Minority' Stereotype of Asian-American Students. 纽约时报. 2008-06-10 [2012-02-09]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Tojo Thatchenkery. Asian Americans Under the Model Minority Gaze. International Association of Business Disciplines National Conference. modelminority.com. 2000-03-31 [2012-02-26]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-18).

- ^ Lien, Pei-te; Mary Margaret Conway; Janelle Wong. The politics of Asian Americans: diversity and community. Psychology Press. 2004: 7 [2012-02-09]. ISBN 978-0-415-93465-7. (原始内容存档于2021-03-26).

In addition, because of their perceived racial difference, rapid and continuous immigration from Asia, and on going detente with communist regimes in Asia, Asian Americans are construed as "perpetual foreigners" who cannot or will not adapt to the language, customs, religions, and politics of the American mainstream.

- ^ Wu, Frank H. Yellow: race in America beyond black and white. Basic Books. 2003: 79 [2012-02-09]. ISBN 978-0-465-00640-3.

asian americans perpetual foreigners.

- ^ 125.0 125.1 Tina Norris; Paula L. Vines; Elizabeth M. Hoeffel. The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. January 2012 [2012-09-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-05-05).

- ^ Bryc, Katarzyna; Durand, Eric Y.; Macpherson, J. Michael; Reich, David; Mountain, Joanna L. The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. The American Journal of Human Genetics. January 2015, 96 (1): 37–53. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 4289685 . PMID 25529636. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010.

- ^ Carl Zimmer. White? Black? A Murky Distinction Grows Still Murkier. The New York Times. 2014-12-24 [2018-10-21]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-15).

The researchers found that European-Americans had genomes that were on average 98.6 percent European, .19 percent African, and .18 Native American.

- ^ Axelrod, Alan. The Complete Idiot's Guide to American History. Complete Idiot's Guide to. Penguin. 2003: 4 [2012-09-09]. ISBN 9780028644646. (原始内容存档于2021-08-13).

- ^ Magoc, Chris J. Chronology of Americans and the Environment. ABC-CLIO. 2011: 1 [2012-09-09]. ISBN 9781598844115. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ Columbus, Christopher; de las Casas, Bartolomé; Dunn, Oliver; Kelley, James Edward. de las Casas, Bartolomé; Dunn, Oliver , 编. The Diario of Christopher Columbus's First Voyage to America, 1492-1493. Volume 70 of American Exploration and Travel Series. University of Oklahoma Press. 1991: 491 [2012-09-09]. ISBN 9780806123844. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Woods Weierman, Karen. One Nation, One Blood: Interracial Marriage In American Fiction, Scandal, and Law, 1820-1870. University of Massachusetts Press. 2005: 44 [2012-09-09]. ISBN 9781558494831. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ Mann, Kaarin. Interracial Marriage In Early America: Motivation and the Colonial Project (PDF). Michigan Journal of History (University of Michigan). 2007, (Fall) [2012-09-08]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-05-15).

- ^ R. David Edmunds. Native American Displacement Amid U.S. Expansion. KERA. Public Broadcasting Service. 2006-03-14 [2012-09-09]. (原始内容存档于2019-11-02).

- ^ Thornton, Russell. American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Volume 186 of Civilization of the American Indian Series. University of Oklahoma Press. 1987: 49 [2012-09-09]. ISBN 9780806122205.

genocide warfare europeans american indians.

- ^ Kessel, William B.; Wooster, Robert. Encyclopedia Of Native American Wars And Warfare. Facts on File library of American History. Infobase Publishing. 2005: 398 [2012-09-09]. ISBN 9780816033379. (原始内容存档于2021-09-03).

- ^ Bianchine, Peter J.; Russo, Thomas A. The Role of Epidemic Infectious Diseases in the Discovery of America. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings (OceanSide Publications, Inc). 1992, 13 (5): 225–232. PMID 1483570. doi:10.2500/108854192778817040.

- ^ American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month: November 2011. United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2011-11-01 [2012-09-09]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-06).

- ^ Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2011. United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2011-04-29 [2012-09-11]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-08).

- ^ 139.0 139.1 引用错误:没有为名为

2010CensusNHOPI的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Jon M. Spencer. The New Colored People: The Mixed-Race Movement in America. NYU Press. August 2000 [2021-09-27]. ISBN 978-0-8147-8072-5. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

Loretta I. Winters; Herman L. DeBose. New Faces in a Changing America: Multiracial Identity in the 21st Century. SAGE. 2003 [2021-09-27]. ISBN 978-0-7619-2300-8. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12). - ^ Karen R. Humes; Nicholas A. Jones; Roberto R. Ramirez. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010 (PDF). 2010 Census Briefs. United States Census Bureau. March 2011 [2013-02-22]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-04-29).

- ^ Ewen MacAskill; Nicholas Watt. Obama looks forward to rediscovering his Irish roots on European tour. The Guardian (London). 2011-05-20 [2011-08-03]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Mason, Jeff. Obama visits family roots in Ireland. Reuters. 2011-05-23 [2011-08-03]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Oscar Avila. Obama's census-form choice: 'Black'. Los Angeles Times. 2010-04-04 [2013-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-24).

- ^ Sam Roberts; Peter Baker. Asked to Declare His Race, Obama Checks 'Black'. The New York Times. 2010-04-02 [2013-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Nocholas A. Jones; Jungmiwka Bullock. The Two or More Races Population: 2010 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. September 2012 [2014-11-18]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-02-06).

- ^ Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010 (PDF). [2021-09-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-04-29).

- ^ United States. 美国现代语言学会. [2013-09-02]. (原始内容存档于2007-12-01).

- ^ Feder, Jody. English as the Official Language of the United States—Legal Background and Analysis of Legislation in the 110th Congress (PDF). Ilw.com (Congressional Research Service). 2007-01-25 [2007-06-19]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-06-22).

- ^ Table 53—Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2007 (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States 2010. U.S. Census Bureau. [2009-09-21]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-03-27).

- ^ Foreign Language Enrollments in United States Institutions of Higher Learning (PDF). MLA. Fall 2002 [2006-10-16]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于1999-11-27).

- ^ Dicker, Susan J. Languages in America: A Pluralist View. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. 2003: 216, 220–25. ISBN 1-85359-651-5.

- ^ California Code of Civil Procedure, Section 412.20(6). Legislative Counsel, State of California. [2007-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2010-07-22). California Judicial Council Forms. Judicial Council, State of California. [2007-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2011-06-24).

- ^ The Constitution of the State of Hawaii, Article XV, Section 4. Hawaii Legislative Reference Bureau. 1978-11-07 [2007-06-19]. (原始内容存档于2007-07-05).

- ^ America's Changing Religious Landscape. The Pew Forum. 2015-05-12 [2015-05-12]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-07).

- ^ Eck, Diana. A New Religious America: the World's Most Religiously Diverse Nation. HarperOne. 2002: 432. ISBN 978-0-06-062159-9.

- ^ U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion. Pew Global Attitudes Project. [2007-01-01]. (原始内容存档于2007-02-08).

- ^ Feldman, Noah (2005). Divided by God. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, pg. 10 ("For the first time in recorded history, they designed a government with no established religion at all.")

- ^ Marsden, George M. 1990. Religion and American Culture. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, pp.45–46.

- ^ ANALYSIS. Global Christianity. Pewforum.org. 2011-12-19 [2012-08-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-12-26).

- ^ Newport, Frank. Five Key Findings on Religion in the U.S.. Gallup. 2016-12-23 [2018-04-05]. (原始内容存档于2017-09-12) (美国英语).

- ^ 162.0 162.1 162.2 Barry A. Kosmin and Ariela Keysar. American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) 2008 (PDF). Hartford, Connecticut, US: Trinity College. 2009 [2009-04-01]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-01-22).

- ^ CIA Fact Book. CIA World Fact Book. 2002 [2007-12-30]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-21).

- ^ Religious Composition of the U.S. (PDF). U.S. Religious Landscape Survey. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2007 [2009-05-09]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2009-05-06).

- ^ Newport, Frank. Belief in God Far Lower in Western U.S.. 盖洛普. 2008-07-28 [2010-09-04]. (原始内容存档于2010-08-28).

- ^ Carlos E. Cortés. Multicultural America: A Multimedia Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. 2013-09-03: 220 [2021-09-20]. ISBN 978-1-4522-7626-7. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

The dominance of English and Anglo values in U.S. culture is evident in the country's major institutions, demonstrating the melting pot model.

- ^ Kirschbaum, Erik. The eradication of German culture in the United States, 1917-1918. H.-D. Heinz. 1986: 155 [2021-09-20]. ISBN 3-88099-617-2. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ Peter J. Parish. Reader's Guide to American History. Taylor & Francis. January 1997: 276 [2021-09-20]. ISBN 978-1-884964-22-0. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

However, France was second only to Britain in its influence upon the formation of American politics and culture.

- ^ Marilyn J. Coleman; Lawrence H. Ganong. The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. 2014-09-16: 775 [2021-09-20]. ISBN 978-1-4522-8615-0. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

As the communities grew and prospered, Italian food, entertainment, and music influenced American life and culture.

- ^ M. D. R. Evans; Jonathan Kelley. Religion, Morality and Public Policy in International Perspective, 1984-2002. Federation Press. January 2004: 302 [2021-09-20]. ISBN 978-1-86287-451-0. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12).

- ^ America tops in national pride survey finds. NBC News. Associated Press. 2006-06-27 [2014-10-22]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-23).

Elizabeth Theiss-Morse. Who Counts as an American?: The Boundaries of National Identity. Cambridge University Press. 2009-07-27: 133 [2021-09-20]. ISBN 978-1-139-48891-4. (原始内容存档于2021-11-12). - ^ Thompson, William, and Joseph Hickey (2005). Society in Focus. Boston: Pearson. ISBN 0-205-41365-X.

- ^ CA by the Numbers (PDF). (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-06-16).