醋酸环丙孕酮

醋酸环丙孕酮(cyproterone acetate,CPA),商品名有:色普龙、Androcur、安得卡等,是一种合成甾体抗雄激素、黄体制剂、抗促性腺激素。[1] 因其阻止内源雄激素与其受体结合以及抑制雄激素生物合成的抗雄作用,此药主要用于雄激素相关病况的治疗。[2] 有时也会使用CPA的孕激素样作用,例如达英–35(英语:Diane-35)这种复合口服避孕药就是此药和炔雌醇复配而成。[3]

| |

| |

| 临床数据 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Androcur、Cyprostat、Siterone、色普龙、安得卡等 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex详细消费者药物信息 |

| 怀孕分级 |

|

| 给药途径 | 口服给药, 肌肉注射 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | 100% |

| 血浆蛋白结合率 | 96% |

| 药物代谢 | 肝脏 |

| 生物半衰期 | 40小时 |

| 排泄途径 | 60%胆,33%肾 |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 427-51-0 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.409 |

| 化学信息 | |

| 化学式 | C24H29ClO4 |

| 摩尔质量 | 416.94 g/mol |

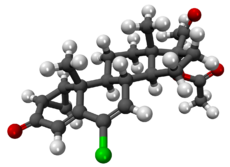

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

此条目可参照英语维基百科相应条目来扩充。 |

医疗用途

编辑CPA自1964年来就作为抗雄药剂使用,且是第一个用于临床的抗雄药。[4]此药在欧洲广泛使用,在加拿大、墨西哥等国家亦有使用。 由于对肝毒性的担忧,美国食品药品监督管理局并未批准此药,于是在美国使用醋酸甲羟孕酮取而代之。[5]CPA已被批准用于乳腺癌、 性早熟、与雄激素相关的皮肤病(如粉刺、脂溢性皮炎、雄激素性脱发),以及降低性罪犯的性冲动。[6]CPA与炔雌醇复方(有时称作co-cyprindiol)自1997年来也作为避孕药出售。[4]

CPA的其他适应症有良性前列腺增生症、阴茎异常勃起、性欲亢进、性偏离、潮热、女性雄激素过剩等。此外,CPA也广泛用于跨性别女性的性别肯定激素治疗(GAHT),美国由于未批准使用此药,一般则会使用螺内酯,一种具有抗雄作用的利尿剂。[7]

观察

编辑副作用

编辑女性化

编辑CPA的抗雄及抗促性腺激素作用在男性中直接造成的副作用有身体去雄性化、雌性化、乳房发育、乳房疼痛、乳溢症、性功能障碍(包括性欲减退和勃起功能障碍)、生精障碍和可逆转的不育。[4]在前列腺癌治疗中,CPA被男性患者称为能造成如手术阉割一般“严重”的性欲和勃起功能减退。[11]

抑郁

编辑现已发现CPA在男女中皆与抑郁率升高相关。[12]有报告称使用此药治疗多毛症(剂量25–100 mg)的女性中,可能有多达20–30%显示抑郁症状。[13][14]同时,也有研究发现大约20%的服用Dianette牌口服避孕药(只含2 mg CPA)的女性发生抑郁。[15],和接受更具选择性的GnRH类似物(一般不认为有显著抑郁风险,持续雌激素补充的话)治疗的跨性别女性相比,使用CPA作为GAHT的抗雄成分的患者也有高得多的出现抑郁症状的风险,且此风险与CPA关联。[16]CPA的抑郁作用可能与其糖皮质激素、抗雄激素、和/或抗促性腺激素作用有关,毕竟糖皮质激素、抗雄激素(对男性来说)以及GnRH类似物都和抑郁有关联。[17][18][19][20]CPA造成的维生素B12缺乏症也有可能是一个很重要的因素。[15]由于抑郁的副作用,在将CPA用于有抑郁症病史的患者时应特别小心,特别是当抑郁病史严重之时。[21]

血栓

编辑当单独使用时,CPA对凝血因子并没有表现出什么显著作用。然而在口服避孕药之类的情况下与炔雌醇联用时,便会提升发生深静脉血栓的风险。[22]服用含有CPA的避孕药的女性和不服用的女性相比,血栓形成的概率提升六到七倍,与服用含左炔诺孕酮避孕药的女性比则为两倍。[23]

肝毒性

编辑CPA的最严重的潜在副作用为其肝毒性。因此,服用CPA的患者,尤其是高剂量服用者(每日超过50–100 mg甚至200–300 mg),应该持续监视肝功能测试结果。[24]CPA的毒性取决于剂量,口服避孕药中2 mg那么低的剂量并没有显现出多少风险。[25]

脑膜瘤

编辑在罕见的情况下,高剂量(至少 25 mg/d)的CPA疗法与脑膜瘤的发生及恶化有关。此现象未见于低剂量的避孕药用途。[26][27]因此,脑膜瘤或脑膜瘤病史为使用CPA的一个禁忌。[21]

杂项

编辑联合雌激素使用高剂量的CPA在跨性别女性中和强烈(高达400倍)的高催乳素血症有关。[28]对于同一群体,单独雌激素则只与少数单一的催乳素瘤有关。[28]

由于对于雌激素生产的抑制,长期高剂量使用CPA而不伴随雌激素可引发骨质酥松症,对两性皆然。[29]

CPA也和妊娠纹生成有关,可能是由其糖皮质激素活性和/或其造成的皮肤干燥导致。[30]

现已发现高剂量(至少 50–100 mg/d)服用CPA会导致维生素B12缺乏症。[31][32] 在维生素B12缺乏症引发的多种症状中,由于单胺类神经递质耗尽引发的焦虑、应激性、疲倦较值得注意,[33][34]此外也有证据提示此症可能与CPA治疗中常见的神经—精神(neuropsychiatric)不良反应有关。[15]因此,建议在大剂量CPA质量中监测血清维生素B12含量并适时补充。[31][32]

戒断

编辑对CPA的突然戒断可能有害。Schering AG的说明书建议逐步降低剂量,每隔几周降低一次,每次减少的每日用量不超过50 mg。对戒断主要的担忧来自CPA对肾上腺的影响。由于其糖皮质激素作用,高剂量的CPA可能会降低ACTH,从而在突然戒断时导致肾上腺皮质功能不全。此外,CPA虽然降低性腺的雄激素分泌,却能提升肾上腺的雄激素产生量,有时会甚至导致总体睾酮含量提升。[35]因此,突然停止使用CPA可能导致意外的雄激素效果。[来源请求]之所以有这个担忧是因为雄激素(特别是二氢睾酮)抑制肾上腺功能,进一步降低皮质类固醇生成。[36]

肾上腺皮质功能不全

编辑有报道称醋酸环丙孕酮治疗中导致肾上腺功能抑制及促肾上腺皮质激素(ACTH)回应减弱的报告。这会导致肾上腺皮质功能不全,从而在停药时可能出现低皮质醇和醛固酮,以及较弱的ACTH反应。低醛固酮可能会导致低钠血症和高钾血症。服用醋酸环丙孕酮的患者应持续监测皮质醇和电解质情况,并在出现高钾血症时降低高钾含量食物的进食量,或是停止服药。

抗雄戒断综合征

编辑一些前列腺癌细胞会对醋酸环丙孕酮表现出一种截然不同的现象——这些细胞的雄激素受体发生突变,于是和平常情况下被醋酸环丙孕酮抑制不同,这些受体能被其激活。在这样的病例中,停止服用醋酸环丙孕酮反而可能减缓癌症生长。[37]

药理

编辑活性概要

编辑已知醋酸环丙孕酮存在以下药理学活性:

- 雄激素受体(AR)受体拮抗剂/极弱部分激动剂[38]

- 孕酮受体(PR)激动剂(Kd = 15 nM; IC50 = 79 nM)[38][39]

- 糖皮质激素受体(GR)拮抗剂(Kd = 45 nM; IC50 = 360 nM)[39]

- 21-羟化酶、3β-羟基类固醇脱氢酶(3β-HSD)、17α-羟化酶、17,20-裂合酶抑制剂[40]

- 孕烷 X 受体(PXR)激动剂(因而调控 CYP3A4、P-糖蛋白)[41][42]

醋酸环丙孕酮的孕激素和抗雄激素作用等强,[43]为17α-羟基黄体酮一族中最强的黄体激素。其强度为的醋酸羟孕酮的1200倍、醋酸甲羟孕酮的12倍、醋酸氯地孕酮的三倍。[43]17α-羟基黄体酮一族的孕激素极其强效,而醋酸环丙孕酮更是已知最强的孕激素,在生物检定法中有1000倍于孕酮的强度。[44]还有文献称CPA是迄今为止“最强力的”抗雄激素。[44]

CPA也可能对5α还原酶有轻微的抑制作用,不过目前的证据是稀少而互相矛盾。[45][46][47]与非那雄胺(一种既定的5α还原酶抑制剂)合用时,CPA对脱发的疗效远高于单用CPA时的情况——这提示要是CPA真的对5α还原酶有直接抑制作用,也不会多么突出。[48][49]

CPA对雌激素受体(ER)或盐皮质激素受体(MR)没有什么亲和力。[来源请求]

CPA还会非选择性地和μ-、δ-、κ-阿片样肽受体结合,不过与其其它活性相比弱得多—(抑制 [3H]二丙诺啡结合的 IC50 = 1.62 ± 0.33 µM)。[50]研究提示CPA激活阿片样肽受体的能力也许可以解释其高剂量下镇静的副作用,以及其治疗丛集性头痛的功能。[50]

抗雄活性

编辑醋酸环丙孕酮是一种较强的雄激素受体(AR)竞争性拮抗剂。[38]CPA可以直接阻碍内源性雄激素(如睾酮 (T)、双氢睾酮 (DHT))结合、激活雄激素受体,从而阻止其在体内产生雄激素作用。然而和螺内酯一样,醋酸环丙孕酮、醋酸氯地孕酮、醋酸甲羟孕酮这样的甾体抗雄激素并非单纯的雄激素受体拮抗剂,而是一种很弱的部分激动剂。[38][51][52][53]临床上,醋酸环丙孕酮基本上只展现出其抗雄激素的一面——CPA在受体处替换掉本来可以与之结合的那些效能的雄激素(T、DHT等),因此其净效应一般都是降低雄激素的生理活性。由于在雄激素受体处CPA仍有较弱的效能,CPA不能像氟他胺这样的AR沉默拮抗剂完全去除雄激素活性,总是会在一定程度上维持这种活性。

醋酸环丙孕酮激活雄激素受体的能力尽管很弱,也还是足以在没有其他雄激素的情况下促进对雄激素敏感的癌症——例如前列腺癌——生长(使用氟他胺一同治疗可以防止)。[51][52]因此,醋酸环丙孕酮在治疗这种癌症时可能不如非甾体抗雄药中的某些沉默拮抗剂有效。除了氟他胺之外,比卡鲁胺和恩杂鲁胺也属于AR沉默拮抗剂。[38][54]

间接雌激素活性

编辑由于CPA并不与雌激素受体(ER)结合,此药基本不具备雌激素活性(无论直接还是间接),甚至可能因为其抗促性腺激素活性在剂量足够时表现出抗雌作用。不过由于雄激素总体上会抵抗乳房雌激素的作用,单独使用CPA可以在男性中通过抗雄激素活性造成类似于雌激素的乳房女性化效果。无论如何,醋酸环丙孕酮的这种副作用在发生率和严重程度上都远低于非甾体抗雄药的程度。非甾体抗雄药不会降低(甚至会提高)雌激素水平。[55][56]

孕激素

编辑CPA是一种极强的孕激素;[57]之前也提到过, 其是目前已知最强效的孕激素。[44]与低剂量炔雌醇相结合作为激素避孕药,每日只需2 mg醋酸环丙孕酮即可有效。[57][58]

由于其孕激素作用,醋酸环丙孕酮可以大幅增加催乳素分泌、诱导雌性普通猕猴乳腺发育。[59]相应地,研究表明CPA和雌激素配合长期用药能使所有的跨性别女性的乳腺小叶完全发育。[60][61][62]在两位实验对象中观察到了类似妊娠的乳腺增生。[62]同一个研究还发现男性摄护腺癌症患者在服用接受不带孕激素活性的抗雄药物且不服用雌激素时,其乳腺只会稍有不完全发育。[60]因此,上述研究的作者认为跨性别女性要得到类似女性的(包括乳腺小叶在内)完全发育的胸部的话,需要同时接受孕激素和雌激素作用。[60][61]同时研究者还注意到手术去势后停止使用醋酸环丙孕酮会导致乳腺发育状态还原,说明保持发育后的结构需要持续使用孕激素治疗。[60]

醋酸环丙孕酮的孕激素作用致使其同时具有抗促性腺激素作用。[38][57]

抗促性腺激素

编辑CPA有强抗促性腺激素作用,[38]能够抑制人类由促性腺激素释放激素(GnRH)诱发分泌的促性腺激素过程,[63]因而显著降低血浆中黄体生成素(LH)和促卵泡激素(FSH)的浓度。由此也使孕酮(P4)、雄烯二酮、睾酮、二氢睾酮、雌二醇(E2)浓度显著降低;性激素结合球蛋白(SHBG)和催乳素含量则会上升。[64][65][66][67][68]CPA的抗促性腺激素活性由孕酮受体过激活诱发,[11][38][57]不过CPA的甾体酶抑制作用可能参与了其降低性类固醇水平的作用。[69]

其他活性

编辑糖皮质激素

编辑由于下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴(HPA)的负反馈作用,施用强的松和地塞米松等外源性糖皮质激素会抑制脑下垂体分泌促肾上腺皮质激素,从而抑制肾上腺分泌皮质醇,导致肾上腺抑制和萎缩。此时停止施用糖皮质激素会导致一过性的肾上腺功能不全。CPA同样能够稍微降低ACTH、皮质醇水平,诱发肾上腺萎缩,且在停药后也会造成人类和动物肾上腺功能不全,说明其也具有一些糖皮质激素作用。[70][71][72][73][74][75]矛盾的是,CPA在体外是糖皮质激素受体(GR)拮抗剂,[39][76][77]且能够通过抑制3β-羟基类固醇脱氢酶和21-羟化酶抑制肾上腺生产皮质醇和皮质酮,[71][78][79][80]因而表现出抗糖皮质激素活性。这个矛盾或许可以通过分析醋酸环丙孕酮的活性代谢产物解开:CPA的一些代谢产物,例如15β-羟基醋酸环丙孕酮(人类中的血清浓度为CPA原药两倍[81]),[82]是糖皮质激素激动剂。[83]由此可以假设这些产物总体的糖皮质激素活性盖过了CPA本身的抗糖皮质激素活性。环丙孕酮及其醋酸酯CPA通过各自的代谢产物都表现出糖皮质激素活性。基于小鼠研究,CPA的糖皮质激素活性强度大约为强的松的1/5。[84]

即使不少研究都显示醋酸环丙孕酮会显著造成皮质醇和ACTH相应降低,也有些研究报告即使剂量很高也没有这种效果。[83][85][86][87][88]

醋酸甲地孕酮、醋酸甲羟孕酮、醋酸氯地孕酮、类固醇黄体素和醋酸环丙孕酮的一些结构似体都有类似地糖皮质激素作用,因此都可能在停药时造成肾上腺功能不全。[89][90]

药物代谢

编辑CPA的亲脂性使其药物代谢动力学特性复杂许多。虽然对于CPA的平均生物半衰期一般估计为40小时左右,这个时长主要却是反映其在脂肪细胞中的累积过程。从血液中清除CPA的过程相比起来快上很多;脂肪中的储量可能受食物摄入影响。因此,建议按每日分2–3次,或者使用长效注射剂给药。

一部分摄入体内的CPA通过水解,代谢为环丙孕酮和乙酸。[91]不过,和其他类固醇酯不同,CPA并不会被大量水解;其药理活性实际上很多都来自于其原始形式:[24]醋酸环丙孕酮的抗雄活性大约为环丙孕酮三倍,[92]此外环丙孕酮本身完全不带孕激素活性。[44]

CPA由CYP3A4代谢,生成活性代谢产物醋酸15β-羟基环丙孕酮。此产物保留了CPA的抗雄活性,孕激素活性则有下降。[81][93][94]因此,与抑制CYP3A4的药物一同给药可提升醋酸环丙孕酮的孕激素活性。

吸收

编辑醋酸环丙孕酮的口服生物利用率被报告为100%。[95]然而,有说法称醋酸环丙孕酮通过消化道吸收较差,所以应该在进食后服用,能提升吸收效率。[96]

分布

编辑代谢

编辑排泄

编辑历史

编辑CPA于1960年代早期发现;1962年,Schering AG员工鲁道夫·维歇特和身在柏林的F·纽曼申请了一个“黄体激素制剂”的专利(美国专利第3,234,093号)。专利通过后一年的1966年,纽曼就发表了CPA在大鼠中抗雄作用的证据;此外还报告了CPA对脑有“有组织的效果”。[97]同年,瑞典隆德的一组研究人员发表研究,展示CPA对于雄性胎鼠有导致泌尿生殖系统畸形的能力。[98]从此,全世界都开始在动物实验中使用CPA研究抗雄激素影响性分化的程度和方式。

在1970年对于醋酸环丙孕酮进行了最早的人类实验——在口服给药后测量血浆中的药物浓度、精子生产速率[99],还有在女性中测量头发生长速度。1972年,精神科医师开始在“性变态”患者上使用这种药物[100]。1970年代中叶,螺内酯这类的不带或带有较弱孕激素作用的抗雄药开始出现。在亮丙瑞林开发出来之前,醋酸环丙孕酮是仅有的几种治疗性早熟的药物。

社会与文化

编辑命名

编辑“cyproterone acetate”为醋酸环丙孕酮的INN、USAN、BAN、JAN命名。此物质也可称为1,2α-亚甲基-6-氯-δ6-17α-乙酰氧基黄体酮。

醋酸环丙孕酮与炔雌醇的复方制剂的商品在全球大部分地方名为“达英-35”(Diane-35),在英国名为 Dianette,在德国名为 Bella Hexal,在瑞典名为 Diane,在智利名为 Dixi-35。[3]

参见

编辑外部链接

编辑引用

编辑- ^ Neumann F, Töpert M. Pharmacology of antiandrogens. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. November 1986, 25 (5B): 885–95. PMID 2949114. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(86)90320-1.

- ^ Jonathan S. Berek. Berek & Novak's Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007: 1085 [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-0-7817-6805-4. (原始内容存档于2020-02-27).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer. Combined Estrogen-progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. 2007: 437. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sarah H. Wakelin. Systemic Drug Treatment in Dermatology: A Handbook. CRC Press. 1 June 2002: 32 [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-1-84076-013-2. (原始内容存档于2020-07-27).

- ^ Dr Marius Duker; Dr Marijke Malsch. Incapacitation: Trends and New Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. 28 January 2013: 77 [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-1-4094-7151-6. (原始内容存档于2021-02-16).

- ^ Mario Maggi. Hormonal Therapy for Male Sexual Dysfunction. John Wiley & Sons. 17 November 2011: 104 [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-1-119-96380-6. (原始内容存档于2014-07-28).

- ^ J. Larry Jameson; David M. de Kretser; John C. Marshall; Leslie J. De Groot. Endocrinology Adult and Pediatric: Reproductive Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. 7 May 2013 [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-0-323-22152-8. (原始内容存档于2014-07-25).

- ^ Judith L. Rapoport. Obsessive-compulsive Disorder in Children and Adolescents. American Psychiatric Pub. 1 January 1989: 229–231. ISBN 978-0-88048-282-0.

- ^ Kellner M. Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010, 12 (2): 187–97. PMC 3181958 . PMID 20623923.

- ^ Juan José López Ibor; Carmen Leal Cercós; Carlos Carbonell Masiá. Images of Spanish Psychiatry. Editorial Glosa, S.L. 2004: 376–. ISBN 978-84-7429-200-8.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Iversen, P.; Melezinek, I.; Schmidt, A. Nonsteroidal antiandrogens: a therapeutic option for patients with advanced prostate cancer who wish to retain sexual interest and function. BJU International. 2001, 87 (1): 47–56. ISSN 1464-4096. PMID 11121992. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00988.x.

- ^ Ulrike Blume-Peytavi; David A. Whiting; Ralph M. Trüeb. Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. 26 June 2008: 181–. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7.

- ^ James Barrett. Transsexual and Other Disorders of Gender Identity: A Practical Guide to Management. Radcliffe Publishing. 2007: 174 [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-1-85775-719-4. (原始内容存档于2020-07-27).

- ^ Barth, J. H.; Cherry, C. A.; Wojnarowska, F.; Dawber, R. P. R. Cyproterone acetate for severe hirsutism:results of a double-blind dose-ranging study. Clinical Endocrinology. 1991, 35 (1): 5–10. ISSN 0300-0664. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb03489.x.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Rushton, D. H. Nutritional factors and hair loss. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2002, 27 (5): 396–404. ISSN 0307-6938. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01076.x.

- ^ Seal, L. J.; Franklin, S.; Richards, C.; Shishkareva, A.; Sinclaire, C.; Barrett, J. Predictive Markers for Mammoplasty and a Comparison of Side Effect Profiles in Transwomen Taking Various Hormonal Regimens. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012, 97 (12): 4422–4428. ISSN 0021-972X. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2030.

- ^ Boccardo, Francesco. Hormone therapy of prostate cancer: is there a role for antiandrogen monotherapy?. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2000, 35 (2): 121–132. ISSN 1040-8428. doi:10.1016/S1040-8428(00)00051-2.

- ^ Clive Peedell. Concise Clinical Oncology. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2005: 81–. ISBN 0-7506-8836-X.

- ^ Damber, Jan-Erik. Endocrine therapy for prostate cancer. Acta Oncologica. 2005, 44 (6): 605–609. ISSN 0284-186X. doi:10.1080/02841860510029743.

- ^ Robert G. Lahita. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Academic Press. 9 June 2004: 797– [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-0-08-047454-0. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Sarah H. Wakelin; Howard I. Maibach; Clive B. Archer. Handbook of Systemic Drug Treatment in Dermatology, Second Edition. CRC Press. 21 May 2015: 34–. ISBN 978-1-4822-2286-9.

- ^ Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick H. Risk of venous thromboembolism with cyproterone or levonorgestrel contraceptives. Lancet. 2001, 358 (9291): 1427–9. PMID 11705493. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06522-9.

- ^ Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, Skjeldestad FE, Løkkegaard E; Nielsen, L. H.; Skovlund, C. W.; Skjeldestad, F. E.; Lokkegaard, E. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses. BMJ. 2011, 343: 1–15. PMC 3202015 . PMID 22027398. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6423.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 Berlex Canada, Inc. Cyproterone Acetate Tablets and Injections Product Monographs (revised version) (PDF). 2003-02-10. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2006-09-24).

- ^ Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin, Volume 23, Number 1. February 2004. (原始内容存档于2006-09-04).

- ^ Meningeal Neoplasms—Advances in Research and Treatment: 2012 Edition: ScholarlyBrief. ScholarlyEditions. 26 December 2012: 99–. ISBN 978-1-4816-0002-6.

- ^ J. Larry Jameson; Leslie J. De Groot. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. 25 February 2015: 6225–. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger. Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012: 544–. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- ^ Terrence Priestman. Cancer Chemotherapy in Clinical Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. 26 May 2012: 97–. ISBN 978-0-85729-727-3.

- ^ Mohan D, Taylor R, Mackeith JA. Cyproterone acetate and striae. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 1998, 2 (2): 147–148. PMID 24946296. doi:10.3109/13651509809115348.

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Ralph M. Trüeb. Female Alopecia: Guide to Successful Management. Springer Science & Business Media. 26 February 2013: 46– [2016-05-30]. ISBN 978-3-642-35503-5. (原始内容存档于2017-11-05).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Ramsay ID, Rushton DH. Reduced serum vitamin B12 levels during oral cyproterone-acetate and ethinyl-oestradiol therapy in women with diffuse androgen-dependent alopecia. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1990, 15 (4): 277–81. PMID 2145099.

- ^ Benjamin J. Sadock; Virginia A. Sadock. Kaplan and Sadock's Pocket Handbook of Clinical Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010: 582–. ISBN 978-1-60547-264-5.

- ^ Seggane Musisi; Stanley Jacobson. Brain Degeneration and Dementia in Sub-Saharan Africa. Springer. 14 April 2015: 60–. ISBN 978-1-4939-2456-1.

- ^ van der Vange N, Blankenstein MA, Kloosterboer HJ, Haspels AA, Thijssen JH. Effects of seven low-dose combined oral contraceptives on sex hormone binding globulin, corticosteroid binding globulin, total and free testosterone. Contraception. 1990, 41 (4): 345–52. PMID 2139843. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(90)90034-S.

- ^ Stalvey JR. Inhibition of 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-isomerase in mouse adrenal cells: a direct effect of testosterone. Steroids. 2002, 67 (8): 721–31. PMID 12117620. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(02)00023-5.

- ^ Prostate Cancer Research Institute. The Anti-Androgen Withdrawal Response. [2005-08-31]. (原始内容存档于2005-09-11).

- ^ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 William Figg; Cindy H. Chau; Eric J. Small. Drug Management of Prostate Cancer. Springer. 14 September 2010: 71 [2016-06-05]. ISBN 978-1-60327-829-4. (原始内容存档于2020-02-27).

- ^ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Honer C, Nam K, Fink C, Marshall P, Ksander G, Chatelain RE, Cornell W, Steele R, Schweitzer R, Schumacher C. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism by cyproterone acetate and RU486. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63 (5): 1012–20. PMID 12695529. doi:10.1124/mol.63.5.1012.

- ^ Ayub M, Levell MJ. Inhibition of rat testicular 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities by anti-androgens (flutamide, hydroxyflutamide, RU23908, cyproterone acetate) in vitro. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. July 1987, 28 (1): 43–7. PMID 2956461. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90122-1.

- ^ Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J. Clin. Invest. September 1998, 102 (5): 1016–23. PMC 508967 . PMID 9727070. doi:10.1172/JCI3703.

- ^ Christians U, Schmitz V, Haschke M. Functional interactions between P-glycoprotein and CYP3A in drug metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. December 2005, 1 (4): 641–54. PMID 16863430. doi:10.1517/17425255.1.4.641.

- ^ 43.0 43.1 Benno Clemens Runnebaum; Thomas Rabe; Ludwig Kiesel. Female Contraception: Update and Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012: 133–134. ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 A. Hughes; S. H. Hasan; G. W. Oertel; H. E. Voss, F. Bahner, F. Neumann, H. Steinbeck, K.-J. Gräf, J. Brotherton, H. J. Horn, R. K. Wagner. Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Springer Science & Business Media. 27 November 2013: 489, 491. ISBN 978-3-642-80859-3.

- ^ Rabe T, Kowald A, Ortmann J, Rehberger-Schneider S. Inhibition of skin 5 alpha-reductase by oral contraceptive progestins in vitro. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2000, 14 (4): 223–30. PMID 11075290. doi:10.3109/09513590009167685.

- ^ Stárka L, Sulcová J, Broulík P. Effect of cyproterone acetate on the action and metabolism of testosterone in the mouse kidney. Endokrinologie. 1976, 68 (2): 155–63. PMID 1009901.

- ^ Raudrant D, Rabe T. Progestogens with antiandrogenic properties. Drugs. 2003, 63 (5): 463–92. PMID 12600226. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363050-00003.

- ^ Tartagni M, Schonauer LM, De Salvia MA, Cicinelli E, De Pergola G, D'Addario V. Comparison of Diane 35 and Diane 35 plus finasteride in the treatment of hirsutism. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73 (4): 718–23. PMID 10731531. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00633-0.

- ^ Sahin Y, Dilber S, Keleştimur F. Comparison of Diane 35 and Diane 35 plus finasteride in the treatment of hirsutism. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 75 (3): 496–500. PMID 11239530. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01764-7.

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Gutiérrez M, Menéndez L, Ruiz-Gayo M, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A. Cyproterone acetate displaces opiate binding in mouse brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 328 (1): 99–102. PMID 9203575. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)83034-8.

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Luthy IA, Begin DJ, Labrie F. Androgenic activity of synthetic progestins and spironolactone in androgen-sensitive mouse mammary carcinoma (Shionogi) cells in culture. J. Steroid Biochem. 1988, 31 (5): 845–52. PMID 2462135. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90295-6.

- ^ 52.0 52.1 Térouanne B, Tahiri B, Georget V, Belon C, Poujol N, Avances C, Orio F, Balaguer P, Sultan C. A stable prostatic bioluminescent cell line to investigate androgen and antiandrogen effects. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2000, 160 (1-2): 39–49. PMID 10715537. doi:10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00251-8.

- ^ Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 20 December 2010: 80 [27 May 2012]. ISBN 978-0-7817-7968-5. (原始内容存档于2014-07-04).

- ^ Lewis J. Kampel. Dx/Rx: Prostate Cancer: Prostate Cancer. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 20 March 2012: 169 [2016-06-05]. ISBN 978-1-4496-8695-6. (原始内容存档于2014-07-17).

- ^ Neumann F, Kalmus J. Cyproterone acetate in the treatment of sexual disorders: pharmacological base and clinical experience. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. 1991, 98 (2): 71–80. PMID 1838080. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211103.

- ^ Schröder FH. Antiandrogens as monotherapy for prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 1998,. 34 Suppl 3: 12–7. PMID 9854190.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011: 561–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7968-5.

- ^ Pharmacology of the Skin II: Methods, Absorption, Metabolism and Toxicity, Drugs and Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012: 489–. ISBN 978-3-642-74054-1.

- ^ Herbert DC, Schuppler J, Poggel A, Günzel P, El Etreby MF. Effect of cyproterone acetate on prolactin secretion in the female Rhesus monkey. Cell Tissue Res. 1977, 183 (1): 51–60. PMID 411573. doi:10.1007/bf00219991.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Kanhai RC, Hage JJ, van Diest PJ, Bloemena E, Mulder JW. Short-term and long-term histologic effects of castration and estrogen treatment on breast tissue of 14 male-to-female transsexuals in comparison with two chemically castrated men. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000, 24 (1): 74–80 [2016-06-05]. PMID 10632490. doi:10.1097/00000478-200001000-00009. (原始内容存档于2021-05-05).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Lawrence, Anne A. Transgender Health Concerns: 473–505. 2007 [2016-06-05]. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-31334-4_19. (原始内容存档于2020-05-28).

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Paul Peter Rosen. Rosen's Breast Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009: 31–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7137-5.

- ^ Donald RA, Espiner EA, Cowles RJ, Fazackerley JE. The effect of cyproterone acetate on the plasma gonadotrophin response to gonadotrophin releasing hormone. Acta Endocrinologica. April 1976, 81 (4): 680–4. PMID 769466.

- ^ Moltz L, Römmler A, Post K, Schwartz U, Hammerstein J. Medium dose cyproterone acetate (CPA): effects on hormone secretion and on spermatogenesis in men. Contraception. 1980, 21 (4): 393–413. PMID 6771095. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(80)80017-5.

- ^ Rost A, Schmidt-Gollwitzer M, Hantelmann W, Brosig W. Cyproterone acetate, testosterone, LH, FSH, and prolactin levels in plasma after intramuscular application of cyproterone acetate in patients with prostatic cancer. Prostate. 1981, 2 (3): 315–22. PMID 6458025. doi:10.1002/pros.2990020310.

- ^ Jeffcoate WJ, Matthews RW, Edwards CR, Field LH, Besser GM. The effect of cyproterone acetate on serum testosterone, LH, FSH, and prolactin in male sexual offenders. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 1980, 13 (2): 189–95. PMID 6777092. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1980.tb01041.x.

- ^ Grunwald K, Rabe T, Schlereth G, Runnebaum B. [Serum hormones before and during therapy with cyproterone acetate and spironolactone in patients with androgenization]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1994, 54 (11): 634–45. PMID 8719011. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1022355 (德语).

- ^ Salva P, Morer F, Ordoñez J, Rodriguez J. Treatment of idiopathic hirsute women with two combinations of cyproterone acetate. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1983, 3 (2): 129–35. PMID 6237068.

- ^ Schürenkämper P, Lisse K. Effects of cyproterone on the steroid biosynthesis in the human ovary in vitro. Endokrinologie. 1982, 80 (3): 281–6. PMID 7166160.

- ^ Girard J, Baumann JB, Bühler U, Zuppinger K, Haas HG, Staub JJ, Wyss HI. Cyproteroneacetate and ACTH adrenal function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1978, 47 (3): 581–6. PMID 233676. doi:10.1210/jcem-47-3-581.

- ^ 71.0 71.1 Panesar NS, Herries DG, Stitch SR. Effects of cyproterone and cyproterone acetate on the adrenal gland in the rat: studies in vivo and in vitro. J. Endocrinol. 1979, 80 (2): 229–38. PMID 438696. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0800229.

- ^ El Etreby MF. Effect of cyproterone acetate, levonorgestrel and progesterone on adrenal glands and reproductive organs in the beagle bitch. Cell Tissue Res. 1979, 200 (2): 229–43. PMID 487397. doi:10.1007/bf00236416.

- ^ Savage DC, Swift PG. Effect of cyproterone acetate on adrenocortical function in children with precocious puberty. Arch. Dis. Child. 1981, 56 (3): 218–22. PMC 1627152 . PMID 6260040. doi:10.1136/adc.56.3.218.

- ^ Stivel MS, Kauli R, Kaufman H, Laron Z. Adrenocortical function in children with precocious sexual development during treatment with cyproterone acetate. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 1982, 16 (2): 163–9. PMID 6279337. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1982.tb03160.x.

- ^ Hague WM, Munro DS, Sawers RS, Duncan SL, Honour JW. Long-term effects of cyproterone acetate on the pituitary adrenal axis in adult women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982, 89 (12): 981–4. PMID 6216913. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb04650.x.

- ^ Mercier L, Miller PA, Simons SS. Antiglucocorticoid steroids have increased agonist activity in those hepatoma cell lines that are more sensitive to glucocorticoids. J. Steroid Biochem. 1986, 25 (1): 11–20. PMID 2875214. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(86)90275-x.

- ^ Poulin R, Baker D, Poirier D, Labrie F. Multiple actions of synthetic 'progestins' on the growth of ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells: an in vitro model for the simultaneous assay of androgen, progestin, estrogen, and glucocorticoid agonistic and antagonistic activities of steroids. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1991, 17 (3): 197–210. PMID 1645605. doi:10.1007/BF01806369.

- ^ Pham-Huu-Trung MT, de Smitter N, Bogyo A, Girard F. Effects of cyproterone acetate on adrenal steroidogenesis in vitro. Horm. Res. 1984, 20 (2): 108–15. PMID 6237971. doi:10.1159/000179982.

- ^ Lambert A, Mitchell RM, Robertson WR. On the site of action of the anti-adrenal steroidogenic effect of cyproterone acetate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985, 34 (12): 2091–5. PMID 2988566. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(85)90400-9.

- ^ Heinze F, Teller WM, Fehm HL, Joos A. The effect of cyproterone acetate on adrenal cortical function in children with precocious puberty. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1978, 128 (2): 81–8. PMID 208851. doi:10.1007/bf00496993.

- ^ 81.0 81.1 Frith RG, Phillipou G. 15-Hydroxycyproterone acetate and cyproterone acetate levels in plasma and urine. J. Chromatogr. 1985, 338 (1): 179–86. PMID 3160716. doi:10.1016/0378-4347(85)80082-7.

- ^ Bhargava AS, Seeger A, Günzel P. Isolation and identification of 15-beta-hydroxy cyproterone acetate as a new metabolite of cyproterone acetate in dog, monkey and man. Steroids. 1977, 30 (3): 407–18. PMID 413211. doi:10.1016/0039-128x(77)90031-9.

- ^ 83.0 83.1 Bhargava AS, Kapp JF, Poggel HA, Heinick J, Nieuweboer B, Günzel P. Effect of cyproterone acetate and its metabolites on the adrenal function in man, rhesus monkey and rat. Arzneimittelforschung. 1981, 31 (6): 1005–9. PMID 6266428.

- ^ Broulik PD, Starka L. Corticosteroid-like effect of cyproterone and cyproterone acetate in mice. Experientia. 1975, 31 (11): 1364–5. PMID 1204803. doi:10.1007/bf01945829.

- ^ van Wayjen RG, van den Ende A. Effect of cyproterone acetate on pituitary-adrenocortical function in man. Acta Endocrinol. 1981, 96 (1): 112–22. PMID 6257015. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0960112.

- ^ Schürmeyer T, Graff J, Senge T, Nieschlag E. Effect of oestrogen or cyproterone acetate treatment on adrenocortical function in prostate carcinoma patients. Acta Endocrinol. 1986, 111 (3): 360–7. PMID 2421511. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1110360.

- ^ van Wayjen RG, van den Ende A. Experience in the long-term treatment of patients with hirsutism and/or acne with cyproterone acetate-containing preparations: efficacy, metabolic and endocrine effects. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 1995, 103 (4): 241–51. PMID 7584530. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211357.

- ^ Holdaway IM, Croxson MS, Evans MC, France J, Sheehan A, Wilson T, Ibbertson HK. Effect of cyproterone acetate on glucocorticoid secretion in patients treated for hirsutism. Acta Endocrinol. 1983, 104 (2): 222–6. PMID 6227191. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1040222.

- ^ John A. Thomas. Endocrine Toxicology, Second Edition. CRC Press. 12 March 1997: 152– [2016-06-05]. ISBN 978-1-4398-1048-4. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ Nick Panay. Managing the Menopause. Cambridge University Press. 31 August 2015: 126–. ISBN 978-1-107-45182-7.

- ^ Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority. Cyproterone Acetate (PDF). 2006-04-11 [2016-06-05]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2007-09-28).

- ^ Giorgi EP, Shirley IM, Grant JK, Stewart JC. Androgen dynamics in vitro in the human prostate gland. Effect of cyproterone and cyproterone acetate. Biochem J. 1 March 1973, 132 (3): 465–74. PMC 1177610 . PMID 4125095.

- ^ Fischl FH. Pharmacology of Estrogens and Gestagens. (PDF). Krause & Pachemegg (编). Menopause andropause. (PDF). Gablitz: Krause und Pachernegg. 2001: 33–50 [2016-06-05]. ISBN 3-901299-34-3. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2021-02-13).

- ^ New Zealand Medicines; Medical Devices Safety Authority. Data Sheet: Diane 35 ED. 2005-12-09. (原始内容存档于2007-01-08).

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

pmid16112947的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Anderson J. The role of antiandrogen monotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2003, 91 (5): 455–61. PMID 12603397. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04026.x.

- ^ Neumann F, Elger W. Permanent changes in gonadal function and sexual behaviour as a result of early feminization of male rats by treatment with an antiandrogenic steroid. Endokrinologie. 1966, 50: 209–225.

- ^ Forsberg JG, Jacobsohn D, Norgren A. Modifications of reproductive organs in male rats influenced prenatally or pre- and postnatally by an "antiandrogenic" steroid (Cyproterone). Zeitschrift Für Anatomie Und Entwicklungsgeschichte (Springer). 1968, 127 (2): 175–86 [2016-10-02]. PMID 5692718. doi:10.1007/bf00521983. (原始内容存档于2017-05-23).

- ^ Tamm J, Voigt KD, Schönrock M, Ludwig E. The effect of orally administered cyproterone on the serum production in human subjects. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). Jan 1970, 63 (1): 50–8. PMID 5467021.

- ^ Von Schumann HJ. Resocialization of sexually abnormal patients by a combination of anti-androgen administration and psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom. 1972, 20 (6): 321–32.