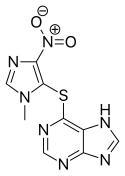

硫唑嘌呤

硫唑嘌呤(INN:azathioprine),在台湾的商品中,以安思平或移护宁两个商品名较为人熟知,是一种免疫抑制剂。[4]用于治疗类风湿性关节炎、肉芽肿并多发性血管炎、克隆氏症、溃疡性结肠炎、全身性红斑狼疮,以及主要在肾脏移植后防止移植排斥反应。此药物被国际癌症研究机构列为一类人类致癌物。[4][5][6][7]给药方式为口服给药或是静脉注射。[4]

| |

| |

| 临床资料 | |

|---|---|

| 读音 | /ˌæzəˈθaɪəˌpriːn/[1] |

| 商品名 | Azasan、Imuran、Jayempi及其他 |

| 其他名称 | AZA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682167 |

| 核准状况 | |

| 怀孕分级 |

|

| 给药途径 | 口服给药, 静脉注射 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | 60±31% |

| 血浆蛋白结合率 | 20–30% |

| 药物代谢 | 不经由酵素作用而活化,主要受到黄嘌呤氧化酶的抑制而失去活性。 |

| 生物半衰期 | 26–80分钟(硫唑嘌呤本身) 3–5 hours (药物及其代谢物) |

| 排泄途径 | 肾脏, 98%为代谢物 |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 446-86-6( 55774-33-9 (sodium salt)) |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.525 |

| 化学信息 | |

| 化学式 | C9H7N7O2S |

| 摩尔质量 | 277.26 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| 熔点 | 238至245 °C(460至473 °F) |

| |

| |

使用此药物常见的副作用有骨髓抑制和呕吐。[4]在有硫嘌呤甲基转移酶遗传缺陷的族群中尤其容易发生骨髓抑制现象。其他会导致严重的危险因子有罹患某些癌症的风险会因而增加。[4]个体于怀孕期间使用可能会对胎儿造成伤害。硫唑嘌呤属于抗代谢物家族中的嘌呤类似物亚类。[4][8]它透过硫鸟嘌呤来干扰细胞制造RNA和DNA的过程而发挥作用。[4][8]

硫唑嘌呤是由两位美国科学家 - 乔治·H·希钦斯和格特鲁德·B·埃利恩于1957年成功合成。[8]它已列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中。[9]此药物在美国2018年最常使用处方药中排名第358,开立的处方笺数量超过80万张。[10]

医疗用途

编辑单独使用硫唑嘌呤或与其他免疫抑制剂合并使用,以预防器官移植后发生的排斥反应,并治疗一系列自体免疫疾病,包括类风湿性关节炎、天疱疮、全身性红斑狼疮、贝赛特氏症和其他形式的血管炎、自体免疫性肝炎、异位性皮肤炎、重症肌无力、视神经脊髓炎谱系疾病(又称德维克病(Devic's disease))、限制性肺病等。[11]它也是治疗发炎性肠道疾病(如克隆氏症和溃疡性结肠炎)和多发性硬化症的重要药物,这种药物能有效减少患者对类固醇的依赖。[12]

此药物被美国食品药物管理局(FDA)批准用于抑制人体对移植而来肾脏产生排斥的问题和治疗类风湿性关节炎。[13]

器官移植

编辑硫唑嘌呤用于预防受者肾脏或肝脏同种异体移植器官的排斥反应,通常会与其他药物结合使用,包括皮质类固醇、其他免疫抑制剂和局部放射治疗。[14][15]给药方案在移植当时或随后两天内开始。[13]

类风湿性关节炎

编辑硫唑嘌呤具有类风湿关节炎缓解药(DMARD)的作用,而被用于治疗成人类风湿性关节炎的征兆和症状。[16]非类固醇抗发炎药和类固醇可与硫唑嘌呤合用或继续使用(如果已使用),但不建议与其他类风湿关节炎缓解药合用。[13]

发炎性肠道疾病

编辑硫唑嘌呤常用于治疗中重度克隆氏症,[17]以维持疾病缓解,特别是对于依赖类固醇的患者。[18]并有助于治疗瘘管型克隆氏症患者。[19]但其作用缓慢,可能需要几个才能达到临床反应。[20]

使用硫唑嘌呤治疗与罹患淋巴瘤风险增加有关,但尚不清楚这是由于此药物,还是与克隆氏症相关的易感性所致。[21]较低剂量的硫唑嘌呤可用于治疗难治性或类固醇依赖性克隆氏症的儿童,且副作用较少。[22]它也可以用于预防溃疡性结肠炎复发。[23]

其他

编辑不良反应

编辑恶心和呕吐是常见的不良反应,尤其是在治疗开始时。这种情况可透过饭后服用硫唑嘌呤或静脉推注来解决。

可能与过敏反应有关的副作用包括头晕、腹泻、疲劳和皮疹。头发掉落常见于器官移植患者。由于硫唑嘌呤会抑制骨髓,患者可能会出现贫血,而更容易感染。建议个体在治疗期间定期监测其血球计数。[13][25]急性胰腺炎也可能发生,特别是在克隆氏症患者。[26]

此药物被国际癌症研究机构列为一类人类致癌物。[27]

癌症

编辑美国卫生及公共服务部国家毒物计划在发布的第12次致癌物报告中将硫唑嘌呤列为人类致癌物,声称"基于充分对人类的研究证据,该物质被认定为人类致癌物。" [28]FDA要求从2009年8月开始在药物包装上添加有关某些癌症风险增加的警告。[29]

皮肤癌

编辑在器官移植患者中,皮肤癌的发生率是一般人群的50至250倍。高达60%至90%的患者于移植手术后20年会出现皮肤癌问题。在器官移植手术中使用免疫抑制剂(包括硫唑嘌呤),已被发现与皮肤癌发生率增加有关联。[30]

过量

编辑人体对于使用大单剂量通常耐受性良好。有一名患者一次服用7.5克硫唑嘌呤(150片),除呕吐、白血球数略有下降、肝功能指数略有变化外,没出现任何相关症状。长期过量服用的主要症状是不明原因的感染、口疮和自发性出血,这些都是骨髓受到抑制的后果。[25]

药物交互作用

编辑其他嘌呤类似物,如别嘌醇,会抑制黄嘌呤氧化酶(分解硫唑嘌呤的酵素),而增加硫唑嘌呤的毒性。[31]然而,低剂量的别嘌呤醇已被证明可安全增强硫唑嘌呤的疗效,特别是在对炎症性肠病治疗无反应的患者。[32][33][34]但仍然会导致淋巴球计数降低和感染率升高,因此个体于使用这种组合时需仔细监测。[35][36]

硫唑嘌呤会降低抗凝血剂华法林和非去极化肌肉松弛剂的作用,但会增加去极化肌肉松弛剂的作用。它还会干扰[[维生素B3]],导致至少有一例糙皮病和致命骨髓衰竭的报导。[37]

怀孕与哺乳

编辑硫唑嘌呤为具细胞毒性的药物,传统上被列为哺乳期用药禁忌。然而,根据美国临床药理学家Thomas Hale在其名为"Medications and Mothers' Milk"的著作中,将硫唑嘌呤的哺乳风险评估为"L3",即中等安全等级。[41]

药理学

编辑药物动力学

编辑硫唑嘌呤经由个体的肠道吸收达到约88%。由于药物在肝脏中部分失活,个别患者的生物利用度差异很大(介于30%至90%之间)。药物本身及其代谢物在摄入1-2小时后达到最高血浆浓度,硫唑嘌呤的平均血浆生物半衰期为26至80分钟,药物加代谢物的平均血浆生物半衰期为3-5小时。 有20%至30%在血液循环时与血浆蛋白结合。[11][25][42][43]

作用机转

编辑硫唑嘌呤会抑制嘌呤合成,而嘌呤为生产DNA和RNA时所需。嘌呤合成受到抑制,表示用于合成白血球的DNA和RNA会减少,进而发生免疫抑制。

硫唑嘌呤最初由两位美国科学家 - 乔治·H·希钦斯和格特鲁德·B·埃利恩于1957年合成,一开始作为化学治疗药物之用。[45][46][47]美国医师Robert Schwartz于1958年研究硫鸟嘌呤(6-Mercaptopurine)对免疫反应的影响,发现它可显著抑制抗体形成。

英国器官移植先驱罗伊·侃基于英国生物学家彼得·梅达沃和格特鲁德·B·埃利恩对移植组织和器官排斥的免疫学基础的研究,以及Robert Schwartz对硫鸟嘌呤的研究,而引入硫鸟嘌呤作为肾脏和心脏移植的实验性免疫抑制剂。[48]当罗伊·侃向格特鲁德·B·埃利恩询问相关化合物的问题时,后者建议使用硫唑嘌呤,罗伊·侃发现硫唑嘌呤作用优于硫鸟嘌呤的(同样有效,但对骨髓毒性较低)。[45][11]

于1962年4月进行的世界首次肾脏移植给无血缘关系的受体(同种异体移植)的成功案例,使用的药物有硫唑嘌呤和泼尼松(一种糖皮质素)。.[11][49]这种以硫唑嘌呤和糖皮质素为基础的双重药物疗法在往后许多年一直是标准的抗排斥做法,直到环孢素于1978年被引入临床使用(同样经由罗伊·侃引入)才发生改变。

由于环孢素能显著延长移植患者的存活期,特别是在心脏移植方面,因此已逐渐取代硫唑嘌呤成为免疫抑制的首选药物之一。[50][51][52]另由一种抗排斥药物霉酚酸,其价格较高,但因副作用如骨髓抑制、感染风险以及急性排斥反应发生率均较低,而成为另一种备受青睐的替代选择,也在器官移植领域中取代部分硫唑嘌呤的应用。[15][53]

参考文献

编辑- ^ Azathioprine. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ Jayempi EPAR. European Medicines Agency. 2021-04-20 [2023-03-04].

- ^ Jayempi Product information. Union Register of medicinal products. [2023-03-03].

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Azathioprine. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [2016-12-08]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-20).

- ^ Axelrad JE, Lichtiger S, Yajnik V. Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: The role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology (Review). May 2016, 22 (20): 4794–4801. PMC 4873872 . PMID 27239106. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i20.4794 .

- ^ Singer O, McCune WJ. Update on maintenance therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. May 2017, 29 (3): 248–253. PMID 28306595. S2CID 35805200. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000382.

- ^ Jordan N, D'Cruz D. Current and emerging treatment options in the management of lupus. ImmunoTargets and Therapy. 2016, 5: 9–20. PMC 4970629 . PMID 27529058. doi:10.2147/ITT.S40675 .

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Sami N. Autoimmune Bullous Diseases: Approach and Management. Springer. 2016: 83. ISBN 9783319267289. (原始内容存档于2016-12-21).

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771 . WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Azathioprine - Drug Usage Statistics. ClinCalc. [2022-10-07].

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Patel AA, Swerlick RA, McCall CO. Azathioprine in dermatology: the past, the present, and the future. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. September 2006, 55 (3): 369–389. PMID 16908341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.059.

- ^ Evans WE. Pharmacogenetics of thiopurine S-methyltransferase and thiopurine therapy. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. April 2004, 26 (2): 186–191. PMID 15228163. S2CID 34015182. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00018.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Azathioprine, Azathioprine Sodium. AHFS Drug Information 2012. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. January 2012. ISBN 978-1-58528-267-8.

- ^ Nuyttens JJ, Harper J, Jenrette JM, Turrisi AT. Outcome of radiation therapy for renal transplant rejection refractory to chemical immunosuppression. Radiotherapy and Oncology. January 2005, 74 (1): 17–19. PMID 15683663. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2004.08.011.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Remuzzi G, Lesti M, Gotti E, Ganeva M, Dimitrov BD, Ene-Iordache B, Gherardi G, Donati D, Salvadori M, Sandrini S, Valente U, Segoloni G, Mourad G, Federico S, Rigotti P, Sparacino V, Bosmans JL, Perico N, Ruggenenti P. Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine for prevention of acute rejection in renal transplantation (MYSS): a randomised trial. Lancet. August 2004, 364 (9433): 503–512. PMID 15302193. S2CID 22033113. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16808-6.

- ^ Suarez-Almazor ME, Spooner C, Belseck E. Suarez-Almazor ME , 编. Azathioprine for treating rheumatoid arthritis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000, 2010 (4): CD001461. PMC 8406472 . PMID 11034720. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001461.

- ^ Sandborn WJ. Azathioprine: state of the art in inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. Supplement. 1998, 225 (234): 92–99. PMID 9515759. doi:10.1080/003655298750027290.

- ^ Biancone L, Tosti C, Fina D, Fantini M, De Nigris F, Geremia A, Pallone F. Review article: maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. June 2003, 17 (Suppl 2): 31–37. PMID 12786610. S2CID 23554085. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.17.s2.20.x.

- ^ Rutgeerts P. Review article: treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. October 2004, 20 (Suppl 4): 106–110. PMID 15352905. S2CID 71968695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02060.x .

- ^ Rutgeerts P. Review article: treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. October 2004, 20 (Suppl 4): 106–110. PMID 15352905. S2CID 71968695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02060.x .

- ^ Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. August 2005, 54 (8): 1121–1125. PMC 1774897 . PMID 16009685. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.049460.

- ^ Kirschner BS. Safety of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. October 1998, 115 (4): 813–821. PMID 9753482. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70251-3 .

- ^ Timmer A, Patton PH, Chande N, McDonald JW, MacDonald JK. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. May 2016, 2016 (5): CD000478. PMC 7034525 . PMID 27192092. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000478.pub4.

- ^ Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Azathioprine therapy for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2001, 10 (3): 152–153. PMID 11315344. S2CID 71558242. doi:10.1191/096120301676669495.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Jasek, W (编). Austria-Codex 62nd. Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. 2007: 4103–9. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4 (德语).

- ^ Weersma RK, Peters FT, Oostenbrug LE, van den Berg AP, van Haastert M, Ploeg RJ, Posthumus MD, Homan van der Heide JJ, Jansen PL, van Dullemen HM. Increased incidence of azathioprine-induced pancreatitis in Crohn's disease compared with other diseases. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. October 2004, 20 (8): 843–850. PMID 15479355. S2CID 21873238. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02197.x.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Azathioprine. Summaries & Evaluations. 1987, (suppl. 7): 119. (原始内容存档于2006-06-04).

- ^ National Toxicology Program. Report On Carcinogens – Twelfth Edition – 2011. National Toxicology Program. 10 June 2011 [2012-06-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-07-16).

- ^ FDA: Cancer Warnings Required for TNF Blockers. FDA. 2009-08-04 [2012-06-20]. (原始内容存档于2012-07-03).

- ^ Skin cancer alert for organ drug. BBC Online. BBC News. 2005-09-15 [2012-06-10]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-14).

- ^ Sahasranaman S, Howard D, Roy S. Clinical pharmacology and pharmacogenetics of thiopurines. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. August 2008, 64 (8): 753–767. PMID 18506437. S2CID 27475772. doi:10.1007/s00228-008-0478-6.

- ^ Chocair P, Duley J, Simmonds HA, Cameron JS, Ianhez L, Arap S, Sabbaga E. Low-dose allopurinol plus azathioprine/cyclosporin/prednisolone, a novel immunosuppressive regimen. Lancet. July 1993, 342 (8863): 83–84. PMID 8100914. S2CID 13419507. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)91287-V.

- ^ Sparrow MP, Hande SA, Friedman S, Lim WC, Reddy SI, Cao D, Hanauer SB. Allopurinol safely and effectively optimizes tioguanine metabolites in inflammatory bowel disease patients not responding to azathioprine and mercaptopurine. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. September 2005, 22 (5): 441–446. PMID 16128682. S2CID 9356163. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02583.x .

- ^ Sparrow MP, Hande SA, Friedman S, Cao D, Hanauer SB. Effect of allopurinol on clinical outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease nonresponders to azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. February 2007, 5 (2): 209–214. PMID 17296529. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2006.11.020 .

- ^ Govani SM, Higgins PD. Combination of thiopurines and allopurinol: adverse events and clinical benefit in IBD. Journal of Crohn's & Colitis. October 2010, 4 (4): 444–449. PMC 3157326 . PMID 21122542. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2010.02.009.

- ^ Ansari A, Patel N, Sanderson J, O'Donohue J, Duley JA, Florin TH. Low-dose azathioprine or mercaptopurine in combination with allopurinol can bypass many adverse drug reactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. March 2010, 31 (6): 640–647. PMID 20015102. S2CID 6000856. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04221.x .

- ^ Oliveira A, Sanches M, Selores M. Azathioprine-induced pellagra. The Journal of Dermatology. October 2011, 38 (10): 1035–1037. PMID 21658113. S2CID 3396280. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01189.x.

- ^ Mehta DK. British National Formulary, Issue 45. London: British Medical Association. March 2003. ISBN 978-0-85369-555-4. 已忽略未知参数

|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ Cleary BJ, Källén B. Early pregnancy azathioprine use and pregnancy outcomes. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology. July 2009, 85 (7): 647–654. PMID 19343728. doi:10.1002/bdra.20583.

- ^ Tagatz GE, Simmons RL. Pregnancy after renal transplantation. Annals of Internal Medicine. January 1975, 82 (1): 113–114. PMID 799904. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-82-1-113.

- ^ Hale TW. Medications and Mothers' Milk: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. Hale Pub. April 2010. ISBN 978-0-9823379-9-8.

- ^ Dinnendahl, V; Fricke, U (编). Arzneistoff-Profile 2 25th. Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. 2011. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3 (德语).

- ^ Steinhilber D, Schubert-Zsilavecz M, Roth HJ. Medizinische Chemie. Stuttgart: Deutscher Apotheker Verlag. 2005: 340. ISBN 978-3-7692-3483-1 (德语).

- ^ Hempel, Georg. Handbook of Analytical Separations, 2020. Elsevier B.V. [2024-11-28]. ISSN 1567-7192.

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Science. April 1989, 244 (4900): 41–47. Bibcode:1989Sci...244...41E. PMID 2649979. doi:10.1126/science.2649979.

- ^ Elion GB, Callahan SW, Hitchings GH, Rundles RW. The metabolism of 2-amino-6-[(1-methyl-4-nitro-5-imidazolyl)thio]purine (B.W. 57-323) in man. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports. July 1960, 8: 47–52. PMID 13849699.

- ^ Thiersch JB. Effect of 6-(1'-methyl-4'-nitro-5'-imidazolyl)-mercaptopurine and 2-amino-6-(1'-methyl-4'-nitro-5'-imidazolyl)-mercaptopurine on the rat litter in utero. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. December 1962, 4 (3): 297–302. PMID 13980986. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0040297.

- ^ Calne RY. The rejection of renal homografts. Inhibition in dogs by 6-mercaptopurine. Lancet. February 1960, 1 (7121): 417–418. PMID 13807024. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(60)90343-3.

- ^ Murray JE, Merrill JP, Harrison JH, Wilson RE, Dammin GJ. Prolonged survival of human-kidney homografts by immunosuppressive drug therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. June 1963, 268 (24): 1315–1323. PMID 13936775. doi:10.1056/NEJM196306132682401.

- ^ Bakker RC, Hollander AA, Mallat MJ, Bruijn JA, Paul LC, de Fijter JW. Conversion from cyclosporine to azathioprine at three months reduces the incidence of chronic allograft nephropathy. Kidney International. September 2003, 64 (3): 1027–1034. PMID 12911553. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00175.x .

- ^ Henry ML, Sommer BG, Ferguson RM. Beneficial effects of cyclosporine compared with azathioprine in cadaveric renal transplantation. American Journal of Surgery. November 1985, 150 (5): 533–536. PMID 2998215. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(85)90431-3.

- ^ Modry DL, Oyer PE, Jamieson SW, Stinson EB, Baldwin JC, Reitz BA, Dawkins KD, McGregor CG, Hunt SA, Moran M. Cyclosporine in heart and heart-lung transplantation. Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien de Chirurgie. May 1985, 28 (3): 274–80, 282. PMID 3922606.

- ^ Woodroffe R, Yao GL, Meads C, Bayliss S, Ready A, Raftery J, Taylor RS. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of newer immunosuppressive regimens in renal transplantation: a systematic review and modelling study. Health Technology Assessment. May 2005, 9 (21): 1–194. PMID 15899149. doi:10.3310/hta9210 .

延伸阅读

编辑- Dean L. Azathioprine Therapy and TPMT Genotype. Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al (编). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 2012. PMID 28520349. Bookshelf ID: NBK100661.