抗氧化剂

抗氧化剂是指能减缓或防止氧化作用的分子(常专指生物体中)。氧化是一种使电子自物质转移至氧化剂的化学反应,过程中可生成自由基,进而启动链反应。当链反应发生在细胞中,细胞便會受到破坏或凋亡。抗氧化剂则能去除自由基,终止连锁反应并且抑制其他氧化反应,同时其本身被氧化。抗氧化剂通常是还原剂,例如硫醇、抗坏血酸、多酚类。[1]

抗氧化剂也是一种汽油中重要的添加剂。它可以防止油料在储存过程中氧化变质形成胶质沉淀从而妨碍内燃机的正常运转。[2]

虽然氧化反应十分重要,但它也能对生命体造成伤害;因此,动植物演化出多种抗氧化剂,如常见的谷胱甘肽、维生素C与维生素E,过氧化氢酶、超氧化物歧化酶等酶,以及各种过氧化酶。低阶的抗氧化剂或抗氧化酶的抑制剂,则会引发氧化应激,导致细胞的损伤和死亡。

由于氧化应激是一些许多疾病的重要组成部分,所以药理学对抗氧化剂的使用,特别是在对中风和神經退化性疾病的治疗中有深入研究。此外氧化应激也是一些疾病的诱因和结果。

抗氧化剂被广泛应用在营养补充剂中。对于一些疾病比如癌症、冠心病甚至高原反应的预防作用已经得到研究。尽管先前的初步研究表明补充抗氧化剂可能促进健康,但后来对一部分抗氧化剂进行大量临床试验得到的结果并没有显示出补充抗氧化剂(维生素C)的好处,甚至发现大剂量补充某些公认的抗氧化剂(硒、维生素E)会使罹患某些疾病的相对风险上升一到五个百分点[3][4]。瑞典哥德堡大學薩爾葛蘭斯卡研究院(Sahlgrenska Academy)研究指出,抗氧化劑會加速肺癌及其他癌細胞的進展惡化[5]。 另外也有一个持续数年的跟踪研究证实大剂量的抗氧化剂可以使罹患心血管疾病的风险降低65%,但具体机理不明[6]。抗氧化剂在其他诸多领域也有用途,比如食品和化妆品防腐剂以及延缓橡胶的老化降解。

抗氧化剂的历史

编辑为了适应从海洋生物演变为陆地生物,陆生植物开始产生海洋生物所不具有的抗氧化剂,比如维生素C、多酚和生育酚。五千万年到两亿万年前,特别是在侏罗纪时代,被子植物植物在进化的过程中发展出了许多抗氧化的天然色素,来作为一种抵御光合作用副产物活性氧类物质的化学手段[7]。本来抗氧化剂一词特指那类可以防止氧气消耗的化学物质。在19世纪末至20世纪初,广泛研究集中在重要的工业生产过程对抗氧化剂的使用上,比如防止金属腐蚀、橡胶的硫化、由燃料聚合导致的内燃机积垢等[8]。

生物学对抗氧剂的研究早期集中在如何使用抗氧化剂来避免不饱和脂肪酸氧化引起的酸败[9]。可以通过将一块脂肪置于一个充氧的密封容器后,对其氧化速率进行测定以度量抗氧化活性。然而随着具有抗氧化作用的维生素A、C、E的发现和确认,人们意识到抗氧化剂在生物体内起到生化作用的重要性[10][11]。当认识到具有抗氧化活性的物质可能本身就容易被氧化的事实后,对抗氧化剂可能作用机理的探索首先开始。通过研究維生素E如何防止脂质过氧化,明确了抗氧化剂作为还原剂通过与活性氧物质反应来避免活性氧物质对细胞的破坏,达到抗氧化的效果。[12]

生物體應對氧化的方法

编辑对于生物体的代谢有一种自相矛盾的情况,虽然大部分地球上的生物需要氧气来维持生存,但同时氧气又是一种高反应活性的分子,可以通过产生活性氧物质破坏生物体[13]。所以生物体中建立了一套由抗氧化的代谢产物和酶构成的复杂网络系统,通过有抗氧化作用的代谢中间体和产物与酶之间的协同配合使得重要的细胞成分比如DNA、蛋白质和脂类免受氧化损伤[1][14]。抗氧化系统大体上通过两种方式实现抗氧化作用,一种是通过阻止活性氧物质的产生来实现,另一种是在这些活性物质对细胞的重要成分造成损伤之前將其清除以达到抗氧化作用的[1][13]。然而这些活性氧物质也有重要的细胞功能,比如在生化反应中充当氧化还原信号分子。因此生物体中抗氧化系统的作用不是氧化性物质彻底地全部清除,而是将这些物质保持在适当的水平[15]。

在细胞内产生的活性氧物种包括过氧化氢(H2O2)、次氯酸(HClO)、自由基例如羟基自由基(·OH)和超氧根(O2−)[16]。羟基自由基特别不稳定,能无特异性地迅速与大多数生物分子反应。这类物种主要是由金属催化过氧化氢还原(比如芬顿反应)产生的[17]。这些氧化剂通过引发链反应比如脂质的过氧化反应、或氧化DNA和蛋白质破坏细胞[1]。受到损害的DNA如果没有得到修复会引起突变、诱发癌症[18][19]。对蛋白质造成的损伤会使酶的活性受到抑制,蛋白质发生变性或降解[20]。

人体新陈代谢产生能量的过程中需要消耗氧气生成活性氧物种[21]。这个过程中,电子传递链的几个步骤能产生副产物超氧化物阴离子[22]。特别重要的是复合物III中的辅酶Q在被还原的过程中会变成高活性的自由基中间体(Q·−)。这种不稳定的中间体会发生电子“泄漏”(丢失电子),“泄漏”的电子跳出正常的电子传递链,直接将氧分子还原生成超氧负离子[23]。过氧化物也可以由还原态的黄素蛋白比如复合体Ⅰ的氧化产生[24]。然而,尽管这些酶会生成氧化剂,但是目前尚不清楚电子传递链相比其他同样可以产生过氧化物的生化过程是否更为重要[25][26]。在植物、藻类和蓝菌进行光合作用的过程中尤其是在高辐照强度下,同样会产生活性氧物种,但是类胡萝卜素作为光保护剂吸收过度强光保护细胞[27],藻类、蓝菌中所含的大量碘和硒也能抵消高辐照强度对细胞造成的氧化损伤[28],类胡萝卜素、碘和硒作为抗氧化剂通过与被过度还原的光合反应中心反应避免活性氧物种的产生[29][30]。

抗氧化代谢物

编辑抗氧化剂可根据溶解性分为两大类:水溶性抗氧化剂和脂溶性抗氧化剂。水溶性抗氧化剂通常存在于细胞质基质和血浆中,脂溶性抗氧化剂则保护细胞膜的脂质免受过氧化[1]。这些化合物或在人体内生物合成或通过膳食摄取[14]。不同抗氧化剂以一定范围的浓度分布于体液和组织中。谷胱甘肽和辅酶Q10主要存在于细胞中,而其他抗氧化剂比如尿酸它们的分布更为广泛(详见下表)。一些抗氧化剂由于既有抗氧化作用也是重要的病原体和致病因子,所以只存在于某些特定机体组织中[31]。

一些化合物通过与过渡金属配位螯合来阻止金属在细胞中催化自由基的产生,从而起到抗氧化防御的作用。这种抗氧化防御手段中特别重要的一点是要将铁离子通过配位螯合隔离起来,因为铁离子是一些铁结合蛋白(iron-binding proteins)比如運鐵蛋白和鐵蛋白能发挥作用的关键[26]。硒和锌通常被认为是抗氧化营养素(antioxidant nutrients),这两种元素本身没有抗氧化作用但会对一些抗氧化酶的活性起到作用。

| 抗氧化代谢产物 | 溶解性 | 人血清中的浓度(μM)[32] | 肝组织中的浓度(μmol/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 抗坏血酸(维生素C) | 水溶性 | 50 – 60[33] | 260(人体)[34] |

| 谷胱甘肽 | 水溶性 | 4[35] | 6,400(人体)[34] |

| 硫辛酸 | 水溶性 | 0.1 – 0.7[36] | 4 – 5(白鼠)[37] |

| 尿酸 | 水溶性 | 200 – 400[38] | 1,600 (人体)[34] |

| 胡萝卜素 | 脂溶性 | β-胡萝卜素: 0.5 – 1[39] | 5(人体,全部胡萝卜素)[41] |

| α-生育酚(维生素E) | 脂溶性 | 10 – 40[40] | 50(人体)[34] |

| 泛醌(辅酶Q) | 脂溶性 | 5[42] | 200(人体)[43] |

尿酸

编辑尿酸是血液中浓度最高的抗氧剂。尿酸是嘌呤代谢的中间产物[44],由黄嘌呤通过黄嘌呤氧化酶氧化产生,是一种有抗氧化性的氧嘌呤(oxypurine)。在大部分陆地动物体内,尿酸氧化酶可催化尿酸进一步氧化成尿囊素[45],但人和一些高级灵长类动物的尿酸氧化酶基因不发挥作用,所以尿酸在体内不会进一步分解[45][46]。尿酸氧化酶功能在人类进化过程中丢失的原因仍是一个有待探讨的问题[47][48]。尿酸的抗氧化性使研究者推测这种突变有利于早期的灵长类动物和人类[48][49][50]。对生物高海拔环境适应性的研究结果支持这样一种假设:尿酸作为抗氧化剂可以缓解由高原低氧引发的氧化应激[51]。在氧化应激所促发疾病的动物实验中发现尿酸可以预防或缓解疾病,研究者将其归因于尿酸的抗氧化特性[52]。关于尿酸抗氧化机理的研究结果也支持这一提议[53]。

对于多发性硬化症,Gwen Scott解释了尿酸作为抗氧化剂对于多发性硬化症的重要意义,血清中的尿酸水平与多发性硬化症的发生率呈相反关系,因为多发性硬化症的病人血清中的尿酸水平低,而患有痛风的病人很少患有这种疾病。更重要的是尿酸可用于治疗实验性质的一种多发性硬化症的动物模型:变态反应性脑脊髓症[52][54][55]。总之,虽然尿酸作为抗氧化剂的机理得到广泛的支持,但声称体内尿酸水平影响患多发性硬化症风险的说法仍存争议[56][57],且需要更多的研究。

尿酸是所有血液抗氧化剂中浓度最高的,它的贡献佔人類血清中总抗氧化能力的一半[58]。尿酸的抗氧化活性很复杂,它不能与一些氧化剂比如超氧化物反应,但能对过氧亚硝基阴离子(peroxynitrite)[59]、过氧化物和次氯酸起到抗氧化作用[44]。

抗坏血酸

编辑抗坏血酸(或称维生素C)是植物和动物体内的单糖氧化-还原催化剂。在灵长类动物的进化过程中,因为发生了突变,导致机体中一种用于合成维生素C所必需的酶丢失,所以人类必须从饮食中摄取维生素C[60]。其他大部分动物都具备在体内合成维生素C的功能因而无需通过食物补充[61]。通过氧化L-脯氨酸残基得到4-羟基-L-脯氨酸可将前胶原(procollagen)转化为胶原蛋白,这个过程需要维生素C的参与,氧化后的维生素C在其他细胞中经蛋白二硫键异构酶(protein disulfide isomerase,PDIA)和谷氧还原酶(glutaredoxins)的催化被谷胱甘肽还原[62][63]。维生素C是一种有还原性的氧化还原催化剂,可中和诸如过氧化氢这类的活性氧物种[64]。维生素C除了有直接的抗氧化效果外,它也是还原酶抗坏血酸过氧化物酶(ascorbate peroxidase)的底物,这种酶对植物的抗逆性有特别重要的作用[65]。维生素C以较高的含量普遍存在于植物的各个部位,特别是在叶绿体中的浓度可以高达20mmol/L[66]。

谷胱甘肽

编辑谷胱甘肽是一种含有半胱氨酸的多肽,存在于多数需氧生物体内[67]。它不能从膳食中摄入而是在细胞内从相应的氨基酸合成而来[68]。由于半胱氨酸上的巯基具有还原性,能在氧化后再被还原,所以谷胱甘肽有抗氧化功能。在细胞内,谷胱甘肽在被一些代谢物和酶比如谷胱甘肽-抗坏血酸循环(Glutathione-ascorbate cycle)中的抗坏血酸盐、谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶、谷氧还蛋白氧化或直接和一些氧化性物质反应后,可被谷胱甘肽还原酶(glutathione reductase)还原恢复回还原态。鉴于它在细胞内的高浓度和在细胞氧化还原态中所扮演的中心角色,谷胱甘肽是最重要的细胞抗氧化剂之一。在一些生物体中谷胱甘肽会被其他一些含巯基的多肽所代替,比如在放线菌中被mycothiol(AcCys-GlcN-Ins)替代、在革兰氏阳性菌中被bacillithiol(Cys-GlcN-mal)替代[69][70]、在动质体中被锥虫基硫(Trypanothione)替代[71][72]。

褪黑素

编辑褪黑素是一种很强的抗氧化剂[73]。它可以轻易地穿过细胞膜和血脑屏障[74],和其他抗氧化剂不同,它不参与到还原循环(英語:redox cycling)中。像维生素C这种参与氧化还原循环中的抗氧化剂可能会起到促氧化剂的作用从而促进自由基的形成。褪黑素一旦被氧化就不能还原回去,因为氧化后的褪黑素会与自由基形成几种稳定的最终产物。因此褪黑素被称作终端抗氧化剂(英語:terminal antioxidant)[75]。

生育酚和生育三烯酚(维生素E)

编辑维生素E是由生育酚和生育三烯酚构成的8种相关化合物的统称,它们是一类具有抗氧化功能的脂溶性维生素[76][77]。在这类化合物中,由于人体优先吸收和代谢α-生育酚,所以α-生育酚的生物利用度最大,也是已经被研究的最多的[78]。

据称α-生育酚是最重要的脂溶性抗氧化剂。它清除游离的自由基中间体并且停止自由基的链增长,以此保护细胞膜免受有过氧化链反应产生的过氧化脂质的破坏[76][79],由此产生的氧化态α-生育酚自由基可被其他抗氧化剂比如维生素C、视黄醇或泛醇还原,使其重新回到活性还原态继续起到抗氧化作用[80]。相关研究发现是α-生育酚而非水溶性抗氧化剂起到有效保护缺少谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4(GPX4)的细胞避免其死亡的作用[81],而GPX4是已知的唯一一种能有效减少生物膜中过氧化脂质的酶,这一研究发现与α-生育酚的细胞膜抗氧化作用是一致。

但是还尚不清楚其他的几种维生素E在抗氧化作用中的角色和重要性[82][83]。尽管γ-生育酚作为亲核试剂可以和亲电性的诱突变物质反应[78],而生育三烯酚对于保护神经元免受损坏起到重要作用[84],但是对于除α-生育酚外的其他几种维生素E在抗氧化方面的作用仍知之甚少。

促氧化剂

编辑起到还原剂作用的抗氧化也能扮演促氧化剂(pro-oxidant)的角色。比如维生素C通过还原有氧化性的过氧化氢起到抗氧化作用[85],然而维生素C也能通过芬顿反应(Fenton reaction)先将将高价态的过渡金属离子还原,之后被还原的金属离子通过反应产生自由基[86][87]。

- 2 Fe3+ + 抗坏血酸 → 2 Fe2+ + 脱氢抗坏血酸

- 2 Fe2+ + 2 H2O2 → 2 Fe3+ + 2 OH· + 2 OH−

补充抗氧化剂对健康的潜在损害

编辑某些抗氧化剂的不适当补充会诱发疾病和增加人的死亡几率[88][89]。有假设认为,体内的自由基能诱导启动内源性反应来对抗外源的自由基(也可能是其他毒性物质)使人体受到保护[90]。最近的实验证据也有力地证实事实确实如此,内源性自由基产生的诱导作用使得秀丽隐杆线虫的寿命延长[91]。这些有毒性的自由基在低浓度时可能有毒物兴奋效应,能起到延长寿命和促进健康的效果[88][89],而补充过量的抗氧化剂则会淬灭这些对健康起到积极作用的自由基。

抗氧化酶系统

编辑概述

编辑和化学抗氧化剂的作用一样,有多种抗氧化酶相互作用所构成的网络能保护细胞免受氧化应激的损害[1][13]。比如氧化磷酸化过程释放出的过氧化物首先被转变成过氧化氢,接着被还原成水。在这个解毒过程是多种酶协同作用的结果,第一步超氧化物转变成过氧化氢的过程是在超氧化物歧化酶的催化下完成的,接着由多个不同的过氧化物酶来负责清除过氧化氢。和抗氧化代谢物在抗氧化过程中需要相互协作配合一样,在抗氧化酶的防御机制中这些酶之间也需要相互协调配合,不能单独发挥作用,这也是从研究只缺少某一种抗氧化酶的转基因小鼠的过程中认识到的[92]。

超氧化物歧化酶,过氧化氢酶和过氧化还原酶

编辑超氧化物歧化酶是一类与催化超氧化物阴离子分解产生氧气和过氧化氢密切相关的酶[93]。

过氧化氢酶是一种以铁或锰为辅助因子、可催化过氧化氢分解成水和氧气的酶[94][95]。它们存在于大多数真核生物细胞的过氧化物酶体中[96]。

过氧化还原酶(Peroxiredoxins)是一类可催化还原过氧化氢、有机过氧化物和过氧亚硝基阴离子的过氧化物酶[98]。它可分为三类:典型的2-半胱氨酸过氧化物还原酶、非典型的2-半胱氨酸过氧化物还原酶和1-半胱氨酸过氧化物还原酶[99]。

硫氧还蛋白和谷胱甘肽系统

编辑硫氧还蛋白(Thioredoxin)体系包括12千道尔顿的硫氧还蛋白和与之相伴的硫氧还蛋白还原酶[100]。

谷胱甘肽体系包括谷胱甘肽、谷胱甘肽还原酶、谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶和谷胱甘肽S-转移酶[67]。这个抗氧化酶体系存在于植物、动物和微生物中[67][101]。

疾病中的氧化应激

编辑氧化应激被认为与多种疾病例如老年痴呆症[102][103] 、帕金森氏症[104],这此病理系引发于糖尿病[105]、由糖尿病引起的并发症[105][106]、类风湿性关节炎[107]和肌萎缩性脊髓侧索硬化症引发的神经退行性变(neurodegeneration)有关[108]。对于其中的大部分疾病尚不清楚是否是由氧化剂所引发的,或者是作为这些疾病的次生后果来自一般组织的损伤。

氧化反应对DNA的损伤能引发癌症。比如超氧化歧化酶、过氧化氢酶、谷甘胱肽过氧化物酶、谷胱甘肽还原酶、谷胱甘肽S-转移酶等几种抗氧化酶能保护DNA免受氧化应激的损害。这些酶的多态性与DNA损伤有关并提高个体的癌症易感性风险。[109]

对健康的潜在影响

编辑器官功能

编辑因为大脑的新陈代谢速率很快且脑部都大量的不饱和脂质,这些脂质易成为脂质过氧化反应的目标,所以大脑非常容易受到氧化损伤的侵害[110]。抗氧化剂因此作为药物可用于治疗各类脑部损伤。超氧化物歧化酶的类似物(superoxide dismutase mimetics)[111]、丙泊酚和硫喷妥钠能被用于治疗再灌注损伤(reperfusion injury)和创伤性脑损伤(traumatic brain injury)[112]。Cerovive[113][114]和依布硒(Ebselen)[115]作为试验性药物用于中风的治疗。这些药物似乎可以避免神经元的氧化应激,并防止细胞凋亡和神经损伤。

与饮食的关系

编辑多吃水果和蔬菜的人患心脏病和一些神经疾病的风险更低[116],也有证据显示一些蔬菜和水果可能降低患癌症的风险[117]。因为水果和蔬菜是营养素和植生素的来源,由此推测抗氧化化合物可能会降低罹患一些疾病的风险。这个推断通过几种有限的方式进行了临床试验,结果显示此观点似乎不能成立,因为试验显示补充抗氧化剂对降低患某些慢性疾病比如癌症和心脏病的风险没有明显的效果[116][118]。这暗示了从食用蔬菜和水果所带来的健康益处来源于水果和蔬菜中的其他成分(比如膳食纤维)或来自一个复杂的混合成分[119]。比如富含黄酮的食物具有的抗氧化效果似乎应归功于食物中的果糖而非食物本身所含的抗氧化剂,果糖起了诱导体内增加合成抗氧化剂尿酸的作用[120]。

血液中低密度脂蛋白的氧化被认为对造成心脏病起到了作用,最初的观察研究发现摄入维生素E能降低患心脏病的风险。因此后来开展至少七个大型的临床试验来测试补充抗氧化剂维生素E的效果,补充的维生素剂量从每天50mg至每天600mg,这些试验无一结果显示维生素E的补充会对死亡总人数或因心脏病死亡的人数造成显著性差异[121]。进一步的研究也获得了同样结果[122][123]。还不清楚在这些研究中所用的或在大多数膳食补充剂中所含的维生素E剂量是否足以显著增加氧化应激[124]。总体上,尽管对氧化应激在心血管疾病中扮演的角色已有清楚的认识,但使用抗氧化剂维生素E的对照研究显示罹患心脏病的风险和已患疾病的发展速率均没有降低[125][126]。

体育锻炼

编辑在体育锻炼时,氧气的消耗量会比平时增加超过10倍[127]。耗氧量的增大会产生更多的氧化产物造成运动中和运动后的肌肉疲劳。剧烈运动后特别是在运动后的24小时内的迟发性肌肉痛也和氧化应激有关,在运动后的2至7天中免疫系统会对运动过程中出现的损伤进行修复,从而使身体素质提高。在这个过程中中性粒细胞会产生自由基用以清除受损组织[128]。因此体内过高浓度的抗氧化剂会在这个修复过程中妨碍机体的修复和适应。补充抗氧化剂也会妨碍通过体育锻炼增进健康,例如阻碍胰岛素敏感度的增加[129]。

不利影响

编辑有较强还原性的酸能起到反营养物质(antinutrient,指能阻止人体吸收和利用某些营养素的食物成分)的效果,它们会在消化系统中通过与锌、铁等结合来阻止人体吸收膳食矿物质[130]。典型的例子有草酸、单宁和植酸,它们在以植物性食物为主的饮食结构中含量很高[131]。发展中国家的饮食结构中肉类摄入较少而含有植酸的豆类和未发酵的全麦面包摄入较多,引致发展中国家的膳食中缺乏钙和铁的状况相当常见[132]。

| 食物 | 所含还原性酸 |

|---|---|

| 可可豆和巧克力、菠菜、芜菁和大黄[133] | 草酸 |

| 粗粮、玉米、豆类[134] | 植酸 |

| 茶叶、豆类、卷心菜[133][135] | 单宁 |

非极性抗氧化剂比如丁香油酚(丁香油的主要成分)有毒性限制,所以过量滥用未稀释的精油对健康不利[136]。大剂量服用水溶性抗氧化剂比如维生素C时很少考虑它们的毒性,这是因为这些化合物能通过尿液迅速排出体外[137]。大剂量服用某些抗氧化剂对健康有长期的危害影响,β-胡萝卜素和维生素A对肺癌患者的疗效试验研究发现给吸烟者大量补充含β-胡萝卜素和维生素A的物质会增加他们患肺癌的几率[138],随后的一些研究也证实了这些不良影响[139]。

食品中的抗氧化剂

编辑由于不同的抗氧化剂对各种活性氧物种的反应活性不同,所以衡量抗氧化剂的抗氧化性不是一个简单的过程。在食品科学中,抗氧化能力指数(oxygen radical absorbance capacity,ORAC)已经成为衡量食品、果汁和添加剂抗氧化能力的主要标准[140][141]。其他的一些测定方法包括Folin-Ciocalteu试剂法和等效抗氧化容量分析法(Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity assay)[142]。

包括蔬菜、水果、谷物、蛋类、肉类、豆类和坚果在内的许多食物中都含有抗氧化剂。像番茄红素和维生素C这样的抗氧化剂易在长时间的储存和烹煮下受到破坏[143][144]。相比之下其他一些抗氧化剂比如全麦谷物和茶叶等食品中含有的多酚类抗氧化剂更为稳定[145][146]。加工或烹饪食品对其中所含抗氧化剂的影响是较为复杂的,既可能增加抗氧化剂的生物利用度[147],比如蔬菜中的油溶性类胡萝卜素用油烹饪后更易被吸收利用;也可能因加工过程中暴露于空气中而使抗氧化剂受到损失[148]。

| 抗氧化化合物 | 富含抗氧化剂的食物[135][149][150] |

|---|---|

| 维生素C(抗坏血酸) | 新鲜蔬菜和水果 |

| 维生素E (生育酚, 生育三烯酚) | 植物油 |

| 多酚类抗氧化剂 (白藜芦醇, 黄酮类化合物) | 茶、咖啡、大豆、水果、橄榄油、巧克力、桂皮、牛至 |

| 类胡萝卜素(番茄红素,胡萝卜素,叶黄素) | 水果、蔬菜和蛋类[151] |

其他一些抗氧化剂无需通过食物中获取而是能够由人体自身合成。比如泛醇(ubiquinol,coenzyme Q)很难从肠道吸收获得而是由人体通过甲羟戊酸途径合成产生[43]。另一个例子是通过氨基酸在人体内合成的谷胱甘肽,因为谷胱甘肽被人体吸收前会在肠道中全部水解成游离的半胱氨酸、甘氨酸和谷氨酸,即使大剂量口服能无法提高体内谷胱甘肽的浓度[152][153]。尽管大量补充乙酰半胱氨酸可以增加谷胱甘肽[154],但没有证据显示大量摄入这类谷胱甘肽的前驱体对健康的成人有益[155]。对于治疗某些疾病比如急性呼吸窘迫症、蛋白质和热量摄入不足造成的营养不良、对乙酰氨基酚过量对肝脏造成的损伤,作为治疗手段的一部分补充这些谷胱甘肽的前体是有帮助的[154][156]。

膳食中一些其他成分作为促氧化剂可调节体内抗氧化剂水平。它们通过消耗抗氧剂比如某些抗氧化酶来降低体内抗氧化剂浓度,以此途径避免因抗氧化剂浓度过高所引起的氧化应激[157]。这些化合物比如异硫氰酸酯和姜黄素,可能也是一种可用以阻断正常细胞变为癌细胞甚至杀灭已有癌细胞的药物预防手段[157][158][159]。

抗氧化剂在其他领域的应用

编辑食品防腐剂

编辑抗氧化剂作为食品添加剂可以帮助对抗食品变质。暴露在空气和阳光下是食物氧化的两大因素,所以为此可以将食物避光保存和存放在密封容器中,或者像黄瓜那样涂蜡包裹储藏。然而,氧气对于植物的呼吸作用也是十分重要的,将植物类食品在厌氧环境下存放后会产生难闻的气味和难看的颜色[160],所以新鲜的水果和蔬菜一般都储放在含8%氧气的环境下。抗氧化剂是一类十分重要的防腐剂,不同于由细菌和真菌造成的食品变质,冰冻或冷藏食物仍然能被相对较快的氧化[161]。这些有抗氧化作用的防腐剂包括天然的维生素C和维生素和人工合成的没食子酸丙酯、TBHQ、BHT和丁基羟基茴香醚。[162][163]

不饱和脂肪酸是最常见的易被氧化的分子;氧化会引起它们的酸败[164]。由于氧化后的脂类变色并产生类似金属或硫磺的味道,所以防止富含脂肪食品的氧化是非常重要的。因此这些含脂食物很少通过风干存放,而是代之以烟熏、盐渍或发酵的方法来储藏。即使是一些脂肪较少的食物比如水果在用空气干燥之前也喷撒含硫抗氧化剂。氧化反应经常需要金属催化,这就是为何像黄油这类的脂肪从不用铝箔包裹或存放在金属容器中的原因。一些含脂食物比如橄榄油由于食物本身就含有天然抗氧化剂所以能部分避免氧化,但仍然对光氧化很敏感[165]。一些脂类化妆品比如唇膏、润肤膏也需要加入抗氧化防腐剂避免酸败。

工业用途

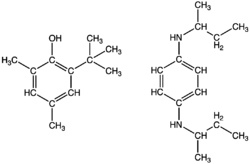

编辑抗氧化剂通常添加到工业产品中,一个常见的用途就是作为燃料和润滑剂的稳定剂防止氧化,也可加在汽油中起到防止聚合从而避免引擎积垢形成的目的[166]。2007年,工业抗氧剂的全球市场总量达到88万吨,这创造了大约37亿美元(约合24亿欧元)的收入[167]。

抗氧化剂广泛用于高分子聚合物诸如橡胶、塑料和粘合剂中,用于防止聚合物材料因氧化降解而失去强度和韧性[168]。像天然橡胶和聚丁二烯这类聚合物的分子主链中都有碳碳双键,它们特别易受氧化和臭氧化反应的破坏而发生断裂,而抗氧化剂和抗臭氧化剂(Antiozonant)则能使其受到保护。随着材料的降解和主链的断裂,固体聚合物材料外露的表面开始出现裂纹。由氧化和臭氧氧化产生的裂纹会有所区别,前者产生碎石路状的裂纹效果("crazy paving" effect),后者则是在拉伸应变的垂直方向上出现更深的裂纹。聚合物的氧化和紫外线照射下的降解经常是有关联的,主要是因为紫外线辐照会使化学键断裂产生自由基。产生的自由基与氧气反应产生过氧自由基会以链式反应的方式引起进一步的破坏。其它聚合物包括聚丙烯和聚乙烯也易受氧化的影响,前者对于氧化更为敏感是因为其主链的重复单元中存在仲碳原子,形成的自由基相比伯碳原子的自由基更为稳定,所以更易受到进攻而氧化。聚乙烯的氧化往往发生在链中的薄弱环节处,比如低密度聚乙烯中的支链点上。

| 燃料添加剂 | 成分[169] | 应用[169] |

|---|---|---|

| AO-22 | N,N'-二仲丁基对苯二胺 | 汽轮机油、变压器油、液压油、蜡和润滑油 |

| AO-24 | N,N'-二仲丁基对苯二胺 | 低温油 |

| AO-29 | 2,6-二叔丁基对甲酚 | 汽轮机油、变压器油、液压油、蜡和润滑油 |

| AO-30 | 2,4-二甲基-6-叔丁基苯酚 | 航空煤油、汽油包括航空汽油 |

| AO-31 | 2,4-二甲基-6-叔丁基苯酚 | 航空煤油、汽油包括航空汽油 |

| AO-32 | 2,4-二甲基-6-叔丁基苯酚和2,4-二甲基-6-叔丁基苯酚 | 航空煤油、汽油包括航空汽油 |

| AO-37 | 2,6-二叔丁基苯酚 | 航空煤油和汽油, 也适用于大部分航空燃油 |

参见

编辑参考资料

编辑- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Sies, Helmut. "Oxidative stress: Oxidants and antioxidants".. Experimental physiology. 1997, 82 (2): 291–5. PMID 9129943.

- ^ Werner Dabelstein, Arno Reglitzky, Andrea Schütze and Klaus Reders "Automotive Fuels" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_719.pub2

- ^ Baillie, J.K.; Thompson, A.A.R.; Irving, J.B.; Bates, M.G.D.; Sutherland, A.I.; MacNee, W.; Maxwell, S.R.J.; Webb, D.J. Oral antioxidant supplementation does not prevent acute mountain sickness: double blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. QJM. 2009, 102 (5): 341–8. PMID 19273551. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcp026.

- ^ Bjelakovic, G; Nikolova, D; Gluud, LL; Simonetti, RG; Gluud, C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007, 297 (8): 842–57. PMID 17327526. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842.

- ^ Sayin, Volkan I.; Mohamed X. Ibrahim; Erik Larsson; Jonas A. Nilsson. Antioxidants Accelerate Lung Cancer Progression in Mice 6 (221). 2014 [2015-10-15]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-22).

- ^ Jha, Prabhat; Marcus Flather; Eva Lonn; Michael Farkouh; Salim Yusuf. The Antioxidant Vitamins and Cardiovascular Disease: A Critical Review of Epidemiologic and Clinical Trial Data. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1995, 123 (11): 860–872 [2012-08-07]. (原始内容存档于2010-09-27).

- ^ Benzie, I. Evolution of dietary antioxidants. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 2003, 136 (1): 113–26. PMID 14527634. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00368-9.

- ^ Mattill, H A. Antioxidants. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1947, 16: 177–92. PMID 20259061. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.16.070147.001141.

- ^ German, JB. Food processing and lipid oxidation. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1999, 459: 23–50. ISBN 978-0-306-46051-7. PMID 10335367. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4853-9_3.

- ^ Jacob, RA. Three eras of vitamin C discovery. Sub-cellular biochemistry. 1996, 25: 1–16. PMID 8821966.

- ^ Knight, JA. Free radicals: Their history and current status in aging and disease. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 1998, 28 (6): 331–46. PMID 9846200.

- ^ Wolf, George. The discovery of the antioxidant function of vitamin E: The contribution of Henry A. Mattill. The Journal of nutrition. 2005, 135 (3): 363–6 [2012-08-07]. PMID 15735064. (原始内容存档于2017-07-07).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Davies, KJ. Oxidative stress: The paradox of aerobic life. Biochemical Society Symposia. 1995, 61: 1–31. PMID 8660387.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Vertuani, Silvia; Angusti, Angela; Manfredini, Stefano. The Antioxidants and Pro-Antioxidants Network: An Overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2004, 10 (14): 1677–94. PMID 15134565. doi:10.2174/1381612043384655.

- ^ Rhee, S. G. CELL SIGNALING: H2O2, a Necessary Evil for Cell Signaling. Science. 2006, 312 (5782): 1882–3. PMID 16809515. doi:10.1126/science.1130481.

- ^ Valko, M; Leibfritz, D; Moncol, J; Cronin, M; Mazur, M; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007, 39 (1): 44–84. PMID 16978905. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001.

- ^ Stohs, S; Bagchi, D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1995, 18 (2): 321–36. PMID 7744317. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H.

- ^ Nakabeppu, Yusaku; Sakumi, Kunihiko; Sakamoto, Katsumi; Tsuchimoto, Daisuke; Tsuzuki, Teruhisa; Nakatsu, Yoshimichi. Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis caused by the oxidation of nucleic acids. Biological Chemistry. 2006, 387 (4): 373–9. PMID 16606334. doi:10.1515/BC.2006.050.

- ^ Valko, Marian; Izakovic, Mario; Mazur, Milan; Rhodes, Christopher J.; Telser, Joshua. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2004, 266 (1–2): 37–56. PMID 15646026. doi:10.1023/B:MCBI.0000049134.69131.89.

- ^ Stadtman, E. Protein oxidation and aging. Science. 1992, 257 (5074): 1220–4. PMID 1355616. doi:10.1126/science.1355616.

- ^ Raha, S; Robinson, BH. Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000, 25 (10): 502–8. PMID 11050436. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01674-1.

- ^ Lenaz, Giorgio. The Mitochondrial Production of Reactive Oxygen Species: Mechanisms and Implications in Human Pathology. IUBMB Life. 2001, 52 (3–5): 159–64. PMID 11798028. doi:10.1080/15216540152845957.

- ^ Finkel, Toren; Holbrook, Nikki J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000, 408 (6809): 239–47. PMID 11089981. doi:10.1038/35041687.

- ^ Hirst, Judy; King, Martin S.; Pryde, Kenneth R. The production of reactive oxygen species by complex I. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2008, 36 (5): 976–80. doi:10.1042/BST0360976.

- ^ Seaver, L. C.; Imlay, JA. Are Respiratory Enzymes the Primary Sources of Intracellular Hydrogen Peroxide?. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004, 279 (47): 48742–50. PMID 15361522. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408754200.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Imlay, James A. Pathways of oxidative damage. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2003, 57: 395–418. PMID 14527285. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938.

- ^ Telfer A. Too much light? How beta-carotene protects the photosystem II reaction centre. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2005, 4 (12): 950–956. PMID 16307107. doi:10.1039/b507888c.

- ^ Küpper FC; Carpenter LJ; McFiggans GB; et al. Iodide accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008, 105 (19): 6954–8. PMC 2383960 . PMID 18458346. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709959105.

- ^ Szabó, Ildikó; Bergantino, Elisabetta; Giacometti, Giorgio Mario. Light and oxygenic photosynthesis: Energy dissipation as a protection mechanism against photo-oxidation. EMBO Reports. 2005, 6 (7): 629–34. PMC 1369118 . PMID 15995679. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400460.

- ^ Kerfeld, C. Water-soluble carotenoid proteins of cyanobacteria. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2004, 430 (1): 2–9. PMID 15325905. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.018.

- ^ Miller, RA; Britigan, BE. Role of oxidants in microbial pathophysiology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1997, 10 (1): 1–18. PMC 172912 . PMID 8993856.

- ^ Ames B, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981, 78 (11): 6858–62. PMC 349151 . PMID 6947260. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858.

- ^ Khaw, Kay-Tee; Woodhouse, Peter. Interrelation of vitamin C, infection, haemostatic factors, and cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1995, 310 (6994): 1559–63. PMC 2549940 . PMID 7787643.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Evelson, P; Travacio, M; Repetto, M; Escobar, J; Llesuy, S; Lissi, EA. Evaluation of Total Reactive Antioxidant Potential (TRAP) of Tissue Homogenates and Their Cytosols. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001, 388 (2): 261–6. PMID 11368163. doi:10.1006/abbi.2001.2292.

- ^ Morrison, John A.; Jacobsen, Donald W.; Sprecher, Dennis L.; Robinson, Killian; Khoury, Philip; Daniels, Stephen R. Serum glutathione in adolescent males predicts parental coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1999, 100 (22): 2244–7. PMID 10577998. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.100.22.2244.

- ^ Teichert, J; Preiss, R. HPLC-methods for determination of lipoic acid and its reduced form in human plasma. International journal of clinical pharmacology, therapy, and toxicology. 1992, 30 (11): 511–2. PMID 1490813.

- ^ Akiba, S; Matsugo, S; Packer, L; Konishi, T. Assay of Protein-Bound Lipoic Acid in Tissues by a New Enzymatic Method. Analytical Biochemistry. 1998, 258 (2): 299–304. PMID 9570844. doi:10.1006/abio.1998.2615.

- ^ Glantzounis, G. K.; Tsimoyiannis, E. C.; Kappas, A. M.; Galaris, D. A. Uric Acid and Oxidative Stress. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005, 11 (32): 4145–51. PMID 16375736. doi:10.2174/138161205774913255.

- ^ El-Sohemy, Ahmed; Baylin, Ana; Kabagambe, Edmond; Ascherio, Alberto; Spiegelman, Donna; Campos, Hannia. Individual carotenoid concentrations in adipose tissue and plasma as biomarkers of dietary intake. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2002, 76 (1): 172–9. PMID 12081831.

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Sowell, Anne L.; Huff, Daniel L.; Yeager, Patricia R.; Caudill, Samuel P.; Gunter, Elaine W. Retinol, alpha-tocopherol, lutein/zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, alpha-carotene, trans-beta-carotene, and four retinyl esters in serum determined simultaneously by reversed-phase HPLC with multiwavelength detection. Clinical chemistry. 1994, 40 (3): 411–6. PMID 8131277.[永久失效連結]

- ^ Stahl, W; Schwarz, W; Sundquist, AR; Sies, H. cis-trans isomers of lycopene and ?-carotene in human serum and tissues. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1992, 294 (1): 173–7. PMID 1550343. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90153-N.

- ^ Zita, ČEstmír; Overvad, Kim; Mortensen, Svend Aage; Sindberg, Christian Dan; Moesgaard, Sven; Hunter, Douglas A. Serum coenzyme Q10concentrations in healthy men supplemented with 30 mg or 100 mg coenzyme Q10 for two months in a randomised controlled study. BioFactors. 2003, 18 (1–4): 185–93. PMID 14695934. doi:10.1002/biof.5520180221.

- ^ 43.0 43.1 Turunen, Mikael; Olsson, Jerker; Dallner, Gustav. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004, 1660 (1–2): 171–99. PMID 14757233. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012.

- ^ 44.0 44.1 Enomoto, Atsushi; Endou, Hitoshi. Roles of organic anion transporters (OATs) and a urate transporter (URAT1) in the pathophysiology of human disease. Clinical and Experimental Nephrology. 2005, 9 (3): 195–205. PMID 16189627. doi:10.1007/s10157-005-0368-5.

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Wu, X.; Lee, CC; Muzny, DM; Caskey, CT. Urate Oxidase: Primary Structure and Evolutionary Implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1989, 86 (23): 9412–6. PMC 298506 . PMID 2594778. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.23.9412.

- ^ Wu, Xiangwei; Muzny, Donna M.; Chi Lee, Cheng; Thomas Caskey, C. Two independent mutational events in the loss of urate oxidase during hominoid evolution. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1992, 34 (1): 78–84. PMID 1556746. doi:10.1007/BF00163854.

- ^ Alvarez-Lario, B.; Macarron-Vicente, J. Uric acid and evolution. Rheumatology. 2010, 49 (11): 2010–5. PMID 20627967. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq204.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Watanabe, S.; Kang, DH; Feng, L; Nakagawa, T; Kanellis, J; Lan, H; Mazzali, M; Johnson, RJ. Uric Acid, Hominoid Evolution, and the Pathogenesis of Salt-Sensitivity. Hypertension. 2002, 40 (3): 355–60. PMID 12215479. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000028589.66335.AA.

- ^ Proctor, P.,Similar Functions of Uric Acid and Ascorbate in Man, Nature, vol 228,1970, p 868 [1] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Johnson, Richard J.; Andrews, Peter; Benner, Steven A.; Oliver, William. Theodore E. Woodward award. The evolution of obesity: Insights from the mid-Miocene. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2010, 121: 295–305; discussion 305–8. PMC 2917125 . PMID 20697570.

- ^ Baillie, J. K.; Bates, M. G. D.; Thompson, A. A. R.; Waring, W. S.; Partridge, R. W.; Schnopp, M. F.; Simpson, A.; Gulliver-Sloan, F.; Maxwell, S. R. J. Endogenous Urate Production Augments Plasma Antioxidant Capacity in Healthy Lowland Subjects Exposed to High Altitude. Chest. 2007, 131 (5): 1473–8. PMID 17494796. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2235.

- ^ 52.0 52.1 Hooper, DC; Scott, GS; Zborek, A; Mikheeva, T; Kean, RB; Koprowski, H; Spitsin, SV. Uric acid, a peroxynitrite scavenger, inhibits CNS inflammation, blood-CNS barrier permeability changes, and tissue damage in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. The FASEB Journal. 2000, 14 (5): 691–8. PMID 10744626.

- ^ Santos, C; Anjos, EI; Augusto, O. Uric Acid Oxidation by Peroxynitrite: Multiple Reactions, Free Radical Formation, and Amplification of Lipid Oxidation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1999, 372 (2): 285–94. PMID 10600166. doi:10.1006/abbi.1999.1491.

- ^ Scott, G. S. Therapeutic intervention in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by administration of uric acid precursors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002, 99 (25): 16303–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.212645999.

- ^ Fuhua Peng, F; Bin Zhang, B; Xiufeng Zhong, X; Jin Li, J; Guihong Xu, G; Xueqiang Hu, X; Wei Qiu, W; Zhong Pei, Z. Serum uric acid levels of patients with multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. Multiple Sclerosis. 2007, 14 (2): 188–96. PMID 17942520. doi:10.1177/1352458507082143.

- ^ Massa, Jennifer; O’Reilly, E.; Munger, K. L.; Delorenze, G. N.; Ascherio, A. Serum uric acid and risk of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology. 2009, 256 (10): 1643–8. PMC 2834535 . PMID 19468784. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-5170-y.

- ^ Amorini, Angela M.; Petzold, Axel; Tavazzi, Barbara; Eikelenboom, Judith; Keir, Geoffrey; Belli, Antonio; Giovannoni, Gavin; Di Pietro, Valentina; Polman, Chris. Increase of uric acid and purine compounds in biological fluids of multiple sclerosis patients. Clinical Biochemistry. 2009, 42 (10–11): 1001–6. PMID 19341721. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.03.020.

- ^ Becker, B. Towards the physiological function of uric acid. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1993, 14 (6): 615–31. PMID 8325534. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90143-I.

- ^ Sautin, Yuri; Johnson, Richard. Uric Acid: The Oxidant-Antioxidant Paradox. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids. 2008, 27 (6): 608–19. doi:10.1080/15257770802138558.

- ^ Smirnoff, Nicholas. L-Ascorbic acid biosynthesis. Vitamins and hormones. Vitamins & Hormones. 2001, 61: 241–66. ISBN 978-0-12-709861-6. PMID 11153268. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(01)61008-2.

- ^ Linster, Carole L.; Van Schaftingen, Emile. Vitamin C. FEBS Journal. 2007, 274 (1): 1–22. PMID 17222174. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05607.x.

- ^ Meister, Alton. Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994, 269 (13): 9397–400. PMID 8144521.

- ^ Wells, William W.; Xu, Dian Peng; Yang, Yanfeng; Rocque, Pamela A. Mammalian thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) and protein disulfide isomerase have dehydroascorbate reductase activity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990, 265 (26): 15361–4. PMID 2394726.

- ^ Padayatty, Sebastian J.; Katz, Arie; Wang, Yaohui; Eck, Peter; Kwon, Oran; Lee, Je-Hyuk; Chen, Shenglin; Corpe, Christopher; Dutta, Anand. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2003, 22 (1): 18–35. PMID 12569111.

- ^ Shigeoka, S.; Ishikawa, T; Tamoi, M; Miyagawa, Y; Takeda, T; Yabuta, Y; Yoshimura, K. Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002, 53 (372): 1305–19. PMID 11997377. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1305.

- ^ Smirnoff, Nicholas; Wheeler, Glen L. Ascorbic Acid in Plants: Biosynthesis and Function. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2000, 35 (4): 291–314. PMID 11005203. doi:10.1080/10409230008984166.

- ^ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Meister, A; Anderson, M E. Glutathione. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1983, 52: 711–60. PMID 6137189. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431.

- ^ Meister, Alton. Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988, 263 (33): 17205–8 [2012-08-10]. PMID 3053703. (原始内容存档于2020-06-10).

- ^ Gaballa A; Newton GL; Antelmann H; et al. Biosynthesis and functions of bacillithiol, a major low-molecular-weight thiol in Bacilli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107 (14): 6482–6. PMC 2851989 . PMID 20308541. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000928107.

- ^ Newton, L.; Rawat, M.; La Clair, J.; Jothivasan, K.; Budiarto, T.; Hamilton, J.; Claiborne, A.; Helmann, D.; et al. "Bacillithiol is an antioxidant thiol produced in Bacilli".. Nature chemical biology: 625–627. PMID 19578333.

- ^ Fahey, Robert C. Novelthiols Ofprokaryotes. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2001, 55: 333–56. PMID 11544359. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.333.

- ^ Fairlamb, A H; Cerami, A. Metabolism and Functions of Trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1992, 46: 695–729. PMID 1444271. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.003403.

- ^ Tan, Dun-Xian; Manchester, Lucien C.; Terron, Maria P.; Flores, Luis J.; Reiter, Russel J. One molecule, many derivatives: A never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species?. Journal of Pineal Research. 2007, 42 (1): 28–42. PMID 17198536. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x.

- ^ Reiter, Russel J.; Paredes, Sergio D.; Manchester, Lucien C.; Tan, Dan-Xian. Reducing oxidative/nitrosative stress: A newly-discovered genre for melatonin. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2009, 44 (4): 175–200. PMID 19635037. doi:10.1080/10409230903044914.

- ^ Tan, Dun-Xian; Manchester, Lucien C.; Reiter, Russel J.; Qi, Wen-Bo; Karbownik, Malgorzata; Calvo, Juan R. Significance of Melatonin in Antioxidative Defense System: Reactions and Products. Neurosignals. 2000, 9 (3–4): 137–59. PMID 10899700. doi:10.1159/000014635.

- ^ 76.0 76.1 Herrera, E.; Barbas, C. Vitamin E: Action, metabolism and perspectives. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2001, 57 (2): 43–56. PMID 11579997. doi:10.1007/BF03179812.

- ^ Packer, Lester; Weber, Stefan U.; Rimbach, Gerald. Molecular aspects of alpha-tocotrienol antioxidant action and cell signalling. The Journal of nutrition. 2001, 131 (2): 369S–73S. PMID 11160563.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Brigelius-Flohé, Regina; Traber, Maret G. Vitamin E: Function and metabolism. The FASEB Journal. 1999, 13 (10): 1145–55 [2012-08-10]. PMID 10385606. (原始内容存档于2019-12-15).

- ^ Traber, Maret G.; Atkinson, Jeffrey. Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007, 43 (1): 4–15. PMC 2040110 . PMID 17561088. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoyuan; Quinn, Peter J. Vitamin E and its function in membranes. Progress in Lipid Research. 1999, 38 (4): 309–36. PMID 10793887. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(99)00008-9.

- ^ Seiler, Alexander; Schneider, Manuela; Förster, Heidi; Roth, Stephan; Wirth, Eva K.; Culmsee, Carsten; Plesnila, Nikolaus; Kremmer, Elisabeth; Rådmark, Olof. Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Senses and Translates Oxidative Stress into 12/15-Lipoxygenase Dependent- and AIF-Mediated Cell Death. Cell Metabolism. 2008, 8 (3): 237–48. PMID 18762024. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005.

- ^ Brigelius-Flohé, Regina; Davies, Kelvin J.A. Is vitamin E an antioxidant, a regulator of signal transduction and gene expression, or a 'junk' food? Comments on the two accompanying papers: 'Molecular mechanism of α-tocopherol action' by A. Azzi and 'Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more' by M. Traber and J. Atkinson. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007, 43 (1): 2–3. PMID 17561087. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.016.

- ^ Atkinson, Jeffrey; Epand, Raquel F.; Epand, Richard M. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in membranes: A critical review. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008, 44 (5): 739–64. PMID 18160049. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.010.

- ^ Sen, Chandan K.; Khanna, Savita; Roy, Sashwati. Tocotrienols: Vitamin E beyond tocopherols. Life Sciences. 2006, 78 (18): 2088–98. PMC 1790869 . PMID 16458936. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.001.

- ^ Duarte TL, Lunec J. Review: When is an antioxidant not an antioxidant? A review of novel actions and reactions of vitamin C. Free Radic. Res. 2005, 39 (7): 671–86. PMID 16036346. doi:10.1080/10715760500104025.

- ^ Carr A, Frei B. Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions?. FASEB J. 1999, 13 (9): 1007–24 [2012-08-11]. PMID 10336883. (原始内容存档于2010-06-11).

- ^ Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 18 (2): 321–36. PMID 7744317. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H.

- ^ 88.0 88.1 Ristow, M.; Zarse, K. "How increased oxidative stress promotes longevity and metabolic health: the concept of mitochondrial hormesis (mitohormesis)".. Experimental Gerontology: 410–418. PMID 20350594. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2010.03.014.

- ^ 89.0 89.1 Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud L, Simonetti R, Gluud C. Mortality in Randomized Trials of Antioxidant Supplements for Primary and Secondary Prevention: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007, 297 (8): 842–57 [2012-08-11]. PMID 17327526. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. (原始内容存档于2010-11-12).

- ^ Tapia, P. Sublethal mitochondrial stress with an attendant stoichiometric augmentation of reactive oxygen species may precipitate many of the beneficial alterations in cellular physiology produced by caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, exercise and dietary phytonutrients: "Mitohormesis" for health and vitality. Medical Hypotheses. 2006, 66 (4): 832–43. PMID 16242247. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.09.009.

- ^ Schulz TJ, Zarse K, Voigt A, Urban N, Birringer M, Ristow M. Glucose restriction extends Caenorhabditis elegans life span by inducing mitochondrial respiration and increasing oxidative stress. Cell Metab. 2007, 6 (4): 280–93. PMID 17908557. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.011.

- ^ Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Gargano M, Cao J. The nature of antioxidant defense mechanisms: a lesson from transgenic studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106 (Suppl 5): 1219–28. JSTOR 3433989. PMC 1533365 . PMID 9788901. doi:10.2307/3433989.

- ^ Zelko I, Mariani T, Folz R. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002, 33 (3): 337–49. PMID 12126755. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00905-X.

- ^ Chelikani P, Fita I, Loewen P. Diversity of structures and properties among catalases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004, 61 (2): 192–208. PMID 14745498. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3206-5.

- ^ Zámocký M, Koller F. Understanding the structure and function of catalases: clues from molecular evolution and in vitro mutagenesis. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999, 72 (1): 19–66. PMID 10446501. doi:10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00058-3.

- ^ del Río L, Sandalio L, Palma J, Bueno P, Corpas F. Metabolism of oxygen radicals in peroxisomes and cellular implications. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992, 13 (5): 557–80. PMID 1334030. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(92)90150-F.

- ^ Parsonage D, Youngblood D, Sarma G, Wood Z, Karplus P, Poole L. Analysis of the link between enzymatic activity and oligomeric state in AhpC, a bacterial peroxiredoxin. Biochemistry. 2005, 44 (31): 10583–92. PMID 16060667. doi:10.1021/bi050448i. PDB 1YEX (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Rhee S, Chae H, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005, 38 (12): 1543–52. PMID 15917183. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026.

- ^ Wood Z, Schröder E, Robin Harris J, Poole L. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003, 28 (1): 32–40. PMID 12517450. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00003-8.

- ^ Nordberg J, Arner ES. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001, 31 (11): 1287–312. PMID 11728801. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00724-9.

- ^ Creissen G, Broadbent P, Stevens R, Wellburn A, Mullineaux P. Manipulation of glutathione metabolism in transgenic plants. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996, 24 (2): 465–9. PMID 8736785.

- ^ Christen Y. Oxidative stress and Alzheimer disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 71 (2): 621S–629S [2012-08-11]. PMID 10681270. (原始内容存档于2010-04-16).

- ^ Nunomura A, Castellani R, Zhu X, Moreira P, Perry G, Smith M. Involvement of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006, 65 (7): 631–41. PMID 16825950. doi:10.1097/01.jnen.0000228136.58062.bf.

- ^ Wood-Kaczmar A, Gandhi S, Wood N. Understanding the molecular causes of Parkinson's disease. Trends Mol Med. 2006, 12 (11): 521–8. PMID 17027339. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.09.007.

- ^ 105.0 105.1 Davì G, Falco A, Patrono C. Lipid peroxidation in diabetes mellitus. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005, 7 (1–2): 256–68. PMID 15650413. doi:10.1089/ars.2005.7.256.

- ^ Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Paolisso G. Oxidative stress and diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1996, 19 (3): 257–67. PMID 8742574. doi:10.2337/diacare.19.3.257.

- ^ Hitchon C, El-Gabalawy H. Oxidation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004, 6 (6): 265–78. PMC 1064874 . PMID 15535839. doi:10.1186/ar1447.

- ^ Cookson M, Shaw P. Oxidative stress and motor neurone disease. Brain Pathol. 1999, 9 (1): 165–86. PMID 9989458. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00217.x.

- ^ Khan MA, Tania M, Zhang D, Chen H. Antioxidant enzymes and cancer. Chin J Cancer Res. 2010, 22 (2): 87–92 [2012-10-01]. doi:10.1007/s11670-010-0087-7. (原始内容存档于2018-06-13).

- ^ Reiter R. Oxidative processes and antioxidative defense mechanisms in the aging brain (PDF). FASEB J. 1995, 9 (7): 526–33 [2012-08-12]. PMID 7737461. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2009-09-30).

- ^ Warner D, Sheng H, Batinić-Haberle I. Oxidants, antioxidants and the ischemic brain. J Exp Biol. 2004, 207 (Pt 18): 3221–31 [2012-08-12]. PMID 15299043. doi:10.1242/jeb.01022. (原始内容存档于2009-03-25).

- ^ Wilson J, Gelb A. Free radicals, antioxidants, and neurologic injury: possible relationship to cerebral protection by anesthetics. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2002, 14 (1): 66–79. PMID 11773828. doi:10.1097/00008506-200201000-00014.

- ^ Lees K, Davalos A, Davis S, Diener H, Grotta J, Lyden P, Shuaib A, Ashwood T, Hardemark H, Wasiewski W, Emeribe U, Zivin J. Additional outcomes and subgroup analyses of NXY-059 for acute ischemic stroke in the SAINT I trial. Stroke. 2006, 37 (12): 2970–8. PMID 17068304. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000249410.91473.44.

- ^ Lees K, Zivin J, Ashwood T, Davalos A, Davis S, Diener H, Grotta J, Lyden P, Shuaib A, Hårdemark H, Wasiewski W. NXY-059 for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354 (6): 588–600. PMID 16467546. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052980.

- ^ Yamaguchi T, Sano K, Takakura K, Saito I, Shinohara Y, Asano T, Yasuhara H. Ebselen in acute ischemic stroke: a placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Ebselen Study Group. Stroke. 1998, 29 (1): 12–7. PMID 9445321. doi:10.1161/01.STR.29.1.12.

- ^ 116.0 116.1 Stanner SA, Hughes J, Kelly CN, Buttriss J. A review of the epidemiological evidence for the 'antioxidant hypothesis'. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7 (3): 407–22. PMID 15153272. doi:10.1079/PHN2003543.

- ^ Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). World Cancer Research Fund (2007). ISBN 978-0-9722522-2-5.

- ^ Shenkin A. "The key role of micronutrients".. Clinical Nutrition. 2006, 25 (1): 1–13. PMID 16376462. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.006.

- ^ Cherubini A, Vigna G, Zuliani G, Ruggiero C, Senin U, Fellin R. Role of antioxidants in atherosclerosis: epidemiological and clinical update. Curr Pharm Des. 2005, 11 (16): 2017–32. PMID 15974956. doi:10.2174/1381612054065783.

- ^ Lotito SB, Frei B. Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon?. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41 (12): 1727–46. PMID 17157175. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033.

- ^ Vivekananthan DP, Penn MS, Sapp SK, Hsu A, Topol EJ. Use of antioxidant vitamins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003, 361 (9374): 2017–23. PMID 12814711. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13637-9.

- ^ Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008, 300 (18): 2123–33. PMC 2586922 . PMID 18997197. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.600.

- ^ Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: the Women's Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005, 294 (1): 56–65. PMID 15998891. doi:10.1001/jama.294.1.56.

- ^ Roberts LJ, Oates JA, Linton MF. The relationship between dose of vitamin E and suppression of oxidative stress in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43 (10): 1388–93. PMC 2072864 . PMID 17936185. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.019.

- ^ Bleys J, Miller E, Pastor-Barriuso R, Appel L, Guallar E. Vitamin-mineral supplementation and the progression of atherosclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84 (4): 880–7; quiz 954–5. PMID 17023716.

- ^ Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women's Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167 (15): 1610–8. PMC 2034519 . PMID 17698683. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.15.1610.

- ^ Dekkers J, van Doornen L, Kemper H. The role of antioxidant vitamins and enzymes in the prevention of exercise-induced muscle damage. Sports Med. 1996, 21 (3): 213–38. PMID 8776010. doi:10.2165/00007256-199621030-00005.

- ^ Tiidus P. Radical species in inflammation and overtraining. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998, 76 (5): 533–8. PMID 9839079. doi:10.1139/cjpp-76-5-533.[永久失效連結]

- ^ Ristow M, Zarse K, Oberbach A. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106 (21): 8665–70. PMC 2680430 . PMID 19433800. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903485106.

- ^ Hurrell R. Influence of vegetable protein sources on trace element and mineral bioavailability. J Nutr. 2003, 133 (9): 2973S–7S [2012-08-11]. PMID 12949395. (原始内容存档于2010-11-15).

- ^ Hunt J. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 78 (3 Suppl): 633S–639S [2012-08-11]. PMID 12936958. (原始内容存档于2009-09-07).

- ^ Gibson R, Perlas L, Hotz C. Improving the bioavailability of nutrients in plant foods at the household level. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006, 65 (2): 160–8. PMID 16672077. doi:10.1079/PNS2006489.

- ^ 133.0 133.1 Mosha T, Gaga H, Pace R, Laswai H, Mtebe K. Effect of blanching on the content of antinutritional factors in selected vegetables. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1995, 47 (4): 361–7. PMID 8577655. doi:10.1007/BF01088275.

- ^ Sandberg A. Bioavailability of minerals in legumes. Br J Nutr. 2002, 88 (Suppl 3): S281–5. PMID 12498628. doi:10.1079/BJN/2002718.

- ^ 135.0 135.1 Beecher G. Overview of dietary flavonoids: nomenclature, occurrence and intake. J Nutr. 2003, 133 (10): 3248S–3254S [2012-08-09]. PMID 14519822. (原始内容存档于2010-06-04).

- ^ Prashar A, Locke I, Evans C. Cytotoxicity of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) oil and its major components to human skin cells. Cell Prolif. 2006, 39 (4): 241–8. PMID 16872360. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00384.x.

- ^ Hornig D, Vuilleumier J, Hartmann D. Absorption of large, single, oral intakes of ascorbic acid. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1980, 50 (3): 309–14. PMID 7429760.

- ^ Omenn G, Goodman G, Thornquist M, Balmes J, Cullen M, Glass A, Keogh J, Meyskens F, Valanis B, Williams J, Barnhart S, Cherniack M, Brodkin C, Hammar S. Risk factors for lung cancer and for intervention effects in CARET, the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996, 88 (21): 1550–9. PMID 8901853. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.21.1550.

- ^ Albanes D. Beta-carotene and lung cancer: a case study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999, 69 (6): 1345S–50S [2012-08-11]. PMID 10359235. (原始内容存档于2007-03-03).

- ^ Cao G, Alessio H, Cutler R. Oxygen-radical absorbance capacity assay for antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993, 14 (3): 303–11. PMID 8458588. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90027-R.

- ^ Ou B, Hampsch-Woodill M, Prior R. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. J Agric Food Chem. 2001, 49 (10): 4619–26. PMID 11599998. doi:10.1021/jf010586o.

- ^ Prior R, Wu X, Schaich K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J Agric Food Chem. 2005, 53 (10): 4290–302. PMID 15884874. doi:10.1021/jf0502698.

- ^ Xianquan S, Shi J, Kakuda Y, Yueming J. Stability of lycopene during food processing and storage. J Med Food. 2005, 8 (4): 413–22. PMID 16379550. doi:10.1089/jmf.2005.8.413.

- ^ Rodriguez-Amaya D. Food carotenoids: analysis, composition and alterations during storage and processing of foods. Forum Nutr. 2003, 56: 35–7. PMID 15806788.

- ^ Baublis A, Lu C, Clydesdale F, Decker E. Potential of wheat-based breakfast cereals as a source of dietary antioxidants. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000, 19 (3 Suppl): 308S–311S. PMID 10875602. (原始内容存档于2009-12-23).

- ^ Rietveld A, Wiseman S. Antioxidant effects of tea: evidence from human clinical trials. J Nutr. 2003, 133 (10): 3285S–3292S [2012-08-09]. PMID 14519827. (原始内容存档于2010-08-30).

- ^ Maiani G, Periago Castón MJ, Catasta G. Carotenoids: Actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008, 53: S194–218. PMID 19035552. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200800053.

- ^ Henry C, Heppell N. Nutritional losses and gains during processing: future problems and issues. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002, 61 (1): 145–8. PMID 12002789. doi:10.1079/PNS2001142.

- ^ Antioxidants and Cancer Prevention: Fact Sheet. National Cancer Institute. [27 February 2007]. (原始内容存档于2007年3月4日).

- ^ Ortega RM. Importance of functional foods in the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9 (8A): 1136–40. PMID 17378953. doi:10.1017/S1368980007668530.

- ^ Goodrow EF, Wilson TA, Houde SC. Consumption of one egg per day increases serum lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations in older adults without altering serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. J. Nutr. 2006, 136 (10): 2519–24. PMID 16988120.

- ^ Witschi A, Reddy S, Stofer B, Lauterburg B. The systemic availability of oral glutathione. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992, 43 (6): 667–9. PMID 1362956. doi:10.1007/BF02284971.

- ^ Flagg EW, Coates RJ, Eley JW. Dietary glutathione intake in humans and the relationship between intake and plasma total glutathione level. Nutr Cancer. 1994, 21 (1): 33–46. PMID 8183721. doi:10.1080/01635589409514302.

- ^ 154.0 154.1 Dodd S, Dean O, Copolov DL, Malhi GS, Berk M. N-acetylcysteine for antioxidant therapy: pharmacology and clinical utility. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008, 8 (12): 1955–62. PMID 18990082. doi:10.1517/14728220802517901.

- ^ van de Poll MC, Dejong CH, Soeters PB. Adequate range for sulfur-containing amino acids and biomarkers for their excess: lessons from enteral and parenteral nutrition. J. Nutr. 2006, 136 (6 Suppl): 1694S–1700S. PMID 16702341.

- ^ Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J. Nutr. 2004, 134 (3): 489–92. PMID 14988435.

- ^ 157.0 157.1 Hail N, Cortes M, Drake EN, Spallholz JE. Cancer chemoprevention: a radical perspective. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45 (2): 97–110. PMID 18454943. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.004.

- ^ Pan MH, Ho CT. Chemopreventive effects of natural dietary compounds on cancer development. Chem Soc Rev. 2008, 37 (11): 2558–74. PMID 18949126. doi:10.1039/b801558a.

- ^ Yeung AWK, Tzvetkov NT, El-Tawil OS, Bungau SG, Abdel-Daim MM, Atanasov AG. Antioxidants: Scientific Literature Landscape Analysis. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2019, (2019): 8278454. doi:10.1155/2019/8278454.

- ^ Kader A, Zagory D, Kerbel E. Modified atmosphere packaging of fruits and vegetables. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1989, 28 (1): 1–30. PMID 2647417. doi:10.1080/10408398909527490.

- ^ Zallen E, Hitchcock M, Goertz G. Chilled food systems. Effects of chilled holding on quality of beef loaves. J Am Diet Assoc. 1975, 67 (6): 552–7. PMID 1184900.

- ^ Iverson F. Phenolic antioxidants: Health Protection Branch studies on butylated hydroxyanisole. Cancer Lett. 1995, 93 (1): 49–54. PMID 7600543. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(95)03787-W.

- ^ E number index. UK food guide. [5 March 2007]. (原始内容存档于2007年3月4日).

- ^ Robards K, Kerr A, Patsalides E. Rancidity and its measurement in edible oils and snack foods. A review. Analyst. 1988, 113 (2): 213–24. PMID 3288002. doi:10.1039/an9881300213.

- ^ Del Carlo M, Sacchetti G, Di Mattia C, Compagnone D, Mastrocola D, Liberatore L, Cichelli A. Contribution of the phenolic fraction to the antioxidant activity and oxidative stability of olive oil. J Agric Food Chem. 2004, 52 (13): 4072–9. PMID 15212450. doi:10.1021/jf049806z.

- ^ Boozer, Charles E.; Hammond, George S.; Hamilton, Chester E.; Sen, Jyotirindra N. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1955, 77 (12): 3233–7. doi:10.1021/ja01617a026. 缺少或

|title=为空 (帮助) - ^ Market Study: Antioxidants. Ceresana Research. [2012-08-09]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-16).

- ^ Why use Antioxidants?. SpecialChem Adhesives. [27 February 2007]. (原始内容存档于2007年2月11日).

- ^ 169.0 169.1 Fuel antioxidants. Innospec Chemicals. [27 February 2007]. (原始内容存档于2006年10月15日).

延伸阅读

编辑- Nick Lane Oxygen: The Molecule That Made the World (Oxford University Press, 2003) ISBN 0-19-860783-0

- Barry Halliwell and John M.C. Gutteridge Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine(Oxford University Press, 2007) ISBN 0-19-856869-X

- Jan Pokorny, Nelly Yanishlieva and Michael H. Gordon Antioxidants in Food: Practical Applications (CRC Press Inc, 2001) ISBN 0-8493-1222-1