甲基苯丙胺

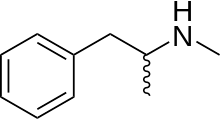

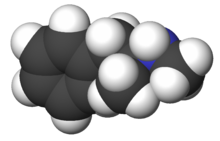

甲基苯丙胺或甲基安非他命(英语:methamphetamine,全名N-methylamphetamine[note 1]),化学式:C₆H₅CH₂CH(CH₃)NHCH₃(N-甲基-1-苯基丙-2-胺、N-甲基-α-甲基苯乙胺),其结晶形态俗称冰毒、黑话“猪肉”,是一种强效中枢神经系统兴奋剂,主要被用于毒品,较少被用于治疗注意力不足过动症和肥胖症,即便有也被当成第二线疗法[15]。甲基苯丙胺是在1893年发现,有二种对映异构:分别是左旋甲基苯丙胺(levo-methamphetamine)及右旋甲基苯丙胺(dextro-methamphetamine)。“甲基苯丙胺”一般是指左旋甲基苯丙胺及右旋甲基苯丙胺各占一半的外消旋混合物。甲基安非他命较少被医师处方,因为可能会毒害神经,以及有用作春药和欣快感促进剂等风险。而且已有疗效相同,而对人体危害风险更低的替代药物。

| |

| |

| 临床资料 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Desoxyn |

| 其他名称 | N-methylamphetamine, desoxyephedrine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| 核准状况 | |

| 依赖性 | 生理: 无 心理: 高 |

| 成瘾性 | 高 |

| 给药途径 | Medical: oral Recreational: oral, intravenous, insufflation, inhalation, suppository |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | Oral: Varies widely[1] Rectal: 99% IV: 100% |

| 血浆蛋白结合率 | Varies widely[1] |

| 药物代谢 | CYP2D6,[3] DBH[4]、FMO3,[5] XM-ligase,[6] and ACGNAT[7] |

| 生物半衰期 | 9–12 hours[2] |

| 排泄途径 | 肾 |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 537-46-2 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.882 |

| 化学信息 | |

| 化学式 | C10H15N |

| 摩尔质量 | 149.24 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| 熔点 | 3 °C(37 °F) [9] |

| 沸点 | 212 °C(414 °F) [8] at 760 mmHg |

| |

| |

甲基苯丙胺可用在非医疗用途上,会被非法交易贩售。甲基苯丙胺的非法使用在亚洲部分地区、大洋洲和美国最为普遍。在美国,消旋甲基苯丙胺、左旋及右旋甲基苯丙胺均为第二类管制药品。左旋甲基苯丙胺的吸入型鼻塞缓解剂是美国的非处方药,因此能直接在市面上购买[note 2]。在国际上,甲基安非他命名列《精神药物公约》中的第二级分类表(schedule II),因此在从事甲基安非他命的生产、散播、销售和加工等活动都被许多国家严格管制或禁止。右旋安非他命(Dextromethamphetamine)的药效比甲基苯丙胺更加强烈,但因为甲基苯丙胺的化学合成难度较低,其前体较容易取得,因此比较容易非法制造生产甲基苯丙胺。

低剂量服用甲基安非他命,会产生欣快感、提振警醒度、专注力和精神,同时会导致食欲降低、体重减轻。高剂量服用甲基安非他命则会引起中枢神经刺激剂引起的精神病、横纹肌溶解症、全身癫痫和颅内出血。 长期摄取高剂量的甲基安非他命可能加快一些不可预期且速度极快的副作用,如:心情摆荡、中枢神经刺激剂引起的精神病(譬如:偏执、幻觉、谵妄和妄想等),及具有侵略性的行为。 在娱乐用途上,甲基安非他命提升能量的效果主要体现于提振心情和增加性欲,让使用的人能连续从事性行为好几天[18]。 已知甲基安非他命能产生高度的成瘾依赖(亦即:长期使用或超高剂量使用有相当高的可能性导致使用者出现冲动用药。)和高度物质依赖(亦即:在戒除甲基安非他命时有高度的可能性会有戒断症状发生) 甲基苯丙胺的高剂量非医疗使用可能会造成急性戒断综合征,其持续时间可能会比一般的戒断时间更长。甲基苯丙胺和苯丙胺不同,甲基苯丙胺有神经毒性,会影响人类多巴胺能的神经元[19],也已证实甲基苯丙胺会伤害中枢神经系统中的血清素神经元[20][21],这些伤害包括脑部结构及功能的不良变化,例如不同脑部区域中灰质体积的减少,以及代谢整合性标志物的不良变化[21]。

甲基苯丙胺在化合物分类上属于苯乙胺衍生物及苯丙胺衍生物,和其他的二甲基苯乙胺互为结构异构,有共同的分子式:C10H15N 。

用途

编辑医用

编辑d-甲基安非他命,药品商标Desoxyn®,医疗上用于治疗注意力不足过动症(ADHD)、嗜睡症以及极端的肥胖症等。它的右旋异构体(R+异构体)可以用于治疗注意力不足过动症,但不带甲基的安非他命更常用。它的右旋异构体药品商标为“Desoxyn”,可以用于治疗嗜睡症及肥胖。当安非他命和甲基安非他命致使患者太多副作用时,Desoxyn作为次选药物。在精神方面的作用上,右旋的R(+)构型是左旋的S(-)构型的5倍[22]。

精神性毒品

编辑因其具有强效的欣快作用和催情作用[18],通常被用于娱乐,根据国家地理频道关于甲基苯丙胺的纪录片,有些派对亚文化中以性和甲基苯丙胺作为基础[18],由于其强烈的兴奋性和催情作用(对射精具有抑制作用),重复使用后可能连续几天都会发生性关系[18] 。甲基苯丙胺对精神的影响是强烈的,一段时间后会明显伴有睡眠过度的状况(白天过度嗜睡)。这些派对和游戏的亚文化流行于旧金山和纽约两大城市[18][23]。

禁忌症

编辑有以下症状的人不能使用甲基苯丙胺:曾有物质使用疾患、心血管疾病的人;严重易怒或焦虑的人;患动脉血管硬化、青光眼、甲状腺功能亢进症或严重高血压的人;[24]。

美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)表示,若以往曾对其他的兴奋剂有超敏反应,或是正在使用单胺氧化酶抑制剂,也不得使用甲基苯丙胺[24]。FDA也建议有躁郁症、重性抑郁障碍、血压偏高、有肝肾脏疾病、狂躁、思觉失调、雷诺氏综合征、癫痫发作、甲状腺问题、抽动综合征或是妥瑞症的病患,若要使用甲基苯丙胺需监控其症状[24]。因为甲基苯丙胺有可能造成生长发育迟缓,FDA也建议若用甲基苯丙胺对儿童或青少年进行治疗,需监控其身高及体重的资讯[24]。

副作用

编辑生理

编辑甲基苯丙胺在生理上造成的副作用包括:食欲不振、过动、瞳孔放大(散瞳)、过度流汗、精神运动性激动、口干及磨牙(会造成甲基苯丙胺嘴)、头痛、心律失常(可能是心跳过速或心跳过缓)、呼吸急促、高血压或低血压、体温过高、腹泻或便秘、视线模糊、头晕、肌束震颤、麻木、颤抖、皮肤干燥、痤疮及皮肤苍白或皮肤发红[25]。慢性高剂量使用的副作用有搔痒障碍、身体异常的搔痒[26]。[不可靠的医学来源]及蚁走感(感觉有昆虫在身上爬的感觉)[27]。可能会有脚抽筋之类的症状,有时会格外严重,且时间会拉长,若长期使用下,因为饮食不当以及脱水造成的电解质不平衡,此症状会格外危险[28]。

冰毒嘴

编辑甲基苯丙胺使用者和成瘾者牙齿会快速脱落[29],不管吸食毒品的方式如何都会造成此非正式命名的口腔疾病(俗称“冰毒嘴”)。注射者的状况最严重。根据美国牙科协会的说法,冰毒嘴“可能是由所导致口干症(口干),以及药物引起的心理和生理上的变化,长时间较差的口腔卫生,经常摄入高热量食物、碳酸饮料和磨牙症联合作用所致”[29][30],由于口干也是其他兴奋剂的常见副作用,而这些药物并不会直接导致严重的龋齿,许多研究人员认为甲基苯丙胺相关的龋齿更多是由于吸食者的其他因素导致。他们认为该副作用被夸大和风格化,以创造冰毒吸食者的刻板印象,以作为对新吸食者的威慑。[31]

性病的传播

编辑甲基苯丙胺的使用被发现与艾滋病阳性和未知性伴侣中无保护性交频率更高有关,这种关联在艾滋病阳性参与者中更为明显,[32]这些研究结果表明,甲基苯丙胺在未受保护的肛交中的使用和参与是共同发生的危险行为,这些行为可能会增加男同性恋和双性恋男性艾滋病病毒传播的风险。[32]使用甲基苯丙胺使男女使用者都能进行长时间的性活动,这可能导致男性生殖器疼痛和擦伤以及阴茎勃起功能障碍[33],甲基苯丙胺还可能通过磨牙症引起口腔溃疡和擦伤[33],增加了性传播感染的风险。除了性传播外通过注射器共用造成性病的传播。[34]

过量时的症状

编辑甲基苯丙胺过量时会出现许多的症状[2][24]。甲基苯丙胺中等程度的过量会有以下的症状:心律失常、意识不清、排尿疼痛、血压偏高或是偏低、高热、过度活跃和/或过度反应的反射、肌肉痛、严重精神运动性激躁、呼吸急促、颤抖、排尿犹豫以及无法排尿[2][28]。特别严重的过量会有肾上腺素风暴、甲基苯丙胺精神病、无尿症、, 心源性休克、颅内出血、循环系统崩溃、危险性的发热、肺高压、肾功能衰竭、横纹肌溶解症及血清素综合征[sources 1]。甲基苯丙胺过量会因为多巴胺激活及血清素激活的神经毒性而造成轻微的脑损伤[19][21]。甲基苯丙胺中毒死亡一般会出现在惊厥及昏迷之后[24]。

精神病症

编辑滥用甲基苯丙胺会造成兴奋剂精神病症,有许多不同的症状(例如偏执狂、幻觉、谵妄及妄想等)[2][39]。考科蓝研究有针对因滥用苯丙胺,右旋苯丙胺和甲基苯丙胺等兴奋剂造成精神病症治疗,进行的回顾研究,指出其中约有5%至15%的滥用者无法完全复原[39][40]。同一份回顾研究也指出,根据至少一次的试验,抗精神病药可以有效改善急性甲基苯丙胺精神疾病的症状[39]。

紧急治疗

编辑急性甲基苯丙胺中毒的治疗主要是在治疗其症状,治疗过程一开始可能会包括活性炭及镇静剂[2],有关血液透析或腹膜透析应用在甲基苯丙胺解毒上的效果,目前还没有足够证据来确认其是否有效[24]强制性利尿(例如透过维生素C)会增加甲基苯丙胺的排泄量,不过会增加重度酸中毒、引发癫痫或横纹肌溶解的风险,因此不建议使用[2]。高血压会有颅内出血的风险,若是严重的话,可以用注射苄胺唑啉或硝普钠来治疗[2],若提供足量苯二氮䓬类镇静剂以及提供安静的环境,血压会渐渐下降[2]。

在治疗甲基苯丙胺过量造成的躁动和精神病时,可以用氟哌啶醇等抗精神病药[41][42]。具有亲脂性及中枢神经系统渗透性的β阻断药(例如美托洛尔及拉贝洛尔)可以治疗中枢神经系统及心血管的毒性[43]。混合的α-及β-阻断药拉贝洛尔在治疗甲基苯丙胺引起的心动过速和高血压上格外有效[41],在使用β阻断药来治疗甲基苯丙胺中毒的过程,目前还没有unopposed alpha stimulation的纪录[41]。

成瘾的治疗与管理

编辑认知行为疗法是目前最有效治疗精神兴奋剂成瘾的疗法[44]。截至2014年[update],还没有有效治疗甲基苯丙胺成瘾的药物疗法[45][46][47]。甲基苯丙胺成瘾主要会透过多巴胺受体的增强活化及伏核中共定位N-甲基-D-天门冬氨酸受体(NMDA受体)来调整[note 3][49][50]。镁离子可以阻断受体钙通道,因此可以抑制NMDA受体[48][51]。

依赖及戒断症状

编辑若固定的使用甲基苯丙胺,会出现药物耐受性,若是因为非医疗的原因而使用,其耐受性会快速增强[52][53]。若是有依赖性的使用者,其戒断症状和药物耐受性的程度呈正相关[54]。甲基苯丙胺戒断产生的抑郁会持续的比可卡因戒断症状要长,其情形也较可卡因戒断症状要严重[55]。

依目前考科蓝文献回顾有关甲基苯丙胺非医疗使用者的物质依赖及药物戒断资料来看,“若慢性重度使用者突然停用[甲基苯丙胺],许多人会有时间限制的戒断症状,会在最后一次用药后24小时内出现。”[54]。慢性重度使用者的戒断症状相当常见,慢性重度使用者中有87.6%会有戒断症状,会持续三周到四周,第一周会有明显的“崩溃期”[54]。甲基苯丙胺的戒断症状包括焦虑、药物渴望、烦躁、疲劳、胃口变好、运动增加或运动减少、失去动力、失眠或是嗜睡症以及清醒梦[54]。

若孕妇使用甲基苯丙胺,其体内循环系统会有甲基苯丙胺,而且会透过胎盘传递给胎儿,婴儿也会在母乳中摄取到甲基苯丙胺[56]。甲基苯丙胺滥用的妇女所生的婴儿,考虑妊娠年龄调整后的头围数据显著较小,而且其出生重量也会较轻[56]。新生儿暴露在甲基苯丙胺下,也和其新生儿戒断症状综合征有关,其症状有激动,呕吐和呼吸加快[56]。不过此戒断症状相对较轻微,只有4%需要药物干预[55]。

化学

编辑甲基苯丙胺为人工合成,结构与苯丙胺和MDMA(摇头丸)近似,比起其他毒品,结构较简单,分子量较小。

合成过程

编辑甲基苯丙胺与甲卡西酮(methsy)、苯丙胺、以及其它兴奋剂的结构相似,可以用化学还原方法从麻黄碱或伪麻黄碱制得。大多数制备的原料属于日用品或可以从商店直接买到。因此合成甲基苯丙胺显得简单易行。在网络上可以找到许多转化合成方法,通常不大可信。最有经验的行家或求教于化学课,或从那些生产安非他命的人员那儿学来。几乎每一种方法都要用到高度危险的化学品和流程。大多数的生产方法涉及到将麻黄碱/伪麻黄碱分子中羟基的氢化。在美国最通常的方式用到红磷和碘,形成氢碘酸。另一个日渐普遍的方法是使用Birch还原法[57],用一次性锂电池中的金属锂替代金属钠(金属钠较难获得)。Birch还原法是极其危险的,因为碱金属和无水液氨都有极高的反应性。而且当加入反应物时,液氨的温度使其极易爆沸。另一种方法是苯基丙酮与甲胺的还原胺化反应(Borch还原)[58],所用的都是美国缉毒局的I级化学品。其他较不常见的方法使用其他的氢化法,比如用氢气和催化剂。

历史及各国管制政策

编辑此章节需要补充可靠的医学来源。 |

甲基苯丙胺与苯丙胺的化学结构非常相似。甲基苯丙胺是由日本化学家长井长义于1893年自麻黄碱成功合成。1919年由绪方章完成了结晶化。

冰毒的正式学名是甲基安非他命,是一种强力兴奋剂,能刺激中枢神经活动,化学结构与人体的肾上腺素类似。由于外貌上为无色的粒状透明晶体,故俗称为“冰”。冰毒在发明之初,乃是战争时期用作减低士兵劳累,非自然地提升作战能力的手段以增加其作战效率,苯丙胺还被提供给必须超长时间工作的军需厂工人使用,因而成瘾者不计其数。战后,掌握制造方法者开始自行生产并非法贩售予平民,冰毒开始被滥用,作为派对药物,其成瘾问题和害处才开始渐渐浮现。由于成瘾者向医疗机构求助的数字越来越大,令政府开始关注滥用问题,并研究对社会造成的危害。

甲基苯丙胺在第二次世界大战分别由同盟国与轴心国以Pervitin[59]之注册名称分发予前线,纳粹军广发甲基苯丙胺予士兵以作兴奋剂之用,特别是在苏德战争时的党卫队人员及德意志国防军。希特勒亦曾注射甲基苯丙胺。日本曾给士兵服用冰毒以提高战斗力。1941年武田制药与大日本制药(日本住友制药)曾出产市贩品,以及提供必须超长时间工作的军需工厂工人使用,故在日本本土、台湾、及日占区都遗留下许多成瘾患者。

1950年代,美国政府颁布法令将甲基苯丙胺规定为处方药,根据1951年出版的Arthur Grollman所著的《病理与药理学》一书,它可用于治疗嗜睡、后脑炎、帕金森综合征、酒精中毒,以及肥胖症。

1960年代,制造甲基苯丙胺的地下工厂开始普遍;1962年,冰毒首次作为一种违法毒品,被旧金山的摩托车黑帮制造出来,并在美国太平洋沿岸四处分发。这个黑帮很快便有了大批仿效者:制作冰毒所需要的原料非常普通,并且容易得到,比如外用酒精、碱液、麻黄碱和伪麻黄碱;最后一种当时作为非处方药供应。于是,作坊式实验室曾经生产了大量的违法甲基苯丙胺;墨西哥黑帮把大量廉价品带进了墨西哥。可以放进导管中抽吸的结晶甲基苯丙胺块在1980年代的夏威夷出现,并很快蔓延到美国大陆地区,成为最受欢迎的毒品种类。及至1980年,非医疗使用激增。其中,加州的圣地亚哥市更被称为北美的冰毒圣地(英国《经济学人》,1989年12月2日号)。

美国到1983年才制定法律管制持有甲基苯丙胺的前驱体和制造设备。1986年,美国制定了一份联邦管制药物取缔法,名为Federal Controlled Substance Analogue Enforcement Act,以打击“设计毒品”(designer drugs)泛滥。尽管如此,吸食甲基苯丙胺仍在美国郊区(尤其是中西部和南部)上升,直至今日。而各州都在加紧立法打击。

1991年,冰毒首次在中国被查获[60]。2008年《中华人民共和国禁毒法》颁布,在法律上正式将甲基苯丙胺纳入毒品管控。2018年甲基苯丙胺成为中国“头号毒品”[61]。

参见

编辑备注

编辑- ^ Synonyms and alternate spellings include: metamfetamine (International Nonproprietary Name (INN)), N-methylamphetamine, desoxyephedrine, Syndrox, Methedrine, and Desoxyn.[10][11][12] Common slang terms for methamphetamine include: speed, meth, crystal, crystal meth, glass, shards, ice, and tic[13] and, in New Zealand, "P".[14]

- ^ 有些美国非处方药的活化成分会列levmetamfetamine,是levomethamphetamine的INN及USAN[16][17]

- ^ NMDA受体是电压相依型配体门控离子通道,需要同时结合谷氨酸和共激动剂(D-丝氨酸或甘氨酸)来打开离子通道[48]

来源群组

编辑参考文献

编辑脚注

编辑- ^ 1.0 1.1 Methamphetamine. PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. (原始内容存档于2015-01-04) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM. The clinical toxicology of metamfetamine. Clinical Toxicology. August 2010, 48 (7): 675–694. ISSN 1556-3650. PMID 20849327. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.516752.

- ^ Adderall XR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration: 12–13. December 2013 [2013-12-30]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-07-18).

- ^ Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W. Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2013: 648. ISBN 1609133455.

Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ Krueger SK, Williams DE. Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism. Pharmacol. Ther. June 2005, 106 (3): 357–387. PMC 1828602 . PMID 15922018. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001.

- ^ butyrate-CoA ligase. BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. (原始内容存档于2017-06-22) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ glycine N-acyltransferase. BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. (原始内容存档于2017-06-23) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ Methamphetamine. PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. (原始内容存档于2015-01-04) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ Methmphetamine. Chemspider. (原始内容存档于2014-01-03) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ Methamphetamine. Drug profiles. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 2010-08-16 [2011-09-01]. (原始内容存档于2016-04-15).

- ^ Methamphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 2013-02-08. (原始内容存档于2015-12-28) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ Methedrine (methamphetamine hydrochloride): Uses, Symptoms, Signs and Addiction Treatment. Addictionlibrary.org. [2016-01-16]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-04). 参数

|newspaper=与模板{{cite web}}不匹配(建议改用{{cite news}}或|website=) (帮助) - ^ Meth Slang Names. MethhelpOnline. [2014-01-01]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-07).

- ^ Methamphetamine and the law. [2018-05-02]. (原始内容存档于2015-01-28).

- ^ Yu S, Zhu L, Shen Q, Bai X, Di X. Recent advances in methamphetamine neurotoxicity mechanisms and its molecular pathophysiology. Behav. Neurol. March 2015, 2015: 103969. PMC 4377385 . PMID 25861156. doi:10.1155/2015/103969.

In 1971, METH was restricted by US law, although oral METH (Ovation Pharmaceuticals) continues to be used today in the USA as a second-line treatment for a number of medical conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and refractory obesity [3].

- ^ Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Subchapter D – Drugs for human use. United States Food and Drug Administration. April 2015. (原始内容存档于2015-09-18) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).Topical nasal decongestants --(i) For products containing levmetamfetamine identified in 341.20(b)(1) when used in an inhalant dosage form. The product delivers in each 800 milliliters of air 0.04 to 0.150 milligrams of levmetamfetamine.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ Levomethamphetamine. Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. (原始内容存档于2014-10-06) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助).|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 San Francisco Meth Zombies (TV documentary). National Geographic Channel. August 2013 [2018-06-22]. ASIN B00EHAOBAO. (原始内容存档于2016-07-08).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. 15. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 370. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Unlike cocaine and amphetamine, methamphetamine is directly toxic to midbrain dopamine neurons.

- ^ Yu S, Zhu L, Shen Q, Bai X, Di X. Recent advances in methamphetamine neurotoxicity mechanisms and its molecular pathophysiology. Behav Neurol. 2015, 2015: 1–11. PMC 4377385 . PMID 25861156. doi:10.1155/2015/103969.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res. Rev. May 2009, 60 (2): 379–407. PMC 2731235 . PMID 19328213. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ 张建新,张大明,等。从甲基苯丙胺的对映体特征推断前体化学品。卫生研究,2009,04. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-WSYJ200904015.htm (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE. Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies 9th. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2011: 1080. ISBN 978-0-07-160593-9.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 Desoxyn Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013 [2014-01-06]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2014-01-02).

- ^ Methamphetamine Side Effects. Drugs.com. [2017-11-28]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-13).

- ^ https://addictionresource.com/drugs/crystal-meth/meth-sores/

- ^ Rusinyak, Daniel E. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Neurologic Clinics. 2011, 29 (3): 641–655. PMC 3148451 . PMID 21803215. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2011.05.004.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Westfall DP, Westfall TC. Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists. Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (编). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 12th. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2010 [2018-05-11]. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8. (原始内容存档于2013-11-10).

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Hussain F, Frare RW, Py Berrios KL. Drug abuse identification and pain management in dental patients: a case study and literature review. Gen. Dent. 2012, 60 (4): 334–345. PMID 22782046.

- ^ Methamphetamine Use (Meth Mouth). American Dental Association. [2006-12-15]. (原始内容存档于June 2008).

- ^ Hart CL, Marvin CB, Silver R, Smith EE. Is cognitive functioning impaired in methamphetamine users? A critical review. Neuropsychopharmacology. February 2012, 37 (3): 586–608. PMC 3260986 . PMID 22089317. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.276.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Halkitis PN, Pandey Mukherjee P, Palamar JJ. Longitudinal Modeling of Methamphetamine Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors in Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2008, 13 (4): 783–791. PMC 4669892 . PMID 18661225. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9432-y.

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Patrick Moore. We Are Not OK. VillageVoice. June 2005 [2011-01-15]. (原始内容存档于2011-06-04).

- ^ Methamphetamine Use and Health | UNSW: The University of New South Wales – Faculty of Medicine (PDF). [2011-01-15]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-08-16).

- ^ O'Connor PG. Amphetamines. Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals. Merck. February 2012 [2012-05-08]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-06).

- ^ Albertson TE. Amphetamines. Olson KR, Anderson IB, Benowitz NL, Blanc PD, Kearney TE, Kim-Katz SY, Wu AH (编). Poisoning & Drug Overdose 6th. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2011: 77–79. ISBN 978-0-07-166833-0.

- ^ Oskie SM, Rhee JW. Amphetamine Poisoning. Emergency Central. Unbound Medicine. 2011-02-11 [2013-06-11]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-26).

- ^ Isbister GK, Buckley NA, Whyte IM. Serotonin toxicity: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment (PDF). Med. J. Aust. September 2007, 187 (6): 361–365 [2018-05-27]. PMID 17874986. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2014-07-04).

- ^ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W. Shoptaw SJ, Ali R , 编. Treatment for amphetamine psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, (1): CD003026. PMID 19160215. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3.

A minority of individuals who use amphetamines develop full-blown psychosis requiring care at emergency departments or psychiatric hospitals. In such cases, symptoms of amphetamine psychosis commonly include paranoid and persecutory delusions as well as auditory and visual hallucinations in the presence of extreme agitation. More common (about 18%) is for frequent amphetamine users to report psychotic symptoms that are sub-clinical and that do not require high-intensity intervention ...

About 5–15% of the users who develop an amphetamine psychosis fail to recover completely (Hofmann 1983) ...

Findings from one trial indicate use of antipsychotic medications effectively resolves symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis. - ^ Hofmann FG. A Handbook on Drug and Alcohol Abuse: The Biomedical Aspects 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press. 1983: 329. ISBN 978-0-19-503057-0.

- ^ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Richards JR, Albertson TE, Derlet RW, Lange RA, Olson KR, Horowitz BZ. Treatment of toxicity from amphetamines, related derivatives, and analogues: a systematic clinical review. Drug Alcohol Depend. May 2015, 150: 1–13. PMID 25724076. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.040.

- ^ Richards JR, Derlet RW, Duncan DR. Methamphetamine toxicity: treatment with a benzodiazepine versus a butyrophenone. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. September 1997, 4 (3): 130–135. PMID 9426992. doi:10.1097/00063110-199709000-00003.

- ^ Richards JR, Derlet RW, Albertson TE. Methamphetamine Toxicity. Medscape. WebMD. [2016-04-20]. (原始内容存档于2016-04-09).

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 386. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Currently, cognitive–behavioral therapies are the most successful treatment available for preventing the relapse of psychostimulant use.

- ^ Stoops WW, Rush CR. Combination pharmacotherapies for stimulant use disorder: a review of clinical findings and recommendations for future research. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. May 2014, 7 (3): 363–374. PMC 4017926 . PMID 24716825. doi:10.1586/17512433.2014.909283.

Despite concerted efforts to identify a pharmacotherapy for managing stimulant use disorders, no widely effective medications have been approved.

- ^ Perez-Mana C, Castells X, Torrens M, Capella D, Farre M. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. September 2013, 9: CD009695. PMID 23996457. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2.

To date, no pharmacological treatment has been approved for [addiction], and psychotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment. ... Results of this review do not support the use of psychostimulant medications at the tested doses as a replacement therapy

- ^ Forray A, Sofuoglu M. Future pharmacological treatments for substance use disorders. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. February 2014, 77 (2): 382–400. PMC 4014020 . PMID 23039267. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04474.x.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 5: Excitatory and Inhibitory Amino Acids. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 124–125. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

At membrane potentials more negative than approximately −50 mV, the Mg2+ in the extracellular fluid of the brain virtually abolishes ion flux through NMDA receptor channels, even in the presence of glutamate. ... The NMDA receptor is unique among all neurotransmitter receptors in that its activation requires the simultaneous binding of two different agonists. In addition to the binding of glutamate at the conventional agonist-binding site, the binding of glycine appears to be required for receptor activation. Because neither of these agonists alone can open this ion channel, glutamate and glycine are referred to as coagonists of the NMDA receptor. The physiologic significance of the glycine binding site is unclear because the normal extracellular concentration of glycine is believed to be saturating. However, recent evidence suggests that D-serine may be the endogenous agonist for this site.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories. Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human). KEGG Pathway. 2014-10-10 [2014-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-23).

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- ^ Cadet JL, Brannock C, Jayanthi S, Krasnova IN. Transcriptional and epigenetic substrates of methamphetamine addiction and withdrawal: evidence from a long-access self-administration model in the rat. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 51 (2): 696–717. PMC 4359351 . PMID 24939695. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8776-8.

Figure 1

- ^ Nechifor M. Magnesium in drug dependences. Magnes. Res. March 2008, 21 (1): 5–15. PMID 18557129.

- ^ O'Connor, Patrick. Amphetamines: Drug Use and Abuse. Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck. [2013-09-26]. (原始内容存档于2007-02-17).

- ^ Pérez-Mañá C, Castells X, Torrens M, Capellà D, Farre M. Pérez-Mañá, Clara , 编. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9: CD009695. PMID 23996457. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2.

- ^ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Heinzerling K, Ling W. Shoptaw SJ , 编. Treatment for amphetamine withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, (2): CD003021. PMID 19370579. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003021.pub2.

The prevalence of this withdrawal syndrome is extremely common (Cantwell 1998; Gossop 1982) with 87.6% of 647 individuals with amphetamine dependence reporting six or more signs of amphetamine withdrawal listed in the DSM when the drug is not available (Schuckit 1999) ... Withdrawal symptoms typically present within 24 hours of the last use of amphetamine, with a withdrawal syndrome involving two general phases that can last 3 weeks or more. The first phase of this syndrome is the initial "crash" that resolves within about a week (Gossop 1982;McGregor 2005)

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Winslow BT, Voorhees KI, Pehl KA. Methamphetamine abuse. American Family Physician. 2007, 76 (8): 1169–1174. PMID 17990840.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Chomchai C, Na Manorom N, Watanarungsan P, Yossuck P, Chomchai S. Methamphetamine abuse during pregnancy and its health impact on neonates born at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2004, 35 (1): 228–31. PMID 15272773.

- ^ Illinois Attorney General | Basic Understanding Of Meth. Illinoisattorneygeneral.gov. [2011-01-09]. (原始内容存档于2010-09-10).

- ^ A Synthesis of Amphetamine. J. Chem. Educ. 51, 671 (1974). Erowid.org. [2011-01-09]. (原始内容存档于2010-10-17).

- ^ SID 271075 PubChem Substance Page on Methamphetamine. [2006-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-18).

- ^ 感冒药被提炼制冰毒:现实版绝命毒师在福建上演. [2023-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-11-14).

- ^ 《2018年中国毒品形势报告》发布. 中华人民共和国公安部. 2019-06-18 [2019-06-26]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-26).

书目

编辑- Methamphetamine Use: Clinical and Forensic Aspects, by Errol Yudko, Harold V. Hall,and Sandra B. McPherson. CRC Press, Boca Ratan, Fl, 2003.

- YAA BAA. Production, Traffic and Consumption of Methamphetamine in Mainland Southeast Asia", by Pierre-Arnaud CHOUVY & Joël MEISSONNIER Singapore University Press, 232 p., 2004.

- Fighting Methamphetamine in the Heartland: How Can the Federal Government Assist State and Local Efforts? (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Statement of Armand McClintock Assistant Special Agent in Charge Indianapolis District Office Drug Enforcement Administration Before the House Committee on Government Reform Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources, February 6, 2004

- Phenethylamines I Have Known And Loved: A Chemical Love Story, Alexander Shulgin and Ann Shulgin,(ISBN 978-0-9630096-0-9). a.k.a. PiHKAL. synthesis. online (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

外部链接

编辑- Second National Conference on Methamphetamine ~ Science & Response: 2007 This year's conference will once again be driven by collaboration and diversity - it will introduce the latest in methamphetamine research and innovative programming to the widest audience possible.

- A Key to Methamphetamine-Related Literature (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) This is a comprehensive thematic index of methamphetamine-related journal articles with links from citations to the corresponding PubMed abstracts.

- Life or Meth - Content Geared Towards The Gay Community (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Newsweek - "America's Most Dangerous Drug" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), see also Slate - "Meth Madness At Newsweek"

- Erowid Methamphetamine Vault (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Frontline: The Meth Epidemic(Accessed 2/15/06) (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Geopium: Geopolitics of Illicit Drugs in Asia(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Special Report on Meth in California's Central Valley (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- "New Yorker" story on the impact of widespread methamphetamine abuse Archive.is的存档,存档日期2013-01-04

- BBC story on high levels of use of methamphetamine amongst the male gay community (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Drug Enforcement Administration (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆):

- Asia & Pacific Amphetamine - Type Simulant Information Centre (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) - a very extensive information source mangaged by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- Rotten Library: Methamphetamine

- Meth In Missouri (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) A research blog on meth culture (especially in Missouri) that seeks your input- stories, comments, questions

- Montana Meth Project (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Is Meth A Plague, A Wildfire, Or the Next Katrina? ~ Reason.com (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Crystal Breaks A Chicago-area campaign addressing meth use in the gay community.

- Crystal Meth Anonymous (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) A 12-Step-based Meth Recovery group.

- Meth Strike Force (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) GALLERY and more

- met kullananlar yorumları (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)