肠胃炎

肠胃炎(英语:Gastroenteritis)是指肠胃道(胃和肠道)的炎症[8],可导致腹泻、呕吐、腹部疼痛和绞痛。[1]医生向病人解释病情时可能称之为肠胃型感冒[9]。

| 肠胃炎 Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| 又称 | Gastro, stomach bug, stomach virus, stomach flu, gastric flu, gastrointestinitis |

| |

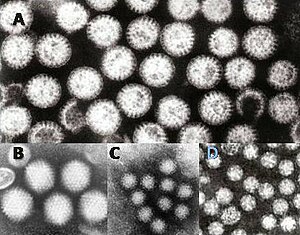

| 肠胃炎病毒: A = 轮状病毒,B = 腺病毒,C = 诺瓦克病毒和 D = 星状病毒。病毒颗粒以相同放大倍数显示,以便比较其大小。 | |

| 症状 | 腹泻、呕吐、腹痛、发热[1][2] |

| 并发症 | 脱水[2][3] |

| 类型 | 消化道疾病[*]、digestive sign[*]、疾病 |

| 病因 | 病毒、细菌、寄生、真菌[2][4] |

| 诊断方法 | 根据症状、偶尔会需要粪便培养[2] |

| 鉴别诊断 | 炎症性肠病、吸收不良综合征、乳糖不耐[5] |

| 预防 | 洗手、喝干净的水、妥善清除人类的排泄物、母乳哺育[2] |

| 治疗 | 口服液体补充 (水分 + 盐分 + 糖分)、静脉注射[2] |

| 患病率 | 24 亿 (2015)[6] |

| 死亡数 | 130万 (2015)[7] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 感染科、胃肠学 |

| ICD-11 | 1A40 |

| ICD-9-CM | 558.9 |

| DiseasesDB | 30726 |

| MedlinePlus | 000252、000254 |

| eMedicine | 775277 |

肠胃炎通常是由病毒引起[4],不过细菌、寄生虫及真菌也可致病[2][4]。在孩童中,严重肠胃炎最常见的致病原是轮状病毒[10];而在成人间会罹患此症则通常是感染诺罗病毒及曲状杆菌所致[11][12]。吃下保存不当的食物、饮用受污染的水、或是与已罹病者过度接触都有可能感染肠胃炎[2]。由于不管原因为何,此症的治疗方式通常都相同,因此通常无需对病患进行检验以确认确切致病原[2]。

预防肠胃炎的方法包括用肥皂洗手、只饮用洁净的水、适当的处理排泄物及哺喂新生儿母乳[2]。对于孩童也建议应接种轮状病毒疫苗[2][10]。若已罹病,治疗方式首为给予足够水分[2]若症状不严重,通常让病患饮用含盐及糖的水分补充品(如宝矿力)即可;若病患是喝母奶的新生儿时,则建议继续哺喂[2]。对于症状严重的患者,则需考虑以静脉注射或鼻胃管方式补充水分及营养[2][13],孩童患者同时建议为其补充锌[2]。至于抗生素部分,除非患者是孩童、且有出现高烧及血便症状时才需考虑使用,否则一般而言不必以抗生素治疗 [14][1]。

在2015年,全球有20亿人罹患肠胃炎,其中130万人因此死亡[6][7],患者以孩童与发展中国家人群为主[15]。在2011年,约有17亿的五岁以下孩童罹患肠胃炎,造成了其中约70万孩童死亡[16]。在发展中国家,两岁以下的孩童时常每年六次以上得到肠胃炎[17]。成人较少罹患肠胃炎,或许是因为成人的免疫发展较完善[18]。

症状和体征

编辑肠胃炎的主要症状是腹泻伴呕吐[18],而单独出现一种或其它症状较为少见。[1]患者也可出现腹部绞痛。[1]症状通常在受到感染后12至72小时开始。[15]病毒的感染,通常在一周到二周后才会自然痊愈。[18]病毒感染可能会导致发烧、头痛、怠倦和肌肉酸痛等症状。[18]如果有带血水泻,则大多数是受到细菌感染[18],而且可能会引发剧烈的腹痛,症状通常会持续数周。[19]

大部分受到轮状病毒感染的儿童都会在3至8天内康复。[20]在贫困的国家,严重的感染个案因为缺乏治疗,所以腹泻经常持续.[21],脱水是腹泻的常见并发症。[22]严重脱水的儿童可能出现微血管回充延迟、皮肤弹性(skin turgor)变差及腹式呼吸。[23]在卫生环境欠佳的地区,重复感染导致营养不良[15],发育和智商成长都出现障碍。其他的病毒感染则可能导致幼儿痉挛症状。[1] 弯曲杆菌感染的并发症包括 1% 会患上反应性关节炎和0.1%会出现格林-巴利综合征,自下向上蔓延的麻痹症状。大肠杆菌和赤痢菌分泌志贺毒素,引发溶血性尿毒综合征[24];以致肾功能不良、血小板计数低、红细胞计数低(由其破坏所致)。[24]儿童比成年人较多出现溶血性尿毒综合征。[17]某些病毒感染可导致良性婴儿抽搐。[1]

病因

编辑病毒(特别是轮状病毒)及以大肠杆菌和弯曲杆菌为代表的细菌是肠胃炎的主要病因。[25][15]但也有大量其它病原可导致该病。[17]有时可观察到非感染性的病因,但其发生率明显低于细菌和病毒的致病源。[1]儿童由于缺乏免疫力和相对较差的卫生,感染的风险较高。[1]

病毒感染

编辑经常导致肠胃炎的病毒包括轮状病毒、诺瓦克病毒、腺病毒和星状病毒。[18][26]轮状病毒是导致儿童肠胃炎的主要原因,[25],而且遍及全球,不分贫富。[20]70% 儿童肠胃炎都是因为受到病毒侵袭.[13],但大部分成年人则因为曾经接触过轮状病毒,所以有免疫能力。[27] 北美洲成年人患上的肠胃炎,90%是因为诺沃克病毒感染,[18]该局部流行病多数发生在人多聚集的环境,例如游轮、[18]、医院、和人多挤迫的食堂[1]。即使腹泻过后,病人仍然会继续排放病毒。[18]诺沃克病毒感染约占10%的儿童肠胃炎。[1]

细菌感染

编辑在发展中的地区,空肠弯曲菌是最常见的肠胃炎细菌,半数和接触家禽有关连。[19]儿童的肠胃炎之中,细菌感染占15%;最常见的细菌包括大肠杆菌、沙门氏菌、志贺菌和空肠弯曲菌。[13]受到细菌污染的食物,如果继续留在室温内数个小时,细菌就会继续繁殖。如果进食污染的食物,感染的风险机会就会增加。[17]曾被发现带菌的蔬果和食物包括未煮熟的鲜肉、鸡、海产、蛋、成长中的芽菜、未经消毒的牛奶、软起司、果菜汁。[28]在发展中国家,特别是非洲和撒哈拉沙漠边缘,霍乱是肠胃炎的常见病因,该病常经污水和污脏的食物传播和肆虐。[29]

细菌分泌的毒素亦可能导致腹部不适和腹泻。 艰难梭菌经常出现在年长人士的肠胃炎案例之中。[17]幼儿可能会带菌但没有症状。[17]曾经住过医院和服用抗生素就会增加受到感染的机会。[30] 金黄色葡萄球菌 感染型腹泻亦可见于使用了抗生素的患者中。 [31] "旅行者腹泻"通常是因为受到细菌感染。 服用压抑胃酸的药物,亦会增加受到困难梭菌、沙门氏菌、和弯曲杆菌感染的机会 [32],而服用质子泵抑制剂类胃药患者腹泻的风险比H2受体抑制剂更高。[32]

寄生虫感染

编辑多种原生动物可导致肠胃炎 – 最常见的是兰氏贾第鞭毛虫,而阿米巴变形虫和隐孢子虫感染也有报道[13],最常见的感染途径是根据受污染的水源传播。作为一类病原,它们约占儿童肠胃炎成因的10%。[24]鞭毛虫感染较多出现在发展中的国家,但仍遍及全球。[33]。[33]

传染

编辑传染会通过饮用被污染的水,或者共同使用一些私人物品而发生。[15]在一些有干湿两季的地区,水质会在雨季变得很差,这与传染病的爆发也有关。[15]在四季分明的地区,感染则多发于冬季。[17]而在全球范围内,使用没有正确消毒的奶瓶喂奶是婴儿感染的一个重要原因。[15]传染率通常与糟糕的卫生条件有关,特别是在那些已经存在营养不良并且居住环境拥挤简陋[34]的孩子之间[18][17]。一旦产生抗药性,成年人会毫无任何症状地携带这种致病因子,因此也就成了一个传染源的天然载体。[17]尽管一些病菌(例如志贺菌病)的传染只发生在灵长类动物,但是许多的致病微生物却会在各种动物之间相互传播(比如贾第虫)。[17]

非感染性

编辑非传染性的胃肠炎也有很多因素造成。[1]一些较常见的原因包括: 药物(像非甾体抗炎药), 一些食物例如乳糖(在那些无法耐受饿的人群中),和 麸质(在那些患有乳糜泻)。克隆氏症也属于非传染性疾病来源(通常很严重的)肠胃炎。[1]疾病是仅次于毒素的造成恶心,呕吐的原因,腹泻的食物包括:食用毒性鱼肉,或食用被污染的鱼类造成,例如:食用变质的鲭鱼、食用河豚造成河豚毒素中毒,以及肉毒杆菌中毒这通常是食物保存不正确所致。[35]

病理生理学

编辑肠胃炎被定义为小肠或者大肠感染而导致的呕吐或腹泻。[17]小肠的改变通常是非炎症性的,然而大肠的变化往往是炎症性的。[17]造成感染的病原体的数量也不同,从少到一个(对于隐孢子虫)到多至108个(对于霍乱弧菌)。[17]

诊断

编辑肠胃炎的临床诊断通常基于病人的病症和症状。[18]通常确定确切的病因是没有必要的,因为它并不影响对于疾病的处理方法。[15] 然而,对于那些便血和那些可能已经食物中毒,或者那些近期到过发展中国家旅游的人来说,粪便培养是应当实施的。[13]一些诊断性检查化验对于检测病情也是很有必要的。[18]因为几乎10%的婴儿和儿童会并发低血糖,因此推荐在这一群体中实施血清葡萄糖测定。[23]电疗学和肾脏功能也应该进行检测。[13]

脱水

编辑脱水是该类评估中一个非常重要的项目,通常分为轻微(3–5%),中等(6–9%),和严重(≥10%)几种情况。[1]在儿童之中,最精准的中度和重度脱水的信号是持久的毛细血管充血,较差的皮肤饱满度,和呼吸异常。[23][36]一些其他有用的发现(当结合使用的时候)包含活跃度降低,无泪,口干等。[1]排尿量和唾液分泌量正常则不需担心。[23]实验室的测试对临床的判断脱水状态并无太大帮助[1]

鉴别诊断

编辑其他应该排除的可能导致跟肠胃炎类似症状的疾病有:阑尾炎,肠扭转,炎症性肠病,尿路感染和糖尿病。[13]胰腺功能不全,短肠综合征,惠普尔病,乳糜泻和轻泻药滥用等因素也要考虑在内。[37]当病人只是出现呕吐,或者单独出现腹泻的时候,这时的鉴别诊断某种程度上说就会变得很复杂。[1]

阑尾炎会表现出呕吐,腹痛,在大约33%病例中还会表现少量腹泻。[1]这刚好与肠胃炎表现出来的大量腹泻相反。[1]儿童发生肺部感染或者尿路感染同样会导致呕吐和腹泻。[1]经典的糖尿病酮症酸中毒(DKA)通常表现为腹痛、恶心和呕吐,但没有腹泻。[1]一项调查发现有17%的患有经典糖尿病酮症酸的孩子最初被诊断为肠胃炎.[1]

预防

编辑生活方式

编辑良好的未被污染饮用水供应和好的卫生设备对于降低肠胃炎的感染比例和临床病例是十分重要的。[17]同时,研究还发现,无论发达国家还是发展中国家,个人的一些方法(比如洗手),都至少能使肠胃炎的发生率或者患病率降低30%。[23]使用酒精凝胶清洗液效果更佳。[23] 哺乳是很重要的,作为一种对于卫生条件的提升是非常重要的,特别是在一些卫生条件很差的地区。[15]母乳喂养既可以降低肠胃炎的发生率也可以缩短其持续时间。[1]与此同时,避免食物和水的污染也是(预防胃肠炎发生)有效的方法。[38]

接种

编辑为了保证疫苗接种的效果和安全性,在2009年,世界卫生组织呼吁全球范围内对儿童实施轮状病毒疫苗接种。[39][25]两种商业疫苗已经面世,而且还有更多的正在开发。[39]在非洲和亚洲,这些疫苗的使用已经大大减少了婴儿[39] 患重病的几率,而且那些推行了国家免疫计划的国家在疾病发生率和严重程度上已经有了明显下降。[40][41]而且这些疫苗通过减少交叉传染也可以保护未接种疫苗的儿童。[42]从2000年以来,轮状病毒疫苗接种工程在美国的开展已经大体减少了80%的腹泻病例。[43][44][45]第一剂疫苗注射对象为6-15周大的婴儿。[25]而口服霍乱菌苗最近两年也已经证实其有效率达50-60%。[46]

处理

编辑通常,肠胃炎是一个急性并带有自控力的疾病,且通常不需要药物治疗。[22]当前更受青睐的,用于温和地缓解在那些轻微到中等脱水的方法是口服补液疗法(ORT)。[24]灭吐灵和/或枢复宁可能对一些孩子有用,[47]而丁基东莨菪碱则可用于治疗腹痛。[48]

补充水分

编辑对于儿童和成人肠胃炎的基本处理方法是水分补充。而经口补水疗法的出现更好地实现了这一点,虽然当患者意识水平下降或者脱水相当严重时,静脉注射是必要的程序。但口服补水疗法仍是一种很好的补水方法。[49][50]口服替代疗法产品之中,使用碳水化合物(即小麦或米)的食(饮)品优先于富含单糖的食(饮)品。[51]富含单糖的饮料,例如汽水,果汁等,不建议给5岁以下的孩子使用,因为它们可能会加重腹泻。[22]如果没有特效的口服补液剂或者味道较差,白开水也是可以使用的。[22]如有适应症,亦可在儿童身上使用鼻胃管来补充流质。[13]

膳食

编辑母乳喂养的婴儿建议以平时的喂养方法继续,配方奶喂养的婴儿在ORT补液后立即继续配方喂养。[52]通常不需要改为无乳糖或低乳糖配方。[52]发生腹泻时,儿童应进食与平常相同的饭食,但应避免高单糖的食物。[52]BRAT餐(香蕉、米饭、苹果酱、烤面包和茶)已不再是推荐饮食,因为它不包含足够的养分,并且相对平常饮食并无优点。[52]一些益生菌已被证明有利于减少腹泻的延续时间和大便的次数,[53]并且在预防和治疗抗生素相关性的腹泻上也许有用。[54]类似的,发酵的乳类产品(如 酸奶)等也同样有益。[55]补锌在发展中世界儿童腹泻的预防及治疗上似乎有效。[56]

止吐药

编辑止吐药物可能有助于治疗小儿呕吐。昂丹司琼有一定实用,单次使用即可减少静脉输液需求、住院需求及呕吐。[57][58][59]胃复安也可能有效。[59]但是昂但司琼的使用可能与小儿再次入院几率增加有关。[60]如果临床上需要,昂丹司琼的静脉液也可以口服。[61]茶苯海明虽然能减少呕吐,但临床效用似乎并不大。[1]

抗生素

编辑抗生素通常不用在肠胃炎治疗,但如果症状特别严重时[62]或在找到了易感细菌、怀疑某细菌感染的情况下是建议使用的。[63]如果要使用抗生素,则大环内酯类(如阿奇霉素)优于氟喹诺酮类药物,因为后者抗药性较高。[19]伪膜性肠炎通常由使用抗生素引起,治疗方法为中断病源及用甲硝唑或万古霉素治疗。[64]可治疗的细菌和原虫包括志贺杆菌[65] Salmonella typhi,[66]和贾第鞭毛虫等。[33]在贾第鞭毛虫或痢疾阿米巴感染时,替硝唑优于甲硝唑,是首选治疗药物。[67][33]世界卫生组织(WHO)建议对同时有便血和发烧的小儿应使用抗生素。[1]

止泻药物

编辑止泻药物在理论上有并发症的风险,虽然临床经验表明这种可能性不大,[37]在便血或伴有发烧的腹泻情况下不建议使用。[68]洛哌丁胺是一种阿片类似物,常用于腹泻的对症治疗。[69]但是洛派丁胺不适于用于儿童,因为此药物可能会穿越儿童尚未成熟的血脑屏障,引起中毒。水杨酸亚铋是一种不溶的三价铋和水杨酸复合物,可以在轻至中度病例中使用,[37]但在理论上水杨酸中毒是可能的。[1]

传染病学

编辑| 无数据 ≤500 500–1000 1000–1500 1500–2000 2000–2500 2500–3000 | 3000–3500 3500–4000 4000–4500 4500–5000 5000–6000 ≥6000 |

据计全球每年有三亿到五亿胃肠炎病例,[70]主要发生于发展中世界的儿童中。[15]在2008年有1.3亿五岁以下儿童死于胃肠炎,[71]大多数这些死亡病例发生在世界上最贫穷的国家中。[17]这些死亡病例中有多于45万是患小儿轮状病毒的5岁以下的幼童。[72][73]每年有三百万到五百万霍乱病例,引起10万病例死亡。[29]在发展中国家的两岁以下儿童常每年感染六次或更多临床意义上的胃肠炎。[17]成年人的感染较为少见,部分原因是后天获得的免疫。[18]

在1980年,由各种原因导致的肠胃炎造成了460万儿童的死亡,绝大多数发生在发展中国家。[64]到2000年,死亡率明显减少(每年约150万人死亡),主要是由于口服补液治疗的引进和广泛使用。[74]在美国,引起肠胃炎的感染是名列第二的最常见的感染(仅次于普通感冒),每年引起2亿到3.75亿急性腹泻[18][17]及大约一万死亡病例,[17]其中有150到300起死亡病例发生在五岁以下的儿童中。[1]

历史

编辑“肠胃炎”这一词语的第一次使用是在1825年。[75]在此之前,胃肠炎被称为伤寒、“霍乱寒”,或其他名称,又或含糊地被称为“肠绞痛”、“surfeit”,“flux”,“colic”,“bowel complaint”,或急性腹泻的许多旧称之一。[76]

社会及文化

编辑胃肠炎有许多口语化的名称,如“墨西哥毒针”、“拉德里肚”、“旅游病”、“后门跑”等等。[17]它在很多军队宣传占一席之地,并被认为是英文俗语“no guts no glory”(没有勇气就没有荣耀;guts 意为肚子,也指勇气)的来源。[17]

在美国[1]每年有370万看诊的主要原因是胃肠炎,在法国这个数字是3百万。[77]据信胃肠炎每年在美国造成的损失有23亿美元,[78]仅由轮状病毒引起的损失每年就有1亿美元。[1]

研究

编辑有一定数量的胃肠炎疫苗正在研发中。例如全球肠胃炎的首要病源之首,志贺菌和肠毒素“大肠埃希氏大肠杆菌”(ETEC)的疫苗。[79][80]

其他动物中的肠胃炎

编辑许多引起猫狗肠胃炎的病源与人类病源相同。最常见的生物病源为:空肠弯曲菌、艰难梭菌、产气荚膜梭菌和沙门氏菌。[81]大量有毒植物也可能会导致胃肠症状。[82]一些病源对某些物种有针对性。猪传染性胃肠炎冠状病毒(猪传染性胃肠炎TGEV)造成猪的呕吐、腹泻和脱水。[83]据信是由野生鸟传播,并没有特殊的治疗办法。[84]此病不会传播给人类。[85]

参考文献

编辑引用

编辑- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 Singh, Amandeep. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Practice Acute Gastroenteritis — An Update. Emergency Medicine Practice. July 2010, 7 (7) [2013-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2019-12-11).

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Ciccarelli, S; Stolfi, I; Caramia, G. Management strategies in the treatment of neonatal and pediatric gastroenteritis.. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2013-10-29, 6: 133–61. PMC 3815002 . PMID 24194646. doi:10.2147/IDR.S12718.

- ^ Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2015: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014: 479. ISBN 9780323084307. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 A. Helms, Richard. Textbook of therapeutics : drug and disease management 8. Philadelphia, Pa. [u.a.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006: 2003. ISBN 9780781757348. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ Caterino, Jeffrey M.; Kahan, Scott. In a Page: Emergency medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2003: 293. ISBN 9781405103572 (英语).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.. Lancet. 2016-10-08, 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMID 27733282.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.. Lancet. 2016-10-08, 388 (10053): 1459–1544. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Schlossberg, David. Clinical infectious disease Second. 2015: 334. ISBN 978-1-107-03891-2. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ 李佳欣. 什麼是「腸胃型感冒」? 1張表區分感冒還是腸胃炎 - 康健雜誌. 康健杂志 第155期. 2011-10-01 [2021-02-26].

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. February 2012, 12 (2): 136–41. PMID 22030330. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5.

- ^ Marshall JA, Bruggink LD. The dynamics of norovirus outbreak epidemics: recent insights. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. April 2011, 8 (4): 1141–9. PMC 3118882 . PMID 21695033. doi:10.3390/ijerph8041141.

- ^ Man SM. The clinical importance of emerging Campylobacter species. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. December 2011, 8 (12): 669–85. PMID 22025030. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.191.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Webb, A; Starr, M. Acute gastroenteritis in children.. Australian family physician. 2005 Apr, 34 (4): 227–31. PMID 15861741.

- ^ Zollner-Schwetz, I; Krause, R. Therapy of acute gastroenteritis: role of antibiotics.. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. August 2015, 21 (8): 744–9. PMID 25769427. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.002.

- ^ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 Webber, Roger. Communicable disease epidemiology and control : a global perspective 3rd. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: Cabi. 2009: 79 [2013-08-25]. ISBN 978-1-84593-504-7. (原始内容存档于2013-12-26).

- ^ Walker, CL; Rudan, I; Liu, L; Nair, H; Theodoratou, E; Bhutta, ZA; O'Brien, KL; Campbell, H; Black, RE. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea.. Lancet. 2013-04-20, 381 (9875): 1405–16. PMID 23582727. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6.

- ^ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 17.14 17.15 17.16 17.17 17.18 17.19 Mandell 2010 Chp.93

- ^ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 Eckardt AJ, Baumgart DC. Viral gastroenteritis in adults. Recent Patents on Anti-infective Drug Discovery. January 2011, 6 (1): 54–63. PMID 21210762.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Galanis, E. Campylobacter and bacterial gastroenteritis.. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 2007-09-11, 177 (6): 570–1. PMC 1963361 . PMID 17846438. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070660.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Meloni, A; Locci, D, Frau, G, Masia, G, Nurchi, AM, Coppola, RC. Epidemiology and prevention of rotavirus infection: an underestimated issue?. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2011 Oct,. 24 Suppl 2: 48–51. PMID 21749188. doi:10.3109/14767058.2011.601920.

- ^ Toolkit. DefeatDD. [2012-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2012年4月27日).

- ^ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Management of acute diarrhoea and vomiting due to gastoenteritis in children under 5. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. April 2009 [2013-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-21).

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Tintinalli, Judith E. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. 2010: 830–839. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Elliott, EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children.. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2007-01-06, 334 (7583): 35–40. PMC 1764079 . PMID 17204802. doi:10.1136/bmj.39036.406169.80.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Szajewska, H; Dziechciarz, P. Gastrointestinal infections in the pediatric population.. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2010 Jan, 26 (1): 36–44. PMID 19887936. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333d799.

- ^ Dennehy PH. Viral gastroenteritis in children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. January 2011, 30 (1): 63–4. PMID 21173676. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3182059102.

- ^ Desselberger U, Huppertz HI. Immune responses to rotavirus infection and vaccination and associated correlates of protection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. January 2011, 203 (2): 188–95. PMC 3071058 . PMID 21288818. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiq031.

- ^ Nyachuba, DG. Foodborne illness: is it on the rise?. Nutrition Reviews. 2010 May, 68 (5): 257–69. PMID 20500787. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00286.x.

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Charles, RC; Ryan, ET. Cholera in the 21st century.. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2011 Oct, 24 (5): 472–7. PMID 21799407. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a88af.

- ^ Moudgal, V; Sobel, JD. Clostridium difficile colitis: a review.. Hospital practice (1995). 2012 Feb, 40 (1): 139–48. PMID 22406889. doi:10.3810/hp.2012.02.954.

- ^ Lin, Z; Kotler, DP; Schlievert, PM; Sordillo, EM. Staphylococcal enterocolitis: forgotten but not gone?. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2010 May, 55 (5): 1200–7. PMID 19609675.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Leonard, J; Marshall, JK, Moayyedi, P. Systematic review of the risk of enteric infection in patients taking acid suppression.. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007 Sep, 102 (9): 2047–56; quiz 2057. PMID 17509031. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01275.x.

- ^ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Escobedo, AA; Almirall, P, Robertson, LJ, Franco, RM, Hanevik, K, Mørch, K, Cimerman, S. Giardiasis: the ever-present threat of a neglected disease.. Infectious disorders drug targets. 2010 Oct, 10 (5): 329–48. PMID 20701575.

- ^ Grimwood, K; Forbes, DA. Acute and persistent diarrhea.. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2009 Dec, 56 (6): 1343–61. PMID 19962025. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.004.

- ^ Lawrence, DT; Dobmeier, SG; Bechtel, LK; Holstege, CP. Food poisoning.. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2007 May, 25 (2): 357–73; abstract ix. PMID 17482025. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.02.014.

- ^ Steiner, MJ; DeWalt, DA, Byerley, JS. Is this child dehydrated?. JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004-06-09, 291 (22): 2746–54. PMID 15187057. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746.

- ^ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Warrell D.A., Cox T.M., Firth J.D., Benz E.J. (编). The Oxford Textbook of Medicine 4th. Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-19-262922-0. (原始内容存档于2012-03-21).

- ^ Viral Gastroenteritis. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. February 2011 [2012-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2012年4月24日).

- ^ 39.0 39.1 39.2 World Health Organization. Rotavirus vaccines: an update (PDF). Weekly epidemiological record. December 2009, 51–52 (84): 533–540 [2012-05-10]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-07-09).

- ^ Giaquinto, C; Dominiak-Felden G, Van Damme P, Myint TT, Maldonado YA, Spoulou V, Mast TC, Staat MA. Summary of effectiveness and impact of rotavirus vaccination with the oral pentavalent rotavirus vaccine: a systematic review of the experience in industrialized countries. Human Vaccines. 7. July 2011, 7: 734–748 [2012-05-10]. PMID 21734466. doi:10.4161/hv.7.7.15511. (原始内容存档于2013-02-17).

- ^ Jiang, V; Jiang B, Tate J, Parashar UD, Patel MM. Performance of rotavirus vaccines in developed and developing countries. Human Vaccines. July 2010, 6 (7): 532–542 [2012-05-10]. PMID 20622508. (原始内容存档于2013-02-17).

- ^ Patel, MM; Steele, D, Gentsch, JR, Wecker, J, Glass, RI, Parashar, UD. Real-world impact of rotavirus vaccination.. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011 Jan, 30 (1 Suppl): S1–5. PMID 21183833. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefa1f.

- ^ US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Delayed onset and diminished magnitude of rotavirus activity—United States, November 2007 – May 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008, 57 (25): 697–700 [2012-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2012-06-08).

- ^ Reduction in rotavirus after vaccine introduction—United States, 2000–2009. MMWR Morb.Mortal.Wkly.Rep. October 2009, 58 (41): 1146–9 [2013-08-25]. PMID 19847149. (原始内容存档于2009-10-31).

- ^ Tate, JE; Cortese, MM, Payne, DC, Curns, AT, Yen, C, Esposito, DH, Cortes, JE, Lopman, BA, Patel, MM, Gentsch, JR, Parashar, UD. Uptake, impact, and effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in the United States: review of the first 3 years of postlicensure data.. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011 Jan, 30 (1 Suppl): S56–60. PMID 21183842. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefdc0.

- ^ Sinclair, D; Abba, K, Zaman, K, Qadri, F, Graves, PM. Oral vaccines for preventing cholera.. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2011-03-16, (3): CD008603. PMID 21412922. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008603.pub2.

- ^ Alhashimi D, Al-Hashimi H, Fedorowicz Z. Alhashimi, Dunia , 编. Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, (2): CD005506. PMID 19370620. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005506.pub4.

- ^ Tytgat GN. Hyoscine butylbromide: a review of its use in the treatment of abdominal cramping and pain. Drugs. 2007, 67 (9): 1343–57. PMID 17547475.

- ^ BestBets:Fluid Treatment of Gastroenteritis in Adults. [2013-08-25]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-17).

- ^ Canavan A, Arant BS. Diagnosis and management of dehydration in children. Am Fam Physician. October 2009, 80 (7): 692–6. PMID 19817339.

- ^ Gregorio GV, Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG. Gregorio, Germana V , 编. Polymer-based oral rehydration solution for treating acute watery diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, (2): CD006519. PMID 19370638. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006519.pub2.

- ^ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS, Duggan C. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Recomm Rep. November 2003, 52 (RR-16): 1–16 [2016-11-04]. PMID 14627948. (原始内容存档于2014-10-28).

- ^ Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF. Allen, Stephen J , 编. Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, 11 (11): CD003048. PMID 21069673. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub3.

- ^ Hempel, S; Newberry, SJ; Maher, AR; Wang, Z; Miles, JN; Shanman, R; Johnsen, B; Shekelle, PG. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis.. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012-05-09, 307 (18): 1959–69. PMID 22570464.

- ^ Mackway-Jones, Kevin. Does yogurt decrease acute diarrhoeal symptoms in children with acute gastroenteritis?. BestBets. June 2007 [2016-11-04]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-17).

- ^ Telmesani, AM. Oral rehydration salts, zinc supplement and rota virus vaccine in the management of childhood acute diarrhea.. Journal of family and community medicine. 2010 May, 17 (2): 79–82. PMC 3045093 . PMID 21359029. doi:10.4103/1319-1683.71988.

- ^ DeCamp LR, Byerley JS, Doshi N, Steiner MJ. Use of antiemetic agents in acute gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. September 2008, 162 (9): 858–65. PMID 18762604. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.9.858.

- ^ Mehta S, Goldman RD. Ondansetron for acute gastroenteritis in children. Can Fam Physician. 2006, 52 (11): 1397–8 [2016-11-04]. PMC 1783696 . PMID 17279195. (原始内容存档于2020-05-30).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 Fedorowicz, Z; Jagannath, VA, Carter, B. Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents.. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2011-09-07, 9 (9): CD005506. PMID 21901699. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005506.pub5.

- ^ Sturm JJ, Hirsh DA, Schweickert A, Massey R, Simon HK. Ondansetron use in the pediatric emergency department and effects on hospitalization and return rates: are we masking alternative diagnoses?. Ann Emerg Med. May 2010, 55 (5): 415–22. PMID 20031265. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.011.

- ^ Ondansetron. Lexi-Comp. May 2011 [2016-11-04]. (原始内容存档于2012-06-06).

- ^ Traa BS, Walker CL, Munos M, Black RE. Antibiotics for the treatment of dysentery in children. Int J Epidemiol. April 2010, 39 (Suppl 1): i70–4. PMC 2845863 . PMID 20348130. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq024.

- ^ Grimwood K, Forbes DA. Acute and persistent diarrhea. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. December 2009, 56 (6): 1343–61. PMID 19962025. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.004.

- ^ 64.0 64.1 Mandell, Gerald L.; Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael. Mandell's Principles and Practices of Infection Diseases 6th. Churchill Livingstone. 2004 [2020-04-20]. ISBN 0-443-06643-4. (原始内容存档于2018-07-30).

- ^ Christopher, PR; David, KV, John, SM, Sankarapandian, V. Antibiotic therapy for Shigelladysentery.. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2010-08-04, (8): CD006784. PMID 20687081. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006784.pub4.

- ^ Effa, EE; Lassi, ZS, Critchley, JA, Garner, P, Sinclair, D, Olliaro, PL, Bhutta, ZA. Fluoroquinolones for treating typhoid and paratyphoid fever (enteric fever).. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2011-10-05, (10): CD004530. PMID 21975746. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004530.pub4.

- ^ Gonzales, ML; Dans, LF, Martinez, EG. Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis.. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2009-04-15, (2): CD006085. PMID 19370624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub2.

- ^ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-140235-7. (原始内容存档于2012-08-04).

- ^ Feldman, Mark; Friedman, Lawrence S.; Sleisenger, Marvin H. Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease 7th. Saunders. 2002 [2016-11-04]. ISBN 0-7216-8973-6. (原始内容存档于2007-09-27).

- ^ Elliott, EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children.. BMJ (Clinical research ed. ). 2007-01-06, 334 (7583): 35–40. PMC 1764079 . PMID 17204802. doi:10.1136/bmj.39036.406169.80.

- ^ Black, RE; Cousens, S, Johnson, HL, Lawn, JE, Rudan, I, Bassani, DG, Jha, P, Campbell, H, Walker, CF, Cibulskis, R, Eisele, T, Liu, L, Mathers, C, Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and, UNICEF. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis.. Lancet. 2010-06-05, 375 (9730): 1969–87. PMID 20466419. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1.

- ^ Tate, JE; Burton, AH, Boschi-Pinto, C, Steele, AD, Duque, J, Parashar, UD, WHO-coordinated Global Rotavirus Surveillance, Network. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2012 Feb, 12 (2): 136–41. PMID 22030330. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5.

- ^ World Health Organization. Global networks for surveillance of rotavirus gastroenteritis, 2001–2008 (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. November 2008, 47 (83): 421–428 [2012-05-10]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-07-09).

- ^ Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, Monasch R. Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78 (10): 1246–55. PMC 2560623 . PMID 11100619.

- ^ Gastroenteritis. Oxford English Dictionary 2011. [2012-01-15]. (原始内容存档于2008-01-11).

- ^ antiquusmorbus. com/English/English. htm Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms 请检查

|url=值 (帮助). [2020-09-17]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-20). - ^ Flahault, A; Hanslik, T. [Epidemiology of viral gastroenteritis in France and Europe].. Bulletin de l'Academie nationale de medecine. 2010 Nov, 194 (8): 1415–24; discussion 1424–5. PMID 22046706.

- ^ Albert, edited by Neil S. Skolnik ; associate editor, Ross H. Essential infectious disease topics for primary care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. 2008: 66 [2016-11-04]. ISBN 978-1-58829-520-0. (原始内容存档于2013-10-16).

- ^ World Health Organization. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Diarrhoeal Diseases. [2012-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-14).

- ^ World Health Organization. Shigellosis. Diarrhoeal Diseases. [2012-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-14).

- ^ Weese, JS. Bacterial enteritis in dogs and cats: diagnosis, therapy, and zoonotic potential.. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. 2011 Mar, 41 (2): 287–309. PMID 21486637. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.12.005.

- ^ Rousseaux, Wanda Haschek, Matthew Wallig, Colin. Fundamentals of toxicologic pathology 2nd ed. London: Academic. 2009: 182 [2016-11-04]. ISBN 9780123704696. (原始内容存档于2013-12-26).

- ^ MacLachlan, edited by N. James; Dubovi, Edward J. Fenner's veterinary virology 4th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. 2009: 399 [2016-11-04]. ISBN 9780123751584. (原始内容存档于2013-12-16).

- ^ al. ], edited by James G. Fox . . . [et. Laboratory animal medicine 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Academic Press. 2002: 649 [2016-11-04]. ISBN 9780122639517. (原始内容存档于2013-12-16).

- ^ al. ], edited by Jeffrey J. Zimmerman . . . [et. Diseases of swine 10th ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. : 504 [2016-11-04]. ISBN 9780813822679. (原始内容存档于2013-12-26).

来源

编辑- Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael Dolin (编). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2010. ISBN 0-443-06839-9.