阿奇霉素

阿奇黴素(INN:azithromycin)另譯阿紅黴素 、阿齊紅黴素及亞茲索黴素,以 Zithromax(口服形式)和 Azasite(眼藥水形式)等商品名稱於市面銷售,是一種是屬於大环内酯的抗生素,用於治療若干種病菌感染,[9]包括中耳炎、鏈球菌性咽炎、肺炎、旅行者腹瀉和某些胃腸炎。[9]也用於治療某些性傳染病,包含衣原體感染疾病和淋病,或可與不同藥物聯合使用,以治療瘧疾。[9]給藥方式有口服給藥、靜脈注射或是用於眼睛的眼藥水。[9]

| |

| |

| 臨床資料 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Zithromax及其他[1] |

| 其他名稱 | 9-deoxy-9α-aza-9α-methyl-9α-homoerythromycin A |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697037 |

| 核准狀況 | |

| 懷孕分級 | |

| 给药途径 | 口服給藥、intravenous或眼藥水 |

| 藥物類別 | 巨環內酯抗生素 |

| ATC碼 | |

| 法律規範狀態 | |

| 法律規範 |

|

| 藥物動力學數據 | |

| 生物利用度 | 38%(250毫克膠囊劑量) |

| 药物代谢 | 肝臟 |

| 生物半衰期 | 68小時 |

| 排泄途徑 | 膽管[7] |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 83905-01-5 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.126.551 |

| 化学信息 | |

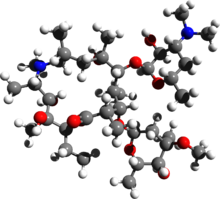

| 化学式 | C38H72N2O12 |

| 摩尔质量 | 749.00 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

使用此藥物常見的副作用有噁心、嘔吐、腹瀉和胃部不適。[9]可能會出現過敏反應,例如過敏性休克,或是艱難擬梭菌感染導致的腹瀉。[9]阿奇黴素會導致心電圖中QT間期延長,可能導致危及生命的心律不整(例如尖端扭轉型室性心搏過速)。[10]個體於懷孕期間使用未發現會對胎兒造成危害。[9]而在母乳哺育期間的個體使用,對於嬰兒的安全性尚未得到證實,但可能屬於安全。[11]阿奇黴素是一種阿扎利德類抗生素,是巨環內酯類抗生素家族中的一種。[9]它的作用是減少病菌蛋白質的產生,而阻止其生長。[9][12]

阿奇黴素於1980年由南斯拉夫(現為克羅埃西亞)名為Pliva製藥(目前已為梯瓦製藥子公司)發現,並於1988年取得用於醫療用途的核准。[13][14]它已列入世界衛生組織基本藥物標準清單之中,[15]歸類為巨環內酯類和酮內酯類抗生素。此外,世界衛生組織(WHO)也將其列為對抗日益嚴重的抗生素抗藥性不可或缺的藥物。 [16]市面上有其通用名藥物販售。[17]此藥物於市面上有為數眾多的品牌流通。[1]其於2022年在美國最常使用處方藥中排名第78,開立的處方箋數量超過800萬張。[9][18]

此藥物的通用名药物價格也十分親民,[19]一劑批發價約在0.18-2.98美元左右。[20]截止2018年,在美國的每個疗程花费约为4美元。[21]

醫療用途

编辑阿奇黴素用於治療多種感染,包括:急性細菌性鼻窦炎、咽炎、扁桃体炎等上呼吸道感染、[22]急性中耳炎、[23][24]沙眼、[25]包括支气管炎、社區型肺炎等下呼吸道感染[26]。

阿奇霉素另可用于男女性传播疾病中沙眼衣原体所导致的单纯性生殖器感染。亦可用于由非多重耐药淋球菌所致的单纯性生殖器感染及由杜克嗜血杆菌引起的软下疳(需排除霉素螺旋体的合并感染、單純性皮膚感染、恙蟲病,[27]以及預防和治療細菌性慢性阻塞性肺病急性惡化。[28]

抗菌效力

编辑阿奇黴素具有相對廣泛但較淺的抗菌活性。它可抑制一些革蘭氏陽性菌(需氧和兼性革蘭氏陽性微生物)、一些革蘭氏陰性菌(需氧和兼性厭氧革蘭氏陰性微生物)和許多非典型細菌(厭氧微生物及其他微生物)。[29][30][31]

懷孕和哺乳時期

编辑目前尚未發現個體於懷孕期間使用阿奇黴素會對胎兒有不良影響。[9]但也尚未對於此有充分的研究。[7]

雖然目前研究顯示母乳中阿奇黴素濃度較低,且該藥物也用於治療幼兒,但此藥物在哺乳期對嬰兒的安全性仍有待進一步確認。哺乳婦女若要使用此藥,建議諮詢醫師,以利評估風險與效益,並在醫師指導下用藥。。[11]

呼吸道疾病

编辑阿奇黴素之所以能有效改善氣喘症狀,在於其兼具抗菌、抗病毒和抗發炎等多重作用,能從不同面向抑制哮喘的發展。

阿奇黴素似可透過抑制發炎過程,有效治療慢性阻塞性肺病。[[32]阿奇黴素可能透過這種機制能有效治療鼻竇炎。[33]據信阿奇黴素透過抑制某些可能導致呼吸道發炎的免疫反應而產生效用。[34][35]

用法用量

编辑连用三日

- 成人:500毫克/次/日

- 儿童:250毫克/次/日

禁忌

编辑对巨环内酯类抗生素过敏者禁用。

注意

编辑动物实验显示本品对胎儿无影响,但在人类孕妇中应用尚缺乏经验,故在孕妇中应用须充分权衡利弊。尚无资料显示本品是否可分泌至母乳中,故哺乳期妇女应用须谨慎考虑。

不良反應

编辑使用此藥物最常見的不良反應有腹瀉 (5%)、噁心 (3%)、腹痛 (3%) 和嘔吐。不到1%的人因副作用而停止服用。有發生神經緊張、皮膚反應和過敏性休克的報導。[36]有發生艱難擬梭菌感染的報導。[9]另有转氨酶升高(少数患者出现胆汁淤积性肝炎)及少数患者出现白细胞计数减少。阿奇黴素不會影響避孕藥的功效,與某些抗生素(如利福平)不同。也有聽力損失的報導。[37]

美國食品藥物管理局(FDA)於2013年發出警告:阿奇黴素會導致心電圖中QT間期延長,可能導致危及生命的心律不整(例如尖端扭轉型室性心搏過速}),[10]对于已存在心脏问题(比如长Q-T间期综合症、低钾/镁血症、心率异常/过慢等)的患者的风险明显增高,更須謹慎。[38][39][40]

藥物交互作用

编辑与氢氧化铝、硫酸镁等抗酸药同时服用会降低阿齐霉素的血浆浓度峰值。与牛奶或其他乳制品同时服用,并不减弱药性。

秋水仙素

编辑阿奇黴素不應與秋水仙素一起服用,因為可能導致個體發生秋水仙素中毒。秋水仙素中毒的症狀有胃腸道不適、發燒、肌肉痛、全血細胞減少和器官衰竭。[41][42]

抑制CYP3A4作用

编辑阿奇黴素能輕微抑制CYP3A4(身體中的一種重要的酶,主要存在於肝臟和小腸。它可以氧化外源有機小分子(異生素,xenobiotics),如毒素或藥物,以便讓其排出體外)的活性,因此對他汀類藥物的藥物代謝動力學影響不大,被認為是種比其他巨環內酯類抗生素更安全的選擇。[43]

藥理學

编辑作用機轉

编辑阿奇黴素的作用機制是結合細菌核糖體的50S次單位(50S subunit),阻斷信使核糖核酸(mRNA)的轉譯過程,進而抑制蛋白質合成,最終導致細菌死亡。值得注意的是阿奇黴素不會影響細菌的核酸合成。[7]

藥物代謝動力學

编辑阿奇黴素是一種酸穩定的抗生素,因此可口服,不會被胃酸破壞。它很容易被吸收,但空腹服用會有更好的吸收效果。口服劑型的成人最大血藥濃度(Tmax)需時2.1至3.2小時。由於阿奇黴素的生物半衰期較長,因此一次給藥較大劑量後,藥物能長時間停留在體內,持續發揮抗菌作用。[7]

阿奇黴素的生物半衰期長達68小時,一次服用500毫克劑量後,藥物能長時間停留在體內。[7]多數以藥物原形排出人體(主要經由膽汁,[44]少量經由尿液[7])。

其他

编辑根據美Cassondra L Cramer et al. (2017) 之綜合性報告- 已被證實有如其他 Macrolide 類藥物之 bacteriostatic 非殺菌 bacteriocidal 作用,但它還有很強之免疫調節作用,已証明很有効用於各類慢性疾病,因它能降低在急性階段產生之促進炎症之細胞激素 pro-inflammatory cytokines 而促進緩解後階段炎症有利治療急性呼吸宭迫症而對抗 cytokinin storm。實際上它對呼吸道上皮細胞有直接作用,因而維護其作用而減少粘液分泌,因此它可用之於各類慢性肺部疾病包括慢性阻塞性肺病/Cystic fibrosis(CF)/非CF支氣管擴張症/彌漫性泛支氣管炎/小支氣管炎/bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 及氣喘等 ,還有急性細菌性鼻竇炎/急性細菌性中耳炎/咽喉炎/扁桃炎/慢性氣管炎急性惡化/民間所患肺炎;更防治菌類 Mycobacterium avium 最重要乃對會致命之敗血症有効[45]。

依反應出現次序 : *臨床効用:抗細菌/抗炎症/抗分泌/組織修復及治癒——肺上皮細胞恢復其作用。 *細胞性作用:減少PMN嗜中性白血球、大吞噬細胞及其他炎症細胞之轉移,增加PMN之自我死亡及 T helper cell 轉傾成 Th-2。 *生化作用:經由抑制 Transcription Factor nuclear factor-Kappa B NfK-B 降低 pro-inflammatory cytokinines 促進炎症之細胞激素包括 lL-8,IL-6,GM-CSF,MMPs,TNF-a 等更會降低ROS。

化学合成

编辑将红霉素肟(Erythromycin Oxime)经贝克曼重排(Beckmann Rearrangement)后得到扩环产物,再经还原、N-甲基化等反应,将氮原子引入到大环内酯骨架中,制得含氮的15元环红霉素衍生物阿奇霉素。

歷史

编辑藥物由Pliva製藥於1980年發現。[46]Pliva製藥與1981年為其取得專利。[14]繼而與輝瑞製藥簽約,讓輝瑞製藥擁有在西歐和美國獨家銷售的權利。Pliva製藥自行在中歐與東歐進行銷售。輝瑞製藥另外於1991年取得授權,在前述以外市場以Zithromax的商品名稱銷售此藥物。[47]阿奇黴素的專利保護於2005年到期。[48]

社會與文化

编辑市售配方

编辑市面上有阿奇黴素的通用名藥物流通。此藥物有薄膜錠、膠囊、口服懸浮液、靜脈注射液、袋裝顆粒懸浮液和眼藥水等劑型。[1]

使用

编辑於2010年,阿奇黴素是美國門診最常開立的抗生素,[49]而在瑞典,門診抗生素的使用率只有美國的3分之1,巨環內酯類抗生素僅佔使用處方藥中的3%。[50]於2017年和2022年,阿奇黴素是美國門診第二常用的抗生素。[51][52]而此藥物於2022年是美國第78位最常使用的處方藥,開立處方籤數量有800萬份。[53][54]

品牌名稱

编辑阿奇黴素在全球以甚為眾多的商品名稱銷售。[1]如:日舒、维宏、派奇、泰利特、希舒美。

研究

编辑阿奇黴素被認為能透過抑制促發炎細胞因子的產生,同時增強抗發炎細胞因子的生成,來達到減輕炎症的作用。

阿奇黴素不僅用於治療感染,其在治療各種疾病,包括呼吸系統疾病(如囊腫性纖維化惡化、氣喘和慢性阻塞性肺病)以及由SARS-CoV-2引起的COVID-19等,都受到廣泛的研究。[55][56][57][58][59]在針對治療COVID-19方面的研究,後來以成效不佳,或是有副作用,而不再進行。[60][61][62][63]

药物分类

编辑- 红霉素衍生物

- 大环内酯类抗生素

參見

编辑參考文獻

编辑- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Azithromycin International Brands. Drugs.com. [2017-02-27]. (原始内容存档于2017-02-28).

- ^ Azithromycin Use During Pregnancy. Drugs.com. 2 May 2019 [2019-12-24]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-18).

- ^ Zithromax azithromycin 500mg (as dihydrate) tablet blister pack (58797). Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 2022-08-12 [2024-04-26].

- ^ Zithromax Product information. Health Canada. 2013-01-16 [2024-04-26].

- ^ Drug and medical device highlights 2018: Helping you maintain and improve your health. Health Canada. 2020-10-14 [2024-04-17].

- ^ Zithromax Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). (emc). 2024-02-05 [2024-04-26].

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Zithromax- azithromycin dihydrate tablet, film coated; Zithromax- azithromycin dihydrate powder, for suspension. DailyMed. 2023-09-29 [2024-04-26].

- ^ List of nationally authorised medicinal products Active substance: azithromycin (systemic use formulations) (PDF). European Medicine Agency. 2021-01-14 [2023-03-10]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-08-18).

- ^ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 Azithromycin. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [2015-08-01]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-05).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Dunker A, Kolanczyk DM, Maendel CM, Patel AR, Pettit NN. Impact of the FDA Warning for Azithromycin and Risk for QT Prolongation on Utilization at an Academic Medical Center. Hosp Pharm. November 2016, 51 (10): 830–833. PMC 5135431 . PMID 27928188. doi:10.1310/hpj5110-830.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Azithromycin use while Breastfeeding. [2015-09-01]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-05).

- ^ Azithromycin Stops The Growth of Bacteria. [2017-12-24]. (原始内容存档于2020-05-12) (德语).

- ^ Greenwood D. Antimicrobial drugs : chronicle of a twentieth century medical triumph 1st. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008: 239. ISBN 978-0-19-953484-5. (原始内容存档于2016-03-05).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Alapi EM, Fischer J. Table of Selected Analogue Classes. Fischer J, Ganellin CR (编). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. Weinheim: Wiley-Vch Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. 2006: 498 [2020-04-02]. ISBN 978-3-527-31257-3. (原始内容存档于2023-01-14).

- ^ World Health Organization. The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. hdl:10665/371090 . WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ World Health Organization. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine 6th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018. ISBN 978-92-4-151552-8. hdl:10665/312266 . License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Hamilton R. Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2015. ISBN 978-1-284-05756-0.

- ^ Azithromycin Stops The Growth of Bacteria. [2017-12-24]. (原始内容存档于2020-05-12) (德语).

- ^ Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia 2015 deluxe lab coat edition.. Jones & Bartlett Learning https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922644939. 2014-01-01 [2016-12-16]. OCLC 922644939. (原始内容存档于2019-07-13). 缺少或

|title=为空 (帮助) - ^ Azithromycin. International Drug Price Indicator Guide. [4 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2020-03-24).

- ^ National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) Retrieved 24 May 2018.. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (原始内容存档于2018-05-24).

- ^ Klapan I, Culig J, Oresković K, Matrapazovski M, Radosević S. Azithromycin versus amoxicillin/clavulanate in the treatment of acute sinusitis. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 1999, 20 (1): 7–11 [2024-05-31]. PMID 9950107. doi:10.1016/S0196-0709(99)90044-3.

In adults with acute sinusitis, a 3-day course of azithromycin was as effective and well tolerated as a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. A significantly simpler dosage regimen and faster clinical effect were the advantages of azithromycin.

- ^ Dawit G, Mequanent S, Makonnen E. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin and amoxicillin/clavulanate for otitis media in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2021, 20 (1): 28. PMC 8070272 . PMID 33894769. doi:10.1186/s12941-021-00434-x .

Azithromycin is comparable to amoxicillin/clavulanate to treat otitis media in children, and it is safer and more tolerable.

- ^ Randel A. IDSA Updates Guideline for Managing Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis. American Family Physician. September 2013, 88 (5): 338–40. PMID 24010402.

- ^ Burton M, Habtamu E, Ho D, Gower EW. Interventions for trachoma trichiasis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. November 2015, 11 (11): CD004008. PMC 4661324 . PMID 26568232. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004008.pub3.

- ^ Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7107997

|PMC=缺少标题 (帮助). March 2007, 44 (Suppl 2): S27–72. PMC 7107997 . PMID 17278083. doi:10.1086/511159 . - ^ Burton M, Habtamu E, Ho D, Gower EW. Interventions for trachoma trichiasis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. November 2015, 11 (11): CD004008. PMC 4661324 . PMID 26568232. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004008.pub3.

- ^ Taylor SP, Sellers E, Taylor BT. Azithromycin for the Prevention of COPD Exacerbations: The Good, Bad, and Ugly. The American Journal of Medicine. December 2015, 128 (12): 1362.e1–6. PMID 26291905. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.07.032 .

- ^ Sybilski AJ. Azithromycin – more than an antibiotic. Pediatria I Medycyna Rodzinna. 2020, 16 (3): 261–267. doi:10.15557/PiMR.2020.0048 .

- ^ Opitz DL, Harthan JS. Review of Azithromycin Ophthalmic 1% Solution (AzaSite) for the Treatment of Ocular Infections. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2012, 4: 1–14. PMC 3619494 . PMID 23650453. doi:10.4137/OED.S7791.

- ^ Amano A, Kishi N, Koyama H, Matsuzaki K, Matsumoto S, Uchino K, Yamaguchi H, Yokomizo A, Mizuno M. In vitro activity of sitafloxacin against atypical bacteria (2009-2014) and comparison between susceptibility of clinical isolates in 2009 and 2012. Jpn J Antibiot. September 2016, 69 (3): 131–142. PMID 30226949.

- ^ Simoens S, Laekeman G, Decramer M. Preventing COPD exacerbations with macrolides: a review and budget impact analysis. Respiratory Medicine. May 2013, 107 (5): 637–48. PMID 23352223. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.019 .

- ^ Gotfried MH. Macrolides for the treatment of chronic sinusitis, asthma, and COPD . Chest. February 2004, 125 (2 Suppl): 52S–60S; quiz 60S–61S [2020-03-22]. PMID 14872001. doi:10.1378/chest.125.2_suppl.52S. (原始内容存档于2021-08-27).

- ^ Zarogoulidis P, Papanas N, Kioumis I, Chatzaki E, Maltezos E, Zarogoulidis K. Macrolides: from in vitro anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties to clinical practice in respiratory diseases. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. May 2012, 68 (5): 479–503. PMID 22105373. S2CID 1904304. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1161-x .

- ^ Steel HC, Theron AJ, Cockeran R, Anderson R, Feldman C. Pathogen- and host-directed anti-inflammatory activities of macrolide antibiotics. Mediators of Inflammation //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3388425

|PMC=缺少标题 (帮助). 2012, 2012: 584262. PMC 3388425 . PMID 22778497. doi:10.1155/2012/584262 . - ^ Mori F, Pecorari L, Pantano S, Rossi ME, Pucci N, De Martino M, Novembre E. Azithromycin anaphylaxis in children. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2014, 27 (1): 121–6. PMID 24674687. S2CID 45729751. doi:10.1177/039463201402700116 .

- ^ Dart RC. Medical Toxology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004: 23.

- ^ Grady D. Popular Antibiotic May Raise Risk of Sudden Death. The New York Times. 2012-05-16 [2012-05-18]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-17).

- ^ Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. The New England Journal of Medicine. May 2012, 366 (20): 1881–90. PMC 3374857 . PMID 22591294. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003833.

- ^ FDA Drug Safety Communication: Azithromycin (Zithromax or Zmax) and the risk of potentially fatal heart rhythms. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2013-03-12. (原始内容存档于2016-10-27).

- ^ John R. Horn; Philip D. Hansten. Life Threatening Colchicine Drug Interactions. Drug Interactions: Insights and Observations (PDF). 2006 [2024-01-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-11-23).

- ^ Tan MS, Gomez-Lumbreras A, Villa-Zapata L, Malone DC. Colchicine and macrolides: a cohort study of the risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant exposure. Rheumatol Int. December 2022, 42 (12): 2253–2259. PMC 9473467 . PMID 36104598. doi:10.1007/s00296-022-05201-5.

- ^ Hougaard Christensen MM, Bruun Haastrup M, Øhlenschlaeger T, Esbech P, Arnspang Pedersen S, Bach Dunvald AC, Bjerregaard Stage T, Pilsgaard Henriksen D, Thestrup Pedersen AJ. Interaction potential between clarithromycin and individual statins-A systematic review (PDF). Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. April 2020, 126 (4): 307–317 [2024-02-02]. PMID 31628882. doi:10.1111/bcpt.13343. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2024-02-02).

- ^ Bekele LK, Gebeyehu GG. Application of Different Analytical Techniques and Microbiological Assays for the Analysis of Macrolide Antibiotics from Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms and Biological Matrices. ISRN Analytical Chemistry. 2012, 2012: 1–17. doi:10.5402/2012/859473 .

- ^ Immunomodulatory indications of azithromycin in respiratory disease: a concise review for the clinician. Postgrad Med. 2017-06, 129 (5): 493–499 [2024-10-04]. doi:10.1080/00325481.2017.1285677. (原始内容存档于2024-10-07) (英语).

- ^ Banić Tomišić Z. The Story of Azithromycin. Kemija U Industriji: Časopis Kemičara I Kemijskih Inženjera Hrvatske. December 2011, 60 (12): 603–17 [2020-06-25]. (原始内容存档于2024-03-08).

- ^ Banić Tomišić Z. The Story of Azithromycin. Kemija U Industriji. 2011, 60 (12): 603–617 [2013-04-15]. ISSN 0022-9830. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ Azithromycin: A world best-selling Antibiotic. www.wipo.int. World Intellectual Property Organization. [2019-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-06).

- ^ Hicks LA, Taylor TH, Hunkler RJ. U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010. The New England Journal of Medicine. April 2013, 368 (15): 1461–2. PMID 23574140. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1212055 .

- ^ Hicks LA, Taylor TH, Hunkler RJ. More on U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010. The New England Journal of Medicine. September 2013, 369 (12): 1175–6. PMID 24047077. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1306863.

- ^ Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions — United States, 2017 (PDF). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020-03-26 [2020-03-30]. (原始内容存档于2020-03-30).

- ^ Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions — United States, 2022. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2023-11-15 [2023-11-17]. (原始内容存档于2024-03-08).

- ^ The Top 300 of 2022. ClinCalc. [2024-08-30]. (原始内容存档于2024-08-30).

- ^ Azithromycin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022. ClinCalc. [2024-08-30].

- ^ Durán-Álvarez JC, Prado B, Zanella R, Rodríguez M, Díaz S. Wastewater surveillance of pharmaceuticals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico City and the Mezquital Valley: A comprehensive environmental risk assessment. Sci Total Environ. November 2023, 900: 165886. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.90065886D. PMID 37524191. S2CID 260323001. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165886.

- ^ Southern KW, Barker PM. Azithromycin for cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. November 2004, 24 (5): 834–8. PMID 15516680. S2CID 17778741. doi:10.1183/09031936.04.00084304 .

- ^ Azithromycin and cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. August 2022, 107 (8): 739. PMID 35853636. S2CID 250624603. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2022-324569.

- ^ Ghimire JJ, Jat KR, Sankar J, Lodha R, Iyer VK, Gautam H, Sood S, Kabra SK. Azithromycin for Poorly Controlled Asthma in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. June 2022, 161 (6): 1456–1464. PMID 35202621. S2CID 247074537. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.02.025.

- ^ Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, Reynolds PN, Hodge S, James AL, Jenkins C, Peters MJ, Marks GB, Baraket M, Powell H, Taylor SL, Leong LEX, Rogers GB, Simpson JL. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. August 2017, 390 (10095): 659–668. PMID 28687413. S2CID 4523731. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31281-3.

- ^ Popp M, Stegemann M, Riemer M, Metzendorf M, Romero CS, Mikolajewska A, Kranke P, Meybohm P, Skoetz N, Weibel S. Intervention Antibiotics for the treatment of COVID-19. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 22 October 2021, 10 (10): CD015025. PMC 8536098 . PMID 34679203. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015025.

- ^ Nag K, Tripura K, Datta A, Karmakar N, Singh M, Singh M, Singal K, Pradhan P. Effect of Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin Combination Use in COVID-19 Patients - An Umbrella Review. Indian J Community Med //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10900474

|PMC=缺少标题 (帮助). 2024, 49 (1): 22–27. PMC 10900474 . PMID 38425958. doi:10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_983_22 . - ^ Butler CC, Yu LM, Dorward J, Gbinigie O, Hayward G, Saville BR, Van Hecke O, Berry N, Detry MA, Saunders C, Fitzgerald M, Harris V, Djukanovic R, Gadola S, Kirkpatrick J, de Lusignan S, Ogburn E, Evans PH, Thomas NP, Patel MG, Hobbs FD. Doxycycline for community treatment of suspected COVID-19 in people at high risk of adverse outcomes in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. September 2021, 9 (9): 1010–1020. PMC 8315758 . PMID 34329624. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00310-6.

- ^ Platform trial rules out treatments for COVID-19 . National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). 31 May 2022 [1 June 2022]. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_50873. (原始内容存档于1 June 2022).

- 茲林卡·坦布拉舍芙, 一位在抗生素開發領域發揮重要貢獻的女性科學家。她發現阿奇黴素,對全球的醫療保健產生深遠影響。