疟疾

疟疾(拉丁语:Malaria,中文俗称打摆子[5]、冷热病[6]、发疟子[7]),是一种会感染人类及其他动物的全球性寄生虫传染病,其病原疟原虫借由蚊子散播[2],隶属囊泡藻界(统称原生生物的生物类群之一),皆为单细胞生物。疟疾引起的典型症状有发热、畏寒、疲倦、呕吐和头痛[8];在严重的病例中会引起黄疸、癫痫发作、昏迷或死亡[1]。这些症状通常在蚊子叮咬后的十到十五天内出现,若病人没有接受治疗,症状缓解后数月内症状可能再次出现[2]。曾感染疟疾的患者再次感染所引起的症状通常较轻微,如果患者没有持续暴露于疟疾的环境,此种部分抵抗力会在数月至数年内消失[1]。

| 疟疾 | |

|---|---|

| |

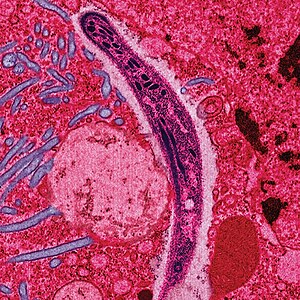

| 疟原虫从雌蚊唾液移入蚊子细胞。 | |

| 症状 | 发热、呕吐、头痛[1] |

| 并发症 | 黄疸、癫痫发作、昏迷[1] |

| 起病年龄 | 暴露后10–15日[2] |

| 类型 | 原虫传染、媒介传播疾病[*]、疾病 |

| 病因 | 病媒蚊散布疟原虫[1] |

| 诊断方法 | 血液抹片、抗原检测[1] |

| 预防 | 蚊帐、防蚊液、病媒蚊控制、药物[1] |

| 药物 | 抗疟药[2] |

| 患病率 | 全球约2.96亿人(2015年)[3] |

| 死亡数 | 约730,500人(2015年)[4] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 感染科 |

| ICD-9-CM | 084、084.6 |

| OMIM | 248310 |

| DiseasesDB | 7728 |

| MedlinePlus | 000621 |

| eMedicine | 221134、784065 |

| Orphanet | 673 |

疟疾最常透过受感染的雌性疟蚊来传播,疟原虫会在疟蚊叮咬时从蚊子的唾液传入人类的血液[2],接着疟原虫会随血液移动至肝脏,在肝细胞中发育成熟和繁殖。疟原虫属(Plasmodium)中有五个种可以感染人类并借此散播[1],多数死亡案例由恶性疟(P. falciparum)、间日疟(P. vivax)及卵形疟(P. ovale)所造成,三日疟(P. malariae)产生的症状较轻微[1][2],而猴疟虫(P. knowlesi,又称诺氏疟原虫)则较少造成人类疾病[2]。疟疾的诊断方式主要为血液抹片镜检或前者配合快速疟疾抗原诊断测试[1],近年也发展聚合酶链式反应来侦测疟原虫的DNA,但因为成本和复杂性较高,目前尚未广泛地应用于疟疾的盛行地区[9]。

避免疟蚊叮咬能降低感染疟疾的风险,实务上包括使用蚊帐、防蚊液或控制蚊虫生长(如喷洒杀虫剂和清除积水)[1]。前往疟疾盛行地区的旅客可以使用数种药物来预防疟疾,而疟疾好发地区的婴儿及第一个三月期以后的孕妇也建议适时使用周效磺胺/比利美胺进行防治[10][11]。20世纪中叶,中国科学家团队研制出抗疟药物青蒿素,团队成员之一的屠呦呦因此获得2015年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[12]。2021年10月,第一个由WHO认可的疟疾疫苗RTS,S,可以对有风险的儿童广泛使用[13],同时其他疫苗的研究仍在进行[2]。现在建议的治疗方法是并用青蒿素及另一种抗疟药物[1][2](可能是甲氟喹、苯芴醇或周效磺胺/比利美胺[14]);如果青蒿素无法取得,则可使用奎宁加上去氧羟四环素[14]。为避免疟原虫抗药性增加,疟疾盛行地区的病患应尽量在确诊后才开始投药。疟原虫已逐渐对几种药物产生抗药性[15],具有氯喹(氯喹)抗性的恶性疟已经散布到多数的疟疾盛行区,青蒿素抗药性的问题在部分东南亚地区也日益严重[2]。

主要流行地区包括非洲中部、南亚、东南亚及拉丁美洲,这其中又以非洲的疫情最甚[16][17][18]。根据世界卫生组织的统计,2013年全球疟疾病例共有1.98亿例[19],造成584,000至855,000人死亡,当中有90%是在非洲发生[2][20]。

疟疾普遍存在热带及亚热带地区位于赤道周围的广大带状区域[1],包含漠南非洲、亚洲,以及拉丁美洲等等。2015年,全球约有2.14亿人新感染疟疾,并造成多达43.8万人死亡,其中有90%的死亡病例位于非洲[21]。2000年至2015年间,病例数减少37%[21],但自2014年的1.98亿例之后开始回升[22]。疟疾与贫困息息相关,并严重影响经济发展[17][18]。疟疾会造成医疗卫生支出增加、劳动力减少、并冲击观光业,非洲每年估计因疟疾损失120亿美元[23]。

历史

编辑恶性疟原虫已存在约5至10万年,但直到1万年前族群数量才开始增加,这可能与人类发展农业并群聚定居有关[24]。人类疟原虫的近亲物种迄今仍时常感染黑猩猩,一些证据显示恶性疟原虫可能源于感染大猩猩的物种[25]。公元前2700年起,中国就有关于疟疾引起的独特的周期性发烧的历史记载[26]。希波克拉底按发热周期把疟疾分为间日疟、三日疟、次间日疟和每日疟[27]:3[28]。罗马人科鲁迈拉也曾经提到疟疾可能与沼泽有关[27]:3。疟疾在罗马非常流行,以致它有“罗马热”之称[29],并可能和罗马帝国的衰落有关[30]。当时罗马帝国内的南意大利、萨丁尼亚岛、彭甸沼地、伊特鲁里亚沿岸及罗马城的台伯河沿岸由于气候条件适宜病媒蚊生长,推测可能是当时的疫区。这些地区的灌溉花园、沼泽地、田地径流,和道路积水为蚊子提供了繁殖的理想场所[31]。

疟疾在中国历史上很早就有所纪载。《尚书·金滕》中就有提到就曾记载周武王“遘厉虐疾”[注 1],然而此处的“虐疾”是否真正指现代意义的疟疾已无从稽考[32]。“疟”在中国作为一个专属病症名可以追溯到《左传》[注 2]。《说文》中释“疟”为“热寒休作,从广从虐,虐亦声”[32]。

疟疾的英文“malaria”最早于1829年见诸文献[27],此字源自于中世纪意大利文的“mala aria”,意为“瘴气”。在这之前有文献称疟疾为“ague”,或是“沼泽热”(marsh fever),此乃因疟疾常发生于沼泽地区[33]。疟疾曾经是欧洲和北美最常见的疾病[34],虽然现在已经不再流行[35],但境外移入病例仍时有所闻[36]。

1880年,疟疾在科学研究上取得重大进展。法国军医夏尔·路易·阿方斯·拉韦朗在阿尔及利亚君士坦丁首次发现疟疾感染者的红血球里有寄生虫,于是他提出这种寄生虫是导致疟疾的生物,这是人类发现的第一种致病的原生生物,这项发现也使他获得1907年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[37]。一年后,古巴医生卡洛斯·芬莱在哈瓦那为人治疗黄热病时,发现了蚊子在人际间传播疾病的有力证据[38],他的研究乃奠基于约西亚·克拉克·诺特[39]和“热带医学之父”万巴德爵士在丝虫病传播上的研究[40]。

1894年4月,苏格兰内科医师罗纳德·罗斯拜访万巴德在伦敦安妮皇后街的住处,此后四年两人潜心投入疟疾研究。1898年,时任职于加尔各答总统府总医院的罗斯证实蚊子是传播鸟疟疾的病媒,并提出疟原虫的完整生活史。他先让蚊子叮咬感染疟疾的鸟类,之后再取出蚊子的唾腺,并成功分离出疟原虫,进而推论蚊子是传播人类疟疾的病媒[41]。罗斯从印度医疗体系退休后,进入刚成立的利物浦热带医学院任职,并在埃及、巴拿马、希腊,和毛里求斯等地展开防疫工作[42]。1900年,沃尔特·里德(Walter Reed)领导的医疗委员会证实了芬莱和罗斯的发现,罗斯因此获得1902年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[41]。威廉·戈加斯在兴建巴拿马运河的工程中采用了沃尔特对于卫生措施的建议,这些建议挽救了上千工人的生命,并为之后的防疫工作提供借鉴[43]。

第一种对疟疾有效的治疗方式是使用金鸡纳树的树皮,金鸡纳树生长于秘鲁安第斯山脉的山坡上。秘鲁原住民将树皮入酒来治疗发烧,后来发现它也能用来治疗疟疾。该疗法在1640年左右由耶稣会传入欧洲,并于1677年收录至伦敦药典中[44]。直到1820年,树皮中的有效成分奎宁才由法国化学家佩尔蒂埃和卡旺图分离出来[45][46]。

截至1920年代以前,奎宁都是主要的抗疟药,随后其他药物才陆续开发出来。1940年代,氯喹取代奎宁用于治疗疟疾;但1950年代,东南亚和南美首先出现了抗药性疟疾;1980年代时抗药性病株更已传播至全球[47]。1970年代,中国科学家团队从黄花蒿中成功提取青蒿素。青蒿素和其他抗疟药联用的“青蒿素联合疗法”成为治疗恶性和重症疟疾的推荐疗法[48]。屠呦呦因此获得2015年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[49]。

1917年到1940年代,间日疟原虫曾用于疟疾疗法(malariotherapy),即注射疟原虫进入人体以引起高烧来治疗疾病(如三期梅毒等)。发明者朱利叶斯·瓦格纳-尧雷格因此获得诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。不过这个方法很危险,会导致15%的患者死亡,所以已经停止使用[50]。

在DDT发明之前,巴西和埃及等热带地区就曾向积水中喷洒剧毒的含砷化合物巴黎绿来破坏孑孓(蚊子幼虫)的栖息繁殖环境,成功控制了疟疾疫情[51]。第一种用于室内喷洒的杀虫剂是DDT[52]。尽管DDT原先只是用来控制疟疾,后来农业也开始大量喷洒以防治害虫。DDT的滥用导致很多地区出现耐药的蚊子,斯氏疟蚊对DDT的抗药性和细菌的抗生素抗药性类似。1960年代,公众开始意识到DDT滥用的危害,最后很多国家在1970年代禁止在农业中使用DDT[53]。

目前有效的疟疾疫苗是RTS,S。1967年,科学家曾将受过辐射减毒后的疟原虫子孢子注入小鼠体内,成功引起了免疫反应,为疟疾疫苗的研制带来第一缕曙光。1970年代起,许多科学家投入大量精力于开发人类疟疾疫苗[54]。

主要病征

编辑疟疾会在疟原虫感染后8-25天出现症状[55],预防性服药可能延迟发病[9]。病人早期的症状和流行性感冒类似[56],最典型的症状为发热、畏寒、接着冒冷汗,其他可能的症状包括头痛、颤栗、关节痛、呕吐、溶血反应、疟原性贫血、黄疸、血尿、视网膜损害、抽搐等[57]。由于疟原虫的生理活动有明显的日夜周期,病患会阵发性地颤栗、发热、冒冷汗。间日疟和卵形疟的活动周期为2天(病患每2天会发热一次);三日疟为3天;恶性疟一般为36至48小时,但也可能持续发热而无明显周期。[58]

重症疟疾通常是由恶性疟原虫造成,通常在感染后9至30天发病[56]。脑疟疾的患者常产生神经系统疾病,包括姿态异常、眼球震颤、共轭凝视麻痹(眼球无法朝同一方向转动)、角弓反张、抽搐、昏迷[56]。

并发症

编辑疟疾常会导致一些严重的并发症。呼吸困难是恶性疟患者常见的并发症,多达25%的成人和40%的幼童会有此症状,成因可能是代谢性酸中毒造成的呼吸代偿、非心源性肺水肿、并发性肺炎和贫血;急性呼吸窘迫综合征在患有恶性疟的儿童中很少见,但却出现于5–25%的成人和多达29%的孕妇[59]。肾衰竭是黑水热的重要特征,疟原虫造成溶血后血红素进入尿液,而使尿液呈暗红色至黑色[56]。同时感染艾滋病的疟疾患者死亡风险会提高[60]。

恶性疟可能会影响脑部而导致脑疟疾,视网膜白化为此病临床上重要的判断依据[61],其他症状包括脾脏肿大、肝肿大、严重头痛、低血糖,以及肾衰竭造成的血红蛋白尿[56]。其并发症包括自发性出血、凝血功能障碍和休克[62]。孕妇得到疟疾可能会造成死胎、流产和胎儿体重过轻[63],这些症状特别常见于恶性疟患者,但也发生于部分间日疟病例[64]。

病因

编辑疟疾的致病原是疟原虫,一种胞内寄生的单细胞生物,属于顶复门疟原虫属。它们以疟蚊作为中间宿主,透过雌蚊叮咬来传播病原体[65]。疟原虫可以感染大部分的脊椎动物,这使得得生物学家可以通过建立生物模型(例如用老鼠做疟疾病理研究)来研究疟疾[65]。

种类

编辑疟原虫属中目前确认能感染人类的有五种[66][67]:恶性疟原虫(Plasmodium falciparum)、间日疟原虫(P. vivax)、三日疟原虫(P. malariae)、卵形疟原虫(P. ovale)、诺氏疟原虫(P. knowlesi)。恶性疟是最常见的感染性疟原虫(75%),亦是造成患者死亡率最高的种类[9];间日疟是第二常见的疟原虫(20%),也是非洲以外地区最常见的种类[68];传统上认为恶性疟造成多数的死亡病例[69],但近期研究显示间日疟对患者造成的生命威胁可能和恶性疟差不多[70]。虽然曾有文献指出一些猿类可能会传染疟疾给人类,但除了诺氏疟原虫之外,其余都没有公共卫生上的重要性[71]。

当蚊子一旦受疟原虫感染,一向贪吃的它们会变得胃口大减。科学家指出,由于疟原虫必须在蚊子肠道内繁殖,才能将后代传播给人类。假使蚊子在体内疟原虫繁殖期间四处吸血,被打死的风险会大增,对疟疾虫毫无好处。等到十天过后,疟原虫的幼虫处在发育过程中传染力较强的阶段,它们会侵入蚊子的唾腺,透过阻断抗凝血物质的分泌,使蚊子每次试图吸血时,尖喙很快会被血小板堵住,缩短吸食血液的时间来刺激蚊子食欲,让受挫的蚊子吸不到足够的血液量,刺激它叮咬更多宿主以填饱肚子。而且当疟原虫入侵宿主的循环系统,还会干扰制造血小板的能力,让蚊子叮咬时,血液流动得更快。使这种有如飞行针筒的昆虫得以吸取更多受疟原虫感染的血液,并传染给下一个人[72]。

中国以间日疟最为常见,恶性疟其次,三日疟和卵形疟则较罕见。恶性疟主要发生在西南与海南,间日疟常发生在东北、华北、西北[73] 。全球暖化增加了疟蚊的活动范围,但对于疟疾传播的影响至今仍不明确[74][75]。

生活史

编辑疟原虫的生命周期很复杂,雌疟蚊是疟原虫的最终宿主兼传播媒介。雌疟蚊唾液中长梭形的子孢子会叮咬的过程进入人体,并随血液运移到肝脏,于肝细胞内行无性生殖。子孢子在肝细胞内发育成熟后会分裂成数以千计的裂殖子,破坏肝细胞进入血液中,这个过程称为组织裂体生殖。裂殖子接着侵入红血球,依序发育为环状体(即早期滋养体)、滋养体、裂殖体,裂殖体成熟后会释放出8到24个裂殖子,这个过程称为血液裂体生殖。[76]:70-71

大部分的裂殖体会反复感染红血球并产生更多的裂殖体,只有少部分在侵入红血球后会发育为配子母细胞,同个红血球内的裂殖子会遵循相同的发育模式,且当环境恶劣时发育为配子母细胞的几率较大。在疟蚊叮咬人体时,疟原虫随血液进到疟蚊的肠道,环境温度降低和pH值改变促使配子母细胞发育为配子,进入有性生殖世代。雌、雄配子在中肠成熟后结合为合子,合子接着变长成为具活动力的卵动子,卵动子再穿出肠壁,在肠壁下形成卵囊。疟原虫在卵囊中行无性生殖,形成具单套染色体的子孢子,卵囊在成熟后破裂,子孢子进入蚊子的血体腔,穿透各种组织后进入蚊子的唾腺,准备感染新的脊椎动物宿主。[76]:70-71[77][78]

除了蚊虫感染外,疟原虫也可能经由输血感染,但此情况相当罕见[79]。1995年,台北荣民总医院发生了一起严重的院内感染案例,因输血方式不当造成4名病患感染恶性疟死亡[80]。

疟疾复发

编辑疟疾的患者可能会在一段无症状期后复发,此种复发现象可依成因不同而分为再燃(recrudescence)、复发(relapse)、重复感染(reinfection)三种。再燃是导因于血液中残存的疟原虫,无症状期的病人体内虽仍有疟原虫,但没有任何症状显现,这可能是治疗不完全或疗效不佳所致[14]:6。复发是指患者血液中的疟原虫虽已悉数清除,但肝细胞中仍有疟原虫的休眠体(hypnozoites)存在;此类的病人无症状期约有8至24周,这种现象在间日疟和卵形疟患者中常常发生[9],尤其温带地区的间日疟会以休眠体“越冬”,也就是在患者感染后的隔年年初才复发[81]。重复感染是指患者在成功清除旧病原体后又感染了新病原体,重复感染在临床上很难与复发区分,虽然两周内再次出现的疟疾通常是治疗失败造成的[14]:17。时常感染疟疾的患者可能会产生一定的免疫力[82]。

病理生理学

编辑致病机制

编辑疟疾的感染分为两个阶段:包括疟原虫在肝细胞内发育的红血球外期(exoerythrocytic phase)和疟原虫在红血球内发育的红血球内期(erythrocytic phase)。当受感染的疟蚊叮咬人类时,疟原虫的子孢子会随蚊子的唾液进入血流并移动至肝脏,在肝细胞内以无性繁殖大量增生,此时的病原体因受肝细胞的保护而难以透过免疫系统侦测[83],这段没有症状的时期持续约8至30天[84]。

经过一段潜伏期之后,疟原虫会产生数以千计的裂殖子,他们会打破肝细胞进入血液,侵入红血球,开始红血球内期。裂殖子在红血球内无性繁殖,并周期性地由红血球破出,接着再侵犯更多红血球。病患会周期性的发热就是裂殖子反复地释出和感染红血球造成的[84]。有些间日疟的子孢子在肝细胞内并不会快速发展为裂殖子,他们会先形成休眠体,潜伏7到10个月后才再度活化形成裂殖子(潜伏期也有可能长达数年)。间日疟这种特殊的生活史造成了前述的“复发”现象[81],而卵形疟是否也有这样的生活史目前仍不清楚[85]。

疟原虫大部分的时间都栖居在肝细胞和红血球中,因此可以轻易地躲避免疫系统侦测。但感染过的红血球结构上相当脆弱,容易在脾脏被摧毁,为了避免此一宿命,恶性疟会在红血球表面产生黏连蛋白,使血球能黏附在小血管的管壁上而不会随血液循环通过脾脏[86]。也因为这个机制,疟疾可能会造成微血管堵塞,产生胎盘疟疾等相关症状[87]。感染的红血球也可能破坏血脑屏障,使脑部微血管出血,造成脑疟疾[88]。

遗传抵抗力

编辑恶性疟原虫带来的高死亡率和罹病率,造成人类近代史上最大的演化压力,造成某些对疟疾有抵抗力的基因筛选出来。不幸地,这些基因通常也会造成红血球发育不良,导致镰刀型红血球疾病、海洋性贫血、蚕豆症、或红血球表面达菲抗原缺乏[89][90]。

镰刀型红血球造成的缺陷和其对疟疾的免疫力展现了生命在演化上为生存所做的权衡。带有镰刀型红血球基因的人,血红蛋白突变成为血红蛋白S,红血球因脱水而呈镰刀状(正常的红血球为双凹圆盘状),这种红血球因表面积减少,氧气输送的效率较低;且因细胞形状缺乏弹性,无法顺畅地在血液中循环,寿命也较短,所以寄居其内的疟原虫往往没有足够的时间发育成熟。由于输氧效率的降低,同型合子(来自父母的两套染色体都具有镰刀型红血球基因)的个体会罹患镰刀型细胞贫血症,而异形合子的个体则能在没有严重贫血的情形下保有对疟疾的抵抗力。虽然同型合子个体较短的寿命不利于演化,但由于它对疟疾的抵抗力,该性状在疟疾盛行区仍然保留了下来[90][91]

肝功能受损

编辑疟疾造成肝功能受损的情形并不多见,通常发生于同时罹患病毒性肝炎及慢性肝病的患者。这种症状有时称为“疟疾性肝炎”(malarial hepatitis)[92]。虽然一般认为疟疾性肝炎很少发生,但近年来有逐渐增加的趋势,尤其是在印度和东南亚地区。肝功能不佳的疟疾患者更容易引起并发症,甚至导致死亡[92]。

诊断

编辑由于疟疾没有特定症状,非流行区对于有下列事项的患者须保持警觉:

疟疾的确切诊断必须仰赖血液抹片镜检或特定抗原快速筛检[93][94]。显微镜镜检是最常用的筛检方式,光是2010年,全球就筛检了约1.65亿片血液抹片[95]。然而镜检有两大缺点:首先,许多偏乡并没有筛检器材;其次,镜检的准确率极度依赖检验者的技术以及病人血液中疟原虫的数量。血液抹片镜检的敏感度大约在75-90%之间,最低可能到50%。市面上的快速筛检商品的精准度通常较直接镜检高,但其敏感度及精密度与制造厂商相关,且变动幅度极大。部分地区的快速筛检法必须能分辨出恶性疟,因为其治疗策略和其他种疟疾不同[96];此外,快速筛检法无法检测血液中寄生虫数量[95]。

在拥有疟疾筛检实验室的国家,只要任何进出疫区且身体不适的人,都应该做疟疾筛检。但对于无法负担实验室检查的地区,通常仅按照其发热病史来诊断,因此发热的患者在无法证明是其他疾病之前都会视同疟疾治疗。这种做法造成了疟疾的过度诊断,浪费了大量医疗资源,且滥用的结果可能导致病原体产生抗药性,并可能忽略了非疟疾性发热疾病的控制[97]。虽然现在聚合酶链式反应的技术已经发展出来,但因为操作复杂,截至2012年前并没有广泛用于疫区[9]。

分类

编辑按照世界卫生组织的分类,疟疾分为“重症”(severe)和“轻症”(uncomplicated)两种[9]。只要符合下列标准的任何一项,就属于重症,其余皆属轻症[14]:35。

- 意识减退

- 明显虚弱,例如无法行走

- 无法咽食

- 多处惊厥

- 低血压(成人小于70 mmHg;儿童小于50 mmHg)

- 呼吸困难

- 循环性休克

- 肾功能衰竭或血红蛋白尿

- 出血,或血红素低于50 g/L(5 g/dL)

- 肺水肿

- 血糖低于2.2 mmol/L(40 mg/dL)

- 酸中毒或乳酸浓度高于5 mmol/L。

- 在低流行区血液中寄生虫数高于100,000只/µL;高流行区高于250,000只/µL。

脑疟疾为恶性疟原虫所造成的一系列神经性疾病,患者一律归类为重症。症状包含昏迷(格拉斯哥昏迷量表低于11,或布兰泰尔昏迷量表高于3),或癫痫后昏迷超过30分钟[14]:5。

疟疾会依其性质不同而有不同名字,下表列出疟疾的异名:[98]

| 疾病名称 | 病原体 | 备注 |

|---|---|---|

| 寒冷疟 | 恶性疟原虫 | 重症疟疾影响循环系统,导致发冷及循环性休克。 |

| 黄疸型恶疟 (夏令黄疸热) |

恶性疟原虫 | 重症疟疾影响肝脏,导致呕吐及黄疸 |

| 脑疟疾 | 恶性疟原虫 | 重症疟疾影响大脑,造成一连串神经性症状。 |

| 先天性疟疾 | 多种疟原虫 | 疟原虫游母体垂直传染给胎儿循环系统 |

| 恶性疟 | 恶性疟原虫 | |

| 卵形疟 | 卵形疟原虫 | |

| 三日疟 | 三日疟原虫 | 因发作周期约为三至四日而得名。 |

| 日发疟 | 恶性疟原虫、间日疟原虫 | 因发作周期约为一日而得名。 |

| 间日疟 | 恶性疟原虫、卵形疟原虫、间日疟原虫 | 因其发病周期约为二至三日而得名。 |

| 输血性疟疾 | 多种疟原虫 | 因输血、共用针头,或针扎伤害造成疟疾的感染。 |

| 间日疟 | 间日疟原虫 |

预防

编辑目前为止,对疟疾有效的疫苗是RTS,S。不过疫苗需要配合药物治疗、消灭疟蚊和避免蚊虫叮咬。疟疾需在人蚊之间频繁传播,因此在人口和病媒的高度密集区才能流行;如果去除当中任一项因素,疟疾就会逐渐从此区域消失,就如同北美、欧洲和部分中东地区一样。然而除非疟原虫彻底从世界上消失,疟疾仍有可能再度爆发。此外,人口密度越高,控制疟疾的成本越高,这使得某些地区根本无力负担[99]。

从长期来看,预防比治疗更能节省花费,但大多数贫穷国家无力拿出预防的初始成本。各国在疟疾防治(将疟疾控制在低盛行率)所需要付出的代价差异很大,举例来说,中国政府在2010年宣布消灭疟疾的计划,虽然经费只占其公卫支出的一小部分,2015年中国的疟疾通报人数已降低到只剩3116人[100];然而相似的计划,却需投入坦桑尼亚政府约五分之一的公卫预算[101]。2021年,世界卫生组织确认中国已经消除疟疾[102]

对于疟疾盛行区而言,五岁以下的孩童常会罹有疟疾造成的贫血。给予这些贫血的孩童抗疟药物可些许提升其体内红血球数量,但却无法改变死亡率及住院率[103]。

蚊虫控制

编辑病媒控制是借由降低蚊虫数量来减缓疟疾的传播。个人防治方面可以使用驱虫药,最有效的为待乙妥(DEET)和埃卡瑞丁(picaridin)[104]。在疟疾流行地区,驱虫蚊帐(ITNs)和室内残留喷洒可以有效预防儿童感染[105][106]。及时以青蒿素联合疗法治疗确诊病例也能遏止病原传播[107]

蚊帐

编辑蚊帐可以有效避免蚊虫叮咬,阻断疟疾的传播。但蚊帐有时可能会有破洞或空隙,因此有些蚊帐会以杀虫剂处理,在蚊子找到漏洞前就先将其杀死。驱虫蚊帐的效果是一般蚊帐的两倍,且比起没有挂蚊帐,可以达到70%的保护效果[108]。在2000年到2008年间,驱虫蚊帐的使用已经挽救了大约250,000名南萨哈拉沙漠的幼童生命[109],南萨哈拉约有13%的家户拥有驱虫蚊帐[110]。在2000年,只有约170万(1.8%)名非洲疫区的儿童受到蚊帐保护;到2007年,这个数字遽增到2030万人(18.5%),但还是有8960万名孩童还没受到蚊帐保护[111]。

2008年,已有约31%的非洲家庭拥有驱虫蚊帐,大部分的蚊帐以除虫菊精类处理过,这种杀虫剂毒性较低,从傍晚至黎明时使用效果最好[76]:215。如果可以的话建议使用床帐,才可以确保蚊帐接触到地面,以提供完整防护[112]。

室内残留喷洒

编辑室内残留喷洒即是在家户的墙壁上喷洒杀虫剂。蚊子在吸食完血液之后会停在墙壁上休息,此时残留的杀虫剂就会将其毒死,阻止它去叮咬下一个人[113]。2006年,WHO列了12种室内残留喷洒的建议杀虫剂,包括氟氯氰菊酯、溴氰菊酯等除虫菊精类,以及著名的DDT[114]。由于之前DDT在农业上遭到大量滥用,斯德哥尔摩公约限制DDT仅能用于公共卫生,且有用量管制[53],但此方法已造成许多蚊子产生抗药性。另外,此方法杀死了多数居住于室内的蚊子,选汰的结果导致留存的蚊子不倾向待在室内,因此降低了此方法的效果[115]。

台湾于1953年至1957年间曾进行大规模的室内残留喷洒,病媒蚊短小疟蚊(Anopheles minimus)几乎绝迹。1964年12月,台湾取得当时全球唯一一张疟疾根除证书[116]。自此除1972年北台湾沿海曾出现零星病例、1995年医院内感染及2003年台东两例介入感染外,其余都是境外移入个案。[117]

其他方法

编辑其他用以阻断疟疾传播的蚊虫防治方法有很多,例如清除积水或在特定开放水域施药[118],或使用以高频率声波驱赶母蚊的电子驱蚊设备[119]。

社区参与和卫生教育也能够提升人们对于疟疾防治的认知,这一点某些发展中国家做得相当成功[120]。良好的公卫教育能够促使民众及早就医,增加治疗后的存活率;同时也能指导民众以物品覆盖积水或水缸,阻断疟蚊繁殖。这些教育措施已经在一些人口密集区实施[121]。季节性的流行可以采用间歇式预防措施,此方法已成功地控制女人、幼儿和学龄前学童的疟疾疫情[122][123]。

药物预防

编辑目前已经有一些预防疟疾的药物可以给将前往疫区的人员使用,其中多半也可以用作治疗。氯喹对敏感的疟原虫仍然有效[124],但由于大部分疟原虫对于单一药物已经产生抗药性,因此可能需要采用联合疗法,常用的药物有甲氟喹(mefloquine)、多西环素(Doxycycline)、阿托喹酮(atovaquone)和氯胍盐酸盐(proguanil)[124]。多西环素和阿托喹酮氯胍盐酸盐联合使用对身体影响最小,而甲氟喹则可能导致死亡、自杀倾向和神经与精神症状[124]。

上述药物在服用后无法马上生效,所以前往疫区的人员一般会在行前一两周就开始服药,在离开疫区四周后才停药(阿托喹酮氯胍盐酸盐除外,该药只需在行前两天服用,七天后即可停药)[125]。由于药物价格不菲,在欠发达国家难以买到,且长期服用有副作用,因此预防药物在疫区并没有广泛采用,通常只有孕妇和短期访问的游客才会使用[126],且在疫区使用预防药物会促使疟原虫产生部分抗性[127]。另有研究指出孕妇服用疟疾预防药可以增加婴儿体重并降低贫血风险[128]。

治疗

编辑治疗疟疾的药物称为抗疟药,会依疟疾的种类及严重程度选用不同的药物。虽然抗疟药常会和解热剂一起施用,但效果还不是很明确[129]。

非重症疟疾

编辑非重症的疟疾可以用口服药物治疗,治疗恶性疟最有效的疗法是青蒿素联合疗法(即青蒿素配合其他抗疟药一起服用,简称ACT),它可以减轻疟原虫对单一药物的抗药性[130],能和青蒿素配合的抗疟药包括阿莫地喹(amodiaquine)、本芴醇(lumefantrine)、甲氟喹(mefloquine)或磺胺多辛/乙胺嘧啶 (sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine)[14]:75-86。另一种建议的联合疗法是双氢青蒿素和喹哌(piperaquine)[14]:21[131]。若用在非重症疟疾,青蒿素联合疗法在90%的病例中有效[109];若是治疗孕妇,世界卫生组织建议在怀孕初期(前三个月)用奎宁和克林霉素,在中后期则用青蒿素联合疗法[132]。在2000年左右,东南亚地区已经出现对青蒿素有抗药性的疟疾[133][134]

感染间日疟、卵形疟、或三日疟通常不需住院治疗。治疗间日疟必须同时清除血液和肝脏中的病原体,通常使用氯喹或ACT来清除血液中的病原,而肝脏中的则以伯氨喹(primaquine)治疗[135]。他非诺喹(Tafenoquine)则能防止间日疟复发[136],也可用于根治间日疟感染[137]。

重症疟疾

编辑重症疟疾通常由恶性疟造成,其他种疟原虫一般只会造成较轻微的症状。[138]重症疟疾建议使用静脉注射抗疟药。不论是成人或孩童,青蒿琥酯对重症疟疾的效果都优于奎宁[139];另一份报告指出青蒿素衍生物(包括蒿甲醚和蒿乙醚)对孩童的脑疟疾和奎宁一样有效。[140]。重症疟疾的治疗也包括支持疗法,患者于重症重症监护室中能得到最好的照顾,这包括控制高烧、监控呼吸困难、低血糖和低血钾[69]

抗药性

编辑疟疾的抗药性在21世纪是一个日益严重的问题[141]。目前已知所有的抗疟药都已经出现抗药性,抗药性品系的治疗相当依赖联合疗法,但青蒿素的价格使得发展中国家根本无力负担[142],且目前已知最有效的青蒿素联合疗法也在柬埔寨和泰国的边界地区出现了抗药性品系,使得此种疟疾难以治疗[143]。使用青蒿素单一药物的疗法30多年来,疟原虫长期暴露于此药物,加上许多患者使用了低于标准的剂量,导致抗药性品系的出现[144],目前在柬埔寨、缅甸、泰国、越南、老挝都有发现抗青蒿素的品系[145][146]。

预后

编辑| 无资料 <10 0–100 100–500 500–1000 1000–1500 1500–2000 | 2000–2500 2500–2750 2750–3000 3000–3250 3250–3500 ≥3500 |

一般的疟疾患者在妥善治疗之下通常可以完全康复[147];然而有些重症疟疾的病程进展较为快速,患者可能会在数小时或数天内死亡[148]。最严重的病例即使在良好的治疗与照顾之下,死亡率仍能高达20%[9]。长期影响方面,有文献记载感染过重症疟疾的儿童可能会发育迟缓[149];非重症性的慢性感染也可能导致免疫缺陷,减弱患者对沙门氏菌和EB病毒的抵抗力[150]。

疟疾造成的贫血会对于孩童快速发育的中枢神经造成不良影响,另外病原体也会直接伤害脑疟疾患者的脑部[149],有些脑疟疾患者在痊愈后仍有神经和认知缺陷、行为失调和癫痫等后遗症[151]。临床试验表明服用防疟药能改善认知能力和学习成绩[149]。

流行病学

编辑♦ 氯喹及多重耐药性疟疾高发区

♦ 氯喹抗药性疟疾发生区

♦ 无抗药性及非恶性疟疾发生区

♦ 无疟疾

世卫组织估计2010年全球有2.19亿个疟疾病例,导致66万人死亡[9][153],不过另有估计全球重症疟疾病例有3.5到5.5亿[154],死亡124万人[155],高于1990年的100万人[156]。大多数(65%)的病患为15岁以下的儿童[155]。每年大约1.25亿孕妇有感染的危险,在撒哈拉以南非洲每年有超过20万婴儿因为孕妇感染疟疾而夭折[63]。西欧每年有约一万病例,美国有1300-1500个病例[59]。1993年到2003年间,欧洲有约900人死于疟疾[104]。近几年,全球的发病数和死亡数都有下降的趋势。据WHO和UNICEF的报告,疟疾在2015年的可归因死亡人数从2000年的98.5万减少了60%[157] 。这主要得益于广泛使用喷有杀虫剂的蚊帐和青蒿素联合疗法[109]。2012年,全球有2.07亿人感染疟疾,估计47.3万至78.9万人因此死亡,其中很多是非洲的儿童[2]。非洲自2000年起的抗疟行动已有初步成效,至2015年发生率已减少了40%[158]。

目前的疟疾疫区为一条沿赤道分布的广大带状区域,另中南美洲、亚洲和非洲多地都有流行。其中,在撒哈拉以南非洲的死亡率高达85%至90%[159]。据估计,2009年每十万人口中因疟疾死亡人数最多的地区为科特迪瓦(86.15人)、安哥拉(56.93人)和布基纳法索(50.66人)[160]。2010年的估计显示死亡率最高的国家是布基纳法索、莫桑比克和马里[155]。疟疾地图计划旨在通过描绘全球疟疾流行状况来确定疟疾流行范围,评估疾病负担[161][162],并于2010年发行一张恶性疟原虫的流行地图[163]。截至2015年[update],共有95国家仍为疟疾疫区[164],每年有1.25亿国际游客到过这些国家,超过3万人感染[104]。

在大的疫区里,疟疾的流行分布很复杂,疫区常常紧邻非疫区[165]。疟疾流行于热带和亚热带地区,因为这些地方降水充沛,常年高温高湿,还有蚊子幼虫赖以生长繁殖的积水[166]。在较干旱的地区,通过降雨量可以较为准确地预测疟疾的爆发[167]。相比城市地区,农村地区疟疾更为流行。比如大湄公河次区域中的城市几乎没有疟疾流行,但农村地区,包括国境线以及森林边缘地区就相当流行[168]。相比而言,非洲的城乡地区都有流行,不过大城市的流行风险较低[169]。

社会与文化

编辑经济影响

编辑有证据显示,疟疾不仅由贫困产生,而且还反过来导致贫困,阻碍经济发展[17][18]。虽然疟疾疫区主要位于热带,四季分明的温带地区也会受到疫情波及。疟疾给这些地区的经济造成不利影响。从19世纪下半叶至20世纪下半叶,疟疾也阻碍了美国南方的经济发展[170]。

1995年,无疟疾的国家平均GDP(按购买力平价)为8268美元,是有疟疾的国家平均GDP(1568美元)的5倍。从1965年至1990年,无疟疾的国家人均GDP年均增长2.4%,而有疟疾的国家增长率只有0.4%[171]。

贫困会增加疟疾患病率,因为贫穷人口无力负担防控成本。疟疾在整个非洲已经造成每年120亿美元的经济损失,其中包括医疗成本、病假、失学、脑疟疾导致的生产力下降,还有投资和旅游业的损失[23]。疟疾已给部分国家带来沉重负担,包括30%至50%的住院患者,50%的门诊患者和高达40%的公共卫生开支[172]。

脑疟疾是非洲儿童神经系统残疾的主因[151]。研究表明即使从疟疾中康复,学习成绩也会大受影响[149],所以重症脑疟疾的社会经济成本远远不止于疾病本身[173]。

伪劣药品

编辑柬埔寨[174]、中国[175]、印尼、老挝、泰国和越南等亚洲国家已经出现高仿真的假抗疟药,并造成不必要的死亡[176]。世卫组织说40%的青蒿琥酯类抗疟药都是假的,在大湄公河地区情况更糟。世卫组织已经建立了一套快速向有关部门报告假药的预警系统[177]。假药只能在实验室里检验出来。制药公司正努力开发新技术以从源头和销售上杜绝假药[178]。

另一公共卫生问题是劣质药品泛滥。劣质药品往往含量不足、受到污染、原料不合格、稳定性差、包装不合规[179]。2012年的研究显示,东南亚和撒哈拉以南非洲大约三分之一的抗疟药为化学成分或包装不合格的伪劣药品[180]。

疟疾和战争

编辑历史上,疟疾在政治和军事中扮演着重要角色[181]。1910年诺贝尔医学奖得主罗纳德·罗斯(他自己就是疟疾生还者)发表了著作《疟疾的预防》,其中有一章题为“战争中疟疾的预防”。这章的作者,皇家军医学院(Royal Army Medical College)卫生学教授梅尔维尔(Colonel C. H. Melville)这样描述疟疾在历次战争中的影响:“疟疾几乎贯穿了整个战争史,至少是公元后的战争史……很多十六至十八世纪战地军营中出现的发热疫情,其元凶可能都是疟疾。”[182]

二战期间,疟疾是美军在南太平洋面临的最大健康威胁,约有50万士兵遭到感染[183]。澳大利亚政治家约瑟夫·帕特里克·拜恩说:“非洲和南太平洋战场上有6万美军士兵死于疟疾。”[184]

购买现有抗疟药和研发新药已花掉了巨额经费。在一战和二战中,金鸡纳树树皮和奎宁等天然抗疟药的供应无法保证,促使大量经费用于其他药物和疫苗的研发。美国相应的研究机构有海军医学研究中心、沃尔特·里德陆军研究院、美国陆军传染病医学研究院[185]。

另外,1942年美国战争地区疟疾控制办公室(Malaria Control in War Areas,缩写MCWA)成立,以控制美国南方地区军事训练基地中的疟疾疫情。该办公室于1946年变更为传播疾病中心(Communicable Disease Center),即现在的美国疾病控制与预防中心[186]。

防疫工作

编辑全球有数个旨在消除疟疾的组织。2006年,公益组织“消灭疟疾”(Malaria No More)定下目标,准备在2015年前消除非洲的疟疾,目标达成就解散[187]。已有数种旨在保护疫区儿童,减缓疫情扩散的疟疾疫苗正在进行临床试验。截至2015年[update],全球防治艾滋病、结核病和疟疾基金(The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria)已经分发5.48亿顶喷洒有杀虫剂的蚊帐以阻止蚊子传播疟疾[188]。美国克林顿基金会努力维持青蒿素市场价格稳定,保障市场需求[189]。其他诸如疟疾地图计划等项目则致力于分析气候环境资讯,评估病媒蚊的栖息地情况,从而准确预测疫情[161]。隶属世卫组织的疟疾政策咨询委员会(Malaria Policy Advisory Committee,缩写MPAC)2012年成立,旨在为控制和消除疟疾提供全方面的战略咨询和技术帮助[190]。2013年11月,世卫组织和疟疾疫苗资助者群组(the Malaria Vaccine Funders Group)定下目标开发阻断疟疾传播的疫苗,争取最终消灭疟疾[191]。

一些地区的疟疾疫情已经消除或大为缓解。美国和欧洲南部的疟疾一度非常流行,但病媒控制和对患者的监视治疗已经消灭了这些地区的疟疾。这得益于水管理方式的改善(如排干农田湿地,阻止孑孓繁殖)和卫生措施的进步(如给居室装上玻璃窗和纱窗)[192]。这样到了20世纪早期,美国大部分地区已经消灭了疟疾,个别南方地区在使用杀虫剂DDT后也在50年代消灭了疟疾[193]。全球疟疾根除计划从1955年开始倡导三管齐下的防治方法:用DDT和室内喷洒控制病媒,经常采集人群的血液涂片以了解流行状况,以及对受感染的患者提供化学疗法。该计划使苏里南的首都和沿海城市消灭了疟疾[194]。1994年到2010年期间,不丹采取了积极的防控策略,使确诊病例减少了98.7%。除了在疫区用室内残留喷洒,发放耐用蚊帐等方式控制病媒外,经济的发展和卫生服务的普及也减少了不丹的疟疾发病数[195]。

研究

编辑疫苗

编辑人体可以自然对于恶性疟原虫产生免疫力(或者说免疫耐受),但只有在数年多次感染后才会产生[82]。有研究发现,X光可以使子孢子失去感染力[196],但必须被蚊子叮咬约一千次才能产生足够抵抗力,无法全面应用[197][198]。

恶性疟原虫蛋白质的多态性造成疫苗开发相当困难,至今仍然尚未开发出可上市的蛋白质疟疾疫苗[199]。疟疾疫苗的候选抗原来自于疟原虫生活史的各阶段,包含疟原虫的配子体、受精卵,以及蚊子中肠里的卵动子。疫苗可以促使个体对这些抗原产生抗体,当蚊子吸取人血时,血液中的抗体可以阻断疟原虫在蚊子体内的生活史[200]。

另一类疫苗则是针对血液其产生的抗原,可惜目前皆成效不彰[201]。例如1990年代,由于疟疾盛行,SPf66在各地区密集测试,然而效果并不理想[202]。还有一类疫苗是针对前红血球时期,此类疫苗抗原目前以RTS,S成为第一个由世界卫生组织认可的疟疾疫苗[203][204]。

美国生物技术公司Sanaria正在开发一种针对前红血球时期的减毒疫苗,称为PfSPZ。这种疫苗是利用完整的子孢子来诱发免疫反应[205]。2006年,世界卫生组织疟疾疫苗咨询委员会发表“疟疾疫苗技术发展蓝图”,提到2015年其中一项重要目标是“发展第一代核准疟疾疫苗,其对于重症疟疾之效力须达50%,且至少维持一年。”[206]

2021年10月6日,世界卫生组织建议在撒哈拉以南非洲和其他饱受疟疾肆虐之苦地区的儿童接种疟疾疫苗(RTS,S/AS01)[207]。

药物治疗

编辑疟原虫体内具有顶复器,这是一种类似植物质粒体(包括叶绿体)的胞器,由于顶复器带有自己的基因体,因此有研究认为顶复器来自于疟原虫与藻类的二次内共生。顶复器对于疟原虫的新陈代谢(如脂肪酸合成)相当重要。顶复器制造了逾400种蛋白质,目前正研究是否可能以这些蛋白质作为标靶,来设计抗疟药物[208]。

耐药性疟原虫的出现促使人们研发新的对抗疟疾的方法,例如让疟原虫吸收吡哆醛—氨基酸加合物,以阻碍其必需的维生素B的生成[209][210]。含有有机金属配合物的合成抗疟药亦颇受研究者们青睐[211][212]。

另一大类试验中的药物是螺环吲哚酮药物,为ATP4疟原虫蛋白的抑制剂[213]。这类药物可将受感染红血球的钠平衡破坏,使之老化皱缩。在小鼠身上,这类药物可以成功引起免疫系统清除受感染细胞。2014年,霍华德·休斯医学研究所已开始就这类药物中的(+)-SJ733[213],在人体中进行第一期人体试验[214]。同类药物还有NITD246[214]和NITD609[215],同样也是以ATP4为作用目标。

遗传学

编辑控制病媒的方法除了化学方法之外,现在还有使用基因工程的做法。基因体是疟疾研究的中心,目前恶性疟原虫、病媒蚊冈比亚疟蚊,和人类的基因体皆已定序[216]。科学家改造疟蚊的基因,使其寿命缩短,或是可以抵御疟疾。昆虫不育技术则是释放大量去势的雄蚊,使之与雌蚊交配,以减少子代数量。重复操作可以达到灭绝特定族群的目的[108]。另一种作法则是释放基因改造的蚊子,使其无法感染疟疾,达到生物控制的效果[217]。

其他动物

编辑目前为止已发现有将近200种疟原虫可以感染鸟类、爬虫类和其他哺乳类[218],有大约30种会感染人类以外的灵长类[219]。有些感染非人类灵长类的疟原虫可作为模式生物,例如柯氏疟原虫(P. coatneyi,为恶性疟原虫的模式生物)和食蟹猴疟原虫(P. cynomolgi,为间日疟原虫的模式生物),在非人灵长类身上诊断疟原虫的方式与人类相似[220]。感染啮齿类的疟原虫也常常用作模式生物研究,例如伯氏疟原虫(P. berghei)[221]。

鸟疟疾的宿主通常是雀形目的鸟类,此种疟疾给夏威夷、加拉巴哥群岛和一些其他岛屿的鸟类带来严重威胁。已发现残疟原虫(P. relictum)会影响夏威夷特有鸟类的分布与数量。全球暖化给予了疟原虫更适宜的生活环境,届时可能会造成鸟疟疾更加肆虐[222]。

参见

编辑注释

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Caraballo H. Emergency department management of mosquito-borne illness: Malaria, dengue, and west nile virus. Emergency Medicine Practice. 2014, 16 (5). (原始内容存档于2016-08-12).

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Malaria Fact sheet N°94. WHO. 2014-03 [2014-08-28]. (原始内容存档于2016-07-18).

- ^ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.. Lancet. 2016-10-08, 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMC 5055577 . PMID 27733282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6.

- ^ GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.. Lancet. 2016-10-08, 388 (10053): 1459–1544. PMID 27733281. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1.

- ^ 果君 (编). 忽冷忽热“打摆子” 科学认识“疟疾”的真面目. 央广网. 2020-04-24 [2023-01-26]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-26).

- ^ 教育部重編國語辭典修訂本-瘧疾. 中华民国教育部. [2016-07-31]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-22).

- ^ 非洲、东南亚旅游谨防“疟疾”. 石家庄日报. 2016-05-03: C07 [2017-01-09]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-09).

- ^ Burchard G-D. Fieber nach Tropenaufenthalt. Malaria ist die wichtigste Differenzialdiagnose. Pharmazie in Unserer Zeit. 2010, 39 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1002/pauz.201000349.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Nadjm B, Behrens RH. Malaria: An update for physicians. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2012, 26 (2): 243–59. PMID 22632637. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.010.

- ^ Schlagenhauf P1, Haller S, Wagner N, Chappuis F. Malaria und Kinder, die reisen – Prophylaxe und Therapie. Therapeutische Umschau. 2013, 70 (6): 323–33. PMID 23732448. doi:10.1024/0040-5930/a000411.

- ^ Casuccio A, Immordino P. Il ruolo dei visiting friends and relatives (VFRs) nella malaria da importazione: revisione della letteratura. Epidemiologia e prevenzione. 2014, 38 (6 Suppl 2): 23–8.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015. The Nobel Foundation. [2016-08-03]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-21).

- ^ Drysdale C, Kelleher K. WHO recommends groundbreaking malaria vaccine for children at risk (新闻稿). Geneva: World Health Organization. [2021-10-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-07).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 WHO. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria (PDF) (报告) 2nd. World Health Organization. 2010. ISBN 978-9-2415-4792-5. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-05-20).

- ^ Koenderink JB1, Kavishe RA, Rijpma SR, Russel FG. The ABCs of multidrug resistance in malaria.. Trends in Parasitology. 2010, 26 (9): 440–6. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2010.05.002.

- ^ Hofmann M. Malaria: Der Feind aus den Tropen – entlarvt und bekämpft. Diplomica Verlag. 2015: 6 [2015-08-19]. ISBN 978-3-958-50791-3. (原始内容存档于2016-06-23).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Gollin D, Zimmermann C. Malaria: Disease Impacts and Long-Run Income Differences (PDF) (报告). Institute for the Study of Labor. 2007-08. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-18).

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Worrall E, Basu S, Hanson K. Is malaria a disease of poverty? A review of the literature. Tropical Health and Medicine. 2005, 10 (10): 1047–59. PMID 16185240. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01476.x.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014-12-17, 385 (9963): 117–171 [2015-05-20]. PMC 4340604 . PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. (原始内容存档于2018-01-26).

- ^ Factsheet on the World Malaria Report 2014. World Health Orgnization. 2014 [2015-02-02]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-28).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Malaria Fact sheet N°94. WHO. [2016-02-02]. (原始内容存档于2014-09-03).

- ^ WHO. World Malaria Report 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2014: 32–42. ISBN 978-92-4156483-0.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Greenwood BM, Bojang K, Whitty CJ, Targett GA. Malaria. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9469): 1487–98. PMID 15850634. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66420-3.

- ^ Harper K, Armelagos G. The changing disease-scape in the third epidemiological transition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011, 7 (2): 675–97. PMC 2872288 . PMID 20616997. doi:10.3390/ijerph7020675.

- ^ Prugnolle F, Durand P, Ollomo B, Duval L, Ariey F, Arnathau C, Gonzalez JP, Leroy E, Renaud F. Manchester, Marianne , 编. A fresh look at the origin of Plasmodium falciparum, the most malignant malaria agent. PLoS Pathogens. 2011, 7 (2): e1001283. PMC 3044689 . PMID 21383971. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001283.

- ^ Cox F. History of human parasitology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2002, 15 (4): 595–612. PMC 126866 . PMID 12364371. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.4.595-612.2002.

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Strong, Richard P. Stitt's Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment of Tropical Diseases Seventh. York, PA: The Blakiston company. 1944 [2015-03-08].

- ^ 羅馬帝國也有瘧疾,首度由 DNA 確認. GeneOnline News. 2016-12-14 [2018-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2018-12-09) (中文(台湾)).

- ^ Sallares R. Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy. Oxford University Press. 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-924850-6. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199248506.001.0001.

- ^ DNA clues to malaria in ancient Rome. BBC News. 2001-02-20 [2015-05-20]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-20)., in reference to Sallares R, Gomzi S. Biomolecular archaeology of malaria. Ancient Biomolecules. 2001, 3 (3): 195–213. OCLC 538284457.

- ^ Hays JN. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. 2005: 11 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-1-85109-658-9. (原始内容存档于2016-05-02).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 32.2 孟小燕; 王育林. 上古文献中疟疾病证名单音词研究. 中医文献杂志. 2016, 34 (3): 22–25. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1006-4737.2016.03.008.

- ^ Reiter, P. From Shakespeare to Defoe: malaria in England in the Little Ice Age.. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1999, 6 (1): 1–11 [2015-05-20]. PMC 2627969 . PMID 10653562. doi:10.3201/eid0601.000101. (原始内容存档于2015-04-05).

- ^ Lindemann M. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. 1999: 62 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-0-521-42354-0. (原始内容存档于2016-04-26).

- ^ Gratz NG, World Health Organization. The Vector- and Rodent-borne Diseases of Europe and North America: Their Distribution and Public Health Burden. Cambridge University Press. 2006: 33 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-0-521-85447-4. (原始内容存档于2016-06-29).

- ^ Webb Jr JLA. Humanity's Burden: A Global History of Malaria. Cambridge University Press. 2009 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-0-521-67012-8. (原始内容存档于2016-04-27).

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1907: Alphonse Laveran. The Nobel Foundation. [2012-05-14]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-14).

- ^ Tan SY, Sung H. Carlos Juan Finlay (1833–1915): Of mosquitoes and yellow fever (PDF). Singapore Medical Journal. 2008, 49 (5): 370–1 [2015-05-20]. PMID 18465043. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2008-07-23).

- ^ Chernin E. Josiah Clark Nott, insects, and yellow fever. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1983, 59 (9): 790–802. PMC 1911699 . PMID 6140039.

- ^ Chernin E. Patrick Manson (1844–1922) and the transmission of filariasis. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1977, 26 (5 Pt 2 Suppl): 1065–70. PMID 20786.

- ^ 41.0 41.1 The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1902: Ronald Ross. The Nobel Foundation. [2012-05-14]. (原始内容存档于2012-04-29).

- ^ Ross and the Discovery that Mosquitoes Transmit Malaria Parasites. CDC Malaria website. [2012-06-14]. (原始内容存档于2007-06-02).

- ^ Simmons JS. Malaria in Panama. Ayer Publishing. 1979 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-0-405-10628-6. (原始内容存档于2016-05-21).

- ^ Kaufman TS, Rúveda EA. The quest for quinine: Those who won the battles and those who won the war. Angewandte Chemie (International Edition in English). 2005, 44 (6): 854–85. PMID 15669029. doi:10.1002/anie.200400663.

- ^ Pelletier PJ, Caventou JB. Des recherches chimiques sur les Quinquinas [Chemical research on quinquinas]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 1820, 15: 337–65 [2015-05-20]. (原始内容存档于2014-07-01) (法语).

- ^ Kyle R, Shampe M. Discoverers of quinine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1974, 229 (4): 462. PMID 4600403. doi:10.1001/jama.229.4.462.

- ^ Achan J, Talisuna AO, Erhart A, Yeka A, Tibenderana JK, Baliraine FN, Rosenthal PJ, D'Alessandro U. Quinine, an old anti-malarial drug in a modern world: Role in the treatment of malaria. Malaria Journal. 2011, 10 (1): 144 [2015-05-20]. PMC 3121651 . PMID 21609473. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-144. (原始内容存档于2012-02-26).

- ^ Hsu E. Reflections on the 'discovery' of the antimalarial qinghao. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2006, 61 (3): 666–70. PMC 1885105 . PMID 16722826. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02673.x.

- ^ Nobel Prize announcement (PDF). NobelPrize.org. [2015-10-05]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-01-06).

- ^ Vogel V. Malaria as a lifesaving therapy. Science. 2013, 342 (6159): 684–7. doi:10.1126/science.342.6159.684.

- ^ Killeen G, Fillinger U, Kiche I, Gouagna L, Knols B. Eradication of Anopheles gambiae from Brazil: Lessons for malaria control in Africa?. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2002, 2 (10): 618–27. PMID 12383612. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00397-3.

- ^ Eradication of Malaria in the United States (1947–1951). US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010-02-08 [2012-05-02]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-04).

- ^ 53.0 53.1 van den Berg H. Global status of DDT and its alternatives for use in vector control to prevent disease. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009, 117 (11): 1656–63. PMC 2801202 . PMID 20049114. doi:10.1289/ehp.0900785.

- ^ Vanderberg JP. Reflections on early malaria vaccine studies, the first successful human malaria vaccination, and beyond. Vaccine. 2009, 27 (1): 2–9. PMC 2637529 . PMID 18973784. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.028.

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Fairhurst RM, Wellems TE. Chapter 275. Plasmodium species (malaria). Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R (eds) (编). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases 2 7th. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2010: 3437–62. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 Bartoloni A, Zammarchi L. Clinical aspects of uncomplicated and severe malaria. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2012, 4 (1): e2012026. PMC 3375727 . PMID 22708041. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2012.026.

- ^ Beare NA, Taylor TE, Harding SP, Lewallen S, Molyneux ME. Malarial retinopathy: A newly established diagnostic sign in severe malaria. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006, 75 (5): 790–7. PMC 2367432 . PMID 17123967.

- ^ Ferri FF. Chapter 332. Protozoal infections. Ferri's Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009: 1159 [2016-07-31]. ISBN 978-1-4160-4919-7. (原始内容存档于2016-08-21).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 Taylor WR, Hanson J, Turner GD, White NJ, Dondorp AM. Respiratory manifestations of malaria. Chest. 2012, 142 (2): 492–505. PMID 22871759. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2655.

- ^ Korenromp E, Williams B, de Vlas S, Gouws E, Gilks C, Ghys P, Nahlen B. Malaria attributable to the HIV-1 epidemic, sub-Saharan Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005, 11 (9): 1410–9 [2015-05-20]. PMC 3310631 . PMID 16229771. doi:10.3201/eid1109.050337. (原始内容存档于2011-06-29).

- ^ Beare NA, Lewallen S, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME. Redefining cerebral malaria by including malaria retinopathy. Future Microbiology. 2011, 6 (3): 349–55. PMC 3139111 . PMID 21449844. doi:10.2217/fmb.11.3.

- ^ {{cite book|last1=Walker|first1= Brian R|last2=Colledge|first2= Nicki R|title=Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine|date=2013|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|edition=21|page=351|isbn= 0702030856}

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Hartman TK, Rogerson SJ, Fischer PR. The impact of maternal malaria on newborns. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 2010, 30 (4): 271–82. PMID 21118620. doi:10.1179/146532810X12858955921032.

- ^ Rijken MJ, McGready R, Boel ME, Poespoprodjo R, Singh N, Syafruddin D, Rogerson S, Nosten F. Malaria in pregnancy in the Asia-Pacific region. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012, 12 (1): 75–88. PMID 22192132. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70315-2.

- ^ 65.0 65.1 杜文圆. 醫用寄生蟲學手冊. 艺轩. ISBN 957-616-442-7.

- ^ Mueller I, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC. Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale—the "bashful" malaria parasites. Trends in Parasitology. 2007, 23 (6): 278–83. PMC 3728836 . PMID 17459775. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2007.04.009.

- ^ Collins WE. Plasmodium knowlesi: A malaria parasite of monkeys and humans. Annual Review of Entomology. 2012, 57: 107–21. PMID 22149265. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-121510-133540.

- ^ Arnott A, Barry AE, Reeder JC. Understanding the population genetics of Plasmodium vivax is essential for malaria control and elimination. Malaria Journal. 2012, 11: 14. PMC 3298510 . PMID 22233585. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-14.

- ^ 69.0 69.1 Sarkar PK, Ahluwalia G, Vijayan VK, Talwar A. Critical care aspects of malaria. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2009, 25 (2): 93–103. PMID 20018606. doi:10.1177/0885066609356052.

- ^ Baird JK. Evidence and implications of mortality associated with acute Plasmodium vivax malaria. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2013, 26 (1): 36–57. PMC 3553673 . PMID 23297258. doi:10.1128/CMR.00074-12.

- ^ Collins WE, Barnwell JW. Plasmodium knowlesi: finally being recognized. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009, 199 (8): 1107–8. PMID 19284287. doi:10.1086/597415.

- ^ {凯瑟琳‧麦考利夫. 寄生大脑:病毒、细菌、寄生虫如何影响人类行为与社会.台北市: 木马文化.2020年6月: 52. ISBN 978-986-359-787-2}

- ^ Zhang, Qian; Lai, Shengjie; Zheng, Canjun; Zhang, Honglong; Zhou, Sheng; Hu, Wenbiao; Clements, Archie CA; Zhou, Xiao-Nong; Yang, Weizhong; Hay, Simon I; Yu, Hongjie; Li, Zhongjie. The epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria in China, 2004–2012: from intensified control to elimination. Malaria Journal. 2014, 13 (1): 419. ISSN 1475-2875. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-419.

- ^ Parham PE, Christiansen-Jucht C, Pople D, Michael E. Understanding and modelling the impact of climate change on infectious diseases. Blanco J, Kheradmand H (eds.) (编). Climate Change – Socioeconomic Effects. 2011: 43–66 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-9533074115. (原始内容存档于2014-03-13).

- ^ Climate Change And Infectious Diseases (PDF). CLIMATE CHANGE AND HUMAN HEALTH — RISK AND RESPONSES. World Health Organization. [2015-05-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-03-04).

- ^ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Schlagenhauf-Lawlor P. Travelers' Malaria. PMPH-USA. 2008 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-1-55009-336-0. (原始内容存档于2016-05-12).

- ^ Cowman AF, Berry D, Baum J. The cellular and molecular basis for malaria parasite invasion of the human red blood cell. Journal of Cell Biology. 2012, 198 (6): 961–71. PMC 3444787 . PMID 22986493. doi:10.1083/jcb.201206112.

- ^ Josling GLlinás M. Sexual development in Plasmodium parasites: knowing when it's time to commit.. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2015, 13 (9): 573–587. PMID 26272409. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3519.

- ^ Owusu-Ofori AK, Parry C, Bates I. Transfusion-transmitted malaria in countries where malaria is endemic: A review of the literature from sub-Saharan Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010, 51 (10): 1192–8. PMID 20929356. doi:10.1086/656806.

- ^ Chen, Kow‐Tong; Chen, Chein‐Jen; Chang, Po‐Ya; Morse, Dale L. A Nosocomial Outbreak of Malaria Associated With Contaminated Catheters and Contrast Medium of a Computed Tomographic Scanner • . Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 1999, 20 (1): 22–25. ISSN 0899-823X. doi:10.1086/501557.

- ^ 81.0 81.1 White NJ. Determinants of relapse periodicity in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Malaria Journal. 2011, 10: 297. PMC 3228849 . PMID 21989376. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-297.

- ^ 82.0 82.1 Tran TM, Samal B, Kirkness E, Crompton PD. Systems immunology of human malaria. Trends in Parasitology. 2012, 28 (6): 248–57. PMC 3361535 . PMID 22592005. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.03.006.

- ^ Vaughan AM, Aly AS, Kappe SH. Malaria parasite pre-erythrocytic stage infection: Gliding and hiding. Cell Host & Microbe. 2008, 4 (3): 209–18. PMC 2610487 . PMID 18779047. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.010.

- ^ 84.0 84.1 Bledsoe GH. Malaria primer for clinicians in the United States. Southern Medical Journal. 2005, 98 (12): 1197–204; quiz 1205, 1230 [2015-07-05]. PMID 16440920. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000189904.50838.eb. (原始内容存档于2016-03-06).

- ^ Richter J, Franken G, Mehlhorn H, Labisch A, Häussinger D. What is the evidence for the existence of Plasmodium ovale hypnozoites?. Parasitology Research. 2010, 107 (6): 1285–90. PMID 20922429. doi:10.1007/s00436-010-2071-z.

- ^ Tilley L, Dixon MW, Kirk K. The Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cell. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2011, 43 (6): 839–42. PMID 21458590. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2011.03.012.

- ^ Mens PF, Bojtor EC, Schallig HDFH. Molecular interactions in the placenta during malaria infection. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2012, 152 (2): 126–32. PMID 20933151. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.05.013.

- ^ Rénia L, Wu Howland S, Claser C, Charlotte Gruner A, Suwanarusk R, Hui Teo T, Russell B, Ng LF. Cerebral malaria: mysteries at the blood-brain barrier. Virulence. 2012, 3 (2): 193–201. PMC 3396698 . PMID 22460644. doi:10.4161/viru.19013.

- ^ Kwiatkowski DP. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005, 77 (2): 171–92. PMC 1224522 . PMID 16001361. doi:10.1086/432519.

- ^ 90.0 90.1 Hedrick PW. Population genetics of malaria resistance in humans. Heredity. 2011, 107 (4): 283–304. PMC 3182497 . PMID 21427751. doi:10.1038/hdy.2011.16.

- ^ Weatherall DJ. Genetic variation and susceptibility to infection: The red cell and malaria. British Journal of Haematology. 2008, 141 (3): 276–86. PMID 18410566. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07085.x.

- ^ 92.0 92.1 Bhalla A, Suri V, Singh V. Malarial hepatopathy. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2006, 52 (4): 315–20 [2015-05-20]. PMID 17102560. (原始内容存档于2013-09-21).

- ^ Abba K, Deeks JJ, Olliaro P, Naing CM, Jackson SM, Takwoingi Y, Donegan S, Garner P. Abba, Katharine , 编. Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in endemic countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011, (7): CD008122. PMID 21735422. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008122.pub2.

- ^ Kattenberg JH, Ochodo EA, Boer KR, Schallig HD, Mens PF, Leeflang MM. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Rapid diagnostic tests versus placental histology, microscopy and PCR for malaria in pregnant women. Malaria Journal. 2011, 10: 321. PMC 3228868 . PMID 22035448. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-321.

- ^ 95.0 95.1 Wilson ML. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012, 54 (11): 1637–41. PMID 22550113. doi:10.1093/cid/cis228.

- ^ Abba, Katharine; Kirkham, Amanda J; Olliaro, Piero L; Deeks, Jonathan J; Donegan, Sarah; Garner, Paul; Takwoingi, Yemisi. Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated non-falciparum or Plasmodium vivax malaria in endemic countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd). 2014-12-18, 12: CD011431 [2016-05-03]. PMC 4453861 . PMID 25519857. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011431. (原始内容存档于2017-01-26).

- ^ Perkins MD, Bell DR. Working without a blindfold: The critical role of diagnostics in malaria control. Malaria Journal. 2008, 1 (Suppl 1): S5. PMC 2604880 . PMID 19091039. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-7-S1-S5.

- ^ Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier, [2016-08-07], (原始内容存档于2014-01-11).

- ^ World Health Organization. Malaria. The First Ten Years of the World Health Organization (PDF). World Health Organization. 1958: 172–87 [2011-10-06]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-08).

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 2015年全國法定傳染病疫情概況. 中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 2016-02-18 [2016-08-16]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-04).

- ^ Sabot O, Cohen JM, Hsiang MS, Kahn JG, Basu S, Tang L, Zheng B, Gao Q, Zou L, Tatarsky A, Aboobakar S, Usas J, Barrett S, Cohen JL, Jamison DT, Feachem RG. Costs and financial feasibility of malaria elimination. Lancet. 2010, 376 (9752): 1604–15. PMC 3044845 . PMID 21035839. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61355-4.

- ^ 刘曲. 世卫组织向中国颁发国家消除疟疾认证. 新华社. 2021-06-30 [2021-06-30]. (原始内容存档于2021-07-27) (中文(中国大陆)).

- ^ Athuman, M; Kabanywanyi, AM; Rohwer, AC. Intermittent preventive antimalarial treatment for children with anaemia.. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015-01-13, 1: CD010767. PMC 4447115 . PMID 25582096. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010767.pub2.

- ^ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Kajfasz P. Malaria prevention. International Maritime Health. 2009, 60 (1–2): 67–70. PMID 20205131.

- ^ Lengeler C. Lengeler, Christian , 编. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004, (2): CD000363. PMID 15106149. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000363.pub2.

- ^ Tanser FC, Lengeler C, Sharp BL. Lengeler, Christian , 编. Indoor residual spraying for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010, (4): CD006657. PMID 20393950. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006657.pub2.

- ^ Palmer, J. WHO gives indoor use of DDT a clean bill of health for controlling malaria. WHO. [2015-05-20]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-11).

- ^ 108.0 108.1 Raghavendra K, Barik TK, Reddy BP, Sharma P, Dash AP. Malaria vector control: From past to future. Parasitology Research. 2011, 108 (4): 757–79. PMID 21229263. doi:10.1007/s00436-010-2232-0.[永久失效链接]

- ^ 109.0 109.1 109.2 Howitt P, Darzi A, Yang GZ, Ashrafian H, Atun R, Barlow J, Blakemore A, Bull AM, Car J, Conteh L, Cooke GS, Ford N, Gregson SA, Kerr K, King D, Kulendran M, Malkin RA, Majeed A, Matlin S, Merrifield R, Penfold HA, Reid SD, Smith PC, Stevens MM, Templeton MR, Vincent C, Wilson E. Technologies for global health. The Lancet. 2012, 380 (9840): 507–35. PMID 22857974. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61127-1.

- ^ Miller JM, Korenromp EL, Nahlen BL, W Steketee R. Estimating the number of insecticide-treated nets required by African households to reach continent-wide malaria coverage targets. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007, 297 (20): 2241–50. PMID 17519414. doi:10.1001/jama.297.20.2241.

- ^ Noor AM, Mutheu JJ, Tatem AJ, Hay SI, Snow RW. Insecticide-treated net coverage in Africa: Mapping progress in 2000–07. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9657): 58–67. PMC 2652031 . PMID 19019422. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61596-2.

- ^ Instructions for treatment and use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (PDF). World Health Organization. 2002: 34. (原始内容 (pdf)存档于2015-07-06).

- ^ Enayati A, Hemingway J. Malaria management: Past, present, and future. Annual Review of Entomology. 2010, 55: 569–91. PMID 19754246. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085423.

- ^ Indoor Residual Spraying: Use of Indoor Residual Spraying for Scaling Up Global Malaria Control and Elimination. WHO Position Statement (PDF) (报告). World Health Organization. 2006. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-01-22).

- ^ Pates H, Curtis C. Mosquito behaviour and vector control. Annual Review of Entomology. 2005, 50: 53–70. PMID 15355233. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130439.

- ^ W. I. Chen. Malaria eradication in Taiwan, 1952-1964--some memorable facts.. 高雄医学科学杂志. 1991年5月, 5 (7): 263–270. PMID 2056560.

- ^ 瘧疾. 卫生福利部疾病管制署. [2018-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-24) (中文(台湾)).

- ^ Tusting LS, Thwing J, Sinclair D, Fillinger U, Gimnig J, Bonner KE, Bottomley C, Lindsay SW. Mosquito larval source management for controlling malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013, 8: CD008923. PMID 23986463. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008923.pub2.

- ^ Enayati AA, Hemingway J, Garner P. Enayati, Ahmadali , 编. Electronic mosquito repellents for preventing mosquito bites and malaria infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007, (2): CD005434 [2015-07-05]. PMID 17443590. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005434.pub2. (原始内容存档于2016-03-06).

- ^ Lalloo DG, Olukoya P, Olliaro P. Malaria in adolescence: Burden of disease, consequences, and opportunities for intervention. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2006, 6 (12): 780–93. PMID 17123898. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70655-7.

- ^ Mehlhorn H (编). Disease Control, Methods. Encyclopedia of Parasitology 3rd. Springer: 362–6. 2008. ISBN 978-3-540-48997-9.

- ^ Meremikwu MM, Donegan S, Sinclair D, Esu E, Oringanje C. Meremikwu, Martin M , 编. Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in children living in areas with seasonal transmission. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012, 2 (2): CD003756. PMID 22336792. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003756.pub4.

- ^ Bardají A, Bassat Q, Alonso PL, Menéndez C. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnant women and infants: making best use of the available evidence. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2012, 13 (12): 1719–36. PMID 22775553. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.703651.

- ^ 124.0 124.1 124.2 Jacquerioz FA, Croft AM. Jacquerioz FA , 编. Drugs for preventing malaria in travellers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009, (4): CD006491. PMID 19821371. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006491.pub2.

- ^ Freedman DO. Clinical practice. Malaria prevention in short-term travelers. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008, 359 (6): 603–12 [2015-05-20]. PMID 18687641. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0803572. (原始内容存档于2012-04-22).

- ^ Fernando SD, Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. Chemoprophylaxis in malaria: Drugs, evidence of efficacy and costs. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011, 4 (4): 330–6. PMID 21771482. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60098-9.

- ^ Turschner S, Efferth T. Drug resistance in Plasmodium: Natural products in the fight against malaria. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2009, 9 (2): 206–14. PMID 19200025. doi:10.2174/138955709787316074.

- ^ Radeva-Petrova, D; Kayentao, K; Ter Kuile, FO; Sinclair, D; Garner, P. Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women in endemic areas: any drug regimen versus placebo or no treatment.. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014-10-10, 10: CD000169. PMID 25300703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000169.pub3.

- ^ Meremikwu MM, Odigwe CC, Akudo Nwagbara B, Udoh EE. Meremikwu, Martin M , 编. Antipyretic measures for treating fever in malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012, 9: CD002151. PMID 22972057. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002151.pub2.

- ^ Kokwaro G. Ongoing challenges in the management of malaria. Malaria Journal. 2009, 8 (Suppl 1): S2. PMC 2760237 . PMID 19818169. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-8-S1-S2.

- ^ Keating GM. Dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine: A review of its use in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Drugs. 2012, 72 (7): 937–61. PMID 22515619. doi:10.2165/11203910-000000000-00000.

- ^ Manyando C, Kayentao K, D'Alessandro U, Okafor HU, Juma E, Hamed K. A systematic review of the safety and efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine against uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria during pregnancy. Malaria Journal. 2011, 11: 141. PMC 3405476 . PMID 22548983. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-141.

- ^ O'Brien C, Henrich PP, Passi N, Fidock DA. Recent clinical and molecular insights into emerging artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2011, 24 (6): 570–7. PMC 3268008 . PMID 22001944. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834cd3ed.

- ^ Fairhurst RM, Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Hallett R, Vennerstrom JL, Duong S, Ringwald P, Wellems TE, Plowe CV, Dondorp AM. Artemisinin-resistant malaria: research challenges, opportunities, and public health implications. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012, 87 (2): 231–41. PMC 3414557 . PMID 22855752. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0025.

- ^ Waters NC, Edstein MD. 8-Aminoquinolines: Primaquine and tafenoquine. Staines HM, Krishna S (eds) (编). Treatment and Prevention of Malaria: Antimalarial Drug Chemistry, Action and Use. Springer. 2012: 69–93 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-3-0346-0479-6. (原始内容存档于2016-06-17).

- ^ Rajapakse, Senaka; Rodrigo, Chaturaka; Fernando, Sumadhya Deepika. Tafenoquine for preventing relapse in people with Plasmodium vivax malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd). 2015-04-29, 4: CD010458 [2016-05-03]. PMC 4468925 . PMID 25921416. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010458.pub2. (原始内容存档于2017-01-26).

- ^ Lacerda, Marcus V.G.; Llanos-Cuentas, Alejandro; Krudsood, Srivicha; Lon, Chanthap; Saunders, David L.; Mohammed, Rezika; Yilma, Daniel; Batista Pereira, Dhelio; Espino, Fe E.J. Single-Dose Tafenoquine to Prevent Relapse of Plasmodium vivax Malaria. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019-01-17, 380 (3): 215–228. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 6657226 . PMID 30650322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710775.

- ^ Kochar, DK; Saxena, V; Singh, N; Kochar, SK; Kumar, SV; Das, A. Plasmodium vivax malaria.. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005-01, 11 (1): 132–4. PMC 3294370 . PMID 15705338. doi:10.3201/eid1101.040519.

- ^ Sinclair D, Donegan S, Isba R, Lalloo DG. Sinclair, David , 编. Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012, 6: CD005967. PMID 22696354. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005967.pub4.

- ^ Kyu, Hmwe Hmwe; Fernández, Eduardo. Artemisinin derivatives versus quinine for cerebral malaria in African children: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009, 87: 896–904 [2016-08-23]. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.060327. (原始内容存档于2016-03-04).

- ^ Sinha, Shweta; Medhi, Bikash; Sehgal, Rakesh. Challenges of drug-resistant malaria. Parasite. 2014, 21: 61. ISSN 1776-1042. PMID 25402734. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014059.

- ^ White NJ. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): The price of success. Science. 2008, 320 (5874): 330–4. PMID 18420924. doi:10.1126/science.1155165.

- ^ Wongsrichanalai C, Meshnick SR. Declining artesunate-mefloquine efficacy against falciparum malaria on the Cambodia–Thailand border. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008, 14 (5): 716–9 [2015-05-20]. PMC 2600243 . PMID 18439351. doi:10.3201/eid1405.071601. (原始内容存档于2010-03-09).

- ^ Dondorp AM, Yeung S, White L, Nguon C, Day NPJ, Socheat D, von Seidlein L. Artemisinin resistance: Current status and scenarios for containment. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2010, 8 (4): 272–80. PMID 20208550. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2331.

- ^ World Health Organization. Q&A on artemisinin resistance. WHO malaria publications. 2013. (原始内容存档于2016-07-20).

- ^ Ashley EA; Dhorda M; Fairhurst RM; Amaratunga C; Lim P; et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014, 371 (5): 411–23. PMID 25075834. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1314981.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): If I get malaria, will I have it for the rest of my life?. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010-02-08 [2012-05-14]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-13).

- ^ Trampuz A, Jereb M, Muzlovic I, Prabhu R. Clinical review: Severe malaria. Critical Care. 2003, 7 (4): 315–23. PMC 270697 . PMID 12930555. doi:10.1186/cc2183.

- ^ 149.0 149.1 149.2 149.3 Fernando SD, Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. The 'hidden' burden of malaria: Cognitive impairment following infection. Malaria Journal. 2010, 9: 366. PMC 3018393 . PMID 21171998. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-9-366.

- ^ Riley EM, Stewart VA. Immune mechanisms in malaria: New insights in vaccine development. Nature Medicine. 2013, 19 (2): 168–78. PMID 23389617. doi:10.1038/nm.3083.

- ^ 151.0 151.1 Idro R, Marsh K, John CC, Newton CRJ. Cerebral malaria: Mechanisms of brain injury and strategies for improved neuro-cognitive outcome. Pediatric Research. 2010, 68 (4): 267–74. PMC 3056312 . PMID 20606600. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181eee738.

- ^ Malaria. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010-04-15 [2012-05-02]. (原始内容存档于2012-04-16).

- ^ World Malaria Report 2012 (PDF) (报告). World Health Organization. [2015-05-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-12-22).

- ^ Olupot-Olupot P, Maitland, K. Management of severe malaria: Results from recent trials. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2013, 764: 241–50. ISBN 978-1-4614-4725-2. PMID 23654072. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4726-9_20.

- ^ 155.0 155.1 155.2 Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2012, 379 (9814): 413–31. PMID 22305225. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8.

- ^ Lozano R; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.

- ^ Achieving the malaria MDG target: reversing the incidence of malaria 2000-2015. (PDF). UNICEF. WHO. 2015-09 [2015-12-26]. ISBN 978924150944 2. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-01-05).

- ^ Bhatt, S.; J. Weiss, D.; Cameron, E.; Bisanzio, D.; Mappin, B.; Dalrymple, U.; Battle, K.E.; Moyes, C.L.; Henry, A.; Eckhoff, P.A.; Wenger, E.A.; Briët, O.; Penny, M.A.; Smith, T.A.; Bennett, A.; Yukich, J.; Eisele, T.P.; Griffin, J.T.; A. Fergus, C.; Lynch, M.; Lindgren, F.; Cohen, J.M.; Murray, C.L.J.; Smith, D.L.; Hay, S.I.; Cibulskis, R.E.; Gething, P.W. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015-09-16, 526 (7572): 207–211 [2016-07-31]. PMID 26375008. doi:10.1038/nature15535. (原始内容存档于2015-10-07).

- ^ Layne SP. Principles of Infectious Disease Epidemiology (PDF). EPI 220. UCLA Department of Epidemiology. [2007-06-15]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2006-02-20).

- ^ Provost C. World Malaria Day: Which countries are the hardest hit? Get the full data. The Guardian. 2011-04-25 [2012-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2012-04-14).

- ^ 161.0 161.1 Guerra CA, Hay SI, Lucioparedes LS, Gikandi PW, Tatem AJ, Noor AM, Snow RW. Assembling a global database of malaria parasite prevalence for the Malaria Atlas Project. Malaria Journal. 2007, 6 (1): 17. PMC 1805762 . PMID 17306022. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-6-17.

- ^ Hay SI, Okiro EA, Gething PW, Patil AP, Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Snow RW. Mueller, Ivo , 编. Estimating the global clinical burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 2007. PLoS Medicine. 2010, 7 (6): e1000290. PMC 2885984 . PMID 20563310. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000290.

- ^ Gething PW, Patil AP, Smith DL, Guerra CA, Elyazar IR, Johnston GL, Tatem AJ, Hay SI. A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malaria Journal. 2011, 10 (1): 378 [2015-05-20]. PMC 3274487 . PMID 22185615. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-378. (原始内容存档于2012-04-07).

- ^ Malaria in endemic areas: Epidemiology, prevention, and control. www.uptodate.com. [2016-11-25]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-26).

- ^ Greenwood B, Mutabingwa T. Malaria in 2002. Nature. 2002, 415 (6872): 670–2. PMID 11832954. doi:10.1038/415670a.

- ^ Jamieson A, Toovey S, Maurel M. Malaria: A Traveller's Guide. Struik. 2006: 30 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-1-77007-353-1. (原始内容存档于2016-05-11).

- ^ Abeku TA. Response to malaria epidemics in Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007, 14 (5): 681–6. PMC 2738452 . PMID 17553244. doi:10.3201/eid1305.061333.

- ^ Cui L, Yan G, Sattabongkot J, Cao Y, Chen B, Chen X, Fan Q, Fang Q, Jongwutiwes S, Parker D, Sirichaisinthop J, Kyaw MP, Su XZ, Yang H, Yang Z, Wang B, Xu J, Zheng B, Zhong D, Zhou G. Malaria in the Greater Mekong Subregion: Heterogeneity and complexity. Acta Tropica. 2012, 121 (3): 227–39. PMC 3132579 . PMID 21382335. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.02.016.

- ^ Machault V, Vignolles C, Borchi F, Vounatsou P, Pages F, Briolant S, Lacaux JP, Rogier C. The use of remotely sensed environmental data in the study of malaria. Geospatial Health. 2011, 5 (2): 151–68 [2015-07-05]. PMID 21590665. doi:10.4081/gh.2011.167. (原始内容存档于2016-03-05).

- ^ Humphreys M. Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States. Johns Hopkins University Press. 2001: 256. ISBN 0-8018-6637-5.

- ^ Sachs J, Malaney P. The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature. 2002, 415 (6872): 680–5. PMID 11832956. doi:10.1038/415680a.

- ^ Roll Back Malaria-Faire reculer le paludisme. Le paludisme en Afrique (PDF). [2020-09-15]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-09-29).

- ^ Ricci F. Social implications of malaria and their relationships with poverty. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2012, 4 (1): e2012048. PMC 3435125 . PMID 22973492. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2012.048.

- ^ Lon CT, Tsuyuoka R, Phanouvong S, Nivanna N, Socheat D, Sokhan C, Blum N, Christophel EM, Smine A. Counterfeit and substandard antimalarial drugs in Cambodia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006, 100 (11): 1019–24. PMID 16765399. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.01.003.

- ^ Newton PN, Fernández FM, Plançon A, Mildenhall DC, Green MD, Ziyong L, Christophel EM, Phanouvong S, Howells S, McIntosh E, Laurin P, Blum N, Hampton CY, Faure K, Nyadong L, Soong CW, Santoso B, Zhiguang W, Newton J, Palmer K. A collaborative epidemiological investigation into the criminal fake artesunate trade in South East Asia. PLoS Medicine. 2008, 5 (2): e32. PMC 2235893 . PMID 18271620. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050032.

- ^ Newton PN Green MD, Fernández FM, Day NPJ, White NJ. Counterfeit anti-infective drugs. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2006, 6 (9): 602–13. PMID 16931411. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70581-3.

- ^ Parry J. WHO combats counterfeit malaria drugs in Asia. British Medical Journal. 2005, 330 (7499): 1044. PMC 557259 . PMID 15879383. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7499.1044-d.

- ^ Gautam CS, Utreja A, Singal GL. Spurious and counterfeit drugs: A growing industry in the developing world. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2009, 85 (1003): 251–6. PMID 19520877. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2008.073213.

- ^ Caudron J-M, Ford N, Henkens M, Macé, Kidle-Monroe R, Pinel J. Substandard medicines in resource-poor settings: A problem that can no longer be ignored. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008, 13 (8): 1062–72. PMID 18631318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02106.x.

- ^ Nayyar GML, Breman JG, Newton PN, Herrington J. Poor-quality antimalarial drugs in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012, 12 (6): 488–96. PMID 22632187. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70064-6.

- ^ Russell PF. Communicable diseases. Malaria. Medical Department of the United States Army in World War II. U.S. Army Medical Department. Office of Medical History. 2009-01-06 [2012-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-09).

- ^ Melville CH. The prevention of malaria in war. Ross R (编). The Prevention of Malaria. New York, New York: E.P. Dutton. 1910: 577.

- ^ Bray RS. Armies of Pestilence: The Effects of Pandemics on History. James Clarke. 2004: 102 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-0-227-17240-7. (原始内容存档于2016-05-13).

- ^ Byrne JP. Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. 2008: 383 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1. (原始内容存档于2013-12-03).

- ^ History of Malaria During Wars. Malariasite.com. 2015-02-25 [2015-07-05]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-23).

- ^ History | CDC Malaria. Cdc.gov. 2010-02-08 [2012-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2010-08-28).

- ^ Stephanie Strom. Mission Accomplished, Nonprofits Go Out of Business. The New York Times. 2011-04-01. nytimes.com [2012-05-09]. OCLC 292231852. (原始内容存档于2011-12-25).

- ^ Impact and Results 2015 – Summary. The Global Fund. [2016-08-26]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-19).

- ^ Schoofs M. Clinton foundation sets up malaria-drug price plan. Wall Street Journal. 2008-07-17 [2012-05-14]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-23).

- ^ Executive summary and key points (PDF). World Malaria Report 2013. World Health Organization. [2014-02-13]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-04).

- ^ World Malaria Report 2013 (PDF). World Health Organization. [2014-02-13]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-04).

- ^ Meade MS, Emch M. Medical Geography 3rd. Guilford Press. 2010: 120–3 [2015-05-20]. ISBN 978-1-60623-016-9. (原始内容存档于2016-04-23).

- ^ Williams LL. Malaria eradication in the United States. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 1963, 53 (1): 17–21. PMC 1253858 . PMID 14000898. doi:10.2105/AJPH.53.1.17.

- ^ Breeveld FJV, Vreden SGS, Grobusch MP. History of malaria research and its contribution to the malaria control success in Suriname: A review. Malaria Journal. 2012, 11: 95. PMC 3337231 . PMID 22458802. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-95.

- ^ Yangzom T, Gueye CS, Namgay R, Galappaththy GN, Thimasarn K, Gosling R, Murugasampillay S, Dev V. Malaria control in Bhutan: Case study of a country embarking on elimination. Malaria Journal. 2012, 11: 9. PMC 3278342 . PMID 22230355. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-9.

- ^ Kow-Tong Chen, Chein-Jen Chen, Po-Ya Chang, Dale L. Morse. A Nosocomial Outbreak of Malaria Associated With Contaminated Catheters and Contrast Medium of a Computed Tomographic Scanner. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 1999-01, 20 (1): 22–25 [2018-04-02]. ISSN 0899-823X. doi:10.1086/501557. (原始内容存档于2018-06-18) (英语).

- ^ Stephen L. Hoffman, Peter F. Billingsley, Eric James, Adam Richman, Mark Loyevsky, Tao Li, Sumana Chakravarty, Anusha Gunasekera, Rana Chattopadhyay, Minglin Li, Richard Stafford, Adriana Ahumada, Judith E. Epstein, Martha Sedegah, Sharina Reyes, Thomas L. Richie, Kirsten E. Lyke, Robert Edelman, Matthew B. Laurens, Christopher V. Plowe, B. Kim Lee Sim. Development of a metabolically active, non-replicating sporozoite vaccine to prevent Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Human Vaccines. 2010-1, 6 (1): 97–106 [2019-02-12]. ISSN 1554-8619. PMID 19946222. (原始内容存档于2019-06-10).

- ^ Hill AVS. Vaccines against malaria. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2011, 366 (1579): 2806–14. PMC 3146776 . PMID 21893544. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0091.

- ^ Geels MJ, Imoukhuede EB, Imbault N, van Schooten H, McWade T, Troye-Blomberg M, Dobbelaer R, Craig AG, Leroy O. European Vaccine Initiative: Lessons from developing malaria vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2011, 10 (12): 1697–708. PMID 22085173. doi:10.1586/erv.11.158.

- ^ Crompton PD, Pierce SK, Miller LH. Advances and challenges in malaria vaccine development. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010, 120 (12): 4168–78. PMC 2994342 . PMID 21123952. doi:10.1172/JCI44423.

- ^ Graves P, Gelband H. Graves PM , 编. Vaccines for preventing malaria (blood-stage). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006, (4): CD006199. PMID 17054281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006199.

- ^ Graves P, Gelband H. Graves PM , 编. Vaccines for preventing malaria (SPf66). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006, (2): CD005966. PMID 16625647. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005966.

- ^ Davies L. WHO endorses use of world's first malaria vaccine in Africa. The Guardian. 2021-10-06 [2021-10-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-07).

- ^ Mandavilli A. A 'Historical Event': First Malaria Vaccine Approved by W.H.O.. New York Times. 2021-10-06 [2021-10-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-07).

- ^ Hoffman SL, Billingsley PF, James E, Richman A, Loyevsky M, Li T, Chakravarty S, Gunasekera A, Chattopadhyay R, Li M, Stafford R, Ahumada A, Epstein JE, Sedegah M, Reyes S, Richie TL, Lyke KE, Edelman R, Laurens MB, Plowe CV, Sim BK. Development of a metabolically active, non-replicating sporozoite vaccine to prevent Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Human Vaccines. 2010, 6 (1): 97–106. PMID 19946222. doi:10.4161/hv.6.1.10396.

- ^ Malaria Vaccine Advisory Committee. Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap (PDF) (报告). PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative (MVI): 2. 2006 [2016-08-25]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-08-26).

- ^ 世卫组织建议为高危儿童接种具有历史意义的“突破性”疟疾疫苗. [2021-10-07]. (原始内容存档于2021-12-22).

- ^ Kalanon M, McFadden GI. Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum and its apicoplast. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2010, 38 (3): 775–82. PMID 20491664. doi:10.1042/BST0380775.

- ^ Müller IB, Hyde JE, Wrenger C. Vitamin B metabolism in Plasmodium falciparum as a source of drug targets. Trends in Parasitology. 2010, 26 (1): 35–43. PMID 19939733. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2009.10.006.

- ^ Du Q, Wang H, Xie J. Thiamin (vitamin B1) biosynthesis and regulation: A rich source of antimicrobial drug targets?. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2011, 7 (1): 41–52. PMC 3020362 . PMID 21234302. doi:10.7150/ijbs.7.41.

- ^ Biot C, Castro W, Botté CY, Navarro M. The therapeutic potential of metal-based antimalarial agents: Implications for the mechanism of action. Dalton Transactions. 2012, 41 (21): 6335–49. PMID 22362072. doi:10.1039/C2DT12247B.

- ^ Roux C, Biot C. Ferrocene-based antimalarials. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2012, 4 (6): 783–97. PMID 22530641. doi:10.4155/fmc.12.26.

- ^ 213.0 213.1 Spillman, Natalie J.; Allen, Richard J.W.; McNamara, Case W.; Yeung, Bryan K.S.; Winzeler, Elizabeth A.; Diagana, Thierry T.; Kirk, Kiaran. Na+ Regulation in the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum Involves the Cation ATPase PfATP4 and Is a Target of the Spiroindolone Antimalarials. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013, 13 (2): 227–237. ISSN 1931-3128. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.12.006.

- ^ 214.0 214.1 Carroll, John. New malaria drug unleashes an immune system assault on infected cells. fiercebiotechresearch.com. 2014-12-08 [2015-06-27]. (原始内容存档于2016-04-04).

- ^ New Novartis drug cures malaria in mice. fiercebiotechresearch.com. 2010-09-07 [2015-06-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-29).

- ^ Aultman KS, Gottlieb M, Giovanni MY, Fauci AS. Anopheles gambiae genome: completing the malaria triad. Science. 2002, 298 (5591): 13. PMID 12364752. doi:10.1126/science.298.5591.13.

- ^ Ito J, Ghosh A, Moreira LA, Wimmer EA, Jacobs-Lorena M. Transgenic anopheline mosquitoes impaired in transmission of a malaria parasite. Nature. 2002, 417 (6887): 452–5. PMID 12024215. doi:10.1038/417452a.

- ^ Rich SM, Ayala FJ. Evolutionary origins of human malaria parasites. Dronamraju KR, Arese P (编). Malaria: Genetic and Evolutionary Aspects. New York, New York: Springer. 2006: 125–46. ISBN 978-0-387-28294-7.

- ^ Baird JK. Malaria zoonoses. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2009, 7 (5): 269–77. PMID 19747661. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.06.004.

- ^ Ameri M. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria in nonhuman primates. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2010, 39 (1): 5–19. PMID 20456124. doi:10.1111/j.1939-165X.2010.00217.x.

- ^ Mlambo G, Kumar N. Transgenic rodent Plasmodium berghei parasites as tools for assessment of functional immunogenicity and optimization of human malaria vaccines. Eukaryotic Cell. 2008, 7 (11): 1875–9. PMC 2583535 . PMID 18806208. doi:10.1128/EC.00242-08.

- ^ Lapointe DA, Atkinson CT, Samuel MD. Ecology and conservation biology of avian malaria. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012, 1249: 211–26. PMID 22320256. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06431.x.

外部链接

编辑- (繁体中文)中华民国疾病管制局-疟疾防治

- (简体中文)中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会-疟疾防治背景知识

- (英语)疟疾地图计划

- (英语)开放目录项目中的“疟疾”

- (英语)世卫组织的疟疾页面 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- (英语)全球疟疾行动计划(Global Malaria Action Plan) (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- (英语)无国界医生的疟疾页面 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- (英语)热带疾病研究培训特别计划-疟疾 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- (英语)疟疾预防

- (英语)疟疾药物预防 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- (英语)对抗疟疾与永续发展

- (英语)全球抗疟药物耐受性网络(WWARN) (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

延伸阅读

编辑- Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. Seuchen auf dem Vormarsch: Neue Strategien gegen verheerende Epidemien. Spektrum der Wissenschaft. 2015. ISBN 978-3-958-92016-3.(德语)

- Bynum WF, Overy C. The Beast in the Mosquito: The Correspondence of Ronald Ross and Patrick Manson. Wellcome Institute Series in The History of Medicine. Rodopi. 1998. ISBN 978-90-420-0721-5.

- Guidelines for the treatment of malaria 3. World Health Organization. 2015. ISBN 9789241549127.