结核病

结核病(tuberculosis,TB)是由结核分枝杆菌引起人畜共患的一种慢性传染病,其表现为器官内形成结核性肉芽肿(结核结节),继而结核中心干酪样坏死或钙化[4]。

| 结核病 | |

|---|---|

| 又称 | Phthisis, phthisis pulmonalis, consumption |

| |

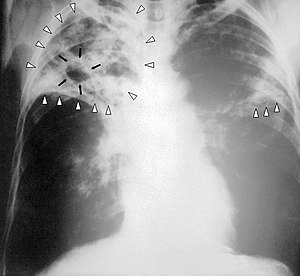

| 严重结核病患者的胸部X光:病灶位于白色箭头之中,其中包围的黑色部分为空腔。 | |

| 症状 | 慢性咳嗽、发烧、咳血、体重下降[1] |

| 类型 | 原发性细菌性传染病[*]、mycobacterium infectious disease[*]、地方性流行、传染病、疾病、新兴传染病 |

| 病因 | 结核杆菌 Mycobacterium tuberculosis[1] |

| 风险因素 | 吸烟、艾滋病[1] |

| 诊断方法 | 胸部X光、细菌培养、结核菌素试验[1] |

| 鉴别诊断 | 肺炎、组织胞浆菌病、结节病、粗球孢子菌症[2] |

| 治疗 | 抗细菌药[1] |

| 患病率 | 33%的人[1] |

| 死亡数 | 130万人(2016年)[3] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 感染科、胸腔医学、传染病 |

| ICD-10 | A15-A19 |

| OMIM | 607948 |

| DiseasesDB | 8515 |

| MedlinePlus | 000077、000624 |

| eMedicine | 230802 |

| Orphanet | 3389 |

结核通常造成肺部感染,也会感染身体的其他部分[1]。大多数感染者没有症状,此型态感染称为潜伏结核感染。10%的潜伏感染患者会恶化为活动性结核病[5](active tuberculosis),如果此时没有适当治疗,致死率为 50%。结核病的典型症状包含慢性咳嗽、咳血、发烧、夜间潮热,以及体重减轻[6]。感染其他器官则可能导致其他症状。[7]

结核病属于空气传播疾病。意即病原体会借由开放性肺结核[8](open tuberculosis)患者咳嗽、打喷嚏,或说话过程中所产生的飞沫散布[1][9];而潜伏性结核病患者则不会散布疾病。开放性结核常发生于鼠疫及艾滋病患者[1],需借由胸部X光、显微镜检,及体液培养来进行诊断。潜伏性结核病患者则可利用结核菌素试验或血液检查来诊断。[10]

预防肺结核可透过筛检高风险者、早期诊断和治疗,以及接种卡介苗等方法达成[11][12][13]。高风险者包含生活环境中与开放性结核病患者密切接触的人[13]。治疗通常搭配不同的抗生素组合做一段时间的治疗。近年带有抗生素抗药性的结核杆菌(MDR-TB)日益增加。[1]

世界上大约有三分之一的人口患有无法传染的潜伏性结核病[1]。全球每年大约有1%的人口新感染该病[14],2014年全球有960万名开放性结核病患者,150万例死亡,死亡者当中有95%是来自发展中国家。自2000年起,全球新病例数已逐年下降[1]。在许多亚洲与非洲国家,大约有80%的人肺结核检验结果为阳性,而在美国的人口中约有5-10%的人肺结核检验为阳性[15]。结核病在古代史中就有记载。[16]

临床体征与症状

编辑结核病可以在全身的任何一个部位发病,但最常发病于肺(即被称为肺结核、肺痨[19])。肺外结核病(即在肺以外的器官发生的结核病)可能与肺结核共同存在[7]。

结核病一般的临床体征与症状包括发热、发冷、盗汗、食欲不振、体重减轻以及疲倦[7]。结核病患者也可能出现明显的杵状指甲症状[20]。

肺结核

编辑开放性结核病最常见于肺部(占约90%的病例)[16][21]。肺结核的症状可能包含胸痛和长时间带痰咳嗽,而约有25%的人可能不会表现任何症状(即“无症状的”)[16]。 偶尔,患者可能小量的咳血、咳嗽,在极为罕见的病例中,感染可能侵蚀到肺动脉和雷斯莫森氏动脉瘤,导致大量出血[7][22]。肺结核可能演变成慢性疾病,并导致上肺叶产生大疤痕。上肺叶比下肺叶更易受到肺结核的影响[7],但这个差别的原因目前还未明。可能的解释为上肺叶的空气流通较佳[15],或其淋巴引流能力较差[7]。

肺外结核病

编辑在15%至20%的开放性结核病案例中,结核杆菌感染可传播至肺外,引起其他种类的结核病[23]。这些病症被归类为“肺外结核病”。 肺外结核病常发生于存在免疫抑制的个体或幼儿,50%以上患有肺结核的HIV病毒携带者均患有肺外结核病[24]。肺外结核病常发病于胸膜腔(结核性胸膜炎)、中枢神经系统(结核性脑膜炎)、淋巴系统(即颈部淋巴结核,又称瘰疬)、泌尿生殖道系统(即尿殖道结核),以及骨与筋腱(即博特氏病;脊柱结核性弯曲)等部位。当结核病发病于骨骼时,也被称为“骨结核病”[25],即一种骨髓炎[15]。有时结核性脓肿破出皮肤导致结核性溃疡[26]。由周围感染的淋巴结产生的溃疡常表现为无痛、缓慢扩大以及看起来像水洗过的皮革的特性[27]。弥散性结核病是一种更具危险性、更易扩散的结核病,也被称为粟粒状结核[7],粟粒状结核占肺外结核病例的10%[28]。

另外在台湾较常见的肺外结核为淋巴结核和骨结核,而结核性脑膜炎为其次,肺外结核的发生率比肺结核低[29]。而在中国大陆,以1996年至1999年上海市的流行病学研究为例,肺外结核发病案例以周围淋巴结结核为主,占38.3%,余依次为骨关节结核(19.9%)、泌尿生殖系统结核(16.7%)及肠、腹膜结核(9.1%)和脑神经结核(6.4%)。男女之比为1:1.35[30]。

病因

编辑分枝杆菌属

编辑结核杆菌是主要引起结核病的致病原,它是一个小型、好氧、不具活动性的细菌,属于分枝杆菌属[7]。结核杆菌的生长速度与其他细菌相比非常缓慢,细胞每16至20小时才分裂一次,而其他细菌一般则不到半小时即分裂一次[31]。结核杆菌还有一个特殊的双层脂质外膜[32]。细胞壁富含脂质是分枝杆菌属特有的临床特征[33],使用一般的革兰氏染色鉴定,会出现不明显的阳性反应或无法被染上色的现象,原因就是其细胞壁中富含脂质以及霉菌酸(分枝菌酸)(一种脂肪酸)[34]。在自然界,结核杆菌只能生长于宿主个体的细胞中,但在实验室中可在试管内培养[35]。

医检师可利用组织染色法处理痰液检体,便可用显微镜鉴别出结核杆菌。因为结核杆菌染色后不会被酸性溶剂冲洗掉,分类上又被称为抗酸性杆菌[15][34]。目前最常用的耐酸染色法是齐尔-尼尔森染色及金氏(Kinyoun)染色,两染色法在显微镜下所见的背景为蓝色,而结核杆菌则是呈现红色[36][37]。另外也可使用金胺-若丹明(Auramine-rhodamine )染色法,并在萤光显微镜下观察[38][39]。

结核分枝杆菌复合群(MTBC)包括其他四种可引起结核病的分枝杆菌属的细菌:牛分枝杆菌、非洲分枝杆菌、卡氏分枝杆菌及田鼠分枝杆菌[40]。 非洲分枝杆菌分布不广,但却是导致非洲结核病感染的重要因素[41][42]。牛分枝杆菌曾是导致结核病感染的常见因素,但因巴式消毒法在牛奶生产中的使用,在发达国家已几乎不再出现牛分枝杆菌导致结核病感染的病例[15][43]。卡式分枝杆菌较为罕见,且似乎仅出现于非洲之角(东北非洲),但也有少数几例病例出现于非洲裔移民中[44][45]。田鼠分枝杆菌也较为罕见,且几乎仅出现于免疫不全人群,但其盛行率可能被严重低估[46]

其他致病分枝杆菌属细菌包括痳疯杆菌、鸟分枝杆菌及堪塞斯分枝杆菌。后两者被归为非结核性分枝杆菌(NTM)。非结核性分枝杆菌既不能引起结核病也不能引起痳疯病,但其感染会导致相似于结核病的肺部疾病[47]。

危险因子

编辑有许多因子会让人更容易罹患肺结核。目前全球最重要的一项危险因子是HIV病毒;在罹患肺结核的病人中,有13%是HIV病毒感染的患者[48]。该问题在漠南非洲尤其显著,因为这个区域艾滋病罹患率相当高[49][50]。未感染HIV的肺结核患者中,有约5~10%日后发展为开放性肺结核;相比之下,同时感染HIV的肺结核患者日后有30%发展为开放性肺结核[20]。肺结核与拥挤环境、营养不良相关,这些特性使其成为贫穷病之一[16]。其他高风险因子则包含注射毒品、人口聚集场所居民及工作人员(如收容所及监狱)、医疗卫生较差区域、某些特定种族、与病患长期接触的孩童,以及医疗照护人员等等[51]。慢性肺部疾病是另一种重要的危险因子。矽肺症提高了大约30倍的风险[50]。吸烟者相于没有吸烟的族群,有大约两倍罹患肺结核的风险[52]。另外还有一些疾病也会提高肺结核的风险,包含酗酒、糖尿病(提高约3倍的患病几率)[53]。某些药物也逐渐成为重要的风险因子,尤其是在发达国家。例如皮质类固醇和英夫利西单抗(一种抗αTNF的单克隆抗体)。遗传易感性也是危险因子之一,然而其重要性目前仍未确立[16][54]。

发病机制

编辑传染途径

编辑肺结核不会经由无生命的东西传染,必须要直接或间接吸入飞沫才会得病[55]。当患有开放性肺结核的患者咳嗽、打喷嚏、说话、唱歌或吐痰,患者会释放出具有传染性、直径0.5至5.0µm(微米)的悬浮粒子。每个喷嚏可释放出高达40,000颗悬浮粒子[56]。由于肺结核的感染剂量非常低(吸入少于十个细菌即有可能造成感染),每一颗悬浮粒子都可能造成传染[57]。

结核菌必须包在飞沫(aerosol droplet)中才能达到感染的效果,当一个传染性肺结核病患在吐痰、咳嗽或打喷嚏时,含有结核菌的痰有机会变成细小的飞沫飘浮到空气中,飞沫的中心是结核菌,周围是痰,当痰逐渐蒸发,飞沫直径小到 5μm 以下时便可能直接进入正常人的肺泡,躲过宿主原有的呼吸道纤毛防卫机制(mucociliary system),直接与肺泡巨噬细胞接触。如吸入的结核菌数量不多、毒性不强;宿主巨噬细胞杀死结核菌能力相对足够的状况下,并不会导致感染。但如果一切状况不利于宿主,结核菌就有可能开始增殖[58]。与肺结核患者长期、频繁或亲密接触者皆有非常高的感染风险,感染率约为22%[59]。未经治疗的开放性肺结核患者每年会传染10至15人(或更多)[60]肺结核只由开放性患者传染给其他人(也就是说所有“活动性”患者也具感染性),而潜伏结核感染患者与非开放性肺结核患者一般并不被认为具有感染性[15]。多个因素同时影响个体之间的传染几率,其中包括病患喷出飞沫的悬浮粒子数量、通风情况、暴露于感染源的持续时间、结核分枝杆菌菌株的致病性,以及个体的免疫力等等[61]。人与人间的传染可以借由隔离具有传染性肺结核的患者和给予抗结核的药物治疗来避免。大约在两个星期有效的治疗后,没有抗生素抗药性之患者一般不会传染给其他者[59]。人被传染后通常需要3至4周的时间,才会具有足够传染力去传染别人[62]。

病因

编辑大约90%的结核杆菌感染者是无症状 、潜伏的(也被称为潜伏结核感染,LTBI)[63],结核病由结核感染期进展至临床结核病期的时间差变异大,短则数周,长可达一生,受感染宿主终生危险期(lifetime risk)为10%。进展时间呈指数分布,约70—80%的临床结核病在感染后5年内发生。停留于结核感染期者,无临床症状也不具感染性,称为潜伏性结核感染[64], 只有10%的感染者的一生中某个时段会发展成开放性结核病。而HIV感染者中有潜伏结核感染的发展为开放性结核病的几率可增加至每年10%[65]。若未经有效治疗,开放性结核病的死亡率可达66%[60]。

肺结核感染始于结核杆菌感染肺泡,结核杆菌可侵入肺泡并在其巨噬细胞的核内体中复制[15][66]。巨噬细胞辨认结核杆菌为异己并尝试以吞噬作用清除。在此过程中,结核杆菌被巨噬细胞包裹并暂时储存于吞噬体中,即一种膜连型囊泡。之后吞噬体与溶酶体结合,形成吞噬溶酶体。在吞噬溶酶体中细胞尝试使用活性氧类及酸来杀死细菌,但结核杆菌有一层蜡状的厚层霉菌酸构成的囊状结构,以此保护其自身免于毒性物质的侵害。因此结核杆菌可以在巨噬细胞里复制并最终杀死巨噬细胞。

临床结核病(clinical tuberculosis)中,一般感染后5年内发病者,为原发性结核病(primary tuberculosis),超过5年者为次发性结核病(secondary tuberculosis)[64]。原发性肺结核在肺部好发的部位称为“肺结核原发病灶(Ghon氏病灶)”,通常位于下叶的上半部或是上叶的下半部[15]。结核菌也可能透过血液循环而感染到肺部,通常会感染道肺部的顶部这被称作“Simon氏病灶”[67]。80%以上的结核菌会感染肺部形成肺结核[64],血液循环也可能把感染带到身体其他远端部位,例如周边淋巴结、肾脏、脑部和骨骼,造成肺外结核[15][68]。全身所有部位都有机会被结核菌感染,但是心脏、骨骼肌、胰脏以及甲状腺较少受到侵犯,其机制至今未明[69]。肺外结核患者不一定会咳嗽,最明显症状则是感染处肿胀、疼痛[64]。

结核病被归类为一种肉芽肿性炎症。巨噬细胞、T细胞、B细胞以及纤维母细胞 聚集为肉芽肿,且淋巴细胞会围绕受感染的巨噬细胞。其他巨噬细胞会在肺泡囊融合为一个多核的细胞以攻击受感染的巨噬细胞。肉芽肿的形成可以避免结核杆菌散播,也提供一个局部环境让免疫系统的细胞之间交互作用[71]。然而,最近的证据显示结核杆菌利用肉芽肿避免被宿主免疫系统破坏。巨噬细胞和树状细胞在肉芽肿中无法发挥对淋巴球呈现抗原 的功能,这即导致免疫反应被抑制[72]。肉芽肿中的细菌可能休眠,造成潜伏感染。肉芽肿的另一个特色是会造成结节中心的不正常的细胞坏死。在肉眼观察下,这样的病灶会呈现质地软类似白色乳酪的坏死,称为干酪性坏死[71]。

当结核菌从受感染的组织进入血流,它们可以在身体散布,并在组织中形成许多细小的白色节结[73]。这种严重的结核病称做粟粒状结核,最好发的族群是年幼孩童和人类免疫缺陷病毒患者[74]。罹患这种弥漫型的结核病,即使经过治疗也有很高的死亡率 (大约30%)[28][75]。

在大多数的患者中,感染病程起起伏伏。组织的破坏和坏死通常以愈合和纤维化作结。受侵犯的组织通常会被疤痕或填满干酪性坏死的空腔所取代。在开放性肺结核的时期,一些空腔与空气行经的支气管相连,内含的物质就会被咳出来,也包含了结核菌的活体,于是透过这种方式传播。适当的抗生素治疗可以杀死细菌,并让愈合得以进行。当痊愈时,受感染的区域最终会被疤痕组织取代[71]。

诊断

编辑诊断的方法可以依据临床表现与X光,也可以参考结核菌素试验、组织病理切片、耐酸性染色、结核菌培养、MTB PCR。

活动性结核病(开放性结核病)

编辑只依据临床表现和症状就要下活动性结核病的诊断并不容易[76],如同在免疫低下的个案诊断这类疾病。当肺部症状或全身症状持续超过两周时,结核病的诊断就应该被考虑。初步检查典型包含了胸部X光、多套针对抗酸菌的痰液培养[77]。丙型干扰素检验与结核菌素皮肤测试在发展中国家有一点角色[78][79]。丙型干扰素检验有些局限,如同它在人类免疫缺陷病毒的角色一般[79][80]。

要在检体(痰、脓或活体组织切片)上确认到结核菌,才算是确定诊断患有结核病。但血液或痰液的细菌培养需二周到六周[81],因此常会在确定有结核病前就开始治疗[82]。因细菌学检查后,检体内有结核菌,此时病人具传染性,为结核病防治的对象(称为传染性结核病或开放性结核病)。痰细菌学检查一般采用涂片抗酸菌染色及结核菌培养二种方式,痰涂片可侦测出痰中细菌量大的病人;至于痰中细菌量小的病患,即痰涂片阴性者,可借由痰培养发现细菌。研究显示,同样是培养阳性的病患,涂片阳性者的传染性是涂片阴性者二倍以上。[83]

核酸扩增试验及腺苷脱氨酶检测检验可以提供结核病快速诊断[76]。不过因为这些检验方式鲜少改变病人的治疗计划,所以不是例行性的建议检验项目[82]。检验血中的抗体因为灵敏度和特异度不出色,所以也不是建议的检验项目[84]。

潜伏性结核病(非开放性结核病)

编辑痰液中找不到结核菌时,亦可由胸部X光检查加上病人的临床症状,实验室检查之数据,作为肺结核的临床诊断依据(称非传染性结核病或非开放性结核病)。[83]结核菌素试验通常应用于筛检结核病的高危险群[77]。先前接受过疫苗的人可能会有伪阳性的检验结果[85]。罹患结节病、霍奇金淋巴瘤或是营养不良的人,以及最需要注意的活动性结核病患者,可能会有伪阴性的检验结果[15]。抽血做丙型干扰素检验(IGRAs)建议应用于结核菌素试验阳性的个案[82]。丙型干扰素检验不会因为先前接种过疫苗或是大部分非结核性分枝杆菌而产生伪阳性[86]。然而可能会受到M. szulgai、M. marinum 以及 M. kansasii干扰[87]。丙型干扰素检验合并皮肤测试可以提高敏感度,然而单独使用丙型干扰素检验的敏感度确比皮肤试验还要低[88]。

预防

编辑肺结核的预防与控制须从婴儿时期的疫苗施打,以及对活动性结核病患者的检测及适当治疗着手。世界卫生组织已借着改善治疗方法达到些许成效,并使感染人数有小幅度的下降[16]。美国预防服务任务小组(USPSTF)建议对于可能罹患潜伏性结核病的高风险族群进行结核菌素试验,或是全血丙型干扰素检验(interferon-gamma release assays)[89]。

疫苗

编辑1920-21年,法国疫苗学家阿尔伯特·卡尔梅特和卡米尔·介兰研发出对抗结核病的卡介苗(BCG)[90]。截至2011年,对抗结核病的疫苗仍只有卡介苗一种[91]。已接种卡介苗的孩童可降低20%的感染风险,感染后发病的风险也可降低近60%[92]。

卡介苗是全世界被运用的最广泛的疫苗,儿童接种率超过九成。卡介苗的免疫作用在大约10年后会逐渐下降[16]。结核病在加拿大、英国及美国不太普遍,因此卡介苗只会被使用在肺结核高风险的群众上[93][94][95]。反对使用卡介苗的部分因素是因为它会造成结核菌素试验产生伪阳性的结果,减少此试验的使用[95]。目前有许多新的肺结核疫苗正在研发当中[16]。2018年,M72/AS01E的第二期试验显示可以显著降低开放性结核发生的风险[96]。

公共卫生

编辑世界卫生组织在1993年时宣布肺结核疫情进入“全球紧急状态”(global health emergency)[16],在2006年终止结核伙伴联盟发起了全球结核病防治计划,希望能在2006年到2015年之间救治1400万条生命[97]。然而,随着HIV关联的结核病患者增加,以及多重抗药性菌株的影响,使这个目标在2015年时并未达成[16]。美国胸腔协会制定的结核病分级标准已被广泛运用在公共卫生计划当中[98]。

治疗

编辑结核病的治疗通常使用抗生素,但由于结核分枝杆菌细胞壁成分和构造较为特殊,药物较难进入病原体中,因此难以发挥药效[99]。目前最常用的抗生素为异烟肼(Isoniazid)及利福平(Rifampin),且通常需服药长达数月[61]。潜伏性结核病通常可给予单一抗生素治疗,而活动性肺结核则最好同时合并使用多种抗生素治疗,以减少结核菌产生抗药性的风险。除活动性结核病患者外,潜伏性结核病患者也建议进行治疗,以避免在未来恶化为活动性结核病[100]。结核病的治疗需要长期不间断的服药,自行中断服药或忘记服药容易导致治疗失败。因此世界卫生组织建议实施“都治计划”(DOTs),即由医疗照护人员亲自定期送药,监督患者确实服药[101]。中华民国卫生福利部的资料显示,实施都治计划能有效降低治疗失落率,与对照组比较起来也能明显提升治疗成功率[102]。都治计划的实施手段似乎对于治疗成果有显著影响[103]。然而在治愈率方面,计划实施组与自主服药组并没有太大差异[104]。

首次发病

编辑截至2010年,肺结核首次发病的建议疗法是六个月的抗生素综合治疗,首两个月使用利福平、异烟肼(Isoniazid)、吡嗪酰胺(Pyrazinamide)及乙胺丁醇(Ethambutol);最后四个月只使用利福平和异烟肼。如果对异烟肼的抗药性高,后四个月疗程可用乙胺丁醇取代之[16]。

复发

编辑如果肺结核复发,在选择治疗方法前测试细菌对哪些抗生素有敏感性很重要。如果检验出细菌对多种药物有抗药性(MDR-TB),建议使用最少四种有效的抗生素进行18到24个月的疗程[16]。

抗药性

编辑原发性抗药性肺结核发生在受具抗药性结核杆菌感染的人中。带有易受触动的结核分枝杆菌的人可能在治疗过程中因治疗不足、没有正确按医嘱服药或药物品质低劣而得到多发性肺结核[105]。抗药性肺结核在很多发展中国家是一个严重的公共卫生议题,因为这延长疗程及需要较昂贵药物。

多重抗药性结核病(MDR-TB)的定义是结核菌同时对两种最有效的第一线药物利福平和异烟肼具抗药性。广泛耐药结核则是指同时对三种以上或六类第二线药物具抗药性[106]。完全抗药性结核病是指对所有用作治疗的药物具抗药性[107]。此类结核病于2003年在意大利首次发现[108],在伊朗和印度也有案例[109][110],不过到2012年才有广泛报告[107][111]。贝达喹啉(Bedaquiline)暂时受到认受作为治疗多重抗药性结核病的药物[112]。高剂量莫西沙星配合其他抗结核病药物也被证实可以缩短病程[113]。

在每十宗多重抗药性结核病里,就有一例是广泛耐药结核病。逾九成国家有广泛耐药结核病的病例[109]。

预后

编辑| no data ≤10 10–25 25–50 50–75 75–100 100–250 | 250–500 500–750 750–1000 1000–2000 2000–3000 ≥ 3000 |

当细菌突破免疫系统的防御而开始增生时,疾病会由结核菌感染进展到症状明显的结核病。在原发型结核病 (占 1-5% 的比例),这种现象会在感染刚开始的时候很快的发生。然而多数人感染模式为潜伏结核感染,通常没有明显症状[15]。在5-10%潜伏结合感染的案例中,这些休眠的细菌经常会在感染后数年的时间制造出活动的结核[20]。

疾病再活化的几率会随着免疫抑制增加,例如因为感染了人类免疫缺陷病毒。同时感染有结核菌和人类免疫缺陷病毒的患者,结核再活化得几率会上升到每年10%之多[15]。利用遗传指纹分析鉴定结核菌的菌株的研究指出,“再度感染”在结核病复发的角色比先前的认知更重要[115],估计在结核病盛行区域占了疾病再活化的个案中的50%[116]。结核病的致死率在2008年大约为4%,相较于1995年的8%已有下降[16]。

耐药变种

编辑由于病人漏服治疗药物,或在治疗周期完成前终止治疗而产生的结核病耐药变种对治疗药物有不同程度的抗药性。对利福平(rifampicin)和异烟肼(isoniazid)等一线药物具抗药性的结核称作“多药抗药性结核”(MDR-TB)。多药抗药性结核中,对全部喹诺酮类药物以及至少对二线治疗结核药物中卡那霉素(kanamycin)、卷曲霉素(capreomycin)和阿米卡霉素之一具有抗药性的结核病称为广泛耐药结核(XDR-TB)。

耐药结核具有死亡率高(MDR-TB死亡率与肺癌类似,XDR-TB更高出很多),传染性低的特点,通常只由普通结核病人治疗不当产生,只有在低免疫人群(如HIV普遍感染)中会出现人与人直接传播。

历史

编辑工业革命前

编辑结核病是古老的疾病,至少可溯至新石器时代,在世界各地的历史上都不乏有死于肺结核的名人,比如中国近代著名作家鲁迅、发明听诊器的法国医师勒内·拉埃内克、演出电影《乱世佳人》的英国演员费雯丽、日本作家石川啄木及现代俳句之父“俳圣”正冈子规,幕末时期新撰组的天才剑士,三段突刺的最后传人冲田总司,以及台湾早期小说家锺理和,和发明数学公式,并对未来科学家研究黑洞有帮助的数学家斯里尼瓦瑟·拉马努金等等。历代名医对结核病都有深刻的认识。明代的李梃《医学入门》指出肺痨六大主症为:“潮、汗、咳嗽,或见血,或遗精”。清朝人李用粹《证治汇补》对结核病的描述:“痨瘵外候,睡中盗汗,午后发热,烦躁咳嗽,倦怠无力,饮食少进,痰涎带血,咯唾吐衄,肌肉消瘦”。

工业革命及其后

编辑18世纪、19世纪,结核病在欧洲成为流行病,其爆发呈现出季节性规律[118][119]。工业革命期间,欧洲各国开始出现严重环境污染,工人生产、居住和公共卫生条件简陋,与结核病的流行紧密相关[119][120]。18世纪,西欧结核病的死亡率高达900人/每十万人口,北美地区也有相似死亡率[118][121][122] 。英国的流行性结核病在1750年左右达到高峰[119]。 19世纪,结核病大约杀死了四分之一的欧洲成年人口[123]。在欧洲大陆西部,流行性结核病大概在19世纪上半叶到达高峰[124]。 此外,1851年至1910年间,英格兰和威尔士约有400万人死于结核病,超过1/3的15岁至34岁人口、一半的20岁至24岁人口死亡[125]。 到了19世纪末,欧洲和北美地区约70–90%的城市人口携带结核杆菌,而发病的人口中约80%死亡。但从同时间起,结核病在欧洲和美国的死亡率开始逐渐下降[126]。

在结核病流行期间,人们曾称它为“年轻人的强盗(the robber of youth)”,因为青年人患病率和死亡率较高[122][125]。其它的名字包括“白瘟疫(the Great White Plague)”以及“白死病(the White Death)”,因为患病者往往因贫血而脸色苍白[122][125][127]。此外,结核病也被许多人称为“所有这些死人的队长(Captain of All These Men of Death)”[122][125][127][128]。

1882年,德国医师罗伯特·科赫(Robert Koch)首次发现结核杆菌,他也因结核病的研究获得1905年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[129]。1921年,阿尔贝·卡尔梅特与卡米尔·介兰发明了卡介苗(BCG),用来预防肺结核,该疫苗已成为世界上最广泛接种的疫苗之一[90][130]。1944年链霉素(Streptomycin)发明[131],是为第一个有效的抗结核药物。虽然新的抗结核药物陆续被发展出来,然而结核病仍然是棘手的公共卫生问题。

治疗计划

编辑台湾都治计划

编辑消除结核第一期计划从2016年至2035年发生率由每10万人口46例降至10例。[132]结核病治疗期程较长及药物抗药性等问题,直接观察治疗(Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course, DOTS;音译为“都治”)是近年来世界卫生组织之策略。[58]DOTS计划相当重要的目标是预防多重抗药性细菌之产生,因此进一步针对多重抗药性结核高盛行地区推出加强型都治计划(DOTS-plus),以防止抗药性结核问题继续恶化[133]。

结核病的DOTS包括五大要项的配套策略:政府对结核防治之政治承诺、正确的个案诊断模式、标准化之治疗处方、充足的药物供应、标准化之登记与通报系统。[58]

中华民国卫生福利部为提升结核病照护成效下,进行的护理人员监督计划,执行阶段:[134][135]

执行方式:[58]

- 关怀员送药到点:由都治关怀员一事先约定好之服药地点及时间,亲自送药到指定地点,亲眼目睹病人服药。

- 个案到点服药:依病人服药意愿,病人自行至都治站,于关怀员或个案管理人员目视下服药。

配套计划:

为避免结核抗药性继续蔓延至无法控制,疾病管制局的都治计划(如上述)以验痰结果为主要指标。至于针对病患服药的顺从度不佳,健保局则推出“肺结核医疗给付改善试办计划”[133],鼓励医事机构提供结核病患整体性照护与个案管理的照护模式,为一套采取论质计酬的试办计划[136]。

社会和文化

编辑世界卫生组织、比尔与美琳达·盖茨基金会及美国政府在中低收入的国家进行一项计划,用补贴的方式协助进行一项全新的速效诊断测试[137][138][139]。可以将成本由美金16.86元降至美金9.98元。此测试还可以确认结核病对利福平是否有抗药性,若有,就有可能是多药抗药性结核,而且对于也有受艾滋病毒传染的人也可以正确的检测[137][140]。不过在2011年时,有许多研究资源不足的国家仍只能用显微镜检测痰液的方式来检测[141]。

在2010年时印度的结核病患者最多,原因可能包括私人及公立医疗院所中的疾病控管能力不足[142]。像修订后的国家结核病控制计划(RNTCP)等计划,有助于减少病人在进入医疗院所后得到结核的程度及比例[143][144]。

由于监狱中恶劣而封闭的环境以及医疗卫生服务的缺乏,结核病在监狱中的发病率可达外界的100倍[145]。针对监狱中的结核病患者,红十字国际委员会与世界卫生组织、当地政府以及医疗机构合作,通过提供资金和设备以及对监狱内外的医务人员进行培训,帮助被拘禁的患者获得及时治疗。在阿塞拜疆,红十字国际委员会与当地政府合作的治疗耐多药结核的试点项目使200多名患者获得治疗。[146]而在吉尔吉斯斯坦两个监狱的治疗中,成功率已接近50%。[147]

世界纪念日

编辑联合国、世界卫生组织(WHO)定于每年的3月24日为世界防治结核病日,以纪念1882年德国微生物学家罗伯特·科霍向一群德国柏林医生发表他对结核病病原菌的发现。

参考文献

编辑- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104. WHO. October 2015 [2016-02-11]. (原始内容存档于2012-08-23).

- ^ Ferri, Fred F. Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders 2nd. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. 2010: Chapter T. ISBN 0323076998.

- ^ Global tuberculosis report. World Health Organization. [2017-11-09]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-30) (英国英语).

- ^ Rubin, Raphael; Strayer, David S.; Rubin, Emanuel; McDonald (M.D.), Jay M. Rubin's Pathology: Clinicopathologic Foundations of Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. ISBN 978-0-7817-9516-6.

- ^ 唐锦华,姜申,黄嫄,等. QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus鉴别活动性结核病与潜伏性结核感染的潜在价值探讨[J]. 中华检验医学杂志,2020,43(09):907-911. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn114452-20191126-00692

- ^ The Chambers Dictionary.. New Delhi: Allied Chambers India Ltd. 1998: 352 [2016-09-05]. ISBN 978-81-86062-25-8. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Dolin, [edited by] Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases 7th. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2010: Chapter 250. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

- ^ Isaacs D, Jones CA, Dalton D, Cripps T, Vidler L, Rochefort M, Bide E, Banner P, Crawford H. Exposure to open tuberculosis on a neonatal unit. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006 Sep;42(9):557-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00923.x. PMID 16925546.

- ^ Basic TB Facts. CDC. 2012-03-13 [2016-02-11]. (原始内容存档于2016-02-06).

- ^ Konstantinos, Anastasios. Diagnostic tests: Testing for tuberculosis. Australian Prescriber. 2010-02-01, 33 (1): 12–18. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2010.005.

- ^ Hawn, Thomas R.; Day, Tracey A.; Scriba, Thomas J.; Hatherill, Mark; Hanekom, Willem A.; Evans, Thomas G.; Churchyard, Gavin J.; Kublin, James G.; Bekker, Linda-Gail. Tuberculosis Vaccines and Prevention of Infection. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2014-12, 78 (4): 650–671 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 1092-2172. PMC 4248657 . PMID 25428938. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00021-14. (原始内容存档于2022-07-09) (英语).

- ^ Harris, Randall E. Epidemiology of chronic disease: global perspectives. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2013: 682. ISBN 9780763780470.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Organization, World Health. Implementing the WHO Stop TB Strategy: a handbook for national TB control programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008: 179 [2016-09-05]. ISBN 9789241546676. (原始内容存档于2016-02-16).

- ^ Tuberculosis. World Health Organization. 2002. (原始内容存档于2013-06-17).

- ^ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN. Robbins Basic Pathology 8th. Saunders Elsevier. 2007: 516–522. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 Lawn, Stephen D.; Zumla, Alimuddin I. Tuberculosis. The Lancet. 2011-07-02, 378 (9785) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 21420161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3. (原始内容存档于2011-10-17) (英语).

- ^ Xiao, Zhishu; Zhang, Libiao; Xu, Lei; Zhou, Qihai; Meng, Xiuxiang; Yan, Chuan; Chang, Gang. Problems and countermeasures in the surveillance and research of wildlife epidemics based on mammals in China. Biodiversity Science. 2020-05-20, 28 (5): 566 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 1005-0094. doi:10.17520/biods.2020124. (原始内容存档于2022-06-25) (英语).

- ^ Schiffman G. Tuberculosis Symptoms. eMedicineHealth. 2009-01-15 [2016-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2009-05-16).

- ^ 【肺癆】肺結核5大症狀 4個常用檢測方法查找潛伏結核桿菌 抗生素療程可根治. 明报健康网. (原始内容存档于2023-11-21).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Gibson, Peter G. (ed.); Abramson, Michael (ed.); Wood-Baker, Richard (ed.); Volmink, Jimmy (ed.); Hensley, Michael (ed.); Costabel, Ulrich (ed.). Evidence-Based Respiratory Medicine 1st. BMJ Books. 2005: 321 [2016-11-26]. ISBN 978-0-7279-1605-1. (原始内容存档于2015-12-08).

- ^ Behera, D. Textbook of Pulmonary Medicine 2nd. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2010: 457 [2016-11-21]. ISBN 978-81-8448-749-7. (原始内容存档于2016-08-10).

- ^ Halezeroğlu, S; Okur, E. Thoracic surgery for haemoptysis in the context of tuberculosis: what is the best management approach?. Journal of Thoracic Disease. March 2014, 6 (3): 182–5. PMID 24624281. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.25.

- ^ Jindal, editor-in-chief SK. Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2011: 549 [2016-11-21]. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Golden, Marjorie P.; Vikram, Holenarasipur R. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview. American Family Physician. 2005-11-01, 72 (9): 1761–1768 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 16300038. (原始内容存档于2022-07-12).

- ^ Kabra, [edited by] Vimlesh Seth, S.K. Essentials of tuberculosis in children 3rd. New Delhi: Jaypee Bros. Medical Publishers. 2006: 249 [2016-11-21]. ISBN 978-81-8061-709-6. (原始内容存档于2016-08-10).

- ^ Manual of Surgery. Kaplan Publishing. 2008: 75. ISBN 9781427797995.

- ^ Burkitt, H. George. Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis & Management 4th ed. 2007: 34. ISBN 9780443103452.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Ghosh, editors-in-chief, Thomas M. Habermann, Amit K. Mayo Clinic internal medicine: concise textbook. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2008: 789 [2016-12-09]. ISBN 978-1-4200-6749-1. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ 台灣衛生福利部疾病管制署-傳染病介紹-肺結核. [2016年9月12日]. (原始内容存档于2016年11月21日).

- ^ 黄建生; 沈梅; 孙亚玲; 李永祥; 夏珍. 上海市肺外结核的流行病学分析. 中华结核和呼吸杂志. 2000, (10): 28–30. ISSN 1001-0939. CNKI ZHJH200010011. CQVIP 4579683.

- ^ Jindal, editor-in-chief SK. Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2011: 525 [2016-11-26]. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H. Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins. Trends in Microbiology. March 2010, 18 (3): 109–16. PMC 2931330 . PMID 20060722. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005.

- ^ Southwick F. Chapter 4: Pulmonary Infections. Infectious Diseases: A Clinical Short Course, 2nd ed.. McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. 2007-12-10: 104, 313–4. ISBN 0-07-147722-5.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Madison B. Application of stains in clinical microbiology. Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 2001, 76 (3): 119–25. PMID 11475314. doi:10.1080/714028138.

- ^ Parish T.; Stoker N. Mycobacteria: bugs and bugbears (two steps forward and one step back). Molecular Biotechnology. 1999, 13 (3): 191–200. PMID 10934532. doi:10.1385/MB:13:3:191.

- ^ Medical Laboratory Science: Theory and Practice. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. 2000: 473 [2016-11-26]. ISBN 0-07-463223-X. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Acid-Fast Stain Protocols. 2013-08-21 [2016-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2011年10月1日).

- ^ Kommareddi S.; Abramowsky C.; Swinehart G.; Hrabak L. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: comparison of the fluorescent auramine-O and Ziehl-Neelsen techniques in tissue diagnosis. Human Pathology. 1984, 15 (11): 1085–1089. PMID 6208117. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80253-1.

- ^ van Lettow, Monique; Whalen, Christopher. Nutrition and health in developing countries 2nd. Totowa, N.J. (Richard D. Semba and Martin W. Bloem, eds.): Humana Press. 2008: 291 [2016-11-26]. ISBN 978-1-934115-24-4. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ van Soolingen D., et al. A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an exceptional isolate from Africa. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1997, 47 (4): 1236–45. PMID 9336935. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-4-1236.

- ^ Niemann, S.; Rüsch-Gerdes, S.; Joloba, M. L.; Whalen, C. C.; Guwatudde, D.; Ellner, J. J.; Eisenach, K.; Fumokong, N.; Johnson, J. L. Mycobacterium africanum Subtype II Is Associated with Two Distinct Genotypes and Is a Major Cause of Human Tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002-09, 40 (9): 3398–3405 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 130701 . PMID 12202584. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.9.3398-3405.2002. (原始内容存档于2022-03-26) (英语).

- ^ Niobe-Eyangoh, Sara Ngo; Kuaban, Christopher; Sorlin, Philippe; Cunin, Patrick; Thonnon, Jocelyn; Sola, Christophe; Rastogi, Nalin; Vincent, Veronique; Gutierrez, M. Cristina. Genetic Biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex Strains from Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Cameroon. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003-06, 41 (6): 2547–2553 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 156567 . PMID 12791879. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.6.2547-2553.2003. (原始内容存档于2022-03-26) (英语).

- ^ Thoen C, Lobue P, de Kantor I. The importance of Mycobacterium bovis as a zoonosis. Veterinary Microbiology. 2006, 112 (2–4): 339–45. PMID 16387455. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.047.

- ^ Acton, Q. Ashton. Mycobacterium Infections: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional. ScholarlyEditions. 2011: 1968 [2016-11-26]. ISBN 978-1-4649-0122-5. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Pfyffer, G. E.; Auckenthaler, R.; van Embden, J. D.; van Soolingen, D. Mycobacterium canettii, the smooth variant of M. tuberculosis, isolated from a Swiss patient exposed in Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1998-10, 4 (4): 631–634 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2640258 . PMID 9866740. doi:10.3201/eid0404.980414. (原始内容存档于2022-07-12).

- ^ Panteix, G; Gutierrez, MC; Boschiroli, ML; Rouviere, M; Plaidy, A; Pressac, D; Porcheret, H; Chyderiotis, G; Ponsada, M; Van Oortegem, K; Salloum, S; Cabuzel, S; Bañuls, AL; Van de Perre, P; Godreuil, S. Pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium microti: a study of six recent cases in France. Journal of Medical Microbiology. August 2010, 59 (Pt 8): 984–9. PMID 20488936. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.019372-0.

- ^ American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997, 156 (2 Pt 2): S1–25. PMID 9279284. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement.

- ^ World Health Organization. The sixteenth global report on tuberculosis (PDF). 2011. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-09-06).

- ^ World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control–surveillance, planning, financing WHO Report 2006. [2006-10-13]. (原始内容存档于2006-12-12).

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Chaisson, RE; Martinson, NA. Tuberculosis in Africa—combating an HIV-driven crisis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008-03-13, 358 (11): 1089–92. PMID 18337598. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0800809.

- ^ Griffith D, Kerr C. Tuberculosis: disease of the past, disease of the present. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing. 1996, 11 (4): 240–5. PMID 8964016. doi:10.1016/S1089-9472(96)80023-2.

- ^ van Zyl Smit, RN; Pai, M; Yew, WW; Leung, CC; Zumla, A; Bateman, ED; Dheda, K. Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD. European Respiratory Journal. January 2010, 35 (1): 27–33. PMID 20044459. doi:10.1183/09031936.00072909.

These analyses indicate that smokers are almost twice as likely to be infected with TB and to progress to active disease (RR of about 1.5 for latent TB infection (LTBI) and RR of ∼2.0 for TB disease). Smokers are also twice as likely to die from TB (RR of about 2.0 for TB mortality), but data are difficult to interpret because of heterogeneity in the results across studies.

- ^ Restrepo, Blanca I. Convergence of the tuberculosis and diabetes epidemics: renewal of old acquaintances. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007-08-15, 45 (4): 436–438 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 1537-6591. PMC 2900315 . PMID 17638190. doi:10.1086/519939. (原始内容存档于2022-07-12).

- ^ Möller, M; Hoal, EG. Current findings, challenges and novel approaches in human genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. March 2010, 90 (2): 71–83. PMID 20206579. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2010.02.002.

- ^ 衛生福利部 彰化醫院 MDR-TB. [2016-04-15]. (原始内容存档于2020-08-13).

- ^ Cole, Eugene C.; Cook, Carl E. Characterization of infectious aerosols in health care facilities: An aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies. American Journal of Infection Control. 1998-08-01, 26 (4). ISSN 0196-6553. PMC 7132666 . PMID 9721404. doi:10.1016/S0196-6553(98)70046-X (英语).

- ^ Nicas, Mark; Nazaroff, William W.; Hubbard, Alan. Toward Understanding the Risk of Secondary Airborne Infection: Emission of Respirable Pathogens. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 2005-03, 2 (3) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 1545-9624. PMC 7196697 . PMID 15764538. doi:10.1080/15459620590918466. (原始内容存档于2022-11-03) (英语).

- ^ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 台湾卫生福利部疾病管制署. 結核病防治工作手冊-第二版( 2016-03-23). 台湾卫生福利部疾病管制署. 2016-03-23 [2016-05-01]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-11).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 Ahmed N, Hasnain S. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in India: Moving forward with a systems biology approach. Tuberculosis. 2011, 91 (5): 407–3. PMID 21514230. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.006.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104. World Health Organization. November 2010 [2011-07-26]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-30).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis: What the Clinician Should Know (PDF) 5th. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination: 24. 2011 [2017-01-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-05-19).

- ^ Causes of Tuberculosis. Mayo Clinic. 2006-12-21 [2007-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-18).

- ^ Skolnik, Richard. Global health 101 2nd. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2011: 253 [2017-01-27]. ISBN 978-0-7637-9751-5. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 吴俊忠、吴雪霞、周以正、周如文、胡文熙、洪贵香、孙培伦等十七人. 临床微生物学:细菌与霉菌学 第七版.台北市: 五南图书出版股份有限公司.2019年10月: 134. ISBN 978-957-763-609-6

- ^ III, Arch G. Mainous; Pomeroy, Claire. Management of Antimicrobials in Infectious Diseases: Impact of Antibiotic Resistance. Springer Science & Business Media. 2010-02-04: 74 [2017-01-27]. ISBN 978-1-60327-239-1. (原始内容存档于2022-10-14) (英语).

- ^ Houben, Edith NG; Nguyen, Liem; Pieters, Jean. Interaction of pathogenic mycobacteria with the host immune system. Current Opinion in Microbiology. Host--microbe interactions: bacteria / edited by Chihiro Sasakawa and Jörg Hacker. 2006-02-01, 9 (1) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 1369-5274. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.014. (原始内容存档于2018-09-28) (英语).

- ^ Khan. Essence Of Paediatrics. Elsevier India. 2011: 401 [2017-01-27]. ISBN 978-81-312-2804-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Herrmann, Jean-Louis; Lagrange, Philippe-Henri. Dendritic cells and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: which is the Trojan horse?. Pathologie Biologie. 2005-01-01, 53 (1) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 0369-8114. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2004.01.004. (原始内容存档于2018-09-28) (英语).

- ^ Agarwal, Ritesh; Malhotra, Puneet; Awasthi, Anshu; Kakkar, Nandita; Gupta, Dheeraj. Tuberculous dilated cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized entity?. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2005-12, 5 (1) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 1090580 . PMID 15857515. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-5-29. (原始内容存档于2022-11-28) (英语).

- ^ Good, John Mason; Cooper, Samuel. The Study of Medicine. Harper. 1835: 32 (英语).

- ^ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Grosset, Jacques. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Extracellular Compartment: an Underestimated Adversary. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2003-03, 47 (3) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 149338 . PMID 12604509. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.3.833-836.2003. (原始内容存档于2022-10-27) (英语).

- ^ Bozzano, Federica; Marras, Francesco; Maria, Andrea De. IMMUNOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2014-04-07, 6 (1) [2022-03-26]. ISSN 2035-3006. PMC 4010607 . PMID 24804000. doi:10.4084/mjhid.2014.027. (原始内容存档于2022-06-08) (英语).

- ^ Crowley, Leonard V. An introduction to human disease: pathology and pathophysiology correlations 8th. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett. 2010: 374 [2017-01-27]. ISBN 978-0-7637-6591-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Anthony, Harries. TB/HIV a Clinical Manual. 2nd. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2005: 75 [2017-01-27]. ISBN 978-92-4-154634-8. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Jacob, Jesse T.; Mehta, Aneesh K.; Leonard, Michael K. Acute Forms of Tuberculosis in Adults. The American Journal of Medicine. 2009-01-01, 122 (1). ISSN 0002-9343. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.018 (英语).

- ^ 76.0 76.1 Bento, João; Silva, Anabela Santos; Rodrigues, Filomena; Duarte, Raquel. Diagnostic tools in tuberculosis. Acta Medica Portuguesa. 2011-01, 24 (1) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 1646-0758. PMID 21672452. (原始内容存档于2022-11-06).

- ^ 77.0 77.1 Escalante, P. In the clinic. Tuberculosis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009-06-02, 150 (11): ITC61–614; quiz ITV616. PMID 19487708. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-01006.

- ^ Metcalfe, JZ; Everett, CK; Steingart, KR; Cattamanchi, A; Huang, L; Hopewell, PC; Pai, M. Interferon-γ release assays for active pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in adults in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011-11-15,. 204 Suppl 4 (suppl_4): S1120–9. PMC 3192542 . PMID 21996694. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir410.

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Sester, M.; Sotgiu, G.; Lange, C.; Giehl, C.; Girardi, E.; Migliori, G. B.; Bossink, A.; Dheda, K.; Diel, R.; Dominguez, J.; Lipman, M. Interferon-γ release assays for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Respiratory Journal. 2011-01-01, 37 (1) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 0903-1936. PMID 20847080. doi:10.1183/09031936.00114810. (原始内容存档于2022-10-27) (英语).

- ^ Chen, Jun; Zhang, Renfang; Wang, Jiangrong; Liu, Li; Zheng, Yufang; Shen, Yinzhong; Qi, Tangkai; Lu, Hongzhou. Interferon-Gamma Release Assays for the Diagnosis of Active Tuberculosis in HIV-Infected Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE. 2011-11-01, 6 (11) [2022-12-06]. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3206065 . PMID 22069472. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026827. (原始内容存档于2022-11-10) (英语).

- ^ Diseases, Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical. Diagnostics for tuberculosis : global demand and market potential.. Geneva: World Health Organization on behalf of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. 2006: 36 [2015-01-20]. ISBN 978-92-4-156330-7. (原始内容存档于2014-11-10).

- ^ 82.0 82.1 82.2 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 117: Tuberculosis. London, 2011.

- ^ 83.0 83.1 傳染病介紹 結核病. 卫生福利部疾病管制署. [2016-07-10]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-16).

- ^ Steingart, KR; Flores, LL, Dendukuri, N, Schiller, I, Laal, S, Ramsay, A, Hopewell, PC, Pai, M. Evans, Carlton , 编. Commercial serological tests for the diagnosis of active pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. August 2011, 8 (8): e1001062. PMC 3153457 . PMID 21857806. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001062.

- ^ Rothel J, Andersen P. Diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: is the demise of the Mantoux test imminent?. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005, 3 (6): 981–93. PMID 16307510. doi:10.1586/14787210.3.6.981.

- ^ Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic Review: T-Cell–based Assays for the Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: An Update. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149 (3): 1–9. PMC 2951987 . PMID 18593687. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00241.

- ^ Jindal, editor-in-chief SK. Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2011: 544 [2017-03-03]. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Amicosante, M; Ciccozzi, M; Markova, R. Rational use of immunodiagnostic tools for tuberculosis infection: guidelines and cost effectiveness s tudies. The new microbiologica. April 2010, 33 (2): 93–107. PMID 20518271.

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten; Grossman, David C.; Curry, Susan J.; Bauman, Linda; Davidson, Karina W.; Epling, John W.; García, Francisco A.R.; Herzstein, Jessica; Kemper, Alex R.; Krist, Alex H.; Kurth, Ann E.; Landefeld, C. Seth; Mangione, Carol M.; Phillips, William R.; Phipps, Maureen G.; Pignone, Michael P. Screening for Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Adults. JAMA. 2016-09-06, 316 (9): 962. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.11046.

- ^ 90.0 90.1 Hawgood, Barbara J. Albert Calmette (1863-1933) and Camille Guérin (1872-1961): the C and G of BCG vaccine. Journal of Medical Biography. 2007-08, 15 (3): 139–146 [2021-02-26]. ISSN 0967-7720. PMID 17641786. doi:10.1258/j.jmb.2007.06-15. (原始内容存档于2021-12-24).

- ^ McShane, H. Tuberculosis vaccines: beyond bacille Calmette–Guérin. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2011-10-12, 366 (1579): 2782–9. PMC 3146779 . PMID 21893541. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0097.

- ^ Roy, A; Eisenhut, M; Harris, RJ; Rodrigues, LC; Sridhar, S; Habermann, S; Snell, L; Mangtani, P; Adetifa, I; Lalvani, A; Abubakar, I. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis.. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2014-08-05, 349: g4643. PMC 4122754 . PMID 25097193. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4643.

- ^ Vaccine and Immunizations: TB Vaccine (BCG). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011 [2011-07-26]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-17).

- ^ BCG Vaccine Usage in Canada – Current and Historical. Public Health Agency of Canada. September 2010 [2011-12-30]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-30).

- ^ 95.0 95.1 Teo, SS; Shingadia, DV. Does BCG have a role in tuberculosis control and prevention in the United Kingdom?. Archives of Disease in Childhood. June 2006, 91 (6): 529–31. PMC 2082765 . PMID 16714729. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.085043.

- ^ Van Der Meeren, Olivier; Hatherill, Mark; Nduba, Videlis; Wilkinson, Robert J.; Muyoyeta, Monde; Van Brakel, Elana; Ayles, Helen M.; Henostroza, German; Thienemann, Friedrich. Phase 2b Controlled Trial of M72/AS01E Vaccine to Prevent Tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018-10-25, 379 (17): 1621–1634 [2018-11-03]. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 6151253 . PMID 30280651. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1803484. (原始内容存档于2021-04-15) (英语).

- ^ The Global Plan to Stop TB. World Health Organization. 2011 [2011-06-13]. (原始内容存档于2011-06-12).

- ^ Warrell, ed. by D. J. Weatherall ... [4. + 5. ed.] ed. by David A. Sections 1 – 10. 4. ed., paperback. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. 2005: 560 [2017-03-12]. ISBN 978-0-19-857014-1. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Brennan PJ, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64: 29–63. PMID 7574484. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333.

- ^ Menzies, Dick; Al Jahdali, Hamdan; Al Otaibi, Badriah. Recent developments in treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2011-03, 133: 257–266 [2022-03-26]. ISSN 0971-5916. PMC 3103149 . PMID 21441678. (原始内容存档于2022-07-12).

- ^ Arch G.; III Mainous. Management of Antimicrobials in Infectious Diseases: Impact of Antibiotic Resistance. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. 2010: 69 [2017-03-12]. ISBN 1-60327-238-0. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ 衛生福利部疾病管制署專業人士版. 卫生福利部疾病管制署专业人士版. [2017-03-12]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-02).

- ^ Liu, Qin; Abba, Katharine; Alejandria, Marissa M; Sinclair, David; Balanag, Vincent M; Lansang, Mary Ann D. Reminder systems to improve patient adherence to tuberculosis clinic appointments for diagnosis and treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2014-11-18 [2017-03-12]. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006594.pub3. (原始内容存档于2017-03-12) (英语).

- ^ Karumbi, Jamlick; Garner, Paul. Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group , 编. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015-05-29. PMC 4460720 . PMID 26022367. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003343.pub4 (英语).

- ^ O'Brien, R. J. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: etiology, management and prevention. Seminars in Respiratory Infections. 1994-06, 9 (2) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 0882-0546. PMID 7973169. (原始内容存档于2022-11-11).

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs—worldwide, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006, 55 (11): 301–5 [2006-12-06]. PMID 16557213. (原始内容存档于2020-01-12).

- ^ 107.0 107.1 Maryn McKenna. Totally Resistant TB: Earliest Cases in Italy. Wired. 2012-01-12 [2012-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2012-01-14).

- ^ Migliori, G. B.; Iaco, G. De; Besozzi, G.; Centis, R.; Cirillo, D. M. First tuberculosis cases in Italy resistant to all tested drugs. Weekly releases (1997–2007). 2007-05-17, 12 (20) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 9999-1233. doi:10.2807/esw.12.20.03194-en. (原始内容存档于2022-10-27) (英语).

- ^ 109.0 109.1 Paul Kielstra. Zoe Tabary , 编. Ancient enemy, modern imperative – A time for greater action against tuberculosis. Economist Insights (The Economist Group). 2014-06-30 [2014-08-01]. (原始内容存档于2014-07-31).

- ^ Velayati, Ali Akbar; Masjedi, Mohammad Reza; Farnia, Parissa; Tabarsi, Payam; Ghanavi, Jalladein; ZiaZarifi, Abol Hassan; Hoffner, Sven Eric. Emergence of New Forms of Totally Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Bacilli: Super Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis or Totally Drug-Resistant Strains in Iran. CHEST. 2009-08-01, 136 (2). ISSN 0012-3692. PMID 19349380. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2427 (英语).

- ^ Totally Drug-Resistant TB: a WHO consultation on the diagnostic definition and treatment options (PDF). who.int. World Health Organization. [2016-03-25]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-10-21).

- ^ Provisional CDC Guidelines for the Use and Safety Monitoring of Bedaquiline Fumarate (Sirturo) for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. [2017-03-12]. (原始内容存档于2014-01-04).

- ^ Nunn, Andrew J.; Phillips, Patrick P. J.; Meredith, Sarah K.; Chiang, Chen-Yuan; Conradie, Francesca; Dalai, Doljinsuren; Deun, Armand van; Dat, Phan-Thuong; Lan, Ngoc. A Trial of a Shorter Regimen for Rifampin-Resistant Tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019-03-13 [2019-05-25]. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811867. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08) (英语).

- ^ WHO Disease and injury country estimates. World Health Organization. 2004 [2009-11-11]. (原始内容存档于2009-11-11).

- ^ Lambert M, et al. Recurrence in tuberculosis: relapse or reinfection?. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003, 3 (5): 282–7. PMID 12726976. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00607-8.

- ^ Wang, Jann‐Yuan; Lee, Li‐Na; Lai, Hsin‐Chih; Hsu, Hsiao‐Leng; Liaw, Yuang‐Shuang; Hsueh, Po‐Ren; Yang, Pan‐Chyr. Prediction of the Tuberculosis Reinfection Proportion from the Local Incidence. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007-07-15, 196 (2) [2022-10-27]. ISSN 0022-1899. doi:10.1086/518898. (原始内容存档于2022-11-12) (英语).

- ^ 印發現完全抗藥性肺結核. 中央社即时新闻. 2012-01-08 [2012-01-08]. (原始内容存档于2016-02-15) (中文(繁体)).

- ^ 118.0 118.1 Frith, John. History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health. [2021-02-26]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ 119.0 119.1 119.2 Zürcher, Kathrin; Zwahlen, Marcel; Ballif, Marie; Rieder, Hans L.; Egger, Matthias; Fenner, Lukas. Influenza Pandemics and Tuberculosis Mortality in 1889 and 1918: Analysis of Historical Data from Switzerland. PLoS ONE. 2016-10-05, 11 (10) [2021-02-28]. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5051959 . PMID 27706149. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162575. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Frith, John. History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health. [2021-02-26]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Daniel, Thomas M. The history of tuberculosis. Respiratory Medicine. 2006-11-01, 100 (11). ISSN 0954-6111. PMID 16949809. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.006 (英语).

- ^ 122.0 122.1 122.2 122.3 Barberis, I.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Galluzzo, L.; Martini, M. The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. March 2017, 58 (1): E9–E12 [2021-02-28]. ISSN 1121-2233. PMC 5432783 . PMID 28515626. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ The Next Pandemic - Tuberculosis: The Oldest Disease of Mankind Rising One More Time. British Journal of Medical Practitioners. [2021-02-26]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-28).

- ^ Zürcher, Kathrin; Zwahlen, Marcel; Ballif, Marie; Rieder, Hans L.; Egger, Matthias; Fenner, Lukas. Influenza Pandemics and Tuberculosis Mortality in 1889 and 1918: Analysis of Historical Data from Switzerland. PLoS ONE. 2016-10-05, 11 (10) [2021-02-28]. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5051959 . PMID 27706149. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162575. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ 125.0 125.1 125.2 125.3 Frith, John. History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health. [2021-02-26]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800-1922. Contagion - CURIOSity Digital Collections. 2020-03-26 [2022-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08) (英语).

- ^ 127.0 127.1 Daniel, Thomas M. Captain of death: the story of tuberculosis. Rochester, NY, USA: University of Rochester Press. 1997 [2021-02-28]. ISBN 978-1-878822-96-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ Rubin, S. A. Tuberculosis. Captain of all these men of death. Radiologic Clinics of North America. July 1995, 33 (4): 619–639 [2021-02-28]. ISSN 0033-8389. PMID 7610235. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1905. NobelPrize.org. [2021-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2018-01-17) (美国英语).

- ^ 卡介苗 (PDF). 世界卫生组织. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2022-02-03) (中文).

- ^ 范姜宇龙. 結核話說從頭. 台湾感染管制学会. [2014-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-16) (中文).

- ^ 卫生福利部疾病管制署. 結核病年度流病簡報( 2016-03-23). 卫生福利部疾病管制署. 2016-03-23 [2016-05-01]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-11).

- ^ 133.0 133.1 苏维钧. 肺结核大反扑之自保之道.台北市: 元气斋出版社.2004年3月: 153. ISBN 978-986-759-611-6.

- ^ 都治计划 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)卫生福利部疾病管制署

- ^ 結核病 Q & A. [2022-07-13]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-31).

- ^ 论质计酬试办计划成效初探-以肺结核疾病为例 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)国家图书馆台湾博硕士论文知识加值系统

- ^ 137.0 137.1 Public-Private Partnership Announces Immediate 40 Percent Cost Reduction for Rapid TB Test (pdf). World Health Organization. 2012-08-06 [2014-02-22]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-10-29).

- ^ Lawn, SD; Nicol, MP. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay: development, evaluation and implementation of a new rapid molecular diagnostic for tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance. Future microbiology. September 2011, 6 (9): 1067–82. PMC 3252681 . PMID 21958145. doi:10.2217/fmb.11.84.

- ^ WHO says Cepheid rapid test will transform TB care. Reuters. 2010-12-08 [2014-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2010-12-11).

- ^ STOPTB. The Stop TB Partnership, which operates through a secretariat hosted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland. (PDF). 2013-04-05 [2014-02-22]. (原始内容 (pdf)存档于2014-01-24).

- ^ Lienhardt, C; Espinal, M; Pai, M; Maher, D; Raviglione, MC. What research is needed to stop TB? Introducing the TB Research Movement. PLoS medicine. November 2011, 8 (11): e1001135. PMC 3226454 . PMID 22140369. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001135.

- ^ Mishra, G. Tuberculosis Prescription Practices In Private And Public Sector In India. NJIRM. 2013, 4 (2): 71–78 [2014-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-10).

- ^ Bhargava, Anurag; Pinto, Lancelot; Pai, Madhukar. Mismanagement of tuberculosis in India: Causes, consequences, and the way forward. Hypothesis. 2011-04-18, 9 (1) [2014-02-22]. ISSN 1710-3398. doi:10.5779/hypothesis.v9i1.214. (原始内容存档于2020-01-12).

- ^ Amdekar, Yeshwant. Changes in the management of tuberculosis. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2009-07, 76 (7). ISSN 0019-5456. doi:10.1007/s12098-009-0164-4 (英语).

- ^ 监狱中的结核病向外传播. [2015-06-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-01).

- ^ 遏制结核病这个无法被禁锢于铁窗之内的杀手. [2015-06-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-01).

- ^ 在拘留场所抗击结核病. [2015-06-17]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-08).